Abstract

Background:

Altered joint laxity may contribute to joint dysfunction. Knee joint laxity has been shown to increase during pregnancy, but its long-term persistence is unknown.

Objective:

To determine whether pregnancy leads to lasting increases in knee joint compliance and laxity that persist greater than 4 months postpartum.

Design:

Prospective cohort study

Setting:

A motion analysis laboratory at an academic medical center.

Participants:

Fifty healthy women in their first trimester of pregnancy with mean±SD age of 29.2±4.3 years and baseline BMI of 26.0±5.4 kg/m2 were recruited.

Methods:

End-range knee laxity and mid-range joint compliance were measured during first trimester and 19±4 weeks postpartum. Anterior-posterior and varus-valgus laxity were measured using 3D motion tracking while applying forces/moments in each respective plane using the Vermont Knee Laxity Device. Non-linear models were constructed to assess relationships between applied forces and joint translation, comparing early pregnancy with postpartum.

Main Outcome Measurements:

Multiplanar knee laxity and compliance.

Results:

Peak varus-valgus (20–22%; p=.001) and posterior translation (51%; p<.001) of the tibia relative to the femur decreased from baseline, with a concomitant reduction in laxity (p<.001) and compliance (p=.039) in the coronal plane and in the posterior direction in both primiparous (p=.009) and multiparous (p=.014) women. For primiparous women, laxity (p<.001) and compliance (p=.009) increased in the anterior direction.

Conclusions:

Pregnancy resulted in lasting decrease in multiplanar knee laxity and compliance in the varus and posterior directions with increase in anterior compliance. The effects of these changes in laxity and compliance of the passive stabilizers on knee loading patterns, articular contact stresses and risk for OA and other musculoskeletal disorders will require additional research.

Introduction

Women are at elevated risk for knee osteoarthritis (OA), although the mechanism for this elevated risk in comparison with men is unclear.[1] One exposure that differs between women and men is pregnancy. Pregnancy results in numerous changes in women’s bodies in preparation for delivery. Some of these changes may be indelible and predispose women to increased risk for lower limb musculoskeletal disorders later in life, considering that parous women are more likely than nulliparous women to suffer from musculoskeletal disorders.[2,3,4,5]

Elevated levels of estrogen and relaxin during pregnancy increase flexibility and remodeling of collagen in the knees and other joints.[6] Altered joint biomechanics due to a lasting change in joint laxity may cause supraphysiological stress on musculoskeletal tissues. Additionally, increased joint laxity could lead to cartilage stresses of greater magnitude or in a different distribution. Exposure to abnormal contact stresses can be detrimental to the joint.[7,8] It has been suggested that increased joint laxity during pregnancy is responsible for knee problems, such as chondromalacia patella.[9] Additionally, investigators have reported that altered gait mechanics may lead to elevated focal joint loading.[10] As excessive tibiofemoral contact stresses are known to increase risk for cartilage loss,[10] alterations in loading due to changes in knee joint laxity could be relevant to understanding the mechanism for OA development.

Joint laxity in the knees increases during pregnancy and is sustained into the immediate postpartum period.[11] However, since prior studies have not assessed laxity at greater than six weeks postpartum, it is unknown if knee joint laxity returns to pre-pregnancy levels. Some researchers have suggested that joints with increased laxity may not fully return to pre-pregnancy values after the first pregnancy and that laxity develops more rapidly during subsequent pregnancies in comparison with the first.[12]

The knees are the weight-bearing joints most commonly affected by OA[13] and women are at higher risk than men for developing knee OA; therefore, there is a need to determine whether pregnancy results in alterations in knee joint laxity that persist long-term. The knee transmits large intersegmental loads due to body weight and muscle forces. Altered laxity and surface shape, from remodeling of the cartilage matrix components within the knee, increase articular contact stress.[14] This stress may lead to injury of joint structures. Determining the extent to which increased knee joint laxity and compliance— the ease with which an object can be deformed— persist following pregnancy could provide insight into a potentially modifiable risk factor for the higher prevalence of knee OA in women. Thus, the purpose of this study was to assess if knee joint laxity and compliance differ between the first trimester of pregnancy and 4–5 months postpartum. We also sought to assess if there is a difference between primiparous and multiparous women regarding change in knee joint laxity and compliance during this period. We hypothesized that pregnancy leads to a lasting increase in compliance and knee joint laxity.

Methods

Participants

Healthy women (n=50) between the ages of 18 to 40 years and in their first trimester of pregnancy volunteered for the study (Table 1). Volunteers were identified through advertisements at women’s clinics, family medicine clinics, student health services, primary care providers’ offices, daycare facilities, elementary schools, first-trimester pregnancy classes, mass e-mails, newspaper and web-based press releases and a medical center cafeteria news bulletin. Participants were categorized by parity level as primiparous or multiparous, as previous data has suggested a threshold exists for changes in foot structure and joint laxity that occurs in conjunction with a second pregnancy.[15] Exclusion criteria included: participation in in-vitro fertilization, prior lower limb joint surgery or spinal surgery, chronic diseases known to affect collagen metabolism, and immobility or history of surgery that restricted walking for more than 2 days.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Characteristics (Mean (SD))

| Parity Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primiparous (N=27) | Multiparous (N=21) | |

| Baseline Age (years) | 27.4 (3.8) | 31.8 (4.4) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 (5.7) | 27.1 (5.6) |

| Follow-up BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 (3.9) | 27.3 (5.3) |

| Body mass change between baseline and follow-up (kg) | 3.0 (2.8) | 0.2 (3.6) |

| Valgus Knee Displacement (degrees) | −1.5 (1.0) | −1.5 (0.9) |

| Varus Knee Displacement (degrees) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.9) |

| Anterior Knee Displacement (mm) | 7.7 (2.6) | 7.6 (2.7) |

| Posterior Knee Laxity (mm) | −3.7 (2.0) | −3.2 (2.0) |

| Valgus Knee | −0.21 (0.01) | −0.25 (0.01) |

| Compliance (degrees/Nm) | ||

| Varus Knee Compliance (degrees/Nm) | −0.22 (0.01) | −0.26 (0.02) |

| Anterior Knee Compliance (mm/N) | −0.06 (0.00) | −0.05 (0.00) |

| Posterior Knee Compliance (mm/N) | −0.07 (0.00) | −0.06 (0.00) |

Measurements were completed during first trimester (10±1 weeks gestation) and at 19±4 weeks postpartum. If participants lost their pregnancy or delivered prior to 36 weeks, they were not contacted for follow-up and no change data were available for analyses. The first trimester was chosen, as knee joint laxity at that time has been reported to be within 10% of pre-pregnancy values.[11] During the first visit, all participants completed an institutional research board-approved informed consent process. At the postpartum follow-up visit, all measurements and tests were repeated.

Measures

Pregnancy Information and Health Questionnaire

Each participant’s medical record was reviewed for body mass (kg), height (cm), BMI (kg/m2), and pregnancy information, including delivery date and body mass at delivery. Participants also completed a medical history questionnaire at baseline and follow-up visits. This questionnaire included information regarding the number of previous pregnancies, as well as history of ankle, knee, or foot surgeries or injuries prior to the baseline visit and during the current pregnancy up to the point of follow-up.

Multiplanar Knee Laxity and Compliance

Laxity was defined as the displacement of the tibia relative to the femur under non-weight bearing conditions with peri-articular muscles relaxed and was determined by the amount of translation that occurred with application of a fixed force or moment. Compliance, which is the inverse of stiffness, was defined as the resistance to displacement of the tibia relative to the femur when a force was applied and was determined by analyzing the midrange slope of the force-translation and moment-angular displacement curves for the sagittal and coronal planes, respectively.

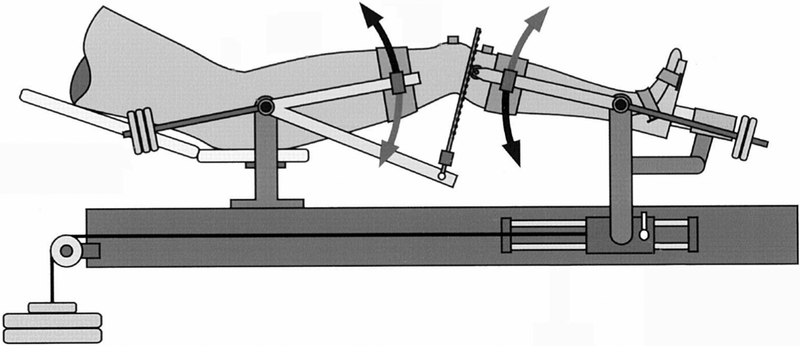

Shank length (the distance between maximal lateral protuberance of the lateral femoral condyle and the lateral malleolus) was measured to determine the applied force needed to achieve 10 Nm varus/valgus moment (VR/VL) about the tibiofemoral joint. A laced ankle brace was then applied to each participant’s right foot and the researcher tightened the lacings. This minimized motion at the ankle when the force was applied at the medial malleolus. Participants lay supine on the Vermont Knee Laxity Device (VKLD, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT), which firmly secured the lower limb and allowed each anatomic plane to be measured in isolation and the validity and reliability has been demonstrated in women in this age group.[16,17,18] A researcher securely strapped the participant’s right foot into the foot cradle, aligned the rotational axis of the shank support with the medial-lateral directed axis that passed though the medial and lateral malleoli, and the long axis of the tibia was then rotated to align the second metatarsal with the right anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). The greater trochanter was aligned with the rotational axis of the thigh support. Then, the thigh was secured by placing the thigh pad 3–4 finger-widths superior to the patella and by tightening the medial and lateral pads. The pinion of the shank support, where the rack would insert, was aligned with the tibial plateau. Similarly, the shank pad was placed 3–4 finger-widths distal to the tibial tuberosity, with the shank strap loosened for VR/VL testing and tightened for anterior/posterior (A/P) translation. Counterweights were applied to the thigh and shank to create initial zero shear and axial compressive loads at the tibiofemoral joint (Figure 1). These levels were monitored by an oscilloscope throughout data collection and adjusted to maintain this unweighted condition.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Vermont Knee Laxity Device (VKLD) limb positioning and counterweights

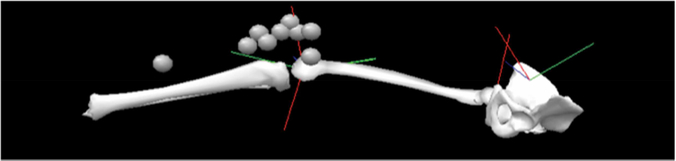

Three-dimensional marker positions (Optotrak, Northern Digital Inc, Waterloo, ON) were collected at 60 Hz. Infrared emitting diode markers were placed on the lower limb, with triads on the patella and tibial tuberosity, a single marker on the distal tibia, and two markers on a post extending from the medial femoral epicondyle (Figure 2). Another post was placed on the lateral femoral epicondyle and the two posts were tightened to the knee with elastic bands. Three markers were attached to the VKLD as the reference markers for the pelvis, which was assumed to be stationary once strapped into the VKLD. Several landmarks (medial and lateral malleoli, tibial tuberosity, medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, right greater trochanter, and ASIS) were digitized manually to create an individualized scaled model in Visual 3D software (C-Motion, Germantown, MD) before the femoral epicondylar markers were applied. A static trial was collected with the knee in 20 degrees of flexion, which was maintained for each trial. The static trial was used to define the coordinate systems of the right foot, shank, thigh and pelvis.

Figure 2.

Schematic of lower limb motion analysis marker placement.

To measure VR/VL laxity and compliance, an alternating external force was applied at the medial malleolus continuously in medial-lateral direction using a handheld load cell (Omega S Beam, LC 105, Stamford, CT) to produce the limits of 10 Nm of VR/VL torques about the knee. For A/P, alternating forces were applied to the tibial tuberosity in a continuous manner from anterior to posterior to reach the target 95 N force using a rack and pinion that connected the swing-arms of the thigh and shank support, while a force sensor (Model 9820, Advanced Force Measurement, Scottsdale, AZ) was connected in series with the rack to monitor the applied force. Participants were familiarized with the laxity protocol by cycling through each set of motions once, and then two acceptable trials were collected at each force threshold, each of which consisted of three cycles of motion. The order of trials was VR/VL, VR/VL, A/P, A/P. All analog data were sampled at 360 Hz. Day-to-day reliability testing has demonstrated that 68% of VR/VL angular displacements are within 1.2° of the measured value, and 95% are within 2.5°.[16] For A/P translation, inter-rater reliability was 2.0±2.4 mm for two raters.[17]

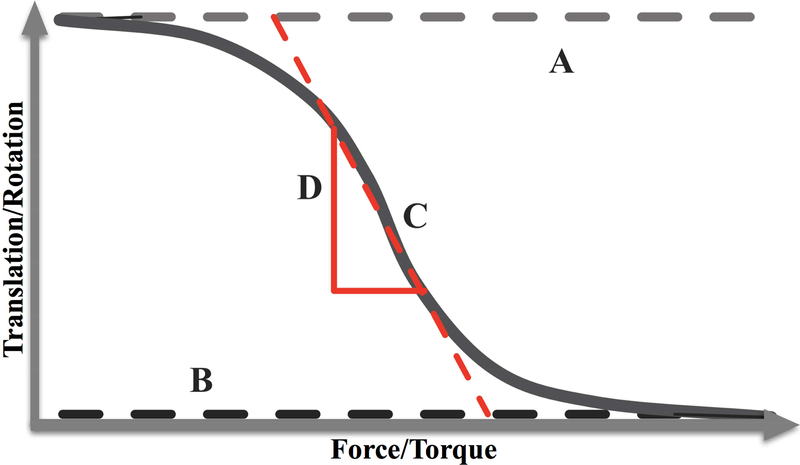

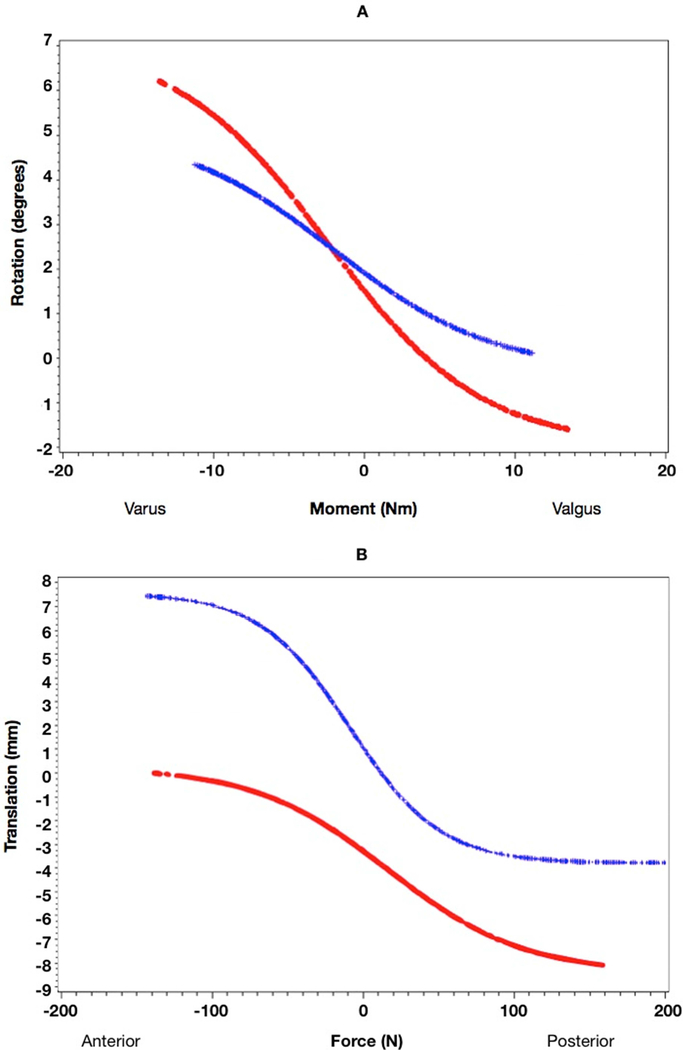

Compliance was measured as the slope (D) of the force (moment) by translation (rotation) plot at the point (C) midway between the limits of the range of motion, A and B (Figure 3 and formula below).[19] A larger absolute value of D indicates that more translation/rotation occurred with a given force/moment (i.e., more compliant) while a smaller absolute value of D indicates that less translation/rotation occurred with a given force/moment (i.e., less compliant). Thus, a decreased D value signifies decreased compliance, and an increased D value signifies increased compliance.

Figure 3.

Graphical display of an idealized knee joint compliance curve. A is the upper limit of translation (rotation), B is the lower limit of translation (rotation), C is the midpoint in the range of motion, and D is the slope (compliance) at point C.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) with significance set at p<.05. Subject characteristics were summarized for continuous measures in each parity group. Two parity groups were formed: primiparous and multiparous. Second and third pregnancies were grouped to form the multiparous group. Non-linear mixed models for repeated measures (2 time points, random intercept) were used to assess significant changes in the end-range knee laxity. For each trial in each participant, displacement vs. applied force or moment was plotted and individually assessed for internal validity and consistency. Nonlinear models were constructed to assess for changes in compliance using PROC NLIN with the equation above. Compliance (D-values) and laxity were compared between baseline and follow-up using mixed models to control for multiple trials per participant and two visits, while weighting for the average root-mean square error to standardize participants’ curves for comparison.

While there were no available data for the expected change in knee laxity with pregnancy, using similar methods to ours, Schmitz et al. reported that varus stiffness (the inverse of compliance) in women was approximately 0.7±1.4 Nm/degree less than in men at an applied torque of 10 Nm.[20] For a two-tailed comparison of matched baseline vs. postpartum paired measurements with this magnitude and variance of change, at an alpha level of 0.05, a sample size of 44 women would provide 90% power. Accounting for up to a 12% drop-out, a sample size of 50 women were recruited.

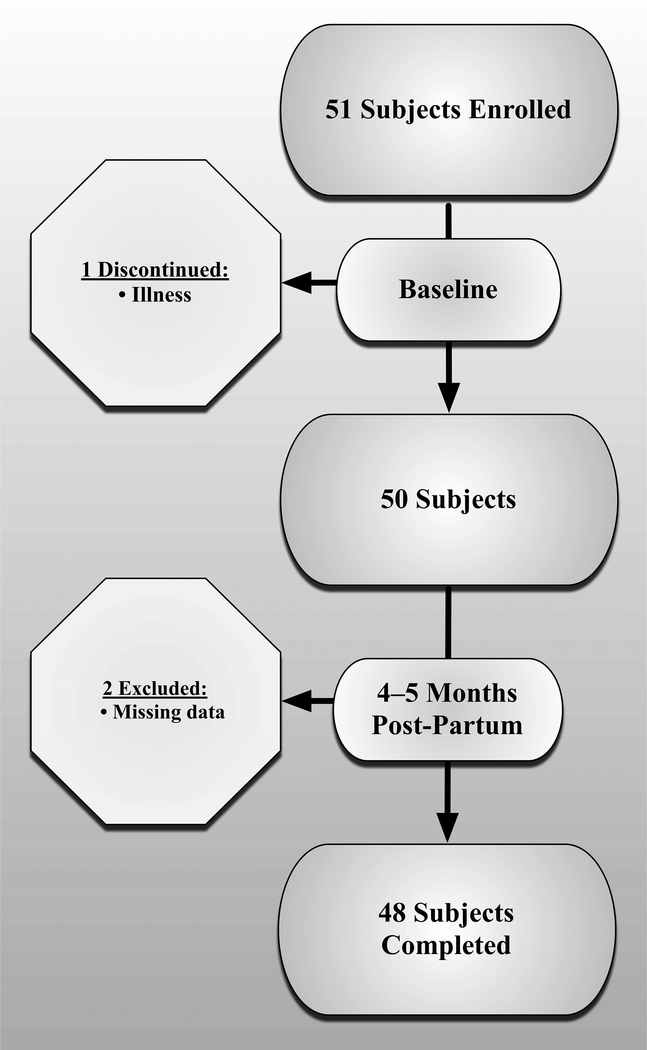

Results

For the 50 women who completed the baseline visit, mean±SD age was 29.2±4.3 years and baseline BMI was 26.0±5.4 kg/m2. Age differed between primiparous and multiparous participants (p<.001). However, baseline BMI and follow-up BMI did not statically differ between parity groups (p>0.5) (Table 1). After the 4–5 months postpartum follow-up visit, two participants were missing marker data for A/P laxity, leaving 48 participants with analyzable datasets (Figure 4). Characteristics for the 48 participants who completed the entire study are summarized in Table 1. Participants were in their first (N=28), second (N=17) and third or greater pregnancy (N=3).

Figure 4.

Enrollment and Participant Flow Diagram

Laxity

There were statistically significant reductions in laxity in the coronal plane (20–22%; p=.001) and in the posterior direction (51%; p<.001) over the study period for both primiparous and multiparous women (Tables 2 and 3). Regarding laxity in the anterior direction, there was a statistically significant increase in primiparous women (p<.001; with a significant interaction between time and parity). Peak values decreased from baseline in the coronal plane as well as in the posterior direction for both primiparous and multiparous groups. Anterior translation increased in primiparous women and tended to decrease in multiparous women (Table 3). Examples of reduction in coronal plane and posterior laxity and increase in anterior laxity are depicted in Figures 5a and 5b.

Table 2.

Mean (SE) change in end-range varus/valgus knee laxity between baseline and follow-up with a 10 Nm applied moment.

| Primiparous | p-value | Multiparous | p-value | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valgus Knee Laxity (degrees) | −0.4 (0.1) | <.001 | −0.4 (0.1) | <.001 | −0.4 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Varus Knee Laxity (degrees) | −0.4 (0.1) | <.001 | −0.3 (0.1) | .005 | −0.3 (0.1) | <.001 |

Table 3.

Mean (SE) changes in end-range anterior/posterior knee laxity between baseline and follow-up with a 95 N applied force.

| Primiparous | p-value | Multiparous | p-value | All | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Knee Laxity (mm) | 0.7 (0.2) | <.001 | −1.2 (0.7) | .09 | 0.0 (0.1) | .99 |

| Posterior Knee Laxity (mm) | −1.7 (0.1) | <.001 | −1.5 (0.1) | <.001 | −1.6 (0.1) | <.001 |

Figure 5.

a) Sample data for reduction in coronal plane laxity measurements; b) Sample data for reduction in posterior and increase in anterior laxity measurements (baseline data plotted in red and follow-up data plotted in blue)

Compliance

Changes in knee compliance over the study period are displayed in Tables 4 and 5. Compliance in the posterior direction decreased for both parity groups and overall, whereas there was greater compliance in the anterior direction for the primiparous group and overall, but not in the multiparous group. In the coronal plane, there were no significant changes in varus knee compliance in primiparous or multiparous women, but there was a decrease overall, and valgus compliance did not change.

Table 4.

Mean (SE) changes in mid-range varus/valgus knee compliance between baseline and follow-up with a 10 Nm applied moment.

| Primiparous | p-value | Multiparous | p-value | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valgus Knee Compliance (degrees/Nm) | −0.01 (0.01) | .364 | −0.02 (0.01) | .174 | −0.01 (0.01) | .115 |

| Varus Knee Compliance (degrees/Nm) | −0.01 (0.01) | .280 | −0.04 (0.02) | .077 | −0.02 (0.01) | .039 |

Table 5.

Mean (SE) changes in mid-range anterior/posterior knee compliance between baseline and follow-up with a 95 N applied force.

| Primiparous | p-value | Multiparous | p-value | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Knee Compliance (mm/N) | 0.01 (0.00) | .051 | 0.01 (0.01) | .073 | 0.01 (0.00) | .007 |

| Posterior Knee Compliance (mm/N) | −0.02 (0.01) | .009 | −0.01 (0.01) | .014 | −0.02 (0.00) | <.001 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether anterior-posterior and varus-valgus knee laxity increased between the first trimester of pregnancy and approximately 5 months postpartum. The knees studied demonstrated lasting changes with pregnancy, though different from the hypothesized direction. Joint laxity and compliance decreased in the coronal plane and in the posterior direction, while compliance increased in the anterior direction. While the cohort as a whole changed for some variables, the magnitude of change was relatively small compared to day-to-day reliability thresholds [16,20]. It is unknown what magnitude of change in joint laxity and compliance constitute clinical relevance, but highlights an area for future research.

The findings may provide insight into parity as a potential risk factor for the higher prevalence of knee OA in women than men. Associations between higher parity and decreased total knee cartilage volume and patellar cartilage defects may provide a direction for investigation to advance understanding regarding this sex difference.[3] The various factors that have been proposed to explain the link between parity and OA, however, require further exploration.

To our knowledge, no prior studies examined whether pregnancy results in persistent changes in ligamentous laxity and compliance at the knee joint or characterized these parameters in a controlled manner. In addition, previous studies evaluated knee laxity with devices that did not account for the shear loads due to the mass of the lower limb, and which may contribute to increased joint laxity.[11] Segment mass may create a large increase in laxity which either increases a minimal increase or masks a decrease resulting from the actual knee structures.

Though we did not measure postural changes in this study, postural changes during pregnancy may have contributed to our findings. As pregnant women experience an anterior shift in center-of-gravity, their knees hyperextend to maintain balanced, upright posture.[21] Knee hyperextension tenses the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) as it impinges against the femoral notch, which may cause the ACL to adapt and lengthen throughout pregnancy.[22,23] Static stress focused on the anterior portion of the knee may also cause a decrease in chondrocyte metabolism,[24] which could contribute to further hyperextension. The resultant tissue remodeling that occurs during pregnancy could cause instability if the knee returns to a non-hyperextended state postpartum as counterbalancing forces are altered in the postpartum knee. The knee is delicately balanced to maintain stability while also allowing for a wide range-of-motion during activities. Perturbations to this balance, such as those caused by the non-uniform changes in joint laxity which persist following pregnancy, could potentially increase the risk of developing OA and other musculoskeletal disorders in women in their post-reproductive years. However, long-term studies would be necessary to clarify such an effect as these potential mechanisms remain hypothetical at this time. Brage et al examined knee laxity in individuals with OA and found that OA knees had less laxity than control knees (57% less AP, 33% less ML) indicating that reduced laxity is associated with knee OA.[25]

Although we hypothesized that knee joint laxity would increase, as has been found during pregnancy, we found a lasting reduction in laxity in the posterior direction and in the coronal plane. Misbalanced forces acting on the knee are known to cause abnormal joint kinetics. For example, increased and anteriorly displaced center of mass in pregnancy causes hyperextension of the knee.[21] It is possible that the non-uniform changes in laxity associated with pregnancy (i.e. decreased laxity in varus/valgus and posterior directions without a decrease in the anterior direction) could cause adverse changes in this manner. Previous studies have revealed a relationship between knee joint laxity and OA progression,[25,26] but risk factors for the development of incident OA differ from those involved in progression of the disease.[27] Other perturbations to homeostasis that may cause imbalanced loading at the knee joint include decreased compliance, as detected in this study in the varus and posterior directions. Prior reports indicating that OA is related to either increased or decreased knee joint laxity may support this bi-directionality.[25,26]

This study was limited by a number of factors. It did not include any direct measurements of the transient stress-strain conditions within the knee joint tissues that may influence cartilage and meniscal health. Restrictions on imaging in the first trimester precluded measures that would provide clear visualization of knee joint structures. Therefore, laxity in various directions could not be attributed to specific structures, but rather was generalized to net translation/rotation. Although our purpose focused on alterations in knee joint laxity and compliance that persist 4–5 months postpartum, it would have been useful to have pre-pregnancy measurements of laxity and compliance to better track changes. Longitudinal studies will be necessary to assess whether the lasting changes in knee joint laxity and compliance may explain a portion of the relationship between parity and elevated risk for knee OA. Determining whether therapies aimed at preventing or ameliorating laxity have an effect on reducing risk for knee joint damage, could be useful in determining whether a causal association exists.

Conclusions

In the women studied, there were changes in joint laxity and compliance that persisted from pregnancy to postpartum and differed based on the direction of motion. Joint laxity and compliance decreased in the coronal plane and in the posterior direction. An increase in compliance was seen in the anterior direction only in primiparous women. Further research is warranted to determine if there is a causal relationship between these findings and the established elevated risk for knee OA in women.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the dedication of the participants who committed their time to making this study possible. This study also benefitted from the recruitment efforts of Ms. Ranae Molkenthin. Funding was provided by an American Geriatrics Society 2006 Dennis W. Jahnigen Career Development Scholars Award and National Institutes of Health Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research (1K23AG030945) and Short-Term Training for Students in Health Professions (5T35HL007485) grants.

No conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article. Funding was provided by an American Geriatrics Society 2006 Dennis W. Jahnigen Career Development Scholars Award and a National Institutes on Aging Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging Research (1K23AG030945). The sponsors for the study were not involved in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or decision to publish this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.D’Ambrosia RD. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Orthopedics 2005; 28(2 Suppl):s201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal NA, Felson DT, Torner JC, et al. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: epidemiology and associated factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88(8):988–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei S, Venn A, Ding C, et al. The associations between parity, other reproductive factors and cartilage in women aged 50–80 years. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19(11):1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise BL, Niu J, Zhang Y, et al. The association of parity with osteoarthritis and knee replacement in the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21(12):1849–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vullo VJ, Richardson JK, Hurvitz EA. Hip, knee, and foot pain during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Fam Pract 1996; 43(1):63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blecher AM, Richmond JC. Transient laxity of an anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knee related to pregnancy. Arthroscopy 1998; 14(1):77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal NA, Anderson DD, Iyer KS, et al. Baseline articular contact stress levels predict incident symptomatic knee osteoarthritis development in the MOST cohort. J Orthop Res 2009; 27(12):1562–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segal NA, Kern AM, Anderson DD, et al. Elevated tibiofemoral articular contact stress predicts risk for bone marrow lesions and cartilage damage at 30 months. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20(10):1120–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artal R, Masaki DI, Khodiguian N, Romem Y, Rutherford SE, Wiswell RA. Exercise prescription in pregnancy: weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing exercise. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161(6 Pt 1):1464–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andriacchi TP, Koo S, Scanlan SF. Gait mechanics influence healthy cartilage morphology and osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 Suppl 1:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schauberger CW, Rooney BL, Goldsmith L, Shenton D, Silva PD, Schaper A. Peripheral joint laxity increases in pregnancy but does not correlate with serum relaxin levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174(2):667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumas GA, Reid JG. Laxity of knee cruciate ligaments during pregnancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1997; 26(1):2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41(8):1343–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heijink A, Gomoll AH, Madry H, et al. Biomechanical considerations in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20(3):423–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calguneri M, Bird HA, Wright V. Changes in joint laxity occurring during pregnancy.Ann Rheum Dis 1982; 41(2):126–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shultz SJ, Shimokochi Y, Nguyen AD, Schmitz RJ, Beynnon BD, Perrin DH. Measurement of varus-valgus and internal-external rotational knee laxities in vivo--Part I: assessment of measurement reliability and bilateral asymmetry. J Orthop Res 2007; 25(8):981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uh BS, Beynnon BD, Churchill DL, Haugh LD, Risberg MA, Fleming BC. A new device to measure knee laxity during weightbearing and non-weightbearing conditions. J Orthop Res 2001; 19(6):1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beynnon BD, Fleming BC, Labovitch R, Parsons B. Chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency is associated with increased anterior translation of the tibia during the transition from non-weightbearing to weightbearing. J Orthop Res 2002; 20(2):332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beardsley CL, Howard AB, Wisotsky SM, Shafritz AB, Beynnon BD. Analyzing glenohumeral torque-rotation response in vivo. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2010; 25(8):759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz RJ, Ficklin TK, Shimokochi Y, et al. Varus/valgus and internal/external torsional knee joint stiffness differs between sexes. Am J Sports Med 2008; 36(7):1380–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo H, Shin D, Song C. Changes in the spinal curvature, degree of pain, balance ability, and gait ability according to pregnancy period in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Journal of physical therapy science 2015; 27(1):279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dehghan F, Haerian BS, Muniandy S, Yusof A, Dragoo JL, Salleh N. The effect of relaxin on the musculoskeletal system. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer EG, Baumer TG, Haut RC. Pure passive hyperextension of the human cadaver knee generates simultaneous bicruciate ligament rupture. Journal of biomechanical engineering 2011; 133(1):011012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sah RL, Kim YJ, Doong JY, Grodzinsky AJ, Plaas AH, Sandy JD. Biosynthetic response of cartilage explants to dynamic compression. J Orthop Res 1989; 7(5):619–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brage ME, Draganich LF, Pottenger LA, Curran JJ. Knee laxity in symptomatic osteoarthritis. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1994; (304):184–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wada M, Imura S, Baba H, Shimada S. Knee laxity in patients with osteoarthritis andrheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1996; 35(6):560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper C, Snow S, McAlindon TE, et al. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(5):995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]