Abstract

Backgrounds/objectives:

Acne is an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit (PSU). The over-expression of survivin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I in some fibrotic disorders suggests a possible implication in the pathogenesis of acne and or post-acne scar. We aimed to evaluate their potential role in pathogenesis in acne and post-acne scar.

Methods:

Serum survivin and IGF-I levels were estimated in 30 patients with acne and post-acne scar compared to 30 controls.

Results:

There was a statistically significant difference in survivin and IGF-I levels between controls and patients (P < 0.05). However, there was no linear correlation between survivin and IGF-I.

Conclusions:

Survivin and IGF-I could have a possible role in the pathogenesis of active acne and in post-inflammatory acne scar.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, survivin, IGF-I

Lay Summary

We selected 30 patients with acne and post acne scar versus age and sex matched 30 controls to evaluate role of survivin and IGF-1 in reflecting severity of disease and liability for post acne scar, so in those patients early treatment should started.

We found that higher statistical significant levels of survivin and IGF-1 in patients than control and positive correlation between survivin with severity of acne.

We also found that Patients with high BMI have more severe acne and post acne scar, so decreasing BMI is a vital step in ttt of acne

Local use of potential Survivin and IGF1 antagonists in treatment of acne and post acne scar

Introduction

Acne is a recurrent inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units mainly at sites with a high proportion of sebaceous glands (SG) such as the face (99%), back (60%) and chest (15%).1 Microcomedone is the earliest subclinical ‘lesion’ in acne that may change into open and closed comedones and into different inflammatory lesions, such as papules, pustules, nodules and cysts.2 Scarring is the end result of skin damage during the healing process with a significant impact on life quality.3

Human survivin is a 16.5 kDa protein, encoded by the BIR containing 5 (BRIC5) gene and spans 14.7 kb at the telomeric position of chromosome 17(17q25).4 Survivin is a unique member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family expressed in the majority of human tumours, but is barely detected in normal adult tissue, including skin.5 Survivin over-expression in tumours is generally associated with poor prognosis due to its apoptotic inhibitory effect.6

Abnormal apoptosis and enhanced sebocyte survival mediated by survivin might affect infundibular keratinocyte differentiation and altered sebum production, leading to comedo formation and acne.7

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I is encoded by the IGF-I gene with 70 amino acids in a single chain and three disulphide bridges.8

IGF-I stimulates 5α-reductase, adrenal and androgen synthesis, androgen receptor signal transduction, sebocyte proliferation and lipogenesis leading to increase acne lesion and sebum secretion.9

IGF-I is impeded in pathogenesis and progression of many fibrotic disorders including post-acne scars through stimulation of fibroblasts proliferation and increasing messenger RNA levels of procollagen-I.10

Material and methods

The present study was a case-control cross-sectional study that was conducted on 60 individuals during the period from February to May 2017: 15 active acne patients; 15 post-acne scar patients; and 30 apparently healthy controls.

Inclusion criteria

The following individuals were recruited to participate in the study after obtaining informed consent: any patient presenting with acne vulgaris who did not receive any treatment for three months or post-inflammatory acne scars with no history of previous skin resurfacing; no active infection; no use of oral isotretinoin in the previous six months; and aged 13–30 years.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with a history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chronic or acute hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, benign or malignant tumours, and any other kind of cutaneous or fibrotic lesions were excluded from the study.

Informed consent

After approval of the Research Ethical Committee (REC), Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Examination

-

The weight and height for each patient were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated11:

Dermatological examination of the distribution, type of lesions and severity of acne using a simple acne grading system.12 It classifies acne as follows: mild = comedones and papules; moderate = comedones, papules and pustules; and severe = all of the above plus nodules and cysts.

In the case of post-inflammatory acne scar, dermatological examination including the type of lesions and severity of scar: mild = mild atrophy or hypertrophy that may not be apparent at social distances of ⩾ 50 cm and can be masked easily by makeup; moderate = moderate atrophic or hypertrophic scarring that is clear at social distances of ⩾ 50 cm and cannot be masked easily by makeup; and severe = severe atrophic or hypertrophic scarring that is clear at social distances of ⩾ 50 cm and cannot be masked easily by makeup.13

Full physical examination to exclude any systemic illness associated with survivin and IGF-I level.

Specimen collection

A total of 4 mL of blood was collected from each individual in the study from the ante-cubital vein by veni-puncture. Blood samples were collected in plain vacutainer tubes for serum separation. They were incubated at 37 °C for 10–15 min and were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm to separate serum. Serum samples were divided into two aliquots for later measurements of survivin and IGF-I.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 18 in Windows 7. The data obtained in the study were expressed as mean ± SD. Independent Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA test were used to compare quantitative data of independent groups. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative groups. Bivariate Pearson correlation test was used to examine the association between variables. A P value < 0.05 was considered the cut-off value for significance.

Results

The present case-control cross-sectional study included 60 individual in the period from February to May 2017 (30 acne patients: 15 active acne and 15 post-acne scar patients) not suffering from any other skin disorders. Data were compared to 30 healthy controls who were age-, sex- and BMI-matched.

There was no statistically significant difference between acne and post-acne scar patients regarding family history, degree of disease severity and duration.

There was a high statistically significant difference in serum survivin and serum IGF-I levels between controls and patients, with higher values in patients with active acne (Table 1).

Table 1.

The difference in serum survivin and serum IGF-I levels between controls and patients.

| Variables | Case group (n = 30) |

Control group (n = 30) |

P value | Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active acne (n = 15) |

Post-acne scar (n = 15) |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Survivin (pg/mL) | 38.1 | 11.4 | 35.7 | 14.8 | 26.4 | 4.8 | 0.9 a 0.002 b 0.01 c |

NS HS HS |

| IGF-I (ug/L) | 19.3 | 5.9 | 20.9 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 1.8 | 0.9 a 0.005 b <0.001 c |

NS HS HS |

NS, non-significant; HS, highly significant.

Women in the active acne group had significantly higher serum IGF-I, while the survivin level was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serum IGF-I and survivin level according to gender.

| Variables | Male |

Female |

P value | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Post-acne scar | ||||||

| Survivin (pg/mL) | 34.9 | 15.1 | 36.1 | 15.4 | 0.8 | NS |

| Active acne | ||||||

| Survivin (pg/mL) | 39.3 | 16.6 | 37.7 | 10.7 | 0.8 | NS |

| Controls | ||||||

| Survivin (pg/mL) | 26.5 | 3.1 | 26.4 | 5.4 | 0.9 | NS |

| Post-acne scar | ||||||

| IGF-I (ug/L) | 22.9 | 8.5 | 20.2 | 11.4 | 0.6 | NS |

| Active acne | ||||||

| IGF-I (ug/L) | 11.3 | 1.1 | 21.3 | 4.7 | 0.003 | HS |

| Controls | ||||||

| IGF-I (ug/L) | 12.6 | 1.5 | 12.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | NS |

NS, non-significant; HS, highly significant.

Positive correlation was found between disease severity and serum survivin levels in patients with active acne. However, there was no correlation between serum IGF-I levels and disease severity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of serum IGF-I levels among cases as regards disease severity degrees.

| Disease severity degrees | IGF-I (ug/L) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case group (n = 30) | ||||

| Active acne (n = 15) |

Post-acne scar (n=15) |

|||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Mild | 22.6 | 6.2 | 23.6 | 7.8 |

| Moderate | 16.8 | 6.1 | 19.2 | 12.7 |

| Sever | 18.5 | 4.7 | 19 | 0 |

| P value | 0.3 | 0.7 | ||

| Significance | NS | NS | ||

NS, non-significant.

There was a positive correlation between surviving and serum IGF-I levels and BMI in patients with post-acne scar. However, there was no statistically significant correlation between survivin level and any of age, BMI or disease duration among active acne patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

The correlation between survivin and serum IGF-I levels in in acne and post acne scar patients according to age, BMI, and disease duration among active acne patients.

| Case group (n = 30) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active acne (n = 15) |

Post-acne scar (n = 15) |

|||||

| Correlation (r value) | P value* | Significance | Correlation (r value) | P value | Significance | |

| Survivin (pg/mL) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 0.37 | 0.2 | NS | 0.3 | 0.2 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.06 | 0.8 | NS | 0.55 | 0.02 | S |

| Disease duration (years) | 0.4 | 0.1 | NS | 0.47 | 0.06 | NS |

| IGF-I (ug/L) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 0.17 | 0.6 | NS | −0.26 | 0.3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.38 | 0.2 | NS | 0.54 | 0.02 | S |

| Disease duration (years) | −0.39 | 0.2 | NS | 0.08 | 0.7 | NS |

P value < 0.05 is statistically significant.

NS, non-significant; S, significant.

There was no linear correlation between serum levels of survivin and IGF-I (Table 5).

Table 5.

The correlation between serum levels of survivin and IGF-1.

| Variable | Survivin (pg/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation (r value) | P value | Significance | |

| IGF-I (ug/L) | 0.22 | 0.2 | NS |

Discussion

Our results showed significantly high serum survivin levels between the control group and active acne and post-acne scar groups with higher values in the active acne patients; there was no significant difference in the level of survivin between the active acne and post-acne scar patients with significant increased levels with increased severity of acne and increased BMI in patients with post-acne scar. This could be explained by increased survivin levels leads to increased abnormal apoptosis that affects sebocyte survival, sebum production.7

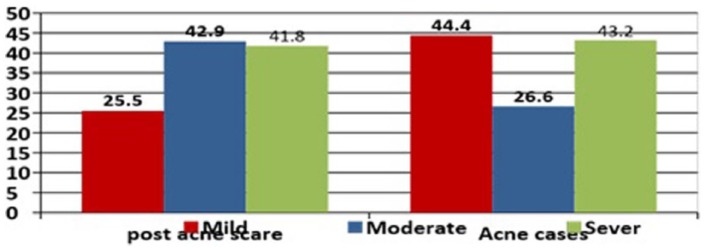

Studies exploring a relationship between serum survivin and active acne and post-acne scar are lacking. Only one prior study has shown a link between them.14 The authors found significantly higher serum levels of survivin in patients with active acne and in post-acne scar than the controls. However, unlike us, they found that patients with acne scar attained a higher level of survivin than patients with active acne (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean values of serum survivin in different disease degrees among case group; in cases of post acne scar, patients with moderate and severe degree have higher levels of survivin than mild degree, while in patients with acne, patients with mild and severe degree have higher levels of survivin than moderate.

In our study, we additionally evaluated the serum levels of IGF-I. Patients with active acne and post-acne scar had significantly higher levels than the controls regardless of disease severity. It could be argued that the increased levels of IGF-I increase lipogenesis by activating PI3K/Akt pathways and MAPK/ERK signal transduction and induction of SREBP-1, which is responsible for fatty acid synthesis genes regulation.9 Similar data were found in other studies.14–19 However, in our study we found no correlation between disease severity and level of IGF-1. This could be due to the use of different grading system to classify disease severity.

On the contrary, Kaymak et al.20 found no significant difference in serum glucose, IGF-I and leptin levels was observed between acne patients and control individuals.

In our patients, there was a significant correlation between IGF-I level and BMI only in patients with post-acne scar. This is possibly due to delayed wound healing caused by obesity and the over-scarring process due to increased TGF-B.21

These results were in agreement with another study by Rietveld et al.;22 They reported that there were no significant differences in mean serum total IGF-I, BMI and body height in active acne patients.

An inverse relation between IGF-I and BMI, body weight and waist circumference were recorded in many studies.12,18,23,24

The present study showed that women had a significantly higher difference in IGF-I levels than men among the patients with acne and the controls. Similar data were found in other studies.25,26 This could be due to hormonal differences;7 however, no difference was reported by El-Tahlawi et al.15

The present study showed that there was no statistically significant difference in IGF-I levels regarding patient age, family history and disease duration among acne patients.

The current study also showed that there was no statistically significant correlation between serum levels of survivin and IGF-I. However, Assaf et al.14 found a significant correlation between IGF-I and survivin levels and they explained their data by the fact that the increased IGF-I signalling is related to the enhanced survivin expression by IGF-I/PI3K-/AKT. These results may refer to the small number of patients involved in our study; therefore, large-scale studies are needed to further elaborate the relation between survivin and IGF-I in acne and acne scar.

In conclusion, the increased serum levels of survivin and IGF-I in patients with acne vulgaris and post-inflammatory acne scar compared to controls draws attention to their possible role in the pathogenesis of them. However, further studies on a larger scale are required to elaborate the relation between survivin and IGF-I.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Rahaman SMA, De D, Handa S, et al. Association of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 gene polymorphisms with plasma levels of IGF-1 and acne severity. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75(4): 768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alper M, Khurami FA. Histopathologic evaluation of acneiform eruptions: practical algorithmic proposal for acne lesions. In: Kartal SP, Gonul M. (eds) Acne and Acneiform Eruptions. InTech 2017; 139–160. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/acne-and-acneiform-eruptions/histopathologic-evaluation-of-acneiform-eruptions-practical-algorithmic-proposal-for-acne-lesions.

- 3. Wu NL, Lee TA, Tsai TL, et al. TRAIL-induced keratinocyte differentiation requires caspase activation and p63 expression. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131(4): 874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan Z, Bhadouria P, Gupta R, et al. Tumor control by manipulation of the human anti-apoptotic survivin gene. Curr Cancer Ther Rev 2006; 2(1): 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Altieri DC. Survivin - The inconvenient IAP. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015; 39: 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nigam J, Chandra A, Kazmi HR, et al. Expression of survivin mRNA in gallbladder cancer: a diagnostic and prognostic marker. Tumour Biol 2014; 35(9): 9241–9246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Webb JB, Hardin AS. A preliminary evaluation of BMI status in moderating changes in body composition and eating behavior in ethnically-diverse first-year college women. Eat Behav 2012; 13(4): 402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keating GM. Mecasermin. Bio Drugs 2008; 22(3): 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Melnik BC, Schmitz G. Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food andmilk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Exp Dermatol 2009; 18(10): 833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsurutani Y, Fujimoto M, Takemoto M, et al. The roles of transforming growth factor-β and Smad3 signaling in adipocyte differentiation and obesity. Biochem Biophysic Res Comm 2011; 407(1): 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Well D. Acne vulgaris: A review of causes and treatment options. Nurse Pract 2013; 38(10): 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seleit I, Bakry OA, Abdou AG, et al. Body mass index, selected dietary factors, and acne severity: are they related to in situ expression of insulin-like growth factor-1. Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol 2014; 36(5): 267–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg 2006; 32(12): 1458–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Assaf HA, Abdel-Maged WM, Elsadek BE, et al. Survivin as a novel biomarker in the pathogenesisof acne vulgaris and its correlation to insulin-like growth factor-I. Dis Markers 2016; 2016: 7040312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El-Tahlawi SM, Abdel-Halim MR, Hamid MFA, et al. Gene polymorphism and serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-I in Egyptian acne patients. J Egy Women’s Dermatol Society 2014; 11(1): 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agamia NF, Abdallah DM, Sorour O, et al. Skin expression of mammalian target of rapamycin and forkhead box transcription factor O1, and serum insulin-like growth factor-I in patients with acne vulgaris and their relationship with diet. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174(6): 1299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rietveld I, Janssen JA, Hofman A, et al. A polymorphism in the IGF-I gene influences the age-related decline in circulating total IGF-I levels. Eur J Endocrinol 2003; 148(2): 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saleh NF, Ramadan SA, Zeid OMA, et al. Role of diet in acne: a descriptive study. J Egy Women’s Dermatol Soc 2011; 8(2): 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsai CH, Yang SF, Chen YJ, et al. The upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 in oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol 2005; 41(9): 940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaymak Y, Adisen E, Ilter N, et al. Dietary glycemic index and glucose, insulin, insulin like growth factor-1, insulin like growth factor binding protein 3 and leptin levels in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57(5): 819–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim JH, Sung JY, Kim YH, et al. Risk factors for hypertrophic surgical scar development after thyroidectomy. Wound Repair Regen 2012; 20(3): 304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rudman SM, Philpott MP, Thomas GA, et al. The role of IGF-I in human skin and its appendages: morphogen as well as mitogen? J Invest Dermatol 1997; 109(6): 770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morimoto LM, Newcomb PA, White E, et al. Variation in plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3: personal and lifestyle factors (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2005; 16(8): 917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74(5): 945–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aizawa H, Niimura M. Elevated serum insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) levels in women with postadolescent acne. J Dermatol 1995; 22(4): 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cappel M, Mauger D, Thiboutot D. Correlation between serum levels of insulin like growth factor-1, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and dihydrotestosterone and acne lesion counts in adult women. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141(3): 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

How to cite this article

- El-Tahlawi S, Mohammad NE, El-Amir AM, Mohamed HS. Survivin and insulin-like growth factor-I: potential role in the pathogenesis of acne and post-acne scar. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 5, 2019. DOI: 10.1177/2059513118818031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]