Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

The aim of this study was to prospectively and longitudinally investigate maternal iron status during early to mid-pregnancy, and subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), using a comprehensive panel of conventional and novel iron biomarkers.

Methods

A case-control study of 107 women with GDM and 214 controls (matched on age, race/ethnicity, and gestational week of blood collection) was conducted within the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort (2009–2013), a prospective and multiracial pregnancy cohort. Plasma hepcidin, ferritin, and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) were measured, and sTfR:ferritin ratio was derived, twice before GDM diagnosis (gestational weeks 10–14 and 15–26), and at weeks 23–31 and 33–39. GDM diagnosis was ascertained from medical records. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for GDM were estimated using conditional logistic regression adjusting for demographics, pre-pregnancy BMI, and other major risk factors.

Results

Hepcidin concentrations during weeks 15–26 were 16% significantly higher among GDM cases than controls (median 6.4 vs. 5.5 ng/ml), and positively associated with GDM risk; aOR (95% CI) comparing highest vs. lowest quartile was 2.61(1.07, 6.36). Ferritin levels were positively associated with GDM risk; aOR (95% CI) comparing the highest vs. lowest quartile was 2.43 (1.12, 5.28) and 3.95 (1.38, 11.30) at weeks 10–14 and 15–26. The sTfR:ferritin ratio was inversely related to GDM risk; aOR (95% CI) for highest vs. lowest quartile was 0.33 (0.14, 0.80) at weeks 10–14 and 0.15 (0.05, 0.48) at weeks 15–26.

Conclusions/interpretation

Our findings suggest that elevated iron stores may be involved in the development of GDM from as early as the first trimester. This raises potential concerns for the recommendation of routine iron supplementation among iron-replete pregnant women.

Keywords: Ferritin, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Hepcidin, Iron Overload, Soluble transferrin receptor, sTfR:ferritin ratio

INTRODUCTION

Iron is regarded as a double-edged sword in living systems, as both iron deficiency and overload can be harmful. Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to iron deficiency and related adverse pregnancy outcomes [1]. While a few guidelines, including those from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommend screening and treatment for iron deficiency as required, several other groups, such as the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommend routine iron supplementation in pregnant women [2]. Emerging findings from both animal and human studies, however, have raised critical concerns about significant links between larger iron stores and disturbances in glucose metabolism, including increased risk of type 2 diabetes among non-pregnant individuals [3–5]. The evidence is unclear regarding the contribution of larger iron stores in pregnancy to the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), a common complication of pregnancy that is associated with a number of adverse health outcomes for both women and their children [6]. Advancing gestation is characterized by progressive increases in demands for iron [6] and insulin resistance [7], the latter being a central feature of GDM. Longitudinal studies that examine iron status across pregnancy are, hence, needed to comprehensively elucidate the role of iron status in the pathogenesis of GDM.

Prospective studies investigating the association between iron status in pregnancy and the risk of GDM are few and inconsistent in their findings [8–12], and none have examined these associations with longitudinal measurements of iron status. In addition, the vast majority of the existing literature centers on serum ferritin as a biomarker of iron stores. Ferritin levels, however, may not be the optimal indicator of iron status, as they may also increase in the presence of infection or inflammation [13]. Alternatively, soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), a marker of tissue iron insufficiency, could provide useful and complementary information on iron status as it considered to be less influenced by the acute phase response than ferritin [13–15]. Furthermore, emerging evidence has identified hepcidin, a novel biomarker, as the master regulator of iron homeostasis [16]. In response to high body iron stores, increased hepatic secretion of hepcidin inhibits iron absorption from three main sources: dietary absorption in the gut, recycled iron from macrophages, and stored iron released from hepatocytes [16]. In pregnancy, hepcidin may also play a critical role in the active transport of iron to the fetus [17]. To our knowledge, only one prior study has examined serum hepcidin levels in relation to GDM [18]. The study found a positive association, yet provided limited inference because of the small number of GDM cases (n=30), cross-sectional analysis with blood samples collected at the same time as GDM diagnosis, and lack of adjustment for potential confounders.

In the present study, we aimed to prospectively and longitudinally investigate body iron status during early to mid-pregnancy and its association with subsequent GDM risk, using a comprehensive panel of conventional and novel iron biomarkers including hepcidin, ferritin, sTfR, and sTfR:ferritin ratio. Additionally, concurrent measurements of plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were obtained to account for inflammation. The secondary objective of the study was to characterize longitudinal changes in these iron metabolism biomarkers throughout pregnancy.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a case-control study within the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies –Singleton Cohort (2009–2013), which was a prospective and multiracial pregnancy cohort. Briefly, 2,334 non-obese [19] and 468 obese women, aged 18–40 years, were recruited between 8 and13 weeks of gestation, from 12 U.S. clinical centers, and followed throughout pregnancy. Eligible women had a known date of last menstrual period (LMP), which was confirmed by ultrasound screening at enrolment. Women whose LMP and ultrasound dates did not match within a specific range (± 5–7 days) were excluded from the study. Women with a history of pre-existing hypertension, diabetes, or other major chronic diseases were also excluded. Research approval was obtained from all participating institutions; women provided written informed consents.

In the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies singleton Cohort, 107 women with GDM (cases) were identified by medical record review. The GDM diagnosis was based on the Carpenter and Coustan’s diagnostic criteria [20]. Each case was matched with two randomly-selected non-GDM controls, based on age (± 2 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander), and gestational week of blood collection (± 2 weeks). Thus, a total of 321 women (107 GDM cases and 214 non-GDM controls) from the original cohort were included in this case-control study. Following a standardised protocol, blood specimens were collected at four study visits during pregnancy. The visits were targeted at gestational weeks 8–13 (enrolment), 16–22, 24–29, and 34–37, but the actual ranges were gestational weeks 10–14, 15–26, 23–31, and 33–39, respectively. Blood specimens collected at the second visit (weeks 15–26) were collected after an overnight fast. All biospecimens were immediately processed and stored at −80°C until beng thawed for laboratory analysis.

Exposure assessment

Concentrations of plasma hepcidin levels (ng/ml) were measured using a competitive binding ELISA kit [Human Hepcidin-25 (bioactive) ELISA kit; DRG Diagnostics Marburg, Germany]. Concentrations of plasma ferritin (pmol/l) and sTfR (nmol/l) were measured using Roche reagents on the Roche Modular P chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). sTfR:ferritin ratio was derived by dividing the plasma concentration of sTfR (ug/l) by that of ferritin (ug/l). Plasma CRP (nmol/l) was measured using a highly sensitive latex-particle- enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay kit) on the Roche Modular P Chemistry analyzer. All assays were performed blinded to case or control status and the inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were ≤13%. For the GDM cases and one of their matched controls, the assays were performed using sample from all four time points of blood collection. With the remaining control participants, biomarkers were only measured with the blood specimens collected at the two visits prior to GDM diagnosis (i.e. gestational weeks 10–14 and 15–26).

Assessment of Covariates

A structured questionnaire administered at enrolment and collected information on several GDM risk factors, including maternal age (years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander), nulliparity (yes/no), family history of diabetes (yes/no), education (less, equal to, or more than high-school), smoking in the 6 months preceding pregnancy (yes/no), and alcohol consumption in the3 months preceding pregnancy (yes/no). Pre-pregnancy BMI (<25, 25.0–29.9, ≥30.0 kg/m2) was calculated from pre-pregnancy weight (self-reported) and height (measured at enrollment). Information on GDM treatment (diet/lifestyle modification/medication) was obtained by reviewing medical records. Gestational age (weeks) at each blood collection was calculated from the reported LMP date. At each study visit, women also reported medication and supplement use, including iron supplements.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean (SD) for parametric continuous variables, median (25th, 75th percentile) for non-parametric continuous variables, and frequencies for categorical variables. Differences between cases and controls were analysed using generalised linear mixed effects models for continuous variables and binomial/multinomial logistic regression with generalised estimating equations for categorical variables, accounting for matched case-control pairs. To examine the longitudinal trajectory of each iron biomarker over pregnancy, median concentrations of the biomarkers were plotted by study visit.

For each iron marker, crude and adjusted quartile-specific ORs of GDM were estimated at weeks 10–14 and 15–26 (visits prior to the typical screening for GDM) from conditional logistic regression models with the lowest quartile as the reference group. The multivariable models were adjusted for a priori selected covariates including parity, education, family history of diabetes, and pre-pregnancy BMI. Since maternal age and gestational age at blood collection were matched between cases and controls only within a specified range, both were included as covariates to derive conservative risk estimates. Additionally, we adjusted for CRP levels at the corresponding visit to limit the potential influence of inflammation status. Tests of linear trend were conducted by using the median value for each quartile and fitting it as a continuous variable in the conditional logistic regression models. We excluded one case at weeks 10–14 and five at weeks 15–26 from the final analyses, as they were diagnosed with GDM before the respective visit.

In order to test the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding women with a history of GDM (n=6), a history of chronic anemia and other hematologic disorders (n=2), smoking before the current pregnancy (n=5), self-reported anaemia during the current pregnancy (n=16), or suspected iron deficiency (defined as plasma ferritin <26.9 pmol/l [9] ) at weeks 10–14 (n=3) or 15–26 (n=13). To evaluate whether the findings were modified by major risk factors of GDM, we also conducted stratified analyses by pre-pregnancy obesity status (BMI < 30.0 vs. BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2), median CRP level (<48.3 vs ≥48.3 nmol/l at weeks 10–14 and <49.5 vs ≥49.5 nmol/l at weeks 15–26), family history of diabetes (yes vs. no), and GDM severity as indicated by treatment (diet/lifestyle modification vs. medication use). Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significance criterion was set at two-tailed p values <0.05.

RESULTS

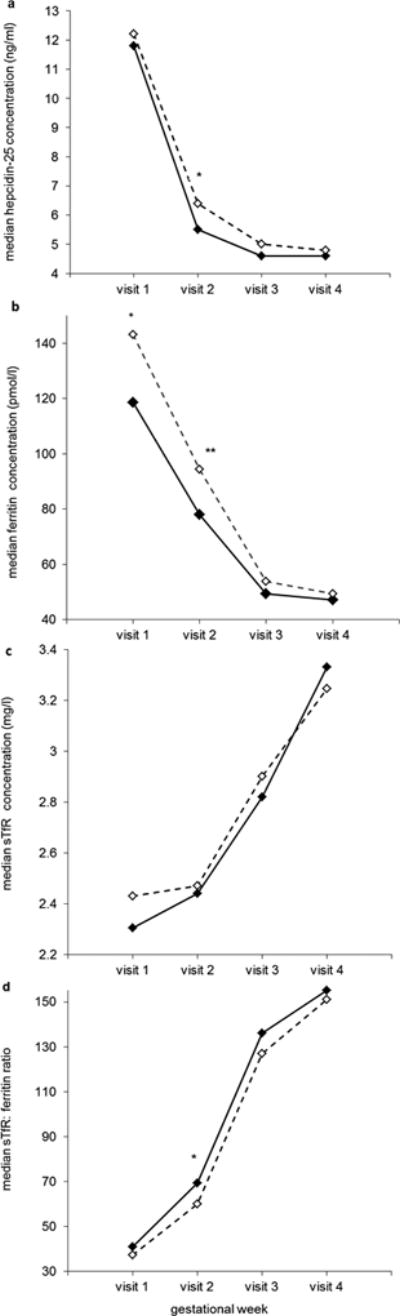

Compared with non-GDM controls, women who subsequently developed GDM were more likely to have a higher pre-pregnancy BMI and a family history of diabetes (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the longitudinal trajectory of each iron biomarker among women with GDM and their matched controls. Hepcidin and ferritin concentrations tended to decline through mid-pregnancy and then level off. In comparison, sTfR concentrations and the sTfR:ferritin ratio, both indicators of iron insufficiency, tended to increase with the progression of pregnancy.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics among women with gestational diabetes and their matched controls in the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort (2009–2013)

| GDM Cases (n = 107) |

Non-GDM controls (n = 214) |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.5 ± 5.7 | 30.4 ± 5.4 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 25 (23.4) | 50 (23.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15 (14.0) | 30 (14.0) | |

| Hispanic | 41 (38.3) | 82 (38.3) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 26 (24.3) | 52 (24.3) | |

| Education | 0.18 | ||

| Less than high school | 17 (15.9) | 26 (12.1) | |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 15 (14.0) | 23 (10.7) | |

| More than high school | 75 (70.1) | 165 (77.1) | |

| Married/living with a partner | 92 (86.0) | 167 (78.0) | 0.12 |

| Nulliparity | 48 (44.9) | 96 (44.9) | 1 |

| Family history of diabetes | 40 (38.8) | 48 (22.6) | 0.003 |

| Anemia during pregnancy and before GDM diagnosis | 6 (5.6) | 11 (5.1) | 0.85 |

| Smoked before pregnancy a | 4 (3.7) | 1 (0.5) | 0.06 |

| Alcoholic beverage consumption before pregnancy | 61 (57.0) | 137 (64.0) | 0.22 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | ||

| 18.38 – 24.99 | 37 (34.6) | 123 (58.0) | |

| 25.0 – 29.99 | 35 (32.7) | 56 (26.4) | |

| 30.0 – 45.11 | 35 (32.7) | 33 (15.6) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes.

Data are presented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean (SD) for continuous variables.

p values for differences between cases and controls were obtained by generalized linear mixed effects models for continuous variables and binomial/multinomial logistic regression with generalized estimating equations for binary/multilevel categorical variables, accounting for matched case-control pairs. p values are not shown for matching variables (age, race/ethnicity).

Non-obese women who smoked were not eligible for the study.

Figure 1.

Median plasma concentrations of hepcidin (a), ferritin (b), soluble transferrin receptor (c), and sTfR:ferritin ratio (d) at each study visit among women with gestational diabetes and their matched controls.

Solid line with black diamonds, non-GDM controls; dashed line with white diamonds, GDM cases.

Visit 1 (weeks 10–14): n = 104 and 214 for cases and controls, respectively; Visit 2 (weeks 15–26): n = 94 and 212 for cases and controls, respectively; Visit 3 (weeks 23–31): n = 102 and 106 for cases and controls, respectively; Visit 4 (weeks 33–39): n = 88 and 101 for cases and controls, respectively.

*P <0.05, **P <0.01 for case-control comparisons at each study visit obtained by generalized linear mixed effects models accounting for matched case-control pairs.

Abbreviations: GDM, gestational diabetes; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor.

At the first visit (weeks 10–14), only ferritin levels differed significantly between GDM cases and controls. Ferritin levels were approximately 21% higher among women who subsequently developed GDM than those who did not (Table 2; median levels 143.2 vs. 118.7 pmol/l, p=0.04). At weeks 15–26, closer to the time of GDM diagnosis, both hepcidin and ferritin levels were significantly higher among cases than controls. In addition, the sTfR:ferritin ratio was lower among cases at both visits, but the difference was statistically significant only at the second visit. sTfR concentrations did not differ significantly between GDM cases and controls at either visit.

Table 2.

Median plasma concentrations of iron biomarkers among women with gestational diabetes and their matched controls in the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort (2009–2013)

| GDM Cases | Non-GDM controls | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational weeks 10 – 14 (first visit) a | |||

| Hepcidin ( ng/ml) | 12.2 (8.3 – 21.4) | 11.8 (7.0 – 18.7) | 0.20 |

| Ferritin (pmol//l) | 143.2 (92.0 – 206.2) | 118.7 (76.8 – 173.9) | 0.04 |

| Soluble Transferrin Receptor (nmol/l) | 28.2 (22.3 – 34.1) | 27.1 (22.3 – 34.1) | 0.63 |

| sTfR:ferritin ratio c | 37.3 (26.0 – 61.9) | 40.9 (27.6 – 77.8) | 0.14 |

| Gestational age at blood collection, (weeks) | 13.0 (12.3 – 13.6) | 13.0 (12.4 – 13.6) | |

| Gestational weeks 15–26 (second visit) b | |||

| Hepcidin ( ng/ml) | 6.4 (4.6 – 8.3) | 5.5 (4.0 – 7.9) | 0.02 |

| Ferritin (pmol/l) | 94.5 (67.9 – 133.5) | 78.1 (49.7 – 119.4) | 0.007 |

| Soluble Transferrin Receptor (nmol/l) | 29.4 (24.7 – 35.3) | 28.2 (24.7 – 35.3) | 0.85 |

| sTfR:ferritin ratio c | 60.0 (36.9 – 85.4) | 69.4 (40.6 – 130.9) | 0.02 |

| Gestational age at blood collection (weeks) | 18.9 (17.3 – 21.0) | 19.0 (17.7 – 21.1) | |

Abbreviations: GDM, gestational diabetes.

Data are presented as median (25th and 75th percentile).

p values for differences between cases and controls were obtained by generalized linear mixed effects models for continuous variables accounting for matched case-control pairs. p values are not shown for gestational age at blood collection as it was one of the matching variables.

n = 104 and 214 for cases and controls, respectively.

n = 94 and 212 for cases and controls, respectively;

sTfR:ferritin ratio was obtained by dividing plasma concentration of soluble transferrin receptor (ug/l) by plasma ferritin level (ug/l).

Associations between quartiles of iron biomarker and GDM status are shown in Table 3. During gestational weeks 10–14, ferritin levels were significantly and positively associated with GDM risk; aOR (95% CI) comparing the highest vs. lowest quartile was 2.43 (1.12, 5.28). The odds of GDM tended to increase with increasing quartiles of ferritin at weeks 10–14 (p for trend=0.03). In comparison, the sTfR:ferritin was significantly and inversely associated with GDM risk at weeks 10–14 (p for trend=0.02), with an aOR (95% CI) of 0.33 (0.14, 0.80) when comparing the highest vs. lowest quartile (Table 3). At 15–26 weeks, plasma concentrations of hepcidin and ferritin were significantly and positively associated with GDM risk, whereas sTfR:ferritin ratio was inversely related to GDM risk (Table 3). Specifically, comparing the highest with the lowest quartile, aOR (95% CI) associated with GDM risk was 2.61 (1.07, 6.36) for hepcidin, 3.95 (1.38, 11.3) for ferritin, and 0.15 (0.05, 0.48) for sTfR:ferritin ratio. The test for linear trend was only significant for sTfR:ferritin ratio (p for trend=0.002).The associations between iron biomarkers and GDM risk remained practically unchanged between multivariable models with and without additional adjustment for CRP levels (Table 3; data not shown for the latter).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) for GDM according to quartiles of hepcidin, ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, and sTfR:ferritin ratio at gestational weeks 10–14 and 15–26, the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort (2009–2013)

| Case n |

Control n | Crude model | Multivariable model a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational weeks 10–14 b | ||||

| Hepcidin (ng/ml) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 6.97 | 21 | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 6.98 – 11.80 | 29 | 52 | 1.38 (0.73, 2.61) | 1.12 (0.54, 2.32) |

| Quartile 3: 11.81 – 18.70 | 25 | 53 | 1.19 (0.57, 2.46) | 0.87 (0.38, 1.99) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 18.71 | 28 | 52 | 1.32 (0.66, 2.67) | 1.11 (0.51, 2.44) |

| Ferritin (pmol/l) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 77.05 | 18 | 54 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 77.06 – 118.7 | 23 | 53 | 1.36 (0.65, 2.84) | 1.57 (0.69, 3.56) |

| Quartile 3: 118.8– 173.9 | 26 | 54 | 1.57 (0.75, 3.27) | 1.71 (0.75, 3.90) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 174.0 | 37 | 53 | 2.11 (1.06, 4.20) | 2.43 (1.12, 5.28) |

| Soluble Transferrin Receptor (nmol/l) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 22.3 | 24 | 54 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 22.4– 27.1 | 23 | 53 | 0.94 (0.47, 1.90) | 0.99 (0.45, 2.17) |

| Quartile 3: 27.2 – 33.8 | 29 | 54 | 1.21 (0.63, 2.35) | 0.89 (0.41, 1.91) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 33.9 | 28 | 53 | 1.23 (0.62, 2.46) | 1.00 (0.45, 2.20) |

| sTfR:ferritin ratioc | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 27.65 | 32 | 54 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 27.66 – 40.90 | 26 | 53 | 0.83 (0.44, 1.57) | 0.67 (0.32, 1.42) |

| Quartile 3: 40.91 – 77.83 | 31 | 54 | 0.97 (0.51, 1.83) | 0.88 (0.43, 1.81) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 77.84 | 15 | 53 | 0.47 (0.22, 1.00) | 0.33 (0.14, 0.80) |

| Gestational weeks 15–26 b | ||||

| Hepcidin (ng/ml) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 4.00 | 14 | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 4.01 – 5.46 | 19 | 53 | 1.63 (0.71, 3.77) | 1.49 (0.57, 3.93) |

| Quartile 3: 5.47 – 7.91 | 30 | 53 | 2.27 (1.01, 5.11) | 2.97 (1.16, 7.60) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 7.92 | 31 | 52 | 2.40 (1.08, 5.35) | 2.61 (1.07, 6.36) |

| Ferritin ( pmol/l) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 49.6 | 10 | 54 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 49.7 – 77.9 | 28 | 52 | 2.76 (1.20, 6.33) | 4.45 (1.61, 12.3) |

| Quartile 3: 78.0 – 119.3 | 26 | 53 | 2.59 (1.11, 6.03) | 3.42 (1.26, 9.30) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 119.4 | 30 | 53 | 3.06 (1.27, 7.34) | 3.95 (1.38, 11.3) |

| Soluble Transferrin Receptor (nmol/l) | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 24.2 | 23 | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 24.3 – 28.7 | 21 | 54 | 0.87 (0.43, 1.76) | 0.89 (0.39, 2.04) |

| Quartile 3: 28.8 – 34.9 | 24 | 53 | 1.08 (0.51, 2.29) | 1.31 (0.55, 3.09) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 35.0 | 26 | 52 | 1.23 (0.56, 2.67) | 1.17 (0.49, 2.82) |

| sTfR:ferritin ratio c | ||||

| Quartile 1: ≤ 40.40 | 31 | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| Quartile 2: 40.41 – 69.36 | 23 | 53 | 0.66 (0.31, 1.37) | 0.58 (0.25, 1.33) |

| Quartile 3: 69.37 – 130.87 | 32 | 53 | 1.07 (0.51, 2.23) | 1.14 (0.49, 2.65) |

| Quartile 4: ≥ 130.88 | 8 | 53 | 0.25 (0.10, 0.64) | 0.15 (0.05, 0.48) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes.

Adjusted for maternal age (years), gestational age at blood collection (weeks), parity (nulliparous or not), education (less, equal to or more than high-school) family history of diabetes (yes/no), pre-pregnancy body mass index (< 25, 25.0–29.9, ≥30.0 kg/m2), and plasma C-reactive protein levels.

Timing of blood sample collection preceded the diagnosis of gestational diabetes in all participants.

sTfR:ferritin ratio was obtained by dividing plasma concentration of Soluble Transferrin Receptor (ug/l) by plasma ferritin level (ug/l).

The majority of women in our study (83% at weeks 10–14; 87% in the second trimester during 15–26 gestational weeks) reported using supplemental iron, including both iron-only supplements as well as prenatal or standard multivitamins that contained iron (data not shown). In sensitivity analyses (data not shown), the associations between iron biomarkers and GDM risk were attenuated, but did not appreciably change after additional adjustment for supplemental use of iron (yes/no) at the corresponding visit. The associations also persisted in sensitivity analyses after the exclusion of women with a history of prior GDM, self-reported anemia during pregnancy, smoking before pregnancy, suspected iron deficiency (plasma ferritin <26.9 pmol/l [9]), or history of chronic anemia and other hematologic disorders. Additionally, the directions of the associations remained similar when stratifying the analyses by pre-pregnancy obesity status, CRP level, family history of diabetes, or severity of GDM (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective, longitudinal study of pregnant women without pre-pregnancy chronic diseases, higher iron status in pregnancy (as indicated by higher hepicidin and ferritin concentrations and a lower sTfR:ferritin ratio) was significantly associated with an elevated GDM risk, even after adjustment for plasma CRP levels, pre-pregnancy BMI, and other major GDM risk factors. Additionally, the magnitude of associations appeared greater in the second trimester, closer to GDM diagnosis, than in early pregnancy.

Among iron biomarkers, ferritin has been most often investigated in relation to GDM. Our finding of a significant and positive association between ferritin levels and GDM was consistent with most [9–12, 18, 21–26], but not all previous studies [8, 27, 28]. Notably, the majority of the prior studies were cross-sectional using only a single measurement of ferritin, typically assessed at the time of GDM diagnosis [18, 21–27]. Peripheral circulating ferritin concentrations are a good proxy for body iron stores, yet being an acute phase reactant, ferritin levels may also increase due to subclinical systemic inflammation, which is associated with insulin resistance in GDM [13]. Hence, prospective studies that measure iron status well before GDM diagnosis are needed to establish temporality and to control for confounding by insulin resistance-mediated inflammation. Studies that have prospectively examined the association of ferritin with GDM risk have, however, been limited and inconsistent in their findings [8–12]. For instance, a study based in Lebanon [8] found that high ferritin in early pregnancy was significantly associated with impaired glucose tolerance but not with GDM incidence, although the latter could be attributed to the small number of GDM cases in the study (n=16). In another prospective study [11], the association between serum ferritin and GDM was significant after accounting for several confounders, including ethnicity and family history of diabetes, but was attenuated to non-significance after additionally accounting for pre-pregnancy BMI. On the other hand, a recent case-control study [12] based on data from the Danish National Birth Cohort (1996–2002) reported a positive and significant association between ferritin and GDM risk, even after adjustment for plasma CRP levels and several risk factors of GDM including pre-pregnancy BMI. Similar to the Danish study [12], we minimised the influence of inflammatory status by controlling for CRP levels in our multivariable models and found that high ferritin was significantly associated with GDM risk at as early as 10–14 weeks of gestation. Our study offers several unique strengths compared to the Danish study [12], including a longitudinal design with two iron measurements prior to GDM diagnosis, a more contemporary and multiracial cohort, and the evaluation of hepcidin, a relatively novel biomarker recently identified to be the master regulator of iron homeostasis. Only one prior study has been carried out to examine hepicidin levels in relation to GDM [18]; in this study, positive associations were observed between hepcidin and GDM, similar to our study. However, inferences that can be drawn from the findings of this prior study are hindered by its cross-sectional examination of the data [18]. More importantly, the study did not control for potential confounding factors or account for the impact of inflammation status.

sTfR, a marker of tissue iron insufficiency, also has been under-studied in the context of risk for GDM [9, 12, 29]. In the present study, no significant association was observed between sTfR levels and GDM risk. Similarly, in an Australian cohort of pregnant women, first trimester levels of sTfR were not found to be significantly associated with the risk of GDM [9, 29]. In a recent study conducted among Danish women [12], sTfR concentrations in early pregnancy (9.4 ± 3.2 weeks of gestation) were significantly and positively associated with GDM risk, but this was attenuated to non-significance after adjustment for pre-pregnancy BMI. It is worth noting, however, that sTfR levels tend to increase only in the presence of a functional iron deficiency. In an experimental study [14] in which iron-deficiency anaemia was gradually induced in healthy participants, serum ferritin levels declined as iron stores decreased, whereas circulating sTfR levels increased only once the iron stores had been significantly depleted. In our study sample, there were only a small number of women with suspected iron deficiency (three women at weeks 10–14 and 13 women at 15–26 women), as defined by plasma ferritin levels less than 26.9 pmol/l [9]. Hence, the sTfR levels alone might not have been an appropriate indicator of iron status in our sample.

Our study is unique in that we further examined the sTfR:ferritin ratio, a measure that captures both cellular iron cellular iron demand and the availability of body iron stores [14]. The added value of using sTfR:ferritin ratio, as opposed to isolated measurements of sTfR and ferritin, is that it covers the full spectrum of iron homeostasis, from normal, healthy iron stores to mild or substantial functional iron deficiency [14, 15]. The sTfR:ferritin ratio offers greater sensitivity and specificity in characterizing iron status than individual measurements of ferritin and sTfR, and is considered to be particularly useful when the use of individual measurements yield ambiguous results [13]. In the present study, we observed significant inverse associations between sTfR:ferritin ratio and GDM, despite having observed no association with sTfR levels alone. This suggests that the inverse association with sTfR:ferritin ratio may be driven primarily through ferritin, and hence this finding should be interpreted cautiously.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively demonstrate significant and positive associations between iron status during pregnancy and GDM risk using longitudinal measurements of a panel of conventional and novel iron biomarkers. Higher hepcidin levels, which indicate an iron surplus, were significantly related to an increased GDM risk only during the second trimester, before the diagnosis of GDM. Similarly, elevated second trimester iron status, whether based on higher ferritin levels or lower sTfR:ferritin ratio, was more strongly associated with GDM risk than an elevated first trimester iron status.

In secondary analyses, we examined the longitudinal trajectory of several iron biomarkers over the entire course of pregnancy. Hepcidin and ferritin concentrations tended to decline with advancing gestation, whereas sTfR concentrations and the sTfR:ferritin ratio, both indicators of iron insufficiency, tended to increase with the progression of pregnancy. This is expected as iron requirements increase dramatically across pregnancy in order to support placental and fetal growth, sustain the expansion of red blood cell mass, as well as to offset blood losses from delivery [30]. A similar decline in ferritin and hepcidin levels and an increase in sTfR concentrations through the course of pregnancy have been previously reported by others, yet our study is the largest to provide data for changes in hepcidin levels across pregnancy [31, 32].

Our findings are biologically plausible. Iron may play a role in the pathogenesis of GDM via several potential mechanisms. As a strong pro-oxidant, free iron can catalyze several cellular reactions that generate reactive oxygen species and increase the level of oxidative stress [3]. Oxidative stress induced from excess iron accumulation can cause β-cell damage and apoptosis, and consequently, contribute to impaired insulin synthesis and secretion [3]. In the liver, high iron stores may induce insulin resistance via impaired insulin signaling as well as by attenuating the capacity of the liver to extract insulin [33, 34]. Excess iron deposition in the muscles may enhance NEFA oxidation, and interfere with glucose uptake or disposal [33, 34]. Iron accumulation may also impair the action of insulin and interfere with insulin-induced glucose transport in adipocytes [33, 34]. Consistent with this notion, increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes has been observed in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder characterized by excessive iron absorption and pathological increases in total body iron stores [33]. Similarly, increasing evidence from biological and epidemiological studies show that elevated body iron stores are associated with an increased risk of types 1 and 2 diabetes [3–5]. Furthermore, induction of iron depletion has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity measures in carbohydrate-intolerant subjects [35, 36].

Our study had several strengths. First, the longitudinal blood collection provided a unique opportunity to prospectively investigate levels of iron biomarkers across pregnancy and their trimester-specific associations with subsequent risk of GDM. Second, the study participants represented various race/ethnicities and included a relatively high number of GDM cases that were well characterized based on medical records. More importantly, our study examined novel biomarkers in addition to conventional biomarkers of iron status, and measured them prospectively at multiple time points before GDM diagnosis. Finally, we considered the influence of a number of important confounding factors, including inflammatory status, in evaluating the relationship between iron status in pregnancy and GDM risk. It is important to note that the present study was focused on examining the role of body iron status, as measured by plasma iron biomarkers, in the development of GDM; future studies investigating how dietary iron intake influences these biomarkers and ultimately impacts GDM risk are warranted.

In summary, findings from this longitudinal and prospective study among multiracial, relatively healthy pregnant women without any pre-pregnancy chronic disease, suggest that higher maternal iron stores may play a role in the development of GDM from as early as the first trimester. These findings are of clinical and public health importance as they extend the observation of an association between high body iron stores and elevated risk of glucose intolerance among non-pregnant individuals to those who are pregnant, and raise potential concerns for the recommendation of routine iron supplementation among iron replete pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the research teams at our participating clinical centers, including Christina Care Health Systems; University of California, Irvine; Long Beach Memorial Medical Center; Northwestern University; Medical University of South Carolina; Columbia University; New York Hospital Queens; St Peters’ University Hospital; University of Alabama at Birmingham; Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island; Fountain Valley Regional Hospital and Medical Center; and Tufts University. We would also like to thank the C-TASC Corporation for providing data coordination, as well as the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota for providing laboratory support and resources needed for analysis of blood samples and biomarkers.

Some of the data from this study were presented as a poster at the 76th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, LA. June 10–14, 2016.

Funding: This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development intramural funding and included American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funding via contract numbers HHSN275200800013C, HHSN275200800002I, HHSN27500006, HHSN275200800003IC, HHSN275200800014C, HHSN275200800012C, HHSN275200800028C, and HHSN275201000009C, and HHSN275201000001Z.

Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted OR

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- GDM

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- LMP

Last Menstrual Period

- NICHD

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- sTfR

Soluble Transferrin Receptor

Footnotes

Duality of interest: The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement: SR conducted the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SNH contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript. WB contributed to study coordination, data interpretation, and manuscript reviewing. YZ contributed to data management, data analysis and interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. JG contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. PSA contributed to data analysis and interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. NLW and MYT assisted with laboratory testing and reviewed the manuscript. CZ obtained funding, designed and oversaw the study and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical interpretation of the results, reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version of the manuscript, and have agreed to be accountable for his/her role in this manuscript. SR and CZ are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Scholl TO, Reilly T. Anemia, iron and pregnancy outcome. J Nutr. 2000;130:443S–447S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.443S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonagh M, Cantor A, Bougatsos C, Dana T, Blazina I. Routine Iron Supplementation and Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. [accessed 6 September 2016]. (Evidence Syntheses, No. 123.) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen JB, Moen IW, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Iron: the hard player in diabetes pathophysiology. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;210:717–732. doi: 10.1111/apha.12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montonen J, Boeing H, Steffen A, et al. Body iron stores and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2613–2621. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Z, Li S, Liu G, et al. Body iron stores and heme-iron intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zein S, Rachidi S, Hininger-Favier I. Is oxidative stress induced by iron status associated with gestational diabetes mellitus? J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014;28:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL, Kirwan JP, Catalano PM, Friedman JE. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S112–119. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zein S, Rachidi S, Awada S, et al. High iron level in early pregnancy increased glucose intolerance. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2015;30:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khambalia AZ, Collins CE, Roberts CL, et al. Iron deficiency in early pregnancy using serum ferritin and soluble transferrin receptor concentrations are associated with pregnancy and birth outcomes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:358–363. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarim E, Kilicdag E, Bagis T, Ergin T. High maternal hemoglobin and ferritin values as risk factors for gestational diabetes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84:259–261. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Scholl TO, Stein TP. Association of elevated serum ferritin levels and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women: The Camden study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1077–1082. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowers KA, Olsen SF, Bao W, Halldorsson TI, Strom M, Zhang C. Plasma Concentrations of Ferritin in Early Pregnancy Are Associated with Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. J Nutr. 2016;146:1756–1761. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.227793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harms K, Kaiser T. Beyond soluble transferrin receptor: old challenges and new horizons. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skikne BS, Flowers CH, Cook JD. Serum transferrin receptor: a quantitative measure of tissue iron deficiency. Blood. 1990;75:1870–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skikne BS. Circulating transferrin receptor assay--coming of age. Clin Chem. 1998;44:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1434–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young MF, Griffin I, Pressman E, et al. Maternal hepcidin is associated with placental transfer of iron derived from dietary heme and nonheme sources. J Nutr. 2012;142:33–39. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.145961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derbent AU, Simavli SA, Kaygusuz I, et al. Serum hepcidin is associated with parameters of glucose metabolism in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1112–1115. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.770462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buck Louis GM, Grewal J, Albert PS, et al. Racial/ethnic standards for fetal growth: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:449 e441–449 e441. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:525–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lao TT, Chan PL, Tam KF. Gestational diabetes mellitus in the last trimester - a feature of maternal iron excess? Diabet Med. 2001;18:218–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amiri FN, Basirat Z, Omidvar S, Sharbatdaran M, Tilaki KH, Pouramir M. Comparison of the serum iron, ferritin levels and total iron-binding capacity between pregnant women with and without gestational diabetes. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:302–305. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.116977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afkhami-Ardekani M, Rashidi M. Iron status in women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2009;23:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soubasi V, Petridou S, Sarafidis K, et al. Association of increased maternal ferritin levels with gestational diabetes and intra-uterine growth retardation. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharifi F, Ziaee A, Feizi A, Mousavinasab N, Anjomshoaa A, Mokhtari P. Serum ferritin concentration in gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of subsequent development of early postpartum diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:413–419. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S15049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javadian P, Alimohamadi S, Gharedaghi MH, Hantoushzadeh S. Gestational diabetes mellitus and iron supplement; effects on pregnancy outcome. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:385–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gungor ES, Danisman N, Mollamahmutoglu L. Maternal serum ferritin and hemoglobin values in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maitland RA, Seed PT, Briley AL, et al. Prediction of gestational diabetes in obese pregnant women from the UK Pregnancies Better Eating and Activity (UPBEAT) pilot trial. Diabet Med. 2014;31:963–970. doi: 10.1111/dme.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khambalia AZ, Aimone A, Nagubandi P, et al. High maternal iron status, dietary iron intake and iron supplement use in pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective study and systematic review. Diabet Med. 2015;33:1211–21. doi: 10.1111/dme.13056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenig MD, Tussing-Humphreys L, Day J, Cadwell B, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis during pregnancy. Nutrients. 2014;6:3062–3083. doi: 10.3390/nu6083062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh T, O’Broin SD, Cooley S, et al. Laboratory assessment of iron status in pregnancy. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1225–1230. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Santen S, Kroot JJ, Zijderveld G, Wiegerinck ET, Spaanderman ME, Swinkels DW. The iron regulatory hormone hepcidin is decreased in pregnancy: a prospective longitudinal study. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:1395–1401. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajpathak SN, Crandall JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Kabat GC, Rohan TE, Hu FB. The role of iron in type 2 diabetes in humans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez-Real JM, McClain D, Manco M. Mechanisms Linking Glucose Homeostasis and Iron Metabolism Toward the Onset and Progression of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2169–2176. doi: 10.2337/dc14-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Facchini FS, Saylor KL. Effect of iron depletion on cardiovascular risk factors: studies in carbohydrate-intolerant patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Real JM, Penarroja G, Castro A, Garcia-Bragado F, Hernandez-Aguado I, Ricart W. Blood letting in high-ferritin type 2 diabetes: effects on insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2002;51:1000–1004. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]