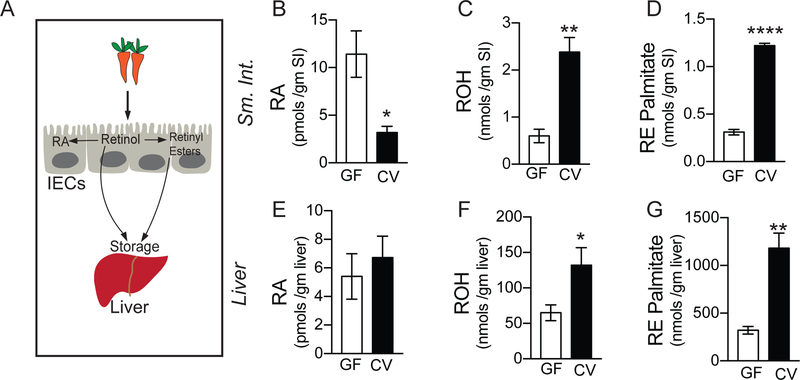

Figure 1. Gut commensals modulate intestinal and extra-intestinal vitamin A metabolism.

(A) Diagram representing vitamin A absorption by the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) and storage in the liver. Once taken up by IECs, Vitamin A (retinol) can be directly or after being processed into retinyl esters stored in the liver. Retinol can be also be metabolized into its active form, retinoic acid (RA) by IECs.

(B) Quantification of retinoic acid (RA) in the small intestine (SI) of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS.

(C) Quantification of retinol (ROH) in the small intestine (SI) of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS.

(D) Quantification of retinyl ester palmitate (RE) in the small intestine (SI) of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS.

(E) Quantification of retinoic acid (RA) in the liver of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS.

(F) Quantification of retinol (ROH) in the liver of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS.

(G) Quantification of retinyl ester palmitate (RE) in the liver of germ-free (GF) and conventional mice (CV) performed using LC-MS, (N=4 per group). Student’s t-test. Error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

Also see Supplemental Table 1