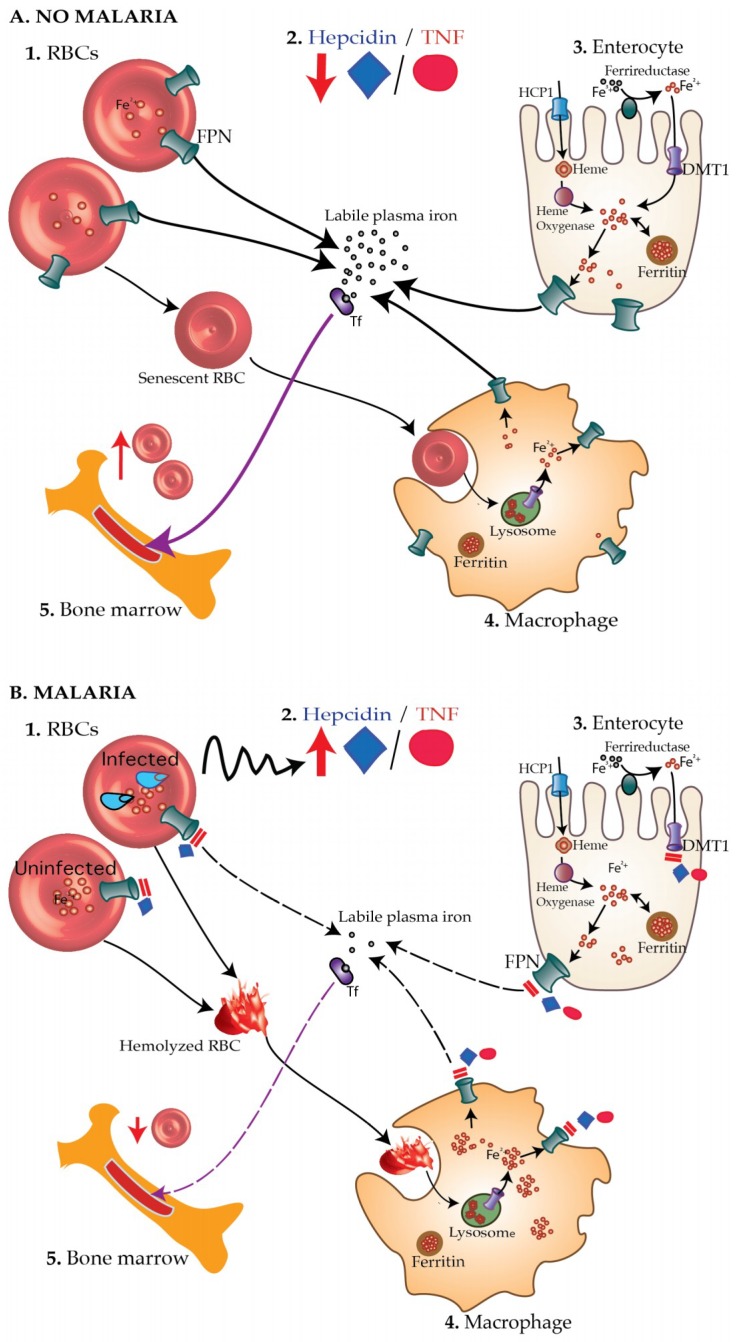

Figure 1.

The malaria—iron deficiency hypothesis. (A) In healthy children without malaria (A1), concentrations of hepcidin and TNF-α are low (A2) leading to increased absorption of iron through enterocytes (A3), reduced hemolysis of RBCs and increased recycling of iron recovered from senescent RBCs by macrophages (A4). More iron is thus available for the production of new RBCs (A5). (B) On the other hand, during malaria infection, blood-stage malaria parasites (B1) elicit increased production of hepcidin and TNF-α (B2), which, in turn, block absorption of iron through DMT1 and ferroportin (FPN) on enterocytes (B3). Hepcidin also degrades ferroportin on both infected and uninfected RBCs leading to accumulation of intracellular iron, oxidative stress, and consequently hemolysis. Hemolyzed RBCs are taken up by the macrophage (B4). Hepcidin and TNF-α inhibit recycling of iron recovered from hemolyzed RBCs back into the circulation leading to deficiency of the amount of biologically available iron. Consequently, little iron is available to produce new RBCs by the bone marrow leading to iron deficiency anemia (B5). Tf, transferrin.