Abstract

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal-dominant inherited genetic disease. High-throughput sequencing quickly and comprehensively detects causative variants of FH-related genes (LDLR, PCSK9, APOB and LDLRAP1). Although the presence of causative variants in FH-related genes correlates with future cardiovascular events, it remains unclear whether detection of causative gene mutation and disclosure of its associated cardiovascular risk affects outcomes in patients with FH. Therefore, this study intends to evaluate the efficacy of counselling future cardiovascular risk based on genetic testing in addition to standard patients’ education programme in patients with FH.

Methods and analysis

A randomised, waiting-list controlled, open-label, single-centre trial will be conducted. We will recruit patients with clinically diagnosed FH without previous history of coronary heart disease from March 2018 to December 2019, and we plan to follow up participants until March 2021. For the intervention group, we will perform genetic counselling and will inform an estimated future cardiovascular risk based on individuals’ genetic testing results. The primary endpoint of this study is the plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level at 24 weeks after randomisation. The secondary endpoints assessed at 24 and 48 weeks are as follows: blood test results; smoking status; changes of lipid-lowering agents’ regimen and Patients Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form scores among the four groups divided by the presence of genetic counselling and genetic status of FH.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects and all other applicable laws and guidelines in Japan. This study protocol was approved by the IRB at Kanazawa University. We will disseminate the final results at international conferences and in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

UMIN000029375.

Keywords: familial hypercholesterolemia, genetic testing, genetic counseling, cardiovascular risk

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This would be the first randomised, waiting-list controlled study to assess whether disclosing the risk for future cardiovascular diseases based on genetic testing results correlates with reduced low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) over standard FH education.

This study design is pragmatic; thus, the study results could be applied for daily clinical practice of primary prevention in patients with FH.

For patients without causal variants in FH-related genes, disclosure of relatively low-risk for future cardiovascular risk may inversely increase plasma LDL cholesterol levels compared with high-risk individuals with causal variants in FH-related genes. This may attenuate the intervention effect on the primary endpoint.

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder and the prevalence of patients with heterozygous FH in the general population is approximately 0.5%–0.2% (1 in 200–500 individuals).1–5 The major causative genes of FH are low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (LDLR), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), apolipoprotein B (APOB) and LDLR adaptor protein 1 (LDLRAP1). As FH is characterised by hyper LDL-cholesterolemia and systemic xanthomas from infancy, it is one of the leading causes of premature coronary artery disease.6 Typically, patients with FH are prescribed lipid-lowering agents at an early stage to reduce plasma LDL cholesterol levels, which could prevent future occurrence of systemic arteriosclerosis including coronary artery disease. Hence, it is imperative to give a precise diagnosis of FH as early as possible.7

According to the Japanese Atherosclerosis Society guideline, the clinical diagnosis of FH in patients aged >15 years are made if the two of the following three criteria are met: (1) hyper LDL-cholesterolemia; (2) presence of tendon xanthomas and (3) family history of FH or premature coronary artery disease.1 Although genetic testing by the Sanger sequencing method is crucial for the definitive diagnosis of FH, it is performed only in some limited institutions because of its cost, large effort and complexity. In addition, it remains unclear whether genetic testing offers some advantages on the diagnosis or outcomes in patients where FH has already been diagnosed clinically.

In recent years, advancements in comprehensive genetic analysis technology using a high-throughput sequencer have facilitated checking variants in candidate genes cost-effectively and promptly. Previously, we conducted comprehensive genetic testing for patients clinically diagnosed with FH and suggested that the carriers of causative variants in FH-related genes (LDLR, PCSK9, APOB or LDLRAP1) could be associated with future cardiovascular events.8 In addition, the presence of causative variants in FH-related genes has been reported to be associated with cardiovascular events, irrespective of LDL cholesterol levels.9 Based on these results, genetic testing could be useful from the perspective of cardiovascular risk estimates and stratification of patients with FH. However, it remains unclear whether genetic testing with informing future cardiovascular risk based on the results affects the prognosis in patients with FH.

Thus, this study aims to evaluate whether informing genetically estimated future cardiovascular risk based on genetic testing besides usual patient education correlates with reduced LDL cholesterol levels in patients with FH.

Methods and analysis

Overall study design

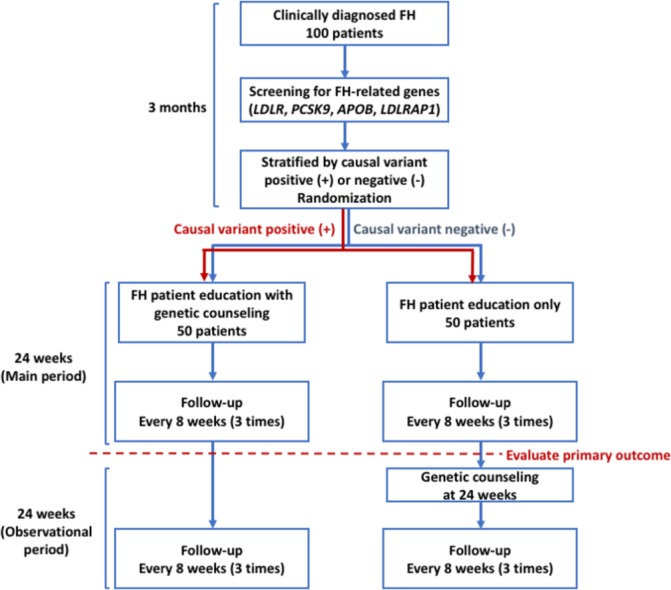

This study is a randomised, waiting list controlled, open-label, single-centre trial. For the intervention group, we will perform genetic counselling as well as informing individual genetically estimated future cardiovascular risk based on patients’ genetic testing results. Figure 1 shows the scheme of this study, and table 1 outlines the overall follow-up schedule. The primary outcome of this study is the plasma LDL cholesterol level at 24 weeks after randomisation. In addition, we hypothesise that the intervention group would have lower LDL cholesterol levels compared with the control group at 24 weeks.

Figure 1.

Scheme of this study protocol. FH, familial hypercholesterolemia.

Table 1.

Assessment and evaluation schedule of this study

| 12 Weeks before randomisation | Day 0 (Week 0) | Week 8 Week 16 |

Week 24 | Week 32 Week 40 |

Week 48 | |

| Diagnosed with clinical FH (pre-registration) | Randomisation (registration) |

Main period | Primary endpoint | Observational period | Trial end | |

| Informed consent | X | |||||

| Patient background | X | |||||

| Check adverse events |

|

|||||

| Height | X | |||||

| Body weight | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| BP/HR | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Symptoms | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Physical examination | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Blood tests | ||||||

| Lipid profile | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| FPG/HbA1c | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| CBC | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Chemistry | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Genetic testing | X | |||||

| Lipid-lowering therapy regimen | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| PSQ-18 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Smoking status | X | X | X | X | X | X |

BP, blood pressure; CBC, complete blood counts; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HR, heart rate; PSQ-18, the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form.

This study will be conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects and all other applicable laws and guidelines in Japan. In addition, this study protocol was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN ID: UMIN000029375).

Study participants

We will recruit patients with clinically diagnosed FH from March 2018 to December 2019, and we plan to follow up participants until March 2021. Of note, only participants fulfilling all inclusion criteria will be enrolled in this study (box 1) and those with either of the exclusion criteria were excluded from this trial (box 2). In addition, we will obtain written informed consent from all trial participants and these forms were approved by the IRB at the Kanazawa University Hospital (online supplementary data 1). It will be mandatory for trial participants to understand the contents of the consent form before giving their acceptance; moreover, it will have to be dated and signed by both trial participants and investigators. On obtaining consent, the first copy of the consent form will be kept in the hospital and the other part was kept by the patient and will not be collected after the completion of the trial. Furthermore, all participants will be informed that their medical care will not be affected if they refused to enrol in the trial and that they will be free to withdraw their consent at any time of the study period, at their discretion.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria.

We include the patients with all the following criteria:

Age ≥15 years.

Diagnosed with familial hypercholesterolemia per the criteria of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society.

Patients who have never got genetic tests or have not yet returned genetic results regarding familial hypercholesterolemia.

Patients who can provide written informed consent.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

We exclude patients with either of the following criteria:

Liver dysfunction (AST or ALT>3 times the UNL).

Renal dysfunction (Cr, ≥2.0 mg/dL).

Immunosuppression.

Active cancer.

-

Previous history of coronary heart disease:

Myocardial infarction.

History of percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft.

Coronary stenosis (≥75%) previously detected by coronary angiography.

Female with pregnancy or expected.

Patients whose doctors in charge consider him/her inappropriate to participate.

bmjopen-2018-023636supp001.pdf (365.1KB, pdf)

Screening FH causal variant

We will sequence exons of four FH-related genes (LDLR, PCSK9, APOB and LDLRAP1) using the Illumina MiSeq system. The variant is defined as FH causal when it fulfils either of the following criteria: (1) registered as pathogenic/likely pathogenic in the ClinVar database; (2) minor allele frequency <1% in the East Asian population with (i) protein-truncating variants (nonsense, canonical splice sites or frameshift) and (ii) missense variants that five in silico damaging scores (SIFT, PolyPhen-2 HDIV, PolyPhen-2 HVAR, MutationTaster2, LRT), all predicted as pathogenic;9 (3) missense variants reported as pathogenic in the Japanese population: PCSK9 p.Val4Ile and p.Glu32Lys10 11 and (4) eXome-Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) software predicted as copy number variations (large duplication/large deletion).12

Intervention and control

Regarding the intervention group, we will perform genetic counselling besides standard FH patient education. In addition, a single qualified doctor will inform genetically estimated future cardiovascular risk based on the result of genetic testing. Genetic counselling will comprise the following: (1) genetic diagnosis; (2) outline of what FH is; (3) checking family history of hyperlipidaemia/cardiovascular diseases; (4) informing that the results of genetic testing could facilitate the research in this field and (5) explaining the physical/mental support system in our hospital. Of note, this counselling will be provided by a qualified physician of clinical genetics. In addition, we will inform ORs of future cardiovascular risk, based on the presence or absence of (1) a causal genetic variant and (2) a clinical sign (xanthomas and/or family history of FH) by using the original Japanese documents (online supplementary data 2).8 9 After counselling, we will set time to answer the queries of patients adequately, confirming their level of understanding.

bmjopen-2018-023636supp002.pdf (108.1KB, pdf)

Regarding the control group, we will only disseminate standard FH patient education using the Japanese booklet for FH patient education according to the FH management guideline;1 this education will be provided by a clinical cardiology physician specialist. After the education, we will set time to answer the queries of patients adequately. After evaluating primary endpoint (24th week from randomisation), the control group will receive their genetic testing results and future cardiovascular risks via counselling as the intervention group receives.

Both groups will be followed-up until 48th weeks from randomisation. Furthermore, it will be possible to receive additional counselling and/or outpatient visit when patients want or are afraid of genetic testing regardless of the intervention or control groups during and after the trial.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of this study is the plasma LDL cholesterol levels at 24 weeks. In addition, secondary endpoints assessed at 24 and 48 weeks are as follows: blood test results; smoking status; changes of lipid-lowering agents’ regimen and Patients Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) scores between the intervention and control groups or among the four groups taking genetic testing results (positive/negative) into consideration ((1) intervention+positive; (2) intervention+negative; (3) control+positive and (4) control+negative).

Follow-up schedule

Table 1 lists the overall follow-up schedule for this study. Follow-up visits will be conducted in an outpatient clinic at the Kanazawa University Hospital. We will check patients’ background profiles, height, body weight, blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), subjective/objective symptoms, complete blood counts, chemistry, lipid profile, Lp(a), fasting glucose, haemoglobin A1C, lipid-lowering agents’ regimen, PSQ-18, smoking status and genetic testing. In addition, data regarding patients’ background profiles, including age, sex and medical history, will be obtained. We expect to arrange regular follow-up visits at 8 weeks (±14 days), 16 weeks (±14 days), 24 weeks (±14 days), 32 weeks (±14 days), 40 weeks (±14 days) and 48 weeks (±14 days) to evaluate patients’ body weight, BP/HR, symptoms, blood test results, prescription, adherence to prescribed medication by self-report, PSQ-18 and smoking status. Furthermore, we will evaluate the primary outcome at 24 weeks and recorded adverse events and concomitant medication throughout the trial.

Data monitoring will be conducted by an independent monitoring staff. The trial institution will be monitored after the first randomisation and every 6 months until the case report form of the last participant is obtained. Trial database will also be monitored and reviewed by the staff and data queries will be raised if necessary.

Sample size and power

The plasma LDL cholesterol levels at 24 weeks are the primary endpoint of this study. Of note, the estimated difference in the LDL cholesterol level between the intervention and control groups was 15 mg/dL with a SD of 25. In the sample size calculation, we determined that the required patients per group were 44 with 95% CI and power of 80%. Moreover, we set the drop rate as 10% and approximately 100 patients with FH were required for this trial.

Randomisation

We will randomise patients with FH using an independent web-based randomisation system that included a minimisation algorithm balanced for age (≥50 years and <50 years), gender (male and female) and causative variant, positive or negative. This system automatically allocates patients’ to either the intervention or control groups. Only principal investigator, trial physicians and the clinical trial research coordinators have access to the clinical, laboratory and allocation data. Of note, researchers performing statistical analyses will be blinded to the allocation.

Statistical analysis

We will compare the outcomes between intervention and control groups. The baseline profiles are described by the mean and SD or median and quantiles (continuous variables) or proportion (categorical variables). In addition, we will assess the primary endpoint based on the intention-to-treat fashion, which was compared between the groups using the t-test. Moreover, we will compare secondary endpoints between the groups at each defined period using the t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test, Fisher’s exact test or linear or logistic regression adjusted by appropriate covariates. Finally, p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant for the primary endpoint. Statistical analysis will be performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) or R software V.3.4.1 or above (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public will not be involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures; the design of this study; the assessment of the intervention in this study; or the recruitment to and conduct of the study. We will disseminate the final results to the study participants after the results are published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Discussion

For this study to demonstrate the clinical efficacy of informing cardiovascular risk based on genetic testing results, it is imperative to confirm the FH diagnosis by genetic testing and to provide thoughtful evidence that genetic testing-based cardiovascular risk disclosure could enhance the prognosis of patients with FH. Furthermore, it might be possible to further advance precision medicine based on causal gene variants currently proposed mainly in the USA.13

This study will enrol patients with FH without a history of coronary heart diseases (CHD). Reportedly, patients with FH are at high risk of CHD compared with those without FH.1 14 In addition, patients with FH with causal variant positive in FH-related genes are more likely to be diagnosed with CHD than those without a causal variant in FH-related genes.8 9 Thus, the target plasma LDL cholesterol level is <100 mg/dL for primary prevention in patients with FH.1 However, the achievement rate of target LDL cholesterol levels remains around 20%, despite appropriate lipid-lowering drug prescription.15 Beyond lipid-lowering agents, encouraging behavioural changes by the disclosure of genetic testing results is the focus of attention. In a recent randomised trial, Kullo et al reported that the disclosure of future CHD risk by evaluating the genetic risk score correlated with the declining LDL cholesterol level at 6 months in patients with general hypercholesterolemia.16 The results of our study could prove that the risk stratification by genetic testing result and the disclosure of future cardiovascular risk can promote patients’ behavioural changes and can elucidate the benefit of attaining the target of LDL cholesterol and thus might further reduce plasma LDL cholesterol levels.

In this study, the primary endpoint is the changes in the plasma LDL cholesterol levels following the disclosure of future CHD risk based on a genetic testing result. Reportedly, LDL cholesterol is a primary risk factor for CHD and lipid-lowering therapy and a healthy lifestyle play a crucial role in reducing LDL cholesterol level.1 6 17 We have already standardised assays previously to assess the lipid profile and we evaluated the LDL cholesterol level directly or by the Friedewald formula.18 In addition, we will assess whether changes in LDL cholesterol are because of changes in the lipid-lowering therapy regimen, behaviour change, lifestyle modification or a combination of them. Furthermore, we assessed patients’ mental status such as satisfaction or anxiety to genetic testing, genetic counselling, disclosure of future CHD risk, a change in the treatment regimen and doctor-patient relationship at outpatient clinic visits.

The strength of genetic testing is that we will be able to precisely inform the personalised genetic information and future CHD risk and also be able to ameliorate participants’ inner bad emotions for their diseases and decision makings over treatment. Thus we will check the PSQ-18 as one of the secondary endpoints to objectively assess patients’ understanding and satisfaction for the daily medical practice, disclosure of genetic risk, treatment decisions and medical costs. Lewis et al reported that genetic counselling after standard education might improve the satisfaction of individuals who have received their carrier results.19 Our study might provide interesting perspectives of returning genetic results with the disclosure of future CHD risk for patients with FH, who have reliable and evidence-based treatment options to prevent the risk.

In conclusion, we aimed to demonstrate the study design and protocol of the Impact of genetic testing on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with FH (GenTLe-FH) study. This study would be the first randomised controlled trial investigating the clinical efficacy of the disclosure of future CHD risk based on genetic testing results in patients with FH. We hypothesise that the intervention group has a lower plasma LDL cholesterol level than the control group at 6 months after randomisation. Finally, this study will provide insights into the importance of genetic testing and its disclosure of cardiovascular risk in patients with FH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all the participants and staff in this study. We also thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: AN, HT, HO, AN and M-aK designed and conducted the study. KY and HI gave us critical comments on statistical methods. All authors performed a critical review and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by the Innovative Clinical Research Center Kanazawa University (iCREK) Clinical Research Seed Grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study protocol (V.2.0, dated 27 August 2018) was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kanazawa University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Oikawa S, et al. . Guidelines for the management of familial hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb 2012;19:1043–60. 10.5551/jat.14621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gidding SS, Champagne MA, de Ferranti SD, et al. . The Agenda for Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;132:2167–92. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watts GF, Gidding S, Wierzbicki AS, et al. . Integrated guidance on the care of familial hypercholesterolaemia from the International FH Foundation. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:309–25. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al. . Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3478–90. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mabuchi H, Nohara A, Noguchi T, et al. . Molecular genetic epidemiology of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in the Hokuriku district of Japan. Atherosclerosis 2011;214:404–7. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Versmissen J, Oosterveer DM, Yazdanpanah M, et al. . Efficacy of statins in familial hypercholesterolaemia: a long term cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a2423 10.1136/bmj.a2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teramoto T, Kobayashi M, Tasaki H, et al. . Efficacy and Safety of Alirocumab in Japanese Patients With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia or at High Cardiovascular Risk With Hypercholesterolemia Not Adequately Controlled With Statins- ODYSSEY JAPAN Randomized Controlled Trial. Circ J 2016;80:1980–7. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Nohara A, et al. . Impact of clinical signs and genetic diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia on the prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with severe hypercholesterolaemia. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1573–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khera AV, Won HH, Peloso GM, et al. . Diagnostic Yield and Clinical Utility of Sequencing Familial Hypercholesterolemia Genes in Patients With Severe Hypercholesterolemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2578–89. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mabuchi H, Nohara A, Noguchi T, et al. . Genotypic and phenotypic features in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia caused by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gain-of-function mutation. Atherosclerosis 2014;236:54–61. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohta N, Hori M, Takahashi A, et al. . Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 V4I variant with LDLR mutations modifies the phenotype of familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2016;10:547–55. 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K, et al. . Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:597–607. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jameson JL, Longo DL, medicine-personalized P. problematic, and promising. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, et al. . Familial hypercholesterolemia: screening, diagnosis and management of pediatric and adult patients: clinical guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2011;5:133–40. 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galema-Boers AM, Lenzen MJ, Engelkes SR, et al. . Cardiovascular risk in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia using optimal lipid-lowering therapy. J Clin Lipidol 2018;12:409–16. 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kullo IJ, Jouni H, Austin EE, et al. . Incorporating a Genetic Risk Score Into Coronary Heart Disease Risk Estimates: Effect on Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels (the MI-GENES Clinical Trial). Circulation 2016;133:1181–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. . 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 20142014;63:2889–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis KL, Umstead KL, Johnston JJ, et al. . Outcomes of Counseling after Education about Carrier Results: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hum Genet 2018;102:540–6. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023636supp001.pdf (365.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023636supp002.pdf (108.1KB, pdf)