Abstract

Objective:

There is a general perception on college campuses that alcohol use is normative. However, nondrinking students account for 40% of the U.S. college population. With much of the literature focusing on intervening among drinkers, there has been less of a focus on understanding the nondrinker college experience. The current study has two aims: to describe the social network differences between nondrinkers and drinkers in a college setting, and to assess perceived social exclusion among nondrinkers.

Method:

First-year U.S. college students (n = 1,342; 55.3% female; 47.7% non-Hispanic White) were participants in a larger study examining a social network of one college class and network associations with alcohol use. Alcohol use, sociocentric and egocentric network ties were assessed, as were experiences of social exclusion related to nondrinking.

Results:

Drinking homophily based on past-month use was found; students tended to associate with others with a similar drinking status. Compared with drinkers, nondrinkers received fewer network nominations within the first-year network and made more nominations outside the first-year network. Nondrinkers’ perceived social exclusion was positively related to the number of drinkers in their social networks, such that those with more drinkers in their network reported more social exclusion.

Conclusions:

College students’ past-month drinking status in the first semester of college is related to their network position and perception of social exclusion. Nondrinking students who are part of a nondrinking community are less likely to feel socially excluded. Improving our understanding of the nondrinker college experience should improve support services for these students.

Despite efforts to quell college student alcohol misuse, it remains a public health concern, with nearly 35% of U.S. college students reporting a heavy drinking occasion in the past month (Schulenberg et al., 2017). This level of hazardous drinking is associated with a multitude of negative consequences, including sexual assaults, injuries, and mortality (White & Hingson, 2013). Understandably, this has led much of the extant college student research to focus on identifying risk and protective factors for alcohol use, and consequently, to develop interventions to reduce alcohol-related harms on campus (Carey et al., 2007).

Less research has been conducted with nondrinking college students. Nationwide surveys indicate that approximately 40% of college student populations have not drunk in the past 30 days (Schulenberg et al., 2017; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015), and nearly 23% of college students report no lifetime use of alcohol (American College Health Association, 2017). Research that examines factors associated with not drinking during college is limited, but it is crucial to understand the experience of nondrinkers in college because heavy drinking cultures may alienate nondrinkers, negatively affect their social experiences, and put them at risk for becoming hazardous drinkers themselves.

The limited literature, to date, has compared college student nondrinkers with drinkers on sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., nondrinkers are more likely to be female and over 21) (Huang et al., 2009) and described self-reported reasons for not consuming alcohol among college student drinkers and nondrinkers (Huang et al., 2011). For nondrinkers, reasons tend to be related to values or lifestyle, such as wanting to avoid a drinker “image,” not wanting to lose selfcontrol or act inappropriately, and religious beliefs. Reasons for not drinking reported by drinkers tend to be more situational in nature, such as needing to drive, interference with school work, or to avoid weight gain (Huang et al., 2011). Disapproval/lack of interest was the most relevant subscale of Johnson and Cohen’s (2004) reasons for not drinking scale when predicting college students’ abstinence over a 6-month period (Rinker & Neighbors, 2013). Other research has investigated the social consequences of abstaining from alcohol use in college. Most notably, Conroy and de Visser (2016) found that college students rate nondrinkers as less sociable than students who drink. This research highlights important beliefs college students hold about the role of alcohol as a social facilitator and is consistent with research showing that social factors are one of the strongest motives for college student drinking (Borsari & Carey, 2001).

As adolescents transition from high school to college, peers are confronted with the possibility of new friendships, often resulting in the expansion of social networks (Wrzus et al., 2013). Social network theory and analysis provide a useful approach to studying social factors for drinking alcohol (or not) in college (Barnett et al., 2014; DeMartini et al., 2013; Mason et al., 2014; Rinker et al., 2016). A recent review of college social network studies found support for relationships between students’ substance use and network characteristics (Rinker et al., 2016). For example, increased alcohol use was associated with a higher likelihood of sharing a tie (e.g., a relationship between two people) with other alcohol users, holding a central position (e.g., greater popularity) in the network (based on friendship nominations), having more reciprocated ties (i.e., friendship nomination agreement), and being in a more tightly interconnected network (typically measured by network density) (Rinker et al., 2016). Although recent research has contributed to the understanding of social network factors associated with college student drinking, it has not specifically examined the social networks of those who report no recent alcohol use. Developing a better understanding of nondrinking college students’ social networks may inform existing alcohol interventions and supports for nondrinking students.

Present study

The aims of the present study were to (a) compare the social network characteristics of nondrinkers and drinkers and (b) explore perceived social consequences and experiences reported by nondrinkers. We expected the following:

Nondrinkers will have lower indegree, a measure of network prominence, defined as the number of friendship nominations a participant receives. Indegree is a common indicator of popularity (Valente, 2010), which has been associated with more drinking among adolescents (Balsa et al., 2011).

Nondrinkers and drinkers will have a significantly higher proportion of their ties matching their own drinking status based on previous work that has found drinking homophily among college students (Barnett et al., 2014; Christakis & Fowler, 2008; Rosenquist et al., 2010).

We also had three exploratory aims:

to determine if nondrinkers and drinkers differ in their number of social ties to (a) other students in the first-year class and (b) ties to individuals outside of the first-year class,

to investigate nondrinkers’ perceived social exclusion and whether nondrinkers’ perceived social exclusion differs depending on their proportion of ties to other nondrinking students,

to determine if living in substance-free housing is associated with less perceived social exclusion among nondrinking students.

Method

Participants

Participants were first-year college students enrolled at a mid-sized, private university in the northeastern United States. First-year students living in exclusively first-year dormitories on campus were eligible to participate (N = 1,660). Of these, 1,342 students (81% of the first-year class; 55.3% female; 47.7% non-Hispanic White) enrolled in the study and completed the baseline survey.1,2 One participant was excluded from the sample because they did not provide drinking data, leaving an analytic sample of 1,341.

Procedures

Study enrollment began in August 2016 and continued through the end of the baseline survey (end of October 2016). Recruitment efforts consisted of advertisements sent to home addresses and campus mailboxes, via email, and in-person at campus events. All students 18 or older provided either written or online consent; students under age 18 provided assent before receiving parental consent. Students were sent an individualized link to the baseline survey to their campus email 6 weeks into the start of the fall semester and were given 2 weeks to complete the survey. All students completed the survey during this 2-week period regardless of their date of enrollment. Participants who completed the survey received a $50 Amazon gift card.

Measures

Demographic information.

Participants reported their birth sex, race, ethnicity, athlete status, and first generation status. Other information was provided by the university before study enrollment, including dormitory assignment, and whether the student lived on a floor designated as substance free. Fraternity or sorority membership status was not collected because first-year students at this university are not permitted to join a fraternity or sorority.

Alcohol use.

Participants were presented with the following question: “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one alcoholic beverage?” and given a definition of a standard drink as “12 oz. of beer, 5 oz. of wine, or 1 oz. shot of liquor.” Participants who indicated one or more drinking days were considered drinkers; participants who indicated zero drinking days were considered nondrinkers.

Network characteristics.

Relational ties to other students within the first-year class (sociocentric network) were obtained by asking participants to select up to 10 other first-year students who were important to them in the past month, from a drop-down list of all eligible students in the first-year class who did not opt out of the network list (n = 1,618). Participants were also asked to provide names of up to 10 important people outside of the first-year class (egocentric network). Participants were asked to describe each of these egocentric ties as a same-university student (but not a first-year), a peer not at the same university (e.g., friend, significant other, sibling), parent, or other. Participants then completed items estimating the alcohol use of each network member. Using the sociocentric network data, we calculated the number of network members selected by each participant (outdegree/outties), the number of selections each participant received (indegree/inties), and the number of ties that were reciprocated divided by the total number of ties regardless of tie direction (mutuality). We also calculated the proportion of each participant’s network ties who were self-reported drinkers (in the sociocentric network) and the proportion that were perceived to be drinkers by the participant (sociocentric and egocentric). The proportion of self-reported drinkers in the sociocentric network was calculated by dividing the number of network members who self-reported drinking in the past 30 days by the total number of nominations.3

Nondrinker social experience scale.

We developed three items to assess how nondrinkers believe they are perceived by others, and to measure the extent to which they feel socially excluded as a result of being a nondrinker. Items were as follows: (a) “To what extent do you feel that not drinking affects how you are perceived by others at your university?” (b) “To what extent do you feel that you are not invited or that you are excluded from social events because others identify you as a nondrinker?” and (c) “To what extent do you feel ‘left out’ in social situations in which others around you are drinking, but you are not?” Response options were not at all, a little, somewhat, and very much, with the additional response option of not applicable for the final item. The three items were combined into a nondrinker social exclusion scale, with higher scores indicating a greater feeling of exclusion (α = .84).

Data analysis

Demographic differences between drinkers and nondrinkers were conducted using t tests and chi-square tests. To test differences in sociocentric and egocentric network characteristics between drinkers and nondrinkers, t tests, network autocorrelation models that use z scores, or chi-square tests were conducted, depending on the nature of the variable. Network autocorrelation models take into account the nonindependence of network data and are described in detail elsewhere (DiGuiseppi et al., 2018; Kenney et al., 2018; Meisel et al., 2018; Ord, 1975). Race, athlete status, firstgeneration status, and substance-free status were controlled for in all network comparisons. The associations between nondrinkers’ perceived social exclusion and peer drinking status were conducted using bivariate correlations. Analyses were conducted in SPSS and R.

Results

Demographic differences

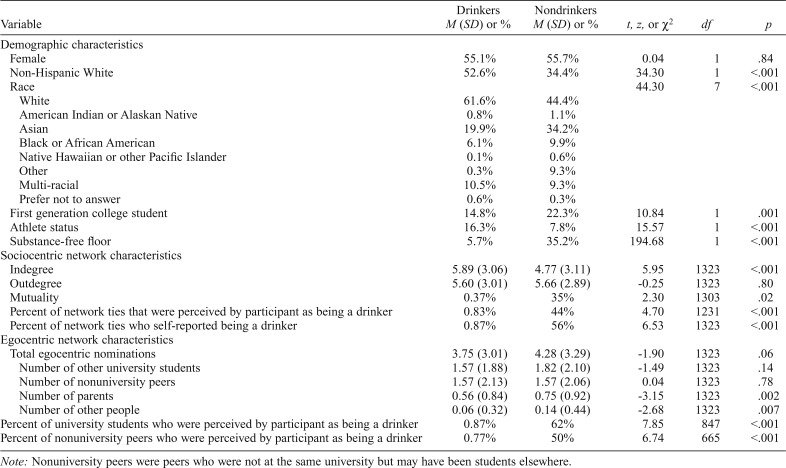

As shown in Table 1, nondrinkers were significantly more likely to be first-generation students and to live on a substance-free dormitory floor compared with drinkers. Nondrinkers were also significantly less likely to identify as non-Hispanic White and to be athletes.

Table 1.

Demographic, sociocentric, and egocentric network differences between drinkers and nondrinkers

| Variable | Drinkers M (SD) or % | Nondrinkers M (SD) or % | t, z, or χ2 | df | p |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Female | 55.1% | 55.7% | 0.04 | 1 | .84 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 52.6% | 34.4% | 34.30 | 1 | <.001 |

| Race | 44.30 | 7 | <.001 | ||

| White | 61.6% | 44.4% | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0.8% | 1.1% | |||

| Asian | 19.9% | 34.2% | |||

| Black or African American | 6.1% | 9.9% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.6% | |||

| Other | 0.3% | 9.3% | |||

| Multi-racial | 10.5% | 9.3% | |||

| Prefer not to answer | 0.6% | 0.3% | |||

| First generation college student | 14.8% | 22.3% | 10.84 | 1 | .001 |

| Athlete status | 16.3% | 7.8% | 15.57 | 1 | <.001 |

| Substance-free floor | 5.7% | 35.2% | 194.68 | 1 | <.001 |

| Sociocentric network characteristics | |||||

| Indegree | 5.89 (3.06) | 4.77 (3.11) | 5.95 | 1323 | <.001 |

| Outdegree | 5.60 (3.01) | 5.66 (2.89) | -0.25 | 1323 | .80 |

| Mutuality | 0.37% | 35% | 2.30 | 1303 | .02 |

| Percent of network ties that were perceived by participant as being a drinker | 0.83% | 44% | 4.70 | 1231 | <.001 |

| Percent of network ties who self-reported being a drinker | 0.87% | 56% | 6.53 | 1323 | <.001 |

| Egocentric network characteristics | |||||

| Total egocentric nominations | 3.75 (3.01) | 4.28 (3.29) | -1.90 | 1323 | .06 |

| Number of other university students | 1.57 (1.88) | 1.82 (2.10) | -1.49 | 1323 | .14 |

| Number of nonuniversity peers | 1.57 (2.13) | 1.57 (2.06) | 0.04 | 1323 | .78 |

| Number of parents | 0.56 (0.84) | 0.75 (0.92) | -3.15 | 1323 | .002 |

| Number of other people | 0.06 (0.32) | 0.14 (0.44) | -2.68 | 1323 | .007 |

| Percent of university students who were perceived by participant as being a drinker | 0.87% | 62% | 7.85 | 847 | <.001 |

| Percent of nonuniversity peers who were perceived by participant as being a drinker | 0.77% | 50% | 6.74 | 665 | <.001 |

Note: Nonuniversity peers were peers who were not at the same university but may have been students elsewhere.

Sociocentric network differences

As shown in Table 1, after we controlled for demographics and substance-free dorm status, there were significant differences in the sociocentric network characteristics of drinkers and nondrinkers. Compared with drinkers, nondrinkers had a significantly lower indegree, suggesting lower network centrality (i.e., popularity) within the first-year student network. Outdegree did not differ between groups, but nondrinkers had a significantly lower mutuality, indicating lower relationship agreement among nondrinkers’ ties. Using participant perceptions of the drinking among their network ties, nondrinkers perceived that the majority of their social network comprised other nondrinkers, and drinkers perceived that the majority of their social network comprised drinkers.

Egocentric network differences

As shown in Table 1, nondrinkers enumerated more network members in their egocentric network (i.e., the network outside of the first-year university class), but this effect was not significant. There were no differences in the number of other same-university students and the number of peers identified outside of the university. However, nondrinkers named more parents and other people. Drinkers also perceived that a higher proportion of the other university students and nonuniversity peers they named were drinkers.

Nondrinkers’perceived social exclusion and peer drinking status

Nondrinkers reported more social exclusion when their network consisted of more self-reported drinkers, r(324) = .13, p < .05, and when they perceived that a higher proportion of their friends were drinkers, r(324) = .19, p < .001. Nondrinkers who lived on substance-free floors reported less social exclusion than nondrinkers who did not, z(320) = -2.63, p < .01. Furthermore, nondrinkers who lived on a substance-free floor perceived that a higher proportion of their friends were also nondrinkers, z(320) = 4.78, p < .001, and had a higher proportion of friends who self-reported being a nondrinker, z(320) = 6.24, p < .001, compared with nondrinkers who did not live in substance-free housing.

Discussion

The current study addresses the paucity of literature on the social experiences of college students who did not consume alcohol in the past month. As expected, nondrinkers occupied less-central positions in the first-year college student network, as evidenced by significantly lower indegree and fewer reciprocated ties compared with drinkers. This aligns with previous findings from social network studies (Rinker et al., 2016), and with students’ perceptions of nondrinkers as less popular than drinkers (Alexander et al., 2001; Ennett et al., 2006). A high prevalence of drinking during the first semester may lead nondrinkers to disengage from other first-year students and seek connections with students outside of their class. Nondrinkers were also more likely to report parents within their ego network, which is consistent with research findings that parental connections and involvement are protective factors against drinking (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; Meisel & Barnett, 2017; Walls et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2004). Although there were no differences between drinkers and nondrinkers in the numbers of non–first-year university students and peers outside of their university, nondrinkers were more likely to name people in the “other” category. Future research with nondrinkers should examine who these people are. Last, consistent with previous research (Barnett et al., 2014; Christakis & Fowler, 2008; Rosenquist et al., 2010), homophily based on drinking status was found among these first-year students, such that nondrinkers affiliated with a higher proportion of other nondrinkers, whereas drinkers affiliated with a higher proportion of drinkers.

We created a questionnaire of items specifically intended to measure perceived social exclusion experienced by nondrinkers. As expected, nondrinkers with a higher proportion of drinking ties reported feeling more socially excluded than nondrinkers with a lower proportion of drinking ties. Living in substance-free housing appeared to have a protective effect, such that nondrinking students living on a substancefree floor perceived less social exclusion than those living in non–substance-free housing. Providing a living environment where nondrinking students feel supported by peers in their choices not to drink may make their college experience more socially satisfying.

Limitations

These analyses relied on cross-sectional data, so we cannot make inferences about causality or how relationships may change over time. Future research should examine whether social exclusion based on nondrinking status is related to alcohol risk longitudinally. Although a large proportion of the first-year college student network (81%) was assessed, missing network members could have changed the characteristics of the observed network and the results. The timeframe used to assess alcohol use was relatively short, in that we asked participants about their drinking only in the past 30 days, which is in line with previous assessments of college student alcohol use (Johnson et al., 2014; Schulenberg et al., 2017). Because of this, this study does not capture drinking that may have occurred in the first 2 weeks of college. We developed the measure of social exclusion administered to nondrinking students; future work may benefit from additional validation of this measure. Last, the sample comprised students enrolled at a mid-sized, private university in the northeastern United States, and as such, the results may not generalize to other college samples.

Implications and future directions

By obtaining a better understanding of experiences unique to nondrinkers, professionals charged with promoting the health of college students can enact more informed prevention efforts and implement programs on college campuses that support the needs of nondrinkers. Our research suggests that nondrinking students who are part of a nondrinking community are less likely to feel socially excluded. Therefore, such programs could demonstrate to students that it is possible to be socially integrated into college life without having to become a drinker to “fit in.” Specifically, universities could offer more substance-free housing options and advertise these options to incoming students more effectively. Future work could further examine the impact that substance-free housing may have on drinkers (i.e., living in substance-free housing may be a protective factor against high-risk drinking even among those who do drink).

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant Nos. R01AA023522, K01AA025994, and T32AA007459-32.

All eligible participants in the first-year class who did not opt out of the network list had their first and last name displayed in the drop-down menu provided within the network survey. No other information about these students was displayed. During the consent process, all eligible students were notified that their name would appear in this drop-down list unless they opted out; n = 42 students decided to opt out at this time.

Using data from the university registrar, it was determined that students who were eligible to participate but did not enroll were significantly more likely to be male, χ2(1) = 7.91, p = .005; non-Hispanic, χ2(1) = 5.43, p = .02; and White, χ2(1) =5.13, p = .02, but were no more likely to live on a substance-free floor compared to those who enrolled.

Only network members who also participated in the study were included.

References

- Abar C., Turrisi R. How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens’ alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.010. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C., Piazza M., Mekos D., Valente T. July). Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00210-5. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. Hanover, MD: Author; 2017. American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment II: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Fall 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa A. I., Homer J. F., French M. T., Norton E. C. Alcohol use and popularity: Social payoffs from conforming to peers’ behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett N. P., Ott M. Q., Rogers M. L., Loxley M., Linkletter C., Clark M. A. Peer associations for substance use and exercise in a college student social network. Health Psychology. 2014;33:1134–1142. doi: 10.1037/a0034687. doi:10.1037/a0034687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Carey K. B. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey K. B., Scott-Sheldon L. A. J., Carey M. P., DeMartini K. S. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Fowler J. H. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy D., de Visser R. Understanding the association between relative sociability prototypes and university students’ drinking intention. Substance Use & Misuse. 2016;51:1831–1837. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1197939. doi:10.1080/10826084 .2016.1197939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini K. S., Prince M. A., Carey K. B. Identification of trajectories of social network composition change and the relationship to alcohol consumption and norms. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.020. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGuiseppi G. T., Meisel M. K., Balestrieri S. G., Ott M. Q., Cox M. J., Clark M. A., Barnett N. P. Resistance to peer influence moderates the relationship between perceived (but not actual) peer norms and binge drinking in a college student social network. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;80:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.020. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett S. T., Bauman K. E., Hussong A., Faris R., Foshee V. A., Cai L., DuRant R. H. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:159–186. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. H., DeJong W., Schneider S. K., Towvim L. G. Endorsed reasons for not drinking alcohol: A comparison of college student drinkers and abstainers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34:64–73. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9272-x. doi:10.1007/s10865-010-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. H., DeJong W., Towvim L. G., Schneider S. K. Sociodemographic and psychobehavioral characteristics of US college students who abstain from alcohol. Journal of American College Health. 2009;57:395–410. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.4.395-410. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.4.395-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. B., Hayes L. D., Brown K., Hoo E. C., Ethier K. A. Vol. 63. MMWR Surveillance Summaries; 2014. October 31). CDC National Health Report: Leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013. No. SS-4, 3–27. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/ mmwrhtml/su6304a2.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. J., Cohen E. A. College students’ reasons for not drinking and not playing drinking games. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1137–1160. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038033. doi:10.1081/JA-120038033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney S. R., DiGuiseppi G. T., Meisel M. K., Balestrieri S. G., Barnett N. P. Poor mental health, peer drinking norms, and alcohol risk in a social network of first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;84:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.04.012. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. J., Zaharakis N., Benotsch E. G. Social networks, substance use, and mental health in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62:470–477. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.923428. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.923428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel M. K., Barnett N. P. Protective and risky social network factors for drinking during the transition from high school to college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:922–929. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.922. doi:10.15288/ jsad.2017.78.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel M. K., DiBello A. M., Balestrieri S. G., Ott M. Q., DiGuiseppi G. T., Clark M. A., Barnett N. P. An event- and network-level analysis of college students’ maximum drinking day. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;79:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.030. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ord K. Estimation methods for models of spatial interaction. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1975;70:120–126. doi:10.1080/ 01621459.1975.10480272. [Google Scholar]

- Rinker D. V., Krieger H., Neighbors C. Social network factors and addictive behaviors among college students. Current Addiction Reports. 2016;3:356–367. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0126-7. doi:10.1007/s40429-016-0126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker D. V., Neighbors C. Reasons for not drinking and perceived injunctive norms as predictors of alcohol abstinence among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2261–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.011. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist J. N., Murabito J., Fowler J. H., Christakis N. A. The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;152:426–433. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00007. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J. E., Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Miech R. A., Patrick M. E. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19-55. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/ monographs/mtf-vol2_2016.pdf.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/ NSDUH-DetTabs2014/NSDUH-DetTabs2014.pdf. [PubMed]

- Valente T. W. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. Social networks and health: Models, methods, and applications (Vol. 1) [Google Scholar]

- Walls T. A., Fairlie A. M., Wood M. D. Parents do matter: A longitudinal two-part mixed model of early college alcohol participation and intensity. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:908–918. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.908. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A., Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2013;35:201–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M. D., Read J. P., Mitchell R. E., Brand N. H. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus C., Hänel M., Wagner J., Neyer F. J. Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:53–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028601. doi:10.1037/a0028601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]