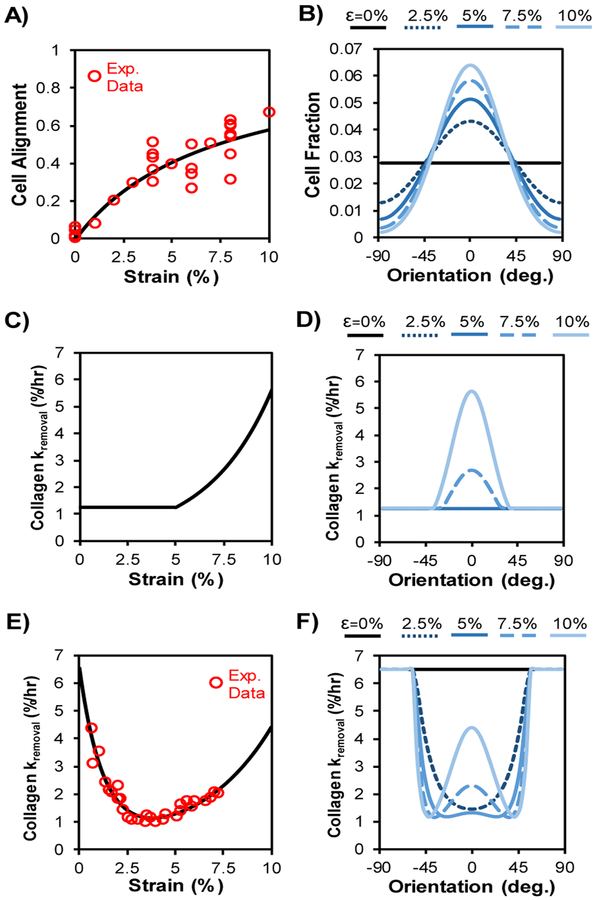

Fig. 2. Cell alignment and collagen removal depend on strain.

(A) Cell alignment increased as a function of maximum principal engineering strain according to Eq. 1, fit to published experimental data (Wang and Grood 2000; Neidlinger-Wilke et al. 2001, 2002; Loesberg et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2008; Houtchens et al. 2008; Ahmed et al. 2010; Prodanov et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2013; Tamiello et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016). (B) Cell orientation probability distribution was set as a wrapped normal distribution according to Eq. 4 and the strength of alignment cues; curves shown here indicate the distributions that would be observed in response to the strain levels indicated, in the absence of any matrix alignment cues. (C) For strain-dependent damage simulations, we assumed collagen damage exponentially increased the rate of removal of fibers experiencing strain above a damage threshold according to Eq. 8. (D) Since fiber strain depended on orientation, collagen damage resulted in preferential removal of fibers oriented near the global tissue strain direction, as indicated by higher values of kremoval for those orientation bins. (E) For strain-dependent enzymatic degradation simulations, we fit previous experimental measurements that demonstrated collagen degradation by proteases depends nonlinearly on strain according to Eq. 9 (Huang and Yannas 1977). (F) Simulated uniaxial stretch led to different fiber strains for fibers with different orientations, which together with the nonlinear curve in (E) yielded varying distributions of kremoval for different applied strains.