Introduction:

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy in men in the United States (US).1 While the majority of prostate cancers in the US are diagnosed at the localized stage,1 their clinical course varies widely from indolent to fatal. To facilitate prognostication and disease management, localized prostate cancer can be further classified into low, intermediate, and high risk of progression based on Gleason score, stage, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value at diagnosis.

Many men harbor low-risk disease that will remain clinically insignificant throughout their lifetime. Recognizing that over-treatment of these men would expose them to potentially serious morbidity without deriving any benefit from immediate treatment, major guidelines recommend active surveillance for initial management of this group.2,3 However, in contrast to those with low-risk disease, men with high-risk tumors have a significant risk of symptomatic progression and death from prostate cancer.4,5 In this context, definitive therapy has been shown to decrease disease-specific mortality,6 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend radiation therapy with 2–3 years of androgen deprivation therapy, radiation therapy with brachytherapy with or without 2–3 years of androgen deprivation therapy, or radical prostatectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection as initial treatment of all high-risk localized prostate cancer, barring contraindications2. Despite these recommendations, under-treatment of high-risk disease has been noted in specific groups of patients including the otherwise healthy elderly,7 the un- and under-insured,8,9 and non-White minorities.8–10

Latinos comprise the nation’s largest minority group,11 yet there is a paucity of information regarding prostate cancer treatment in this population. Of concern are reports of an emerging treatment disparity in Latinos with high-risk disease.10 California is home to almost 15 million Latinos, representing 39% of the state’s population, and its largest ethnic group.12 We leveraged the large size of the Latino population and the wealth of data in the California Cancer Registry (CCR) to examine “real-world” treatment patterns and factors affecting the receipt of definitive treatment for high-risk prostate cancer among understudied Latino men.

Methods:

Tumor, demographic, and treatment data on all California Latino and non-Latino White men diagnosed with clinically localized (N0 and M0) adenocarcinoma of the prostate from 2010–2014 were obtained through the CCR. The CCR, comprising four registries within the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program, uses an established algorithm based on medical record ethnicity, surname, and birthplace13 to ascertain Latino ethnicity. The year 2010 was the earliest year that information was available to delineate Gleason scores at biopsy versus prostatectomy, allowing for uniform use of pre-treatment data for risk stratification. The year 2014 marked the last year for which complete data was available.

Prostate cancer cases diagnosed on death certificate or autopsy only (n=25), and those with unknown stage, Gleason score, or PSA were excluded (n=7856). The analysis was limited to men with high-risk disease, defined as having at least one of the following characteristics: Gleason score 8–10, clinical stage T3 or higher, or PSA >20 ng/ml.2 Definitive treatment was defined as radical prostatectomy, radiation (with or without androgen deprivation therapy [ADT]), or cryoablation. Non-definitive therapy included other surgical procedures (e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate), ADT alone, and no treatment. Twelve cases with missing surgery or radiation data for whom it was not possible to determine receipt of definitive treatment were additionally excluded from the analysis, resulting in a final cohort of 8,636 non-Latino and 2,421 Latino cases.

A previously described composite measure14 was used to assign all cases to a tertile of neighborhood socioeconomic status (nSES) based on the 2010 Census block group of their geocoded residence at the time of diagnosis.

The association of ethnicity with receipt of definitive therapy was modeled using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. The multivariable model included tumor factors (clinical T stage, biopsy Gleason score, and PSA value) as well as sociodemographic factors (age, insurance status, marital status, nSES, and care at an NCI-designated cancer center).

To test for heterogeneity in associations by ethnicity, first order interaction terms were examined; significant interactions between ethnicity and several covariates were found. Therefore, the association of treatment with tumor and sociodemographic characteristics was also modeled separately for Latinos and non-Latino Whites.

The proportion of unknown PSA, Gleason score, and stage differed by ethnicity. To address potential bias that could have resulted from the exclusion of those with unknown prognostic factors, a propensity score was created for likelihood of having complete data for all three factors. Analyses were then repeated using inverse probability weighting.15

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Tests were two-sided, with p<.05 considered statistically significant.

Results:

The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. A lower proportion of Latinos received definitive treatment for high-risk localized prostate cancer than non-Latino Whites (74.1% vs. 78.3%). While the proportion of men receiving radiation therapy was similar between groups (42.1% Latinos, 41.1% non-Latino Whites), Latinos were less likely than non-Latino Whites to be treated with radical prostatectomy (31.4% vs. 36.2%). Latinos were more likely to receive non-definitive treatment with ADT alone (13.4% vs. 11.4%) or no treatment (10.6% vs. 8.2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics and first course of treatment of Latino and non-Latino White men diagnosed with high-risk localized prostate cancer in California from 2010–2014.

| Non-Latino White N= 8636 |

Latino N= 2421 |

Total N= 11,057 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Column % | N | Column % | N | |

| Treatment | 6764 | 78.3% | 1793 | 74.1% | 8557 |

| Definitive treatment | |||||

| Radical prostatectomy | 3127 | 36.2% | 759 | 31.4% | 3886 |

| Radiation with ADT | 2688 | 31.1% | 752 | 31.1% | 3440 |

| Radiation without ADT | 865 | 10.0% | 266 | 11.0% | 1131 |

| Cryoablation | 84 | 1.0% | 16 | 0.7% | 100 |

| Non-Definitive Treatment | 1166 | 13.5% | 372 | 15.4% | 1538 |

| ADT monotherapy | 982 | 11.4% | 324 | 13.4% | 1306 |

| Other surgery | 184 | 2.1% | 48 | 2.0% | 232 |

| No treatment documented | 706 | 8.2% | 256 | 10.6% | 962 |

| Clinical T stage | 4325 | 50.1% | 1312 | 54.2% | 5637 |

| T1 | |||||

| T2 | 3209 | 37.2% | 835 | 34.5% | 4044 |

| T3 | 1016 | 11.8% | 249 | 10.3% | 1265 |

| T4 | 86 | 1.0% | 25 | 1.0% | 111 |

| Biopsy Gleason score | 604 | 7.0% | 240 | 9.9% | 844 |

| ≤6 | |||||

| 7 | 1457 | 16.9% | 492 | 20.3% | 1949 |

| 8–10 | 6575 | 76.1% | 1689 | 69.8% | 8264 |

| PSA value | 4069 | 47.1% | 903 | 37.3% | 4972 |

| <10 | |||||

| 10–20 | 1688 | 19.5% | 444 | 18.3% | 2132 |

| >20 | 2879 | 33.3% | 1074 | 44.4% | 3953 |

| Number of unfavorable prognostic factors | |||||

| 1 | 6931 | 80.3% | 1873 | 77.4% | 8804 |

| 2 | 1490 | 17.3% | 480 | 19.8% | 1970 |

| 3 | 215 | 2.5% | 68 | 2.8% | 283 |

| Age | 69 395 |

13 4.6% |

68 180 |

13 7.4% |

69 575 |

| Median (interquartile range) | |||||

| <55 | |||||

| 55–64 | 2125 | 24.6% | 645 | 26.6% | 2770 |

| 65–74 | 3584 | 41.5% | 989 | 40.9% | 4573 |

| 75+ | 2532 | 29.3% | 607 | 25.1% | 3139 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married or domestic partners | 5729 | 66.3% | 1531 | 63.2% | 7260 |

| Never married, divorced, widowed, separated | 2135 | 24.7% | 598 | 24.7% | 1556 |

| unknown | 772 | 8.9% | 292 | 12.1% | 1064 |

| Primary payer | 304 | 3.5% | 143 | 5.9% | 447 |

| No known insurance | |||||

| Not insured/self-pay | 84 | 1.0% | 54 | 2.2% | 138 |

| Unknown | 220 | 2.5% | 89 | 3.7% | 309 |

| Insured | 8332 | 96.5% | 2278 | 94.1% | 10610 |

| Private | 3750 | 43.4% | 993 | 41.0% | 4743 |

| Public/Medicaid | 358 | 4.1% | 452 | 18.7% | 810 |

| Medicare | 3770 | 43.7% | 745 | 30.8% | 4515 |

| Veterans Affairs/ Military | 454 | 5.3% | 88 | 3.6% | 542 |

| Neighborhood SES tertile | 1471 | 17.0% | 1091 | 45.1% | 2562 |

| Lowest | |||||

| Middle | 2914 | 33.7% | 843 | 34.8% | 3757 |

| Highest | 4251 | 49.2% | 487 | 20.1% | 4738 |

| Seen at NCI designated Cancer center | 6810 | 78.9% | 2085 | 86.1% | 8895 |

| No | |||||

| Yes | 1826 | 21.1% | 336 | 13.9% | 2162 |

In comparison to non-Latino Whites, Latinos had a slightly lower proportion of cT3–4 tumors (11.3% vs. 12.8%), lower proportion of high grade tumors (69.8% vs. 76.1%), and higher proportion of PSA values >20 ng/ml (44.4% vs. 33.3%). A higher proportion of Latinos presented with more than one unfavorable disease characteristic (22.6% vs. 19.3%). Latinos tended to be younger than non-Latino Whites at diagnosis, with a higher proportion of cases <65 years old (34.0% vs. 29.2%). The proportion of insured men was similar between groups (94.1% Latinos, 96.5% non-Latino Whites), but the type of insurance coverage differed; compared to non-Latino Whites, a higher proportion of Latinos were covered by Medicaid or public insurance (18.7% vs. 4.1%), and a lower proportion had Medicare coverage (30.8% vs. 43.7%). A lower proportion of Latinos (13.9%) received care at NCI-designated cancer centers compared to non-Latino Whites (21.1%). The distribution of nSES was strikingly different between ethnicities; almost half (45.1%) of Latinos resided in low SES neighborhoods, whereas a similarly high proportion (49.2%) of non-Latino Whites lived in high SES neighborhoods.

In the unadjusted model, Latinos were 21% less likely to receive definitive treatment (odds ratio [OR] 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71–0.88) than non-Latino Whites (Table 2). This association persisted after adjusting for relevant patient and tumor characteristics (age, clinical stage, Gleason score, and PSA; OR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.75–0.95). After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics in addition to age and tumor characteristics, there was no longer a significant difference in the odds of receiving definitive treatment between Latinos and non-Latino Whites (OR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.08).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of receiving definitive treatment for Latino vs. non-Latino White men with high-risk localized prostate cancer

| OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Model A: unadjusted | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) |

| Model B: adjusted for age | 0.72 (0.64–0.80) |

| Model C: adjusted for age and tumor factors (clinical stage, Gleason score, PSA) | 0.84 (0.75–0.95) |

| Model D: adjusted for age, tumor factors (clinical stage, Gleason score, PSA), and sociodemographic factors (marital status, neighborhood socioeconomic status, insurance status, and care at NCI-designated cancer center) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) |

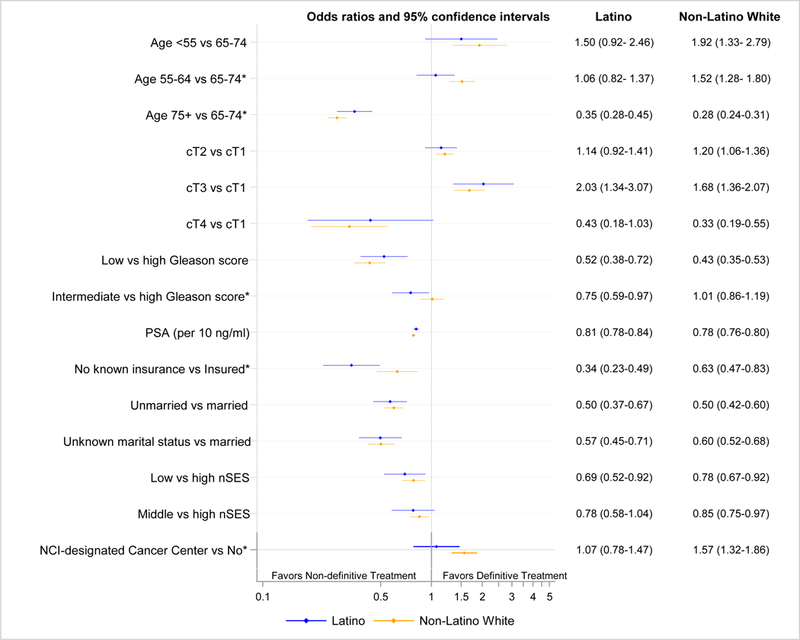

Significant heterogeneity in effects was found with ethnicity and age (Pinteraction=0.005), insurance status (Pinteraction=0.008), and cancer center status (Pinteraction=0.039), prompting us to model the receipt of treatment separately for each ethnic group (Figure 1). The association of age with receipt of treatment was greater for non-Latino Whites than for Latinos; younger age had more than a 1.5-fold greater odds of treatment in non-Latinos (age <55 vs. 65–74: OR=1.92; 95% CI, 1.33–2.79 and age <55 vs. 65–74: OR=1.52; 95% CI, 1.28–1.80), but no significant association in Latinos (age <55 vs. 65–74: OR=1.50; 95% CI, 0.92–2.46; age 55–64 vs. 65–74: OR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.82–1.37).

Figure 1. Association of clinical and non-clinical factors with the receipt of definitive treatment in Latino and non-Latino White men diagnosed with high-risk localized prostate cancer in California from 2010–2014.

*p < 0.05 for Wald test comparing the odds ratios for Latino and non-Latino White men.

Low (≤6) vs. high (8–10) Gleason score had an inverse association with definitive treatment for both non-Latino Whites and Latinos, but the association of Gleason score 7 (GS7) with treatment differed between ethnicities. Non-Latino Whites with GS7 disease were just as likely to receive definitive treatment compared to their counterparts with high grade disease (OR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.86–1.19), whereas Latinos with GS7 disease were less likely to be treated definitively than Latinos with high grade disease (OR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.59–0.97).

While lack of insurance was associated with under-treatment for both ethnicities, the association between being uninsured and lack of definitive treatment was considerably more pronounced for Latinos (OR=0.34; 95% CI, 0.23–0.49) than for non-Latino Whites (OR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47–0.83). Uninsured Latinos were only one third as likely to receive definitive treatment for high-risk disease as those with insurance. Care at NCI-designated cancer centers was associated with a 57% greater odds of definitive treatment in non-Latino men (OR=1.57; 95% CI, 1.32–1.86), but no association was observed for Latinos (OR=1.07; 95% CI, 0.78–1.47).

The associations of stage, PSA, marital status, and nSES with definitive treatment were similar for Latinos and non-Latino Whites.

Discussion:

Men with high-risk localized prostate cancer have significant risk of disease progression and disease-specific mortality, and major guidelines2,3 recommend definitive therapy for all those without contraindications. We found that California Latino men with high-risk localized disease were less likely to receive guideline-concordant care than their non-Latino White counterparts, and this treatment disparity was largely accounted for by sociodemographic factors. However the influence of these factors differed by ethnicity, suggesting that Latino men may interact with healthcare systems differently or face different barriers to care. While extent of disease (as represented by clinical stage and PSA value), marital status, and nSES were similarly associated with definitive treatment for both Latinos and non-Latino Whites, we found that Latinos who were younger, uninsured, or had intermediate grade disease were under-treated relative to non-Latino Whites.

Treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer require a complex risk-benefit analysis which entails an assessment of the risk of symptomatic disease progression and death in light of the patient’s current life expectancy, functional status, and quality of life. Any gains in future life expectancy resulting from treatment must be balanced against potential losses in quality of life. Based on this decision-making framework, younger patients and patients with more aggressive tumors would be most likely to benefit from, and presumably receive, definitive treatment. While this expected association with age held for non-Latino Whites in our study, it was much less pronounced in Latinos. Young Latinos were no more likely to be treated definitively than their 65–74 year old counterparts. Similarly, the effect of disease aggressiveness on receipt of treatment differed between ethnicities. While intermediate grade disease was managed as aggressively as high grade disease in non-Latino Whites, Latinos with intermediate grade disease were less likely to receive definitive treatment than those with high grade disease.

There are many ways in which patient, provider, and system level factors can interact to affect the receipt of appropriate treatment, and obstacles may arise at several points along the treatment continuum. Physician recommendations have been identified as one of the most important factors influencing treatment decisions both among Latinos16,17 and men with prostate cancer.18,19 Yet effective patient-provider communication may be hampered by language barriers and low health literacy in the Latino population.20,21 Ineffective communication of, or differences in perception of, risk of disease progression may play a role in the relative under-treatment of younger Latino men and those with intermediate grade disease. Physician treatment recommendations for Latino patients may also be influenced by implicit bias, which operates unconsciously and is frequently contrary to an individual’s explicit beliefs and values. Implicit bias has been correlated with treatment decisions in several healthcare settings,22 and may inadvertently influence the way information is conveyed and the options that are offered to Latino patients.

Ethnic differences may also exist in patient preference. Patient-reported sexual23 and bowel24 bother following prostate cancer treatment may be worse for Latinos compared to non-Latino Whites, and avoidance of side effects could be driving patient choices. Cultural factors may also play a role. Familism (placing the needs of the family over individual needs), fatalism (sense of lack of control over health and illness), and machismo (male dominant gender roles)25 could result in reluctance to undergo definitive treatment for Latino men.

Social and financial barriers can affect both the decision to get treated and access to treatment. For Latinos, lack of insurance was the socioeconomic factor most strongly associated with under-treatment. This association was much stronger for Latinos than non-Latinos, and suggests that uninsured Latinos face greater obstacles to obtaining safety net care. In California, the responsibility for providing care to the medically indigent rests with individual counties, which vary widely in services provided and eligibility criteria (e.g. income and immigration status).26 The geographic distribution of the Latino population may coincide with availability of more limited safety net services. It is also possible that Latinos may not be as well-informed about the availability of special programs and safety net services and may have difficulties obtaining this information due to language barriers.

We found that lack of insurance and low nSES were independently associated with under-treatment of high-risk localized prostate cancer. The Latino population in California generally has lower income and educational attainment than the non-Latino White population, and Latinos are more likely to work in non-professional occupations such as construction and agriculture.12 The nature of this work may make it difficult to take sufficient time off for treatment, and treatment-related side effects may make continued employment in these industries difficult.21 Even with insurance to cover medical expenses, some Latinos, especially younger men, who are more likely to be primary wage earners, may be less able to withstand the income disruption that accompanies treatment, leading them to forego definitive management of their disease.

Latinos may also be disproportionately affected by healthcare system-level barriers. Availability and quality of care has been shown to differ for Medicaid-insured patients,9,27–29 and a greater proportion of Latinos in our study had Medicaid insurance. Further, receipt of care is often fragmented, requiring visits to several different facilities and providers. For Latinos, language and cultural barriers may compound difficulties navigating such a healthcare system. Despite greater availability of enhanced services such as translators and patient navigators, care at NCI-designated cancer centers was not associated with definitive management for Latinos in our study, suggesting that individual-level factors may exert a stronger influence on receipt of treatment than facility-level factors.

While our study highlights some important differences in receipt of care between Latino and non-Latino White men in California, it has several limitations. First, we excluded patients based on unknown stage, grade, and PSA, and the proportions of patients with unknown values differed by ethnicity. To control for this selection bias, we repeated our analyses, using inverse probability weighting and found that the results of the weighted and unweighted analyses were essentially unchanged (data not shown).

Secondly, the CCR does not record comorbidity and we were unable to determine whether definitive management was contraindicated and appropriately not received. However, it is unlikely that differences in comorbidity burden would explain the observed disparity. While Latinos have a higher prevalence of diabetes and obesity, their prevalence of cardiovascular disease and stroke is lower.30 Moreover, in the US, Latinos have a higher life expectancy than non-Latino Whites,30 suggesting the overall comorbidity burden in the Latino population is not greater than that of the non-Latino White population. Furthermore, the five-year overall survival for a similar cohort of high-risk patients in the CCR diagnosed between 2004–2009 was 78.1% in Latinos and 77.1% in non-Latino Whites, suggesting that regardless of comorbidity status these men would benefit from treatment.

Thirdly, it is possible that some men may have been misclassified with respect to receipt of treatment, especially if they were treated outside of California. While the CCR has data sharing agreements with other states, treatment administered in another country, such as Mexico, would not be captured by the registry. In the 2001 California Health Interview Survey, 1.4% of Latino men reported receiving medical care in another country.31 However, it would have required misclassification of treatment for at least 7.5% of Latino men in our study to eliminate the disparity we observed. Additionally, because others have reported similar treatment disparities in nationwide populations,8,10 it is unlikely that treatment misclassification could completely explain the observed disparity.

Finally, we acknowledge that Latinos are a diverse population; unfortunately, our data do not allow disaggregation by Latino origin. In California, over 80% of Latinos are of Mexican origin,12 and our findings may not generalize to other Latino populations.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to address treatment patterns for high-risk prostate cancer specifically in Latinos. It provides important insights by highlighting ethnic differences in the association of clinical and sociodemographic factors with treatment, thus identifying potential targets for intervention. As a first step, clinicians should be aware that non-clinical factors may be affecting treatment decisions, and should do their utmost to ensure that all men are equally informed of and understand their prognosis and treatment choices. This may be facilitated through the use of interpreters and the availability of culturally-sensitive and language-appropriate informational materials and decision making tools. Increased awareness of potential subconscious biases could also help ensure that treatment options are presented equally to Latino and non-Latino patients. Latino men who are younger, uninsured, or have intermediate grade disease are at higher risk of under-treatment and providers may want to target these groups. The use of resources such as social workers and patient navigators may help to overcome system-level barriers to obtaining appropriate treatment and facilitate community outreach specific to Latino enclaves and low SES neighborhoods

Our study underscores the importance of health insurance for receipt of appropriate treatment, especially for the Latino community. The data from this study preceded the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which increased the availability of health insurance through the expansion California’s Medicaid program and opening of the health insurance marketplace. Yet it is likely that the treatment disparity we observed persists; two years after the implementation of the ACA over half of Californians who lacked health insurance were Latino.32 At a policy level, continued efforts should be made to target uninsured men, either through the implementation of new programs or the expansion of existing programs, such as the IMPACT program, which provides free prostate cancer treatment to un- and underinsured men in California.

Conclusion:

In California, Latinos are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care for localized high-risk prostate cancer than non-Latinos Whites. This treatment disparity may largely be accounted for by sociodemographic factors, suggesting it may be ameliorated through targeted interventions. To be effective, however, such interventions need to address the unique barriers to care in the Latino population.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (D.L.) and by the Stanford Cancer Institute (I.C., S.G). The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement U58DP003862–01 awarded to the California Department of Public Health. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Prostate Cancer. Version 3.2018; 2018.

- 3.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Briers E, et al. EAU- ESTRO - SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Lin Y, DiPaola RS, Yao SL. Fifteen-year Outcomes Following Conservative Management Among Men Aged 65 Years or Older with Localized Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daskivich TJ, Fan KH, Koyama T, et al. Effect of age, tumor risk, and comorbidity on competing risks for survival in a U.S. population-based cohort of men with prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(10):709–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastian PJ, Boorjian SA, Bossi A, et al. High-risk prostate cancer: from definition to contemporary management. Eur Urol. 2012;61(6):1096–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen RC, Carpenter WR, Hendrix LH, et al. Receipt of guideline-concordant treatment in elderly prostate cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(2):332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahal BA, Chen YW, Muralidhar V, et al. National sociodemographic disparities in the treatment of high-risk prostate cancer: Do academic cancer centers perform better than community cancer centers? Cancer. 2016;122(21):3371–3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerhard RS, Patil D, Liu Y, et al. Treatment of men with high-risk prostate cancer based on race, insurance coverage, and access to advanced technology. Urol Oncol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moses KA, Orom H, Brasel A, Gaddy J, Underwood W, 3rd. Racial/Ethnic Disparity in Treatment for Prostate Cancer: Does Cancer Severity Matter? Urology. 2017;99:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Unites States. Vol. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pew Research Center. Characteristics of the Population in California, by Race, Ethnicity and Nativity: 2014. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NAACCR Race and Ethnicity Work Group. NAACCR Guideline for Enhancing Hispanic/Latino Identification: Revised NAACCR Hispanic/Latino Identification Algorithm [NHIA v2.2.1]. Springfield (IL): North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Schupp C, Harrati A, Clarke C, Keegan T, Gomez S. Developing an area-based socioeconomic measure from American Community Survey data. Fremont, CA: Cancer Prevention Institute of California; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(3):278–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrion IV, Nedjat-Haiem FR, Marquez DX. Examining cultural factors that influence treatment decisions: a pilot study of Latino men with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(4):729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo T, Spolverato G, Johnston F, Haider AH, Pawlik TM. Factors that determine cancer treatment choice among minority groups. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeliadt SB, Ramsey SD, Penson DF, et al. Why do men choose one treatment over another?: a review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;106(9):1865–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox J, Amling CL. Current decision-making in prostate cancer therapy. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18(3):275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sentell T, Braun KL. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J Health Commun. 2012;17 Suppl 3:82–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oduro C, Connor SE, Litwin MS, Maliski SL. Barriers to prostate cancer care: affordable care is not enough. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(3):375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson TK, Gilliland FD, Hoffman RM, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in functional outcomes in the 5 years after diagnosis of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4193–4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krupski TL, Sonn G, Kwan L, Maliski S, Fink A, Litwin MS. Ethnic variation in health-related quality of life among low-income men with prostate cancer. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(3):461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanez B, McGinty HL, Buitrago D, Ramirez AG, Penedo FJ. Cancer Outcomes in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: An Integrative Review and Conceptual Model of Determinants of Health. J Lat Psychol. 2016;4(2):114–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latthivongskorn JH-S, Sawait; Wright, Anthony. California’s Uneven Safety Net: A Survey of County Health Care: Health Access Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons JK, Kwan L, Connor SE, Miller DC, Litwin MS. Prostate cancer treatment for economically disadvantaged men: a comparison of county hospitals and private providers. Cancer. 2010;116(5):1378–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SP, Boorjian SA, Shah ND, et al. Disparities in access to hospitals with robotic surgery for patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2013;189(2):514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fossati N, Nguyen DP, Trinh QD, et al. The Impact of Insurance Status on Tumor Characteristics and Treatment Selection in Contemporary Patients With Prostate Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(11):1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD; 2016. [PubMed]

- 31.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. AskCHIS 2001. Went to other country for medical/dental care compared by Race - OMB/Department of Finance. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fronstin P California’s Uninsured: As Coverage Grows, Millions Go Without. California Health Care Almanac; Oakland, CA; 2017. [Google Scholar]