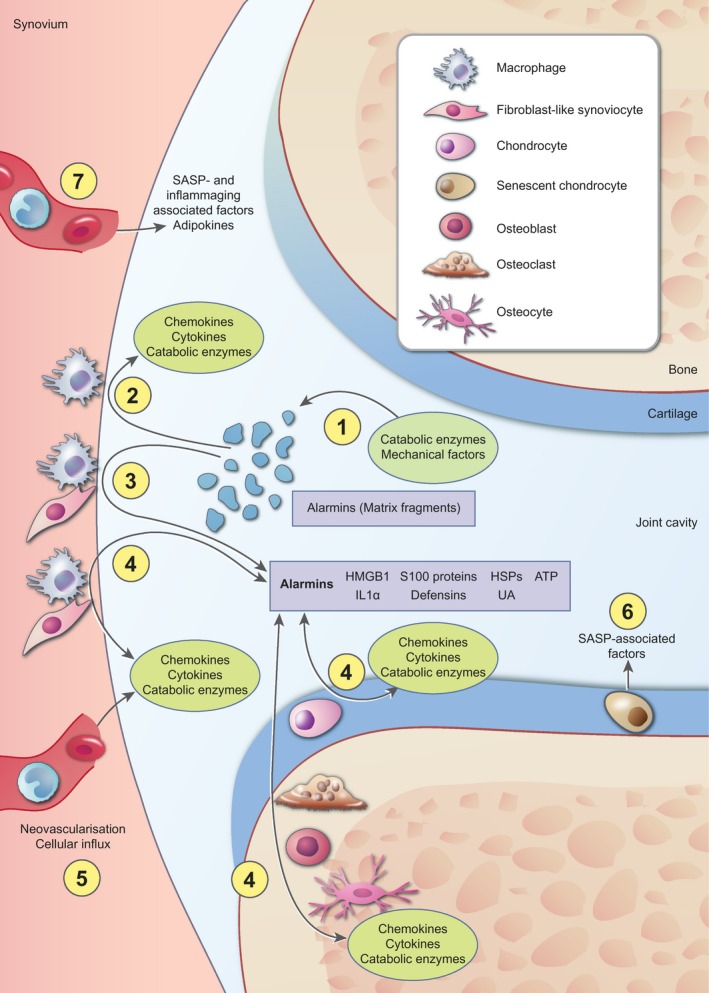

Figure 1.

Overview of the processes that contribute to inflammation in osteoarthritis. Nowadays it is well accepted that inflammation is present and actively involved in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis (OA). The most broadly supported view is that cartilage extracellular matrix fragments, released as the result of an initial trauma or catabolic enzyme activity (a), increase synovial inflammation by stimulation of cells in the synovial lining. Activated synovial cells start to produce proinflammatory factors, such as chemokines, cytokines and catabolic enzymes (b). In addition, these cells secrete high levels of various alarmins, such as high‐mobility group box‐1 (HMGB1) and S100 proteins (c). These alarmins initiate a positive‐feedback loop with reciprocal production of chemokines, cytokines and catabolic enzymes, on one hand, and alarmins on the other hand, not only in synovial cells, but also in cells in the cartilage and periarticular bone (d). Growth factors and chemokines add to the inflammatory process in the joint by stimulating neovascularization and influx of inflammatory cells that also start to produce chemokines, cytokines and catabolic enzymes (e). In addition, cellular senescence is associated with an increased release of factors, such as many cytokines and catabolic enzymes, referred to as senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which further stimulates the inflammatory state of the joint (f). Finally, systemic changes are associated with inflammation during OA. Increased systemic levels of inflammatory mediators as the result of SASP or ageing and adipokines as the result of increased fat mass contribute to the inflammatory milieu in the joint (g). Together, these factors are thought to be involved in the pathological processes that take place during OA, such as hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes and breakdown of the articular cartilage, fibrosis in the synovial tissue, sclerosis of the subchondral bone and ectopic bone formation (these processes are not depicted in this figure).