ABSTRACT

Nodal is the major effector of left-right axis development. In mice, Nodal forms heterodimers with Gdf1 and is inhibited by Cerl2/Dand5 at the node, and by Lefty1 in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM). Studies in zebrafish have suggested some parallels, but also differences, between left-right patterning in mouse and zebrafish. To address these discrepancies, we generated single and double zebrafish mutants for southpaw (spaw, the Nodal ortholog), dand5 and lefty1, and performed biochemical and activity assays with Spaw and Vg1/Gdf3 (the Gdf1 ortholog). Contrary to previous findings, spaw mutants failed to initiate spaw expression in the LPM, and asymmetric heart looping was absent, similar to mouse Nodal mutants. In blastoderm assays, Vg1 and Spaw were interdependent for target gene induction, and contrary to previous results, formed heterodimers. Loss of Dand5 or Lefty1 caused bilateral spaw expression, similar to mouse mutants, and Lefty1 was replaceable with a uniform Nodal signaling inhibitor. Collectively, these results indicate that Dand5 activity biases Spaw-Vg1 heterodimer activity to the left, Spaw around Kupffer's vesicle induces the expression of spaw in the LPM and global Nodal inhibition maintains the left bias of Spaw activity, demonstrating conservation between zebrafish and mouse mechanisms of left-right patterning.

KEY WORDS: Left-right patterning, Nodal, Southpaw, Cerl2, Dand5, Lefty

Summary: Single and double mutants generated in the zebrafish nodal, lefty1 and cerl2/dand5 genes reveal that the mechanisms of left-right patterning are highly conserved between zebrafish and mouse.

INTRODUCTION

On its surface, the vertebrate body plan appears bilaterally symmetric, but the morphology and positioning of internal organs reveal an underlying left-right asymmetry: the heart jogs to the left, the liver is positioned on the right and the gut undergoes asymmetric rotation. Nodal, a ligand in the TGFβ protein family, is a major regulator of left-right axis establishment (Blum and Ott, 2018; Blum et al., 2014; Grimes and Burdine, 2017). After its role in mesendoderm patterning, Nodal is expressed in the embryonic node and in the left lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) in mouse (Collignon et al., 1996; Lowe et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 1993), zebrafish (Long et al., 2003), chick (Levin et al., 1995; Pagán-Westphal and Tabin, 1998) and Xenopus (Lowe et al., 1996), and it is expressed asymmetrically in Amphioxus (Li et al., 2017), snails (Grande and Patel, 2009; Kuroda et al., 2009), echinoderms (Duboc et al., 2005) and ascidians (Morokuma et al., 2002).

The mechanisms underlying left-right patterning are well understood in mice, but less established in zebrafish, owing to a reliance on morpholino knockdown phenotypes and an absence of null mutants. Knockdown of southpaw (spaw, a zebrafish Nodal ortholog) results in an absence of spaw in the LPM, and subsequent heart jogging and looping phenotypes (Long et al., 2003), similar to Nodal mutant mice (Brennan et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2008; Saijoh et al., 2003). In contrast, spaw mutants with a C-terminal point mutation still initiate (but do not propagate) spaw expression in the LPM, and then develop heart jogging, but not looping, phenotypes (Noël et al., 2013). This has led to the conclusion that heart chirality in zebrafish is controlled by a Nodal-independent mechanism (Noël et al., 2013). However, it is unclear whether the existing spaw allele is a null mutant. Thus, a loss-of-function mutation in spaw is needed to directly test its function in zebrafish left-right patterning, and to determine whether Nodal function is conserved between fish and mouse.

A second TGFβ family member, Gdf1, is also expressed in the node and LPM (Rankin et al., 2000). Nodal-Gdf1 heterodimers pattern the mouse left-right axis (Tanaka et al., 2007). Consistent with Gdf1 mutant phenotypes, knockdown of zebrafish vg1/gdf3 causes a reduction or absence of spaw in the LPM and heart looping phenotypes (Peterson et al., 2013), and rescue experiments of maternal-zygotic vg1 mutants suggest that Spaw requires Vg1 to pattern the left-right axis (Pelliccia et al., 2017). However, in contrast to mouse Nodal-Gdf1, Spaw-Vg1 heterodimers have not been detected in zebrafish (Peterson et al., 2013). Thus, it remains unclear whether the role of Vg1/Gdf1 in left-right patterning is conserved between fish and mouse.

Asymmetric Nodal expression in the mouse LPM is initiated and maintained through two means of inhibition. First, Nodal is inhibited on the right side of the node by Cerl2/Dand5, a member of the Cerberus/Dan family of secreted TGFβ antagonists. Like Cerl2/Dand5 mouse mutants (Marques et al., 2004), dand5/charon zebrafish morphants develop bilateral spaw expression, and heart jogging and looping defects (Hashimoto et al., 2004). Lowering dand5 levels by morpholino knockdown causes premature induction of spaw expression in the LPM, but no change in the rate of propagation was observed (Wang and Yost, 2008). Dand5 mutants have not been reported in zebrafish.

Second, Lefty1 at the midline is thought to restrict Nodal activity to the left. Zebrafish lefty1 morphants (Wang and Yost, 2008) and mutants (Rogers et al., 2017) have defects in heart jogging. lefty1 morphants also develop bilateral spaw expression (Wang and Yost, 2008), and similar to mouse lefty1 mutants (Meno et al., 1998), left LPM spaw expression precedes the right (Wang and Yost, 2008). These data have led to the suggestion that Lefty1 functions as a midline barrier during left-right patterning (Lenhart et al., 2011; Meno et al., 1998; Wang and Yost, 2008), but Lefty1 has also been proposed to act through a self-enhancement and lateral-inhibition (SELI) feedback system (Nakamura et al., 2006). Surprisingly, during mesendoderm patterning in zebrafish, Lefty1 and Lefty2 can be replaced with uniform inhibition via a Nodal inhibitor drug (Rogers et al., 2017). This raises the question of whether (1) lefty1 localization, (2) the timing of lefty1 expression and (3) dynamic feedback between Nodal and lefty1 are required for left-right patterning.

In this study, we assessed to what extent the mechanisms driving left-right patterning are conserved between mouse and zebrafish. We genetically tested the role of the secreted factors spaw, dand5 and lefty1 in zebrafish by generating single and double null mutants. Our results reveal that Spaw is required to transfer spaw expression to the LPM, Dand5 and Lefty1 restrict Spaw to the left side, and Spaw and Vg1 form heterodimers. Additionally, we show that Dand5 and Lefty1 control the timing and speed of Spaw propagation, and that the localization and timing of lefty1 expression are not always crucial for left-right patterning. Collectively, these results clarify and unify the regulatory mechanisms of left-right patterning.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Spaw, Dand5 and Lefty1 are required for left-right asymmetry

To test whether the mechanisms of left-right axis establishment are conserved between mouse and zebrafish, we analyzed single and double mutants for spaw, dand5 and lefty1 (Fig. 1A,B). We used CRISPR-Cas9 to generate frameshifting mutants for dand5 and spaw, and used previously generated lefty1 mutants (Rogers et al., 2017) (Table S1). All six mutant combinations were homozygous viable and lacked gross phenotypes (Fig. 1C) but displayed randomized or symmetric heart looping and jogging (Fig. 1D,E). In particular, spaw mutants displayed randomization of heart jogging, and failed to produce a normal heart loop, contrary to spaw C-terminal point mutants (Noël et al., 2013) but similar to spaw morphants (Long et al., 2003) and mouse Nodal mutants (Brennan et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2008; Saijoh et al., 2003).

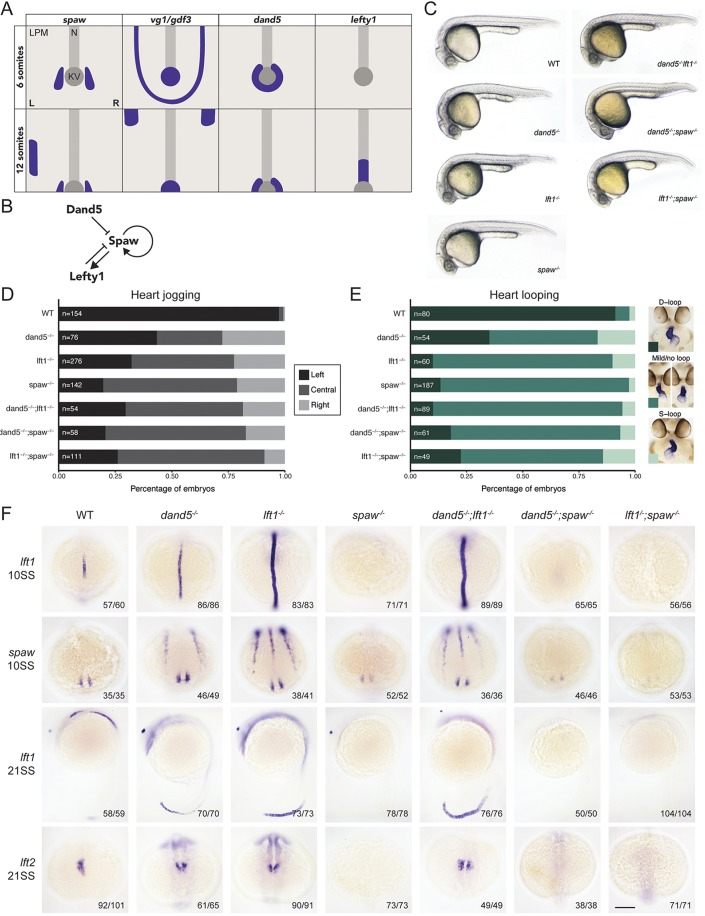

Fig. 1.

Spaw, Dand5 and Lefty1 are required for left-right asymmetry. (A) Expression patterns of spaw, vg1/gdf3, dand5 and lefty1 in wild-type zebrafish embryos. LPM, lateral plate mesoderm; N, notochord; KV, Kupffer's vesicle. (B) Spaw induces itself and its inhibitor Lefty1. Spaw is also inhibited by Dand5. (C) Wild-type (WT), dand5, lefty1 (lft1), spaw, dand5;lft1, dand5;spaw and lft1;spaw embryos at 28 h post-fertilization (hpf). See Table S1 for information about the mutant alleles. (D) Quantification of heart jogging at 28 hpf in wild-type and mutant embryos. (E) Quantification of heart looping at 2 days post-fertilization (dpf) in wild-type and mutant embryos, detected by expression of myl7/cmlc2 by in situ hybridization. D-loop, dextral loop; S-loop, sinistral loop. A large proportion of hearts failed to loop correctly in either direction, forming no loop or a very mild loop. We designated these embryos as ‘mild/no loop’. (F) Expression of lefty1, spaw and lefty2 (lft2) at the 10-somite stage (10SS) and 21SS in wild-type and mutant embryos. Each image is representative of three to five independent experiments (embryo number is in bottom right corner of each panel). Scale bar: 150 µm.

To understand the effect of the mutations on gene expression, we analyzed lefty1, lefty2 and spaw expression during somitogenesis (Fig. 1F). In spaw, dand5;spaw and lefty1;spaw mutants, spaw expression was reduced around Kupffer's vesicle (the zebrafish equivalent to the mouse node in left-right patterning), and lefty1 and lefty2 expression was lost. In dand5, lefty1 and dand5;lefty1 mutants, spaw was expressed in both the left and right LPM, lefty1 expression was higher in the midline, and lefty2 was expressed in both heart fields (Fig. 1F). In addition, in lefty1 and dand5;lefty1 mutants, spaw was expressed in the midline, a phenotype not observed in zebrafish morphants (Wang and Yost, 2008) and only weakly visible in mouse mutants (Meno et al., 1998). However, spaw midline expression is consistent with the endogenous expression of the Nodal co-receptor one-eyed pinhead (oep)/tdgf1 and the Nodal pathway transcription factor foxh1 in the midline (Pogoda et al., 2000; Sirotkin et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 1998). Thus, Spaw is an upstream activator of spaw, lefty1 and lefty2, and Dand5 and Lefty1 restrict the localization of spaw. Collectively, these results reveal that the roles of Nodal, Dand5 and Lefty1 are conserved from mouse to zebrafish.

Spaw and Vg1 form heterodimers

Vg1 is not detectably processed or secreted on its own, but upon co-expression with its heterodimeric Nodal partners cyclops or squint, it is cleaved to its mature form and secreted (Montague and Schier, 2017). To determine whether Spaw and Vg1 also form functional heterodimers like Cyclops-Vg1, Squint-Vg1 and mouse Nodal-Gdf1, we generated superfolderGFP (sfGFP) and epitope-tagged versions of Spaw and Vg1, and tested the activity, processing, interaction and localization of Spaw and Vg1. Expression of vg1-sfGFP in the presence and absence of spaw revealed that, while Spaw-sfGFP alone was cleaved to its mature form and secreted, Vg1-sfGFP was cleaved and secreted only in the presence of Spaw (Fig. 2A-C).

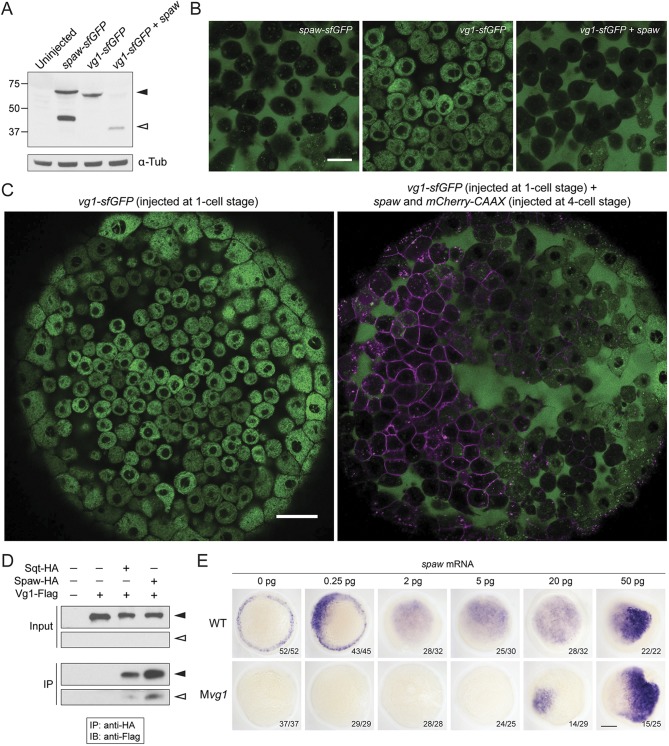

Fig. 2.

Spaw and Vg1/Gdf3 form heterodimers. (A) Anti-GFP reducing immunoblot of wild-type embryos injected with 25 pg of spaw-sfGFP, vg1-sfGFP or vg1-sfGFP and spaw mRNA. Black arrowhead indicates the position of full-length protein; open arrowhead represents cleaved protein. Lower panel: anti-α-Tubulin loading control. (B) Animal cap of sphere-stage live embryos injected at the one-cell stage with 50 pg of spaw-sfGFP, 50 pg of vg1-sfGFP mRNA or 50 pg of vg1-sfGFP and 50 pg of spaw mRNA. Scale bar: 20 µm. (C) Animal cap of a sphere-stage live embryo injected with 50 pg of vg1-sfGFP mRNA at the one-cell stage (left) or 50 pg of vg1-sfGFP mRNA at the one-cell stage and 25 pg of a spaw mRNA/mCherry-CAAX mRNA mix at the four-cell stage (right). Scale bar: 40 µm. (D) Anti-Flag reducing immunoblot (IB) of anti-HA immunoprecipitates (IPs) from lysates of wild-type embryos injected with 50 pg of squint-HA (sqt-HA), 50 pg of spaw-HA and/or 50 pg of vg1-Flag mRNA. Black arrowheads indicate the position of full-length protein; open arrowheads represent cleaved protein. The input and IP blots were exposed for different lengths of time. (E) Expression of lefty1 in wild-type and maternal vg1 (Mvg1) mutant embryos injected with 0.25-50 pg of spaw mRNA. Scale bar: 150 µm.

If Vg1 and Spaw form heterodimers, a biochemical interaction should be detectable. We performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments by co-expressing vg1-Flag with spaw-HA, or squint-HA as a positive control (Montague and Schier, 2017). In contrast to previous studies (Peterson et al., 2013), an interaction was detected between Vg1 and Spaw (Fig. 2D), indicating that Vg1 and Spaw form heterodimers.

To test whether Spaw activity is dependent on Vg1, we expressed Spaw in the presence or absence of Vg1. Expression of 0.25-5 pg of spaw mRNA in blastula embryos induced ectopic Nodal target gene expression in wild-type embryos, but failed to induce ectopic gene expression in maternal vg1 (Mvg1) mutants (Fig. 2E), indicating that Spaw requires Vg1 for full activity. Nodal target gene expression was induced in embryos injected with 20 pg or more of spaw mRNA in the absence of vg1, suggesting that, at high concentrations, Spaw might be able to form active homodimers. Collectively, these results suggest that, after Spaw is translated, it heterodimerizes with inactive, unprocessed Vg1. Vg1-Spaw dimerization facilitates the cleavage and secretion of Vg1, producing a mature active heterodimer.

Dand5 and Lefty1 regulate the timing and speed of spaw propagation

Analysis of spaw expression in the single and double mutants revealed that spaw propagated through the LPM of dand5 and lefty1 mutants before it had initiated LPM expression in wild-type embryos (Fig. 1F). To understand whether this was due to a difference in the onset of spaw expression, the rate of spaw propagation, or both, we analyzed spaw expression (co-stained with the somite marker myod1) across multiple stages of somitogenesis in the single and double mutants. spaw expression never initiated in the LPM of spaw, dand5;spaw or lefty1;spaw mutants (Fig. 3A,B), contrary to previous results (Noël et al., 2013), indicating that Spaw activity is required to initiate spaw expression in the LPM. spaw expression initiated prematurely in the LPM of dand5 and lefty1 mutants, consistent with previous results using morpholino knockdown (Wang and Yost, 2008), and it initiated earliest in dand5;lefty1 mutants (Fig. 3A,B). To understand whether the premature LPM spaw expression was caused by earlier initiation of spaw around Kupffer's vesicle, we analyzed the onset of spaw expression in wild type, dand5, lefty1 and dand5;lefty1 mutants. Indeed, spaw expression was already present around Kupffer's vesicle two to four somite stages (1-2 h) earlier in dand5, lefty1 and dand5;lefty1 mutants than in wild-type embryos (Fig. S1). Thus, Dand5 and Lefty1 both spatially and temporally regulate Spaw activity.

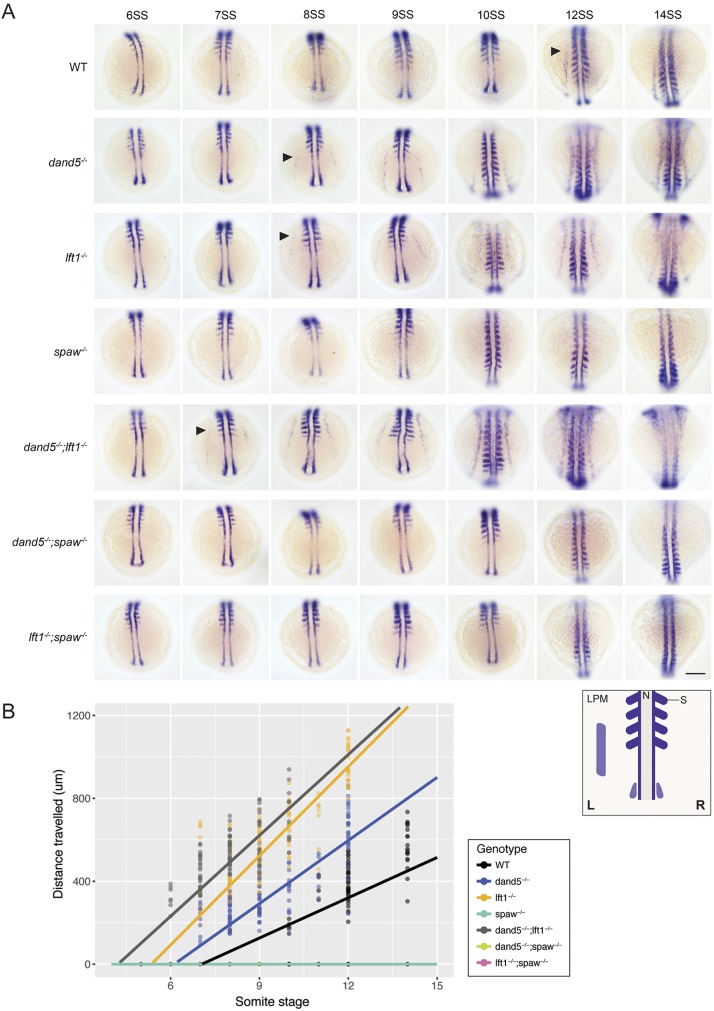

Fig. 3.

Dand5 and Lefty1 regulate the timing and speed of spaw propagation. (A) spaw and myod1 expression in six-somite stage (6SS) to 14SS wild-type and mutant embryos, staged by myod1 somite expression. Black arrowheads represent the earliest stage spaw expression appears in the lateral plate mesoderm. The diagram indicates myod1 expression (dark purple) and spaw expression (light purple). N, notochord, S, somite, LPM, lateral plate mesoderm. Scale bar: 150 µm.(B) Scatterplot of distance spaw has traveled through the LPM in wild-type and mutant embryos. The spaw, dand5;spaw and lefty1;spaw graphs overlap at zero. n=160 (wild type),183 (dand5), 148 (lefty1), 149 (spaw), 115 (dand5;lefty1), 126 (dand5;spaw) and 90 (lefty1;spaw). These values represent the sum of three to six independent experiments. To calculate the rate of spaw propagation, a linear regression was fitted to the data after spaw had initiated in the LPM, see Fig. S2.

To test whether the rate of spaw propagation is affected by the loss of its inhibitors, we measured the distance of spaw expression from the tailbud as a function of somite number (as a proxy for time) in the dand5, lefty1 and dand5;lefty1 mutants. spaw propagated at an approximate rate of 108 µm per somite generation in wild-type embryos and ∼112 µm/somite in dand5 mutants. Contrary to previous morpholino studies (Wang and Yost, 2008), the rate of spaw propagation was slightly higher in lefty1 mutants (∼140 µm/somite) and dand5;lefty1 double mutants (∼125 µm/somite) (Fig. 3B, Fig. S2). Thus, Lefty1 may reduce the speed of Spaw propagation during normal left-right patterning.

Collectively, these results suggest that peri-nodal Spaw induces the expression of spaw in the LPM. Dand5 and Lefty1 inhibit Spaw activity both temporally, which delays the onset of spaw expression, and spatially, which restricts spaw expression to the left LPM. In addition, Lefty1 may reduce the speed at which spaw propagates through the LPM. Although the timing of Nodal propagation in the presence and absence of inhibitors has not been assessed in mouse, the spatial restriction of Nodal by its inhibitors is conserved from fish to mouse.

Uniform Nodal inhibition rescues lefty1 mutants

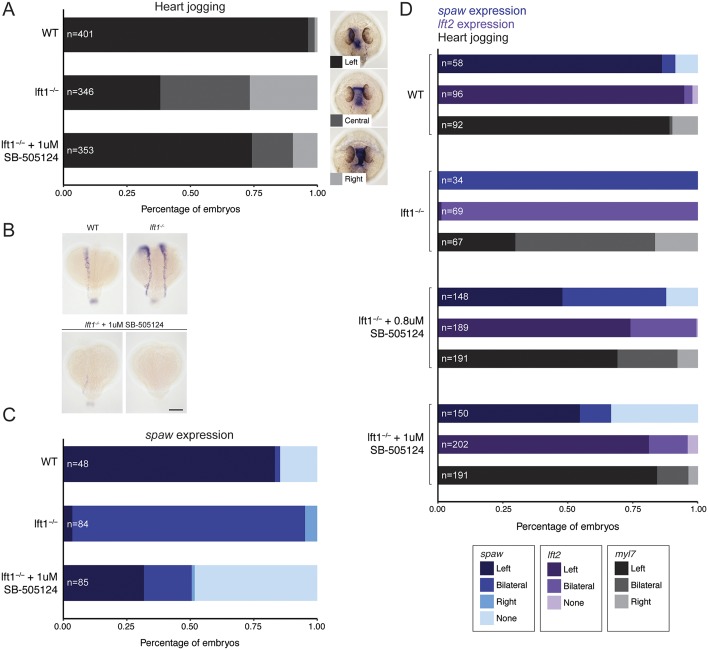

Our results indicate that Lefty1 is required to restrict and/or maintain Spaw activity in the left LPM. To test whether the localization or timing of lefty1 expression is necessary for correct patterning, we replaced lefty1 expression with uniform Nodal inhibition by soaking lefty1 embryos in 1 µM of a Nodal signaling inhibitor drug, SB-505124, from 90% epiboly onwards (prior to the onset of lefty1 expression) (Rogers et al., 2017). Surprisingly, leftward heart jogging was rescued in the majority of drug-treated lefty1 embryos (Fig. 4A,D). Analysis of spaw expression in drug-treated or untreated lefty1 mutants revealed that treatment with SB-505124 was also able to rescue left LPM spaw expression in a subset of embryos (Fig. 4B-D). To dissect why there was a difference between the proportion of embryos with left spaw expression versus left-biased hearts, we analyzed lefty2 expression in the heart field at an intermediate stage between spaw LPM expression and heart positioning at two different concentrations of Nodal inhibitor. lefty2 expression and leftward heart jogging were rescued in a similar proportion of drug-treated lefty1 mutant embryos (Fig. 4D). This suggests that in situ hybridization is not sensitive enough to detect low levels of spaw expression that can lead to asymmetric lefty2 expression, or that leftward heart jogging is not entirely dependent on the presence of an asymmetric Nodal signal.

Fig. 4.

Uniform Nodal inhibition rescues lefty1 mutants. (A) Quantification of heart jogging in wild-type, lefty1 embryos and lefty1 embryos soaked in 1 µM of the Nodal inhibitor SB-505124. (B) Examples of left, bilateral and no spaw expression in wild-type, lefty1 and SB-505124-treated lefty1 mutant embryos. Scale bar: 150 µm.(C) Quantification of spaw expression in wild-type, lefty1 and SB-505124-treated lefty1 mutant embryos. (D) Quantification of spaw expression, lft2 expression and heart jogging in wild-type, lefty1, and 0.8 µM and 1 μM SB-505124-treated lefty1 embryos.

These results reveal that left-right patterning can occur in the absence of timely expression and midline localization of lefty1. In addition, although Lefty1 and Spaw normally function in a feedback system (Fig. 1B), Spaw-Lefty1 feedback can be removed for normal left-right patterning. Thus, lefty1-mediated inhibition may primarily function to dampen Nodal signaling to prevent its amplification and extension to the right LPM.

Conclusions

Our mutant analyses clarify four roles of Spaw and its inhibitors in zebrafish left-right patterning. First, spaw-null mutants show disruptions to both heart jogging and looping, indicating that Spaw is required for proper heart asymmetry. In addition, spaw, spaw;dand5 and spaw;lefty1 mutants fail to initiate spaw expression in the LPM, revealing that Spaw around Kupffer's vesicle is required to transfer spaw expression to the LPM. This is consistent with mouse data: mouse mutants that lack Nodal activity in the node fail to express Nodal in the LPM, and later develop left-right patterning defects, including heart jogging and looping phenotypes (Brennan et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2008; Saijoh et al., 2003). Thus, these results reveal conservation between the roles of zebrafish Spaw and mouse Nodal in left-right patterning.

Second, our results show that in blastoderm assays, Vg1 is required for Spaw activity, Spaw allows the secretion and processing of Vg1, and Spaw and Vg1 interact. These results are consistent with genetic and biochemical data showing Gdf1 is a heterodimeric partner of Nodal during mouse left-right patterning (Tanaka et al., 2007).

Third, mutations in the Nodal inhibitors dand5 and lefty1 result in bilateral spaw expression, demonstrating functional conservation with the mouse orthologs Cerl2/Dand5 and Lefty1, the absence of which leads to bilateral Nodal expression and organ asymmetry defects (Marques et al., 2004; Meno et al., 1998). In addition, our results reveal that the loss of Dand5 and Lefty1 leads to precocious spaw expression, and the loss of Lefty1 leads to accelerated spaw progression, suggesting these inhibitors normally control the timing, speed and localization of Nodal expression.

Fourth, application of a Nodal inhibitor drug to lefty1 mutant embryos is sufficient to rescue normal heart jogging and left-sided expression of spaw in most animals, suggesting that the localization of Lefty1 activity is not always crucial. Rather, Lefty1 dampens Nodal activity to prevent its amplification and extension to the right side of the embryo.

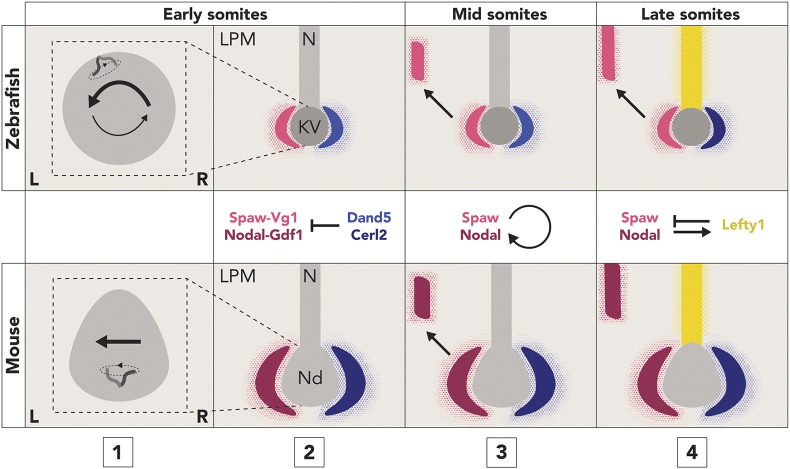

Collectively, our results show that the mechanisms of left-right patterning are highly conserved from mouse to zebrafish and suggest a refined model of zebrafish left-right patterning: (1) rotation of cilia in Kupffer's vesicle causes leftward flow of fluid; (2) Dand5 creates an initial bias in Spaw-Vg1 heterodimer activity at the node; (3) Spaw-Vg1 induces the expression of spaw in the LPM; and (4) Lefty1-mediated inhibition maintains the left-right bias of Spaw activity during auto-induction (Fig. 5). Given that the basic functions of Nodal, Dand5, Lefty and cilia/the left-right organizer are also conserved in Xenopus left-right patterning (Blum et al., 2014; Branford et al., 2000; Schweickert et al., 2010, 2007; Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007), these results suggest that the roles of the Nodal cascade and left-right organizer may be conserved across all vertebrates, with the exception of the sauropsida (Blum and Ott, 2018). These studies lay the foundation for future biochemical and biophysical analyses needed to determine how fluid flow is converted into asymmetric gene expression, and how Nodal pathway components interact to generate precise timing and localization during left-right patterning.

Fig. 5.

Left-right patterning mechanisms are conserved from zebrafish to mouse. (1) Rotation of motile cilia in the left-right organizer (Kupffer's vesicle, zebrafish; node, mouse) causes the leftward flow of fluid that precedes asymmetric gene expression. (2) Spaw-Vg1 and Nodal-Gdf1 heterodimers are restricted to the left by Dand5/Cerl2 activity at the node. (3) Spaw/Nodal induces expression of spaw/Nodal in the left LPM, and (4) Spaw activity is maintained on the left by Lefty1-mediated inhibition. LPM, lateral plate mesoderm; N, notochord; KV, Kupffer's vesicle; Nd, node.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All vertebrate animal work was performed at the facilities of Harvard University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences (HU/FAS). The HU/FAS animal care and use program maintains full AAALAC accreditation, is assured with OLAW (A3593-01) and is currently registered with the USDA. This study was approved by the Harvard University/Faculty of Arts and Sciences Standing Committee on the Use of Animals in Research and Teaching under protocol number 25-08.

Zebrafish husbandry and microinjection

Zebrafish embryos were grown at 28°C and staged according to Kimmel et al. (1995). For somite stages (except drug treatments), embryos were grown at 28°C until sphere stage, and then grown overnight at room temperature. Embryos were cultured in blue water (250 mg/l Instant Ocean salt, 1 mg/l Methylene Blue in reverse osmosis water adjusted to pH 7 with NaHCO3). Embryos for immunoblot and live imaging experiments were chemically dechorionated with 1 mg/ml pronase (protease type XIV from Streptomyces griseus, Sigma) prior to injection, and cultured in agarose-coated dishes. Embryos were injected at the one-cell stage unless otherwise stated.

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of dand5 and spaw

sgRNAs targeting the dand5/charon and spaw genes were designed using CHOPCHOP (Labun et al., 2016; Montague et al., 2014) (Table S1) and synthesized as previously described (Gagnon et al., 2014). TLAB wild-type zebrafish embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with sgRNAs and ∼0.5 nl of 50 µM Cas9 protein. Injected embryos were raised to adulthood and outcrossed to TLAB adults. The resulting clutches were genotyped to identify potential founders with germline mutations in dand5 or spaw by MiSeq sequencing. Animals were recovered with a 4 bp deletion in the first exon of dand5 (dand5a204), causing a frameshift and truncation of Dand5 from 243 amino acids to 54 amino acids, and a 49 bp deletion in the first exon of spaw (spawa205), resulting in a frameshift and truncation of Spaw from 404 amino acids to 49 amino acids (Table S1). The offspring of confirmed founders were raised to adulthood and genotyped by fin-clipping to determine heterozygous individuals. Homozygous animals were generated by intercrossing heterozygous fish.

Generation of double mutants

dand5;lefty1, dand5;spaw and lefty1;spaw mutants were generated by intercrossing homozygous dand5, spaw and lefty1 (Rogers et al., 2017) mutants to generate double heterozygous mutants. Double heterozygous mutants were intercrossed and genotyped to identify double homozygous mutants.

Genotyping of mutants

Genomic DNA was extracted from embryos and fin-clips using the HotSHOT method (Meeker et al., 2007), and PCR was performed using standard methods. spaw and vg1/gdf3 mutants (vg1a165) (Montague and Schier, 2017) were genotyped by gel electrophoresis, dand5 mutants were genotyped by Sanger sequencing, and lefty1 mutants (lefty1a145) were genotyped by PshAI digestion (Rogers et al., 2017). Primer sequences were as follows: dand5_genotype_F, TCACAACAATTGGCGCTTTC; dand5_genotype_R, GCCAAGAACGCGGGAAAC; lefty1_genotype_F, CGTGGCTTTCATGTATCACCTTC; lefty1_genotype_R, GGATGCCGGCCAAACTG; spaw_genotype_F, CGCGTTATTTGTTTTACGCGTTG; spaw_genotype_R, TGCTTACCTTGTGCAATCAAGC; vg1_genotype_F, CTTGCAGATGTGGATTTCTGGCC; and vg1_genotype_R, CATGATGCGATGGTTTGGGTCG.

Cloning of expression and in situ probe constructs

The spaw CDS sequence was PCR amplified from a somite-stage cDNA library and cloned into the pCS2(+) vector using Gibson cloning (Gibson et al., 2009) to generate pCS2(+)-spaw. spaw-sfGFP was generated by inserting the superfolder GFP (sfGFP) sequence (Pédelacq et al., 2006) downstream of the spaw cleavage site (RHKR) in pCS2(+)-spaw with Gibson cloning. mCherry-CAAX was generated by inserting a farnesylation sequence at the 3′ end of the mCherry CDS in a pCS2(+) vector. vg1, vg1-sfGFP, vg1-Flag and sqt-HA have been previously reported (Montague and Schier, 2017). spaw-HA was generated by inserting the HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) sequence downstream of the cleavage site by site-directed mutagenesis of pCS2(+)-spaw. For all fusion constructs, the epitope or sfGFP tag was flanked by a GSTGTT linker at the 5′ end of the tag and by a GS linker at the 3′ end of the tag. In situ probes targeting lefty1, spaw, lefty2, myl7 and myod1 were generated by inserting the full CDS, or up to 1000 bp of the CDS of the gene into the pSC vector using Strataclone (Agilent).

mRNA and probe synthesis

Expression constructs were linearized by digestion with NotI, followed by mRNA synthesis using the SP6 mMessage Machine Kit (ThermoFisher). In situ antisense probes were synthesized using a DIG Probe Synthesis Kit (Roche).

In situ hybridization

Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% formaldehyde, followed by whole-mount in situ hybridization according to standard protocols (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). NBT/BCIP/alkaline phosphatase-stained embryos were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Imager.Z1 after dehydration with methanol and clearing with benzyl benzoate:benzyl alcohol (BBBA).

Morphological analysis of mutant phenotypes and live imaging

Embryos at 24 h post-fertilization (hpf) were anesthetized using Tricaine (Sigma) and imaged in 2% methylcellulose. spaw-sfGFP-injected embryos were mounted at sphere stage in 1% low gelling temperature agarose (Sigma) and live imaged using a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope.

Immunoblotting and co-immunoprecipitation

Embryos were injected with 50 pg of mRNA (unless otherwise stated), and grown until 50% epiboly, then flash frozen (eight embryos per sample) in liquid nitrogen after manual deyolking using forceps. The samples were boiled for 5 min at 95°C with 2× SDS loading buffer and DTT, and then loaded onto Any kD protein gels (Bio-Rad). The samples were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare) before blocking in 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad) in TBST at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-GFP, 1:5000, ThermoFisher A11122; mouse anti-α-Tubulin, 1:5000, ICN Biomedicals 691251; rabbit anti-Flag, 1:2000, Sigma F7425). HRP-coupled secondary antibody was applied to the membranes (goat anti-rabbit, 1:15,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs 111-035-144) and Amersham ECL reagent (GE Healthcare) was used for chemiluminescence detection. For co-immunoprecipitation experiments, 80 embryos per sample were homogenized in 400 µl of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors, Sigma 11836170001) and vortexed every 5 min during a 30-min incubation on ice. Samples were spun at 4°C for 30 min, and then the supernatant was transferred to a tube with 50 µl of anti-HA affinity matrix (Roche 11815016001). Samples were rocked at 4°C overnight. The samples were spun for 2 min and washed in ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors) five times before adding 2×SDS loading buffer and DTT. Immunoblots were performed as above.

Image adjustments

Images were processed in ImageJ/FIJI (Schindelin et al., 2012). Brightness, contrast and color balance were applied uniformly to images.

Drug treatments

Embryos were grown at 28°C until 75% epiboly, then dechorionated using pronase. At 90% epiboly, the embryos were placed in agarose-coated dishes containing pre-warmed Nodal inhibitor SB-505124 (S4696, Sigma) diluted in blue water. After development to 18 somites, 22 somites or 28 hpf at 28°C, the embryos were fixed for in situ hybridization in 4% formaldehyde. SB-505124 was stored at 4°C in a 10 mM stock.

spaw LPM measurements

Embryos were co-stained using a mix of the spaw and myod1 probes. To calculate spaw propagation in the LPM, a measurement was made from the lowest point of myoD staining (base of the notochord) to the highest point of spaw staining on the left side of the embryo. For embryos in which spaw had propagated a substantial distance up the LPM, the embryo was imaged from multiple orientations, and the distances summed. Embryos were also imaged from the side to ensure that the curved surface of the embryo did not affect the final measurement. For spaw propagation calculations, a linear regression line was fit to the scatter plot of spaw distance at time points after initiation of expression in the LPM. This ensured that the timing of spaw propagation did not affect the slope of spaw propagation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Pauli and Nate Lord for helpful comments on the manuscript, Fred Rubino for immunoblot advice, Andrea Pauli for generating the mCherry-CAAX plasmid, and Kathryn Berg and Joo Won Choi for assistance with genotyping.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: T.G.M., A.F.S.; Methodology: T.G.M.; Validation: T.G.M.; Formal analysis: T.G.M.; Investigation: T.G.M.; Resources: J.A.G.; Writing - original draft: T.G.M.; Writing - review & editing: T.G.M., J.A.G., A.F.S.; Visualization: T.G.M.; Supervision: A.F.S.; Project administration: A.F.S.; Funding acquisition: A.F.S.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37GM056211) and a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) Fellowship (T.G.M.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.171090.supplemental

References

- Blum M. and Ott T. (2018). Animal left-right asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 28, R301-R304. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum M., Feistel K., Thumberger T. and Schweickert A. (2014). The evolution and conservation of left-right patterning mechanisms. Development 141, 1603-1613. 10.1242/dev.100560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford W. W., Essner J. J. and Yost H. J. (2000). Regulation of gut and heart left-right asymmetry by context-dependent interactions between xenopus lefty and BMP4 signaling. Dev. Biol. 223, 291-306. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J., Norris D. P. and Robertson E. J. (2002). Nodal activity in the node governs left-right asymmetry. Genes Dev. 16, 2339-2344. 10.1101/gad.1016202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon J., Varlet I. and Robertson E. J. (1996). Relationship between asymmetric nodal expression and the direction of embryonic turning. Nature 381, 155-158. 10.1038/381155a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duboc V., Röttinger E., Lapraz F., Besnardeau L. and Lepage T. (2005). Left-right asymmetry in the sea urchin embryo is regulated by nodal signaling on the right side. Dev. Cell 9, 147-158. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J. A., Valen E., Thyme S. B., Huang P., Ahkmetova L., Pauli A., Montague T. G., Zimmerman S., Richter C. and Schier A. F. (2014). Efficient mutagenesis by Cas9 protein-mediated oligonucleotide insertion and large-scale assessment of single-guide RNAs. PLoS ONE 9, e98186 10.1371/journal.pone.0098186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G., Young L., Chuang R.-Y., Venter J. C., Hutchison C. A. and Smith H. O. (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Meth. 6, 343-345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande C. and Patel N. H. (2009). Nodal signalling is involved in left-right asymmetry in snails. Nature 457, 1007-1011. 10.1038/nature07603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. T. and Burdine R. D. (2017). Left-right patterning: breaking symmetry to asymmetric morphogenesis. Trends Genet. 33, 616-628. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H., Rebagliati M., Ahmad N., Muraoka O., Kurokawa T., Hibi M. and Suzuki T. (2004). The Cerberus/Dan-family protein Charon is a negative regulator of Nodal signaling during left-right patterning in zebrafish. Development 131, 1741-1753. 10.1242/dev.01070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B. and Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253-310. 10.1002/aja.1002030302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Lualdi M., Lewandoski M. and Kuehn M. R. (2008). Broad mesodermal and endodermal deletion of Nodal at postgastrulation stages results solely in left/right axial defects. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3591-3601. 10.1002/dvdy.21665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda R., Endo B., Abe M. and Shimizu M. (2009). Chiral blastomere arrangement dictates zygotic left–right asymmetry pathway in snails. Nature 462, 790-794. 10.1038/nature08597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labun K., Montague T. G., Gagnon J. A., Thyme S. B. and Valen E. (2016). CHOPCHOP v2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W272-W276. 10.1093/nar/gkw398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart K. F., Lin S.-Y., Titus T. A., Postlethwait J. H. and Burdine R. D. (2011). Two additional midline barriers function with midline lefty1 expression to maintain asymmetric Nodal signaling during left-right axis specification in zebrafish. Development 138, 4405-4410. 10.1242/dev.071092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M., Johnson R. L., Sterna C. D., Kuehn M. and Tabin C. (1995). A molecular pathway determining left-right asymmetry in chick embryogenesis. Cell 82, 803-814. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90477-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Liu X., Xing C., Zhang H., Shimeld S. M. and Wang Y. (2017). Cerberus-Nodal-Lefty-Pitx signaling cascade controls left-right asymmetry in amphioxus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 3684-3689. 10.1073/pnas.1620519114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S., Ahmad N. and Rebagliati M. (2003). The zebrafish nodal-related gene southpaw is required for visceral and diencephalic left-right asymmetry. Development 130, 2303-2316. 10.1242/dev.00436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe L. A., Supp D. M., Sampath K., Yokoyama T., Wright C. V. E., Potter S. S., Overbeek P. and Kuehn M. R. (1996). Conserved left–right asymmetry of nodal expression and alterations in murine situs inversus. Nature 381, 158-161. 10.1038/381158a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques S., Borges A. C., Silva A. C., Freitas S., Cordenonsi M. and Belo J. A. (2004). The activity of the Nodal antagonist Cerl-2 in the mouse node is required for correct L/R body axis. Genes Dev. 18, 2342-2347. 10.1101/gad.306504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker N. D., Hutchinson S. A., Ho L. and Trede N. S. (2007). Method for isolation of PCR-ready genomic DNA from zebrafish tissues. BioTechniques 43, 610-614. 10.2144/000112619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meno C., Shimono A., Saijoh Y., Yashiro K., Mochida K., Ohishi S., Noji S., Kondoh H. and Hamada H. (1998). lefty-1 is required for left-right determination as a regulator of lefty-2 and nodal. Cell 94, 287-297. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81472-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague T. G. and Schier A. F. (2017). Vg1-Nodal heterodimers are the endogenous inducers of mesendoderm. Elife 6, 178 10.7554/eLife.28183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague T. G., Cruz J. M., Gagnon J. A., Church G. M. and Valen E. (2014). CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W401-W407. 10.1093/nar/gku410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morokuma J., Ueno M., Kawanishi H., Saiga H. and Nishida H. (2002). HrNodal, the ascidian nodal-related gene, is expressed in the left side of the epidermis, and lies upstream of HrPitx. Dev. Genes Evol. 212, 439-446. 10.1007/s00427-002-0242-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Mine N., Nakaguchi E., Mochizuki A., Yamamoto M., Yashiro K., Meno C. and Hamada H. (2006). Generation of robust left-right asymmetry in the mouse embryo requires a self-enhancement and lateral-inhibition system. Dev. Cell 11, 495-504. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël E. S., Verhoeven M., Lagendijk A. K., Tessadori F., Smith K., Choorapoikayil S., den Hertog J. and Bakkers J. (2013). A Nodal-independent and tissue-intrinsic mechanism controls heart-looping chirality. Nat. Commun. 4, 2754 10.1038/ncomms3754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagán-Westphal S. M. and Tabin C. J. (1998). The transfer of left-right positional information during chick embryogenesis. Cell 93, 25-35. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pédelacq J.-D., Cabantous S., Tran T., Terwilliger T. C. and Waldo G. S. (2006). Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 79-88. 10.1038/nbt1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelliccia J. L., Jindal G. A. and Burdine R. D. (2017). Gdf3 is required for robust Nodal signaling during germ layer formation and left-right patterning. Elife 6, e28635 10.7554/eLife.28635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A. G., Wang X. and Yost H. J. (2013). Dvr1 transfers left-right asymmetric signals from Kupffer's vesicle to lateral plate mesoderm in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 382, 198-208. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogoda H.-M., Solnica-Krezel L., Driever W. and Meyer D. (2000). The zebrafish forkhead transcription factor FoxH1/Fast1 is a modulator of Nodal signaling required for organizer formation. Curr. Biol. 10, 1041-1049. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00669-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin C. T., Bunton T., Lawler A. M. and Lee S. J. (2000). Regulation of left-right patterning in mice by growth/differentiation factor-1. Nat. Genet. 24, 262-265. 10.1038/73472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K. W., Lord N. D., Gagnon J. A., Pauli A., Zimmerman S., Aksel D. C., Reyon D., Tsai S. Q., Joung J. K. and Schier A. F. (2017). Nodal patterning without Lefty inhibitory feedback is functional but fragile. Elife 6, e28785 10.7554/eLife.28785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijoh Y., Oki S., Ohishi S. and Hamada H. (2003). Left-right patterning of the mouse lateral plate requires nodal produced in the node. Dev. Biol. 256, 160-172. 10.1016/S0012-1606(02)00121-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B. et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Meth. 9, 676-682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert A., Weber T., Beyer T., Vick P., Bogusch S., Feistel K. and Blum M. (2007). Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 17, 60-66. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert A., Vick P., Getwan M., Weber T., Schneider I., Eberhardt M., Beyer T., Pachur A. and Blum M. (2010). The nodal inhibitor Coco is a critical target of leftward flow in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 20, 738-743. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotkin H. I., Gates M. A., Kelly P. D., Schier A. F. and Talbot W. S. (2000). Fast1 is required for the development of dorsal axial structures in zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 10, 1051-1054. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00679-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C., Sakuma R., Nakamura T., Hamada H. and Saijoh Y. (2007). Long-range action of Nodal requires interaction with GDF1. Genes Dev. 21, 3272-3282. 10.1101/gad.1623907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C. and Thisse B. (2008). High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 3, 59-69. 10.1038/nprot.2007.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonica A. and Brivanlou A. H. (2007). The left-right axis is regulated by the interplay of Coco, Xnr1 and derrière in Xenopus embryos. Dev. Biol. 303, 281-294. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. and Yost H. J. (2008). Initiation and propagation of posterior to anterior (PA) waves in zebrafish left-right development. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3640-3647. 10.1002/dvdy.21771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Talbot W. S. and Schier A. F. (1998). positional cloning identifies zebrafish one-eyed pinhead as a permissive EGF-related ligand required during gastrulation. Cell 92, 241-251. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80918-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Sasaki H., Lowe L., Hogan B. L. M. and Kuehn M. R. (1993). Nodal is a novel TGF-beta-like gene expressed in the mouse node during gastrulation. Nature 361, 543-547. 10.1038/361543a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.