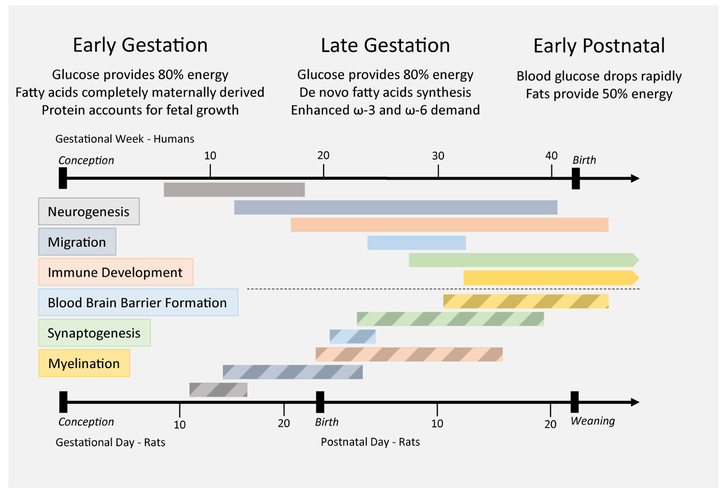

Figure 2. Neurodevelopmental Ontogeny and Nutrient Requirements.

Nutritional requirements for developing offspring change in accordance with physiological demand. During in utero development, glucose provided by circulating maternal glucose is the main source of energy for the developing fetus. Availability of energy and amino acids determine the rate of protein synthesis, and protein accretion is critical to sustaining fetal growth in early and late gestation. During advanced gestation demands for omega-3 (ω-3) and omega-6 (ω-6) essential fatty acids increase, and the fetus is capable of some de novo fatty acid synthesis to assist in lipid accumulation. Immediately following birth, blood glucose drops rapidly as the continual source of maternal glucose via the placenta is replaced with nutrition provided by nursing. Lipids account for a substantial source of energy in the early postnatal stage as fat accumulation continues. The importance of these nutritional changes across development is conserved across animal models, however the timing varies according to developmental rate. Presented are paired neurodevelopmental timelines for humans (above, in gestational weeks post-conception; solid bars) and rats (below, in gestational days post-conception and postnatal days after birth; striped bars) (similar in mice). Different brain regions have asynchronous development; therefore, the general stages of brain development are presented in this image. Discordant schedules of neurodevelopment are evident between the two species. In particular, processes that occur during late gestation in humans take place postnatally in rats. Weaning in rodents is triggered naturally by sexual maturity around three weeks of age, marking the beginning of adolescence/adulthood. It is important to note that different rat and mouse species have innately varied timelines, and for some of the animal models discussed in this review weaning occurred at the natural point for that species, which may be a number of days before or after postnatal day 21.