Accurate capture of the symptom experience is essential to gauging efficacy, safety, and tolerability of cancer treatments.1 The Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE™)2 was developed by the National Cancer Institute to allow direct patient self-reporting of symptomatic adverse events in cancer clinical trials.3–5 Its content validity has been established in accordance with recommended practices for novel patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments.6,7

Although we previously reported that the PROCTCAE response options were acceptable to respondents,5 this analysis extends those findings by focusing on comprehension of the response options. For example, can patients delineate between PROCTCAE response options for a given attribute? Does “never/none/not at all” indicate the absence of a symptom, or is it interpreted as the patient is not experiencing a noticeable attribute of that symptom (i.e., a symptom is not severe)? Our aims were to determine if PRO-CTCAE response options are 1) accurately comprehended, including that “never/none/not at all” is selected when the respondent is not experiencing a given symptom and 2) nonoverlapping, that is, able to distinguish respondents with different symptom experiences.

Data were drawn from two studies (NCT01031641 and NCT02158637). For the qualitative phase (NCT01031641), we analyzed data from one-on-one cognitive interviews conducted with 127 patients (59% female, 72% white/non-Hispanic, 35% high-school education or less) receiving treatment for cancer.5 For any symptomatic adverse events (AEs) where a PRO-CTCAE attribute was reported as >0, interviewers asked (for a minimum of two symptoms and their respective attributes per interview): “For this item you chose x, what makes that a better choice than (x + 1)? What makes that a better choice than (x − 1)?” The purpose of this probing was to establish that the patient was considering the difference between proximal responses along the continuum of options.

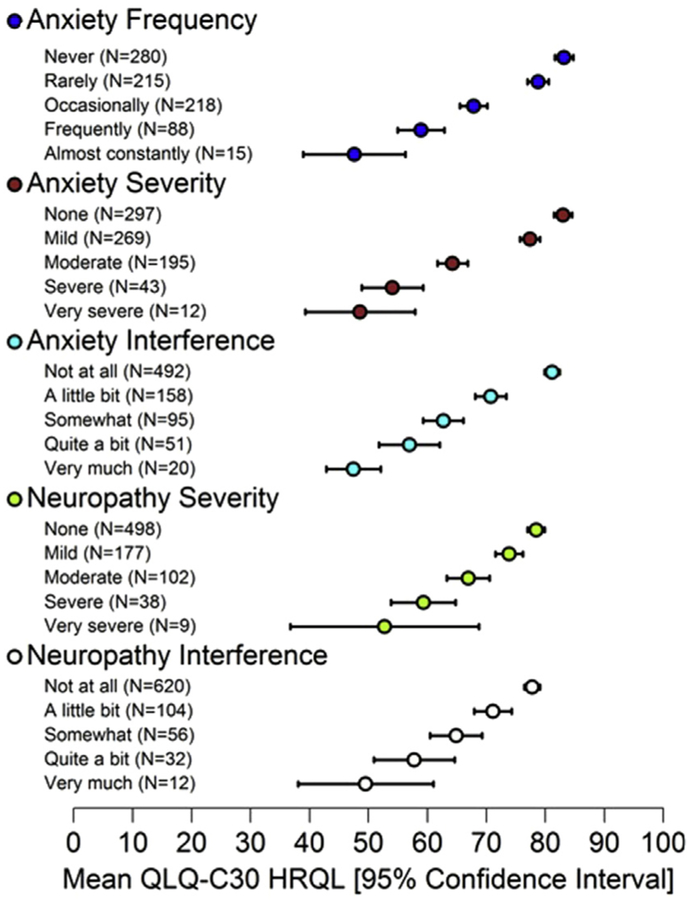

To confirm the monotonicity of PRO-CTCAE response choices, we analyzed data from a psychometric study (NCT02158637) of 940 patients currently undergoing treatment for cancer (57% female, 63% white/non-Hispanic, 32% high-school education or less).4 Patients completed PRO-CTCAE and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30).8 We compared mean EORTC QLQ-C30 Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) summary scores9 across subgroups with worsening PRO-CTCAE item scores using Jonckheere-Terpstra tests.10

Seventy-two of 78 PRO-CTCAE symptom terms (92%) were probed. All respondents with a PROCTCAE item response >0 (99/127) were able to differentiate between adjacent response choices. In the subsample of respondents who selected “never/none/not at all” (35/127) for one or more PROCTCAE items, all participants correctly explained to the interviewer that this response choice meant that they were not experiencing a symptom. For example, a patient was asked about how much dizziness interfered with their usual activities. They selected “somewhat,” defined as “something that might interfere with plans—you wouldn’t take the chance of going somewhere alone.” To this patient, “quite a bit” meant “you wouldn’t be able to go anywhere, even if you had someone with you and needed to get something done.” Another patient was asked why they selected “none” in response to pain severity, to which they responded “I do not experience pain at all.” Additional examples are displayed in Table 1. In the psychometric study, significant (all P < 0.05) monotonically decreasing mean HRQL scores were observed across worsening PROCTCAE score groups for the majority (108/124 [87%]) of PRO-CTCAE items (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Example Patient Explanations of Response Options by Attribute and Adverse Event (N = 127)

| Patient Definition of Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute | Symptomatic Adverse Event | (X − 1) | (X) | (X + 1) |

| Severity | Pain | Moderate—“when you are in pain and it hurts ‘bad, bad’” | Severe—“when you are in pain and it’s getting worse” | Very severe—“when you are in pain and it doesn’t stop and it hurts a lot” |

| Severity | Problems with concentration | Mild—“able to get the task done but may take more time to focus” | Moderate—“takes even more time to get a task done” | Severe—“unable to accomplish a task” |

| Severity | Shortness of breath | Mild—“breathe through the nose only, at a faster pace” | Moderate—“need to breathe through the nose and mouth” | Severe—“fainting or passing out due to the inability to catch a breath” |

| Severity | Felt like nothing could cheer you up | None—“not there” | Mild—“does not feel if it is a reaction” | Moderate—“can recognize it and realize it is a problem” |

| Frequency | Nausea | Occasionally—“every other day or so” | Frequently—“every day I felt some sort of nausea” | Almost constantly—“constantly experiencing nausea” |

| Frequency | Headache | Never—“never happens” | Rarely—“some time during the day” | Occasionally—“three or four times a week” |

| Frequency | Hot flashes | Never—“not once in the last week” | Rarely—“one or two times” | Occasionally—“every other day or so” |

| Interference | Arm or leg swelling | Somewhat—“interfering with 25%–50% of activities in a day” | Quite a bit—“interfering with 50%–75% of activities in a day” | Very much—“interfering with 75%–100% of activities in a day” |

| Interference | Fatigue | A little bit—“doesn’t interfere with daily activities much—wouldn’t put off gardening” | Somewhat—“would put off gardening but be able to do something less strenuous” | Quite a bit—“wouldn’t be able to do another activity that was more strenuous than gardening” |

| Interference | Frequent urination | A little bit—“I’m aware of it and may have to compensate for it” | Somewhat—“you have to make more compensation but not interfering too much (don’t have to call in sick to work)” | Quite a bit—“having to miss work or social events” |

| Amount | Hair loss | Not at all—“none, not noticeable” | A little bit—“hair falling out naturally” | Somewhat—“noticing more than usual on the brush” |

X refers to the patient response, with X − 1 representing the proximal lower response choice and X + 1 representing the proximal higher response choice on the response scale for a specific attribute.

Fig. 1.

Mean European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) summary scores (higher scores represent better HRQL) show statistically significant declines across worsening Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Item Response.

In response to probing, all study participants provided accurate and meaningful explanations for selection of a given PRO-CTCAE response over its proximal alternatives. Moreover, all participants indicated that choosing “never/none/not at all” meant the symptom was absent. Statistically significant, conceptually relevant associations between PRO-CTCAE response choices and HRQL were seen across a substantial majority of the PRO-CTCAE items.

Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that PRO-CTCAE response options are well comprehended and that each of the ordinal response choices is nonoverlapping, serving to distinguish respondents with meaningfully different symptom experiences.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute contracts HHSN261200800043C and HHSN261200800001E, as well as a National Institutes of Health support grant (P30 CA08748-50), which provides partial support for the Patient-Reported Outcomes, Community-Engagement, and Language Core Facility. The sponsors had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or decision to submit the report for publication.

Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02158637 and NCT01031641.

Contributor Information

Thomas M. Atkinson, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Jennifer L. Hay, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Amylou C. Dueck, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA.

Sandra A. Mitchell, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Tito R. Mendoza, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA.

Lauren J. Rogak, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Lori M. Minasian, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Ethan Basch, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

References

- 1.Kluetz PG, Chingos DT, Basch EM, Mitchell SA. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: measuring symptomatic adverse events with the National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2016;35:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). National Cancer Institute - Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences. Available from https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 3.Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106: dju244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay JL, Atkinson TM, Reeve BB, et al. Cognitive interviewing of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual Life Res 2014;23:257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 1-eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011;14: 967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 2-assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011;14: 978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85:365e376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonckheere AR. A distribution-free k-sample test against ordered alternatives. Biometrika 1954;41:133. [Google Scholar]