Abstract

The synaptic protein SHANK3 encodes a multidomain scaffold protein expressed at the postsynaptic density of neuronal excitatory synapses. We previously identified de novo SHANK3 mutations in patients with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and showed that SHANK3 represents one of the major genes for ASD. Here, we analyzed the pyramidal cortical neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells from four patients with ASD carrying SHANK3 de novo truncating mutations. At 40–45 days after the differentiation of neural stem cells, dendritic spines from pyramidal neurons presented variable morphologies: filopodia, thin, stubby and muschroom, as measured in 3D using GFP labeling and immunofluorescence. As compared to three controls, we observed a significant decrease in SHANK3 mRNA levels (less than 50% of controls) in correlation with a significant reduction in dendritic spine densities and whole spine and spine head volumes. These results, obtained through the analysis of de novo SHANK3 mutations in the patients’ genomic background, provide further support for the presence of synaptic abnormalities in a subset of patients with ASD.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are characterized by atypical social communications, and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. ASD frequently co-occur with additional comorbidities such as intellectual disability (ID) and epilepsy1. The genetic architecture of ASD differs among individuals, ranging from apparently monogenic to polygenic forms2. Among the genes recurrently found mutated in individuals with ASD, the SHANK genes code for synaptic scaffolding proteins located at glutamatergic synapses. SHANK mutations can occur in patients with ASD with an intelligence quotient in the normal range (SHANK1), but mostly in patients with mild (SHANK2) to severe (SHANK3) ID3. SHANK3 haploinsufficiency also contributes to the clinical symptoms of patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) characterized by a terminal deletion of chromosome 22q13 that includes SHANK3 in the large majority of cases4. SHANK3 mutations represent a relatively frequent genetic cause for ASD accounting for 1–2% of individuals with ASD and ID3,5. In addition, truncating SHANK3 mutations were also reported in rare cases of schizophrenia6.

SHANK proteins are located at postsynaptic densities (PSD) of excitatory neurons in different brain areas7. They are cytoskeletal scaffold proteins involved in the formation/function of dendrites. SHANK3 recruits a large number of synaptic intracellular interactors such as Homer as well as several neurotransmitter receptors including the α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA), the metabotropic glutamate (mGlu), and the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) glutamate receptors8. On average, each single glutamatergic synapse contains approximately 300 SHANK family proteins (SHANK1-3), which correspond to approximately 5% of the total number of synaptic proteins9. A defect in the expression of one SHANK member causes significant synaptic deficiencies as evaluated by using animal models and cultured neurons. In mice, disruption of the Shank3 gene alters excitatory synaptic transmission and leads to autistic-like behaviors such as social communication deficits and repetitive behaviors10–14. By contrast, overexpression of Shank3 in cultured aspiny cerebellar neurons triggers the development and maturation of functional spines expressing NMDA, AMPA and metabotropic glutamatergic receptors15. This overexpression approach in rat neurons in culture was also used to characterize the functional impact of SHANK mutations on the reduction of dendritic spines density16,17. In a recent study, Mei et al.18 generated a conditional knock-in mouse model in which the re-expression of the Shank3 gene restores spine densities in the adult striatum. In this model, the social communication deficits and the repetitive grooming behaviors were also specifically restored. By contrast, motor coordination and anxiety remain unchanged. All together, both in vitro and in vivo data indicate a significant role of SHANK3 protein in the regulation of synaptic plasticity with possible reversion of the observed deficits at the adult stage.

In humans, six studies investigated the role of SHANK3 using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). Results from four studies in which iPSC-derived neurons from patients were used showed a reduction in dendritic spine or excitatory synaptic transmission as compared with controls19–22. These effects can be reversed by SHANK3 overexpression, insulin growth factor 1 (IGF1) treatment19, Cdc2-like kinase 2 (CLK2) inhibition20 or lithium treatment21. Another study using iPSC-derived enterocytes revealed a decrease in zinc uptake transporter that could play a role in the gastro-intestinal symptoms of the patients23. It should be noted that most of these studies used cells from patients with PMS who were carriers of relatively large 22q13.3 deletions, encompassing not only SHANK3 but also additionnal genes that could also contribute to the phenotype4. One study used genome-editing technologies to introduce SHANK3 single nucleotide mutations in iPSC-derived neurons from controls24. The authors showed that heterozygous and homozygous SHANK3 truncating mutations severely impair hyperpolarization-active cation channels (HCN) that are associated with reduced synaptic connectivity and transmission24. All these results converge towards a synaptic deficit in patients with ASD carrying a SHANK3 mutation, but none of the previous studies has investigated the dendrite morphology of neurons carrying SHANK3 truncating mutations in the patient genetic background. In the present study, we selected four independent patients carrying heterozygous truncating de novo SHANK3 point mutations who had initially been characterized in our laboratory3. We generated the corresponding iPSCs for their selective reprogramming into cortical neurons in order to examine the effects of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency on the level of SHANK3 mRNA and on the 3D spine morphogenesis organization.

Results

Characterization of iPSC-derived neurons from patients with SHANK3 de novo mutations

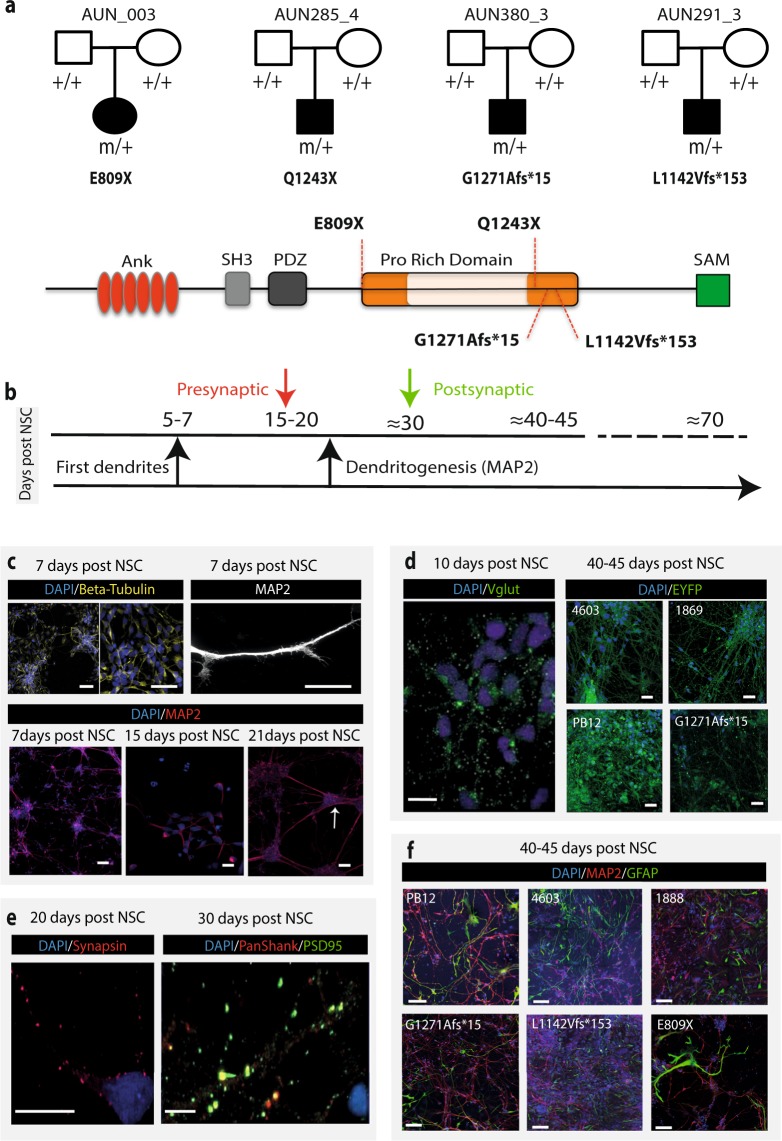

We used the human iPSC-based model to analyze the effects of heterozygous truncating de novo SHANK3 mutations found in four patients with ASD, and presenting moderate to severe ID. Their clinical symptoms are fully described in Leblond et al.3. The schematic location of the selected mutations in SHANK3 protein is shown in Fig. 1a. The four mutations are predicted to lead to truncated proteins either by inducing a stop codon directly (E809X and Q1243X) or via a frameshift of the open reading frame (G1271Afs*15 and L1142Vfs*153). For clarity, the six ankyrin domains are presented in their 3D structure to illustrate precisely their number and complete juxtaposition (Supplementary Fig. 1). Indeed, some contradictory results have been published regarding the topological characteristics of the ANK domains25,26. Other SHANK3 domains such as SH3, PDZ and SAM are also complex structures that are involved in the interaction of SHANK3 proteins with its intracellular partners26. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the main technical steps for fibroblasts reprogramming into pluripotent stem cells, commitment to the dorsal telencephalon lineage, derivation, amplification and banking of late cortical progenitors (LCP) as previously described27. LCP were differentiated into cortical neurons of the superficial layers II-IV, which correspond to the cortical upper layers as confirmed previously by Cux1, Cux2 and Brn2 immunolabeling27. We used fibroblasts from patients with E809X and Q1243X mutations27 and fibroblasts from one patient with G1271Afs*15 mutation21. The characterization of iPSC derived from the fibroblast of patient L1142Vfs*153 was not reported previously and is presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. In addition, we derived similar cortical glutamatergic neurons from three independent control individuals, namely 1869, 4603 and PB1221,27. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the different steps of culture that allow the production of a significant percentage of mature neurons and study workflow. Figure 1b shows the different maturation steps of the neurons obtained at 40–45 days post neural stem cells (NSC) differentiation. We first checked for the absence of any significant variability in the growth of neurites between single culture samples using the MAP2 staining28,29 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 4). According to our protocol, iPSC were predominantly derived into glutamatergic neurons as illustrated by VGlut1 immunoflorescence staining and the selective expression of the yellow fluorescent protein drived by the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) promoter (Fig. 1d). This promoter is predicted selective for pyramidal excitatory neurons vs. inhibitory interneurons30. In accordance with Boissart et al.28, these neurons accounted for 70–80% of total cells whereas GABAergic neurons accounted for about 15% (data not shown). Our data clearly indicate a predominant presence of glutamatergic cells in the culture, independently of the cellular phenotypes (CTR vs. ASD). Finally, we determined the appearence of presynaptic and postsynaptic components by synapsin and PSD95 immunofluorescence staining. Colocalisation of SHANK and the excitatory marker PSD95 was first detectable at 30 days after NSC differentiation (Fig. 1e). We observed that neuronal cells could be kept in culture for about 70 days after NSC differentiation. However, they were not always at a full cellular viability. The time slot of 40–45 days therefore appeared convenient to study dendritic spine maturation and morphometry while preventing any cellular death. At this stage of maturation, we could also detect the presence of astrocytes accounting about 5–10% of total cells in control and ASD neuronal cultures (Fig. 1f). Astrocytes are known for their role in promoting the maturation of NSC31. They influence the local environment of iPSC-derived neurons, their maturation and promote synaptogenesis32.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of the families carrying de novo SHANK3 mutations and neuronal characterization. (a) Upper, the four patients probands carry de novo truncating mutations in SHANK3 gene (two « STOP » and two « frameshift » mutations leading to a premature STOP codon). (a) Lower, A schematic representation of the multidomain SHANK3 protein with the location of the four mutated aminoacids is provided. Conserved domains are indicated by filled rectangles. The mutations are located within the Proline-rich structure of SHANK3, between the PDZ and the SAM domains, and within exon 21 of SHANK3 gene. (b) Schematic representation of neuron maturation at different time periods. (c) Upper left, Immunofluorescence staining of human control iPSC cells-derived neurons by beta III tubulin at 7 days post NSC differentiation. (c) Upper right, labeling of a single dendrite using the MAP2 marker showing dendritic growth cones at early stages of culture. (c) Lower, Immunofluorescence staining of human iPSC cells-derived neurons by MAP2 at different intervals of time post NSC differentiation. The target shows neurite elongation and established connectivity between cell clusters. (d) VGlut1 marker at 10 days post NSC differentiation stained glutamatergic neurons. Labeling of control (1869, 4603, PB12) and ASD (G1271Afs*15) mature neurons at 40–45 days post NSC differentiation using the pAAV-CaMKIIa-hChR2-EYFP-WPRE lentivirus are also illustrated. (e) Immunofluorescence staining using presynaptic (synapsin) and postsynaptic (PSP95 and PanSHANK) markers. No staining was detectable before the indicated days post NSC differentiation (20 days for Synapsin, 10 days for VGlut1 and 30 days for PSD95). Data are from at least two control individuals (PB12 and 4603) (f) Immunofluorescence GFAP staining of cultures from iPSC-derived neurons showing the presence of astrocytes in 3 controls individuals (PB12, 4603, 1888) and 3 patients (G1271Afs*15, L1142Vfs*153, E809X). Scale bars: 10 μm (a-e); 100 μm (f).

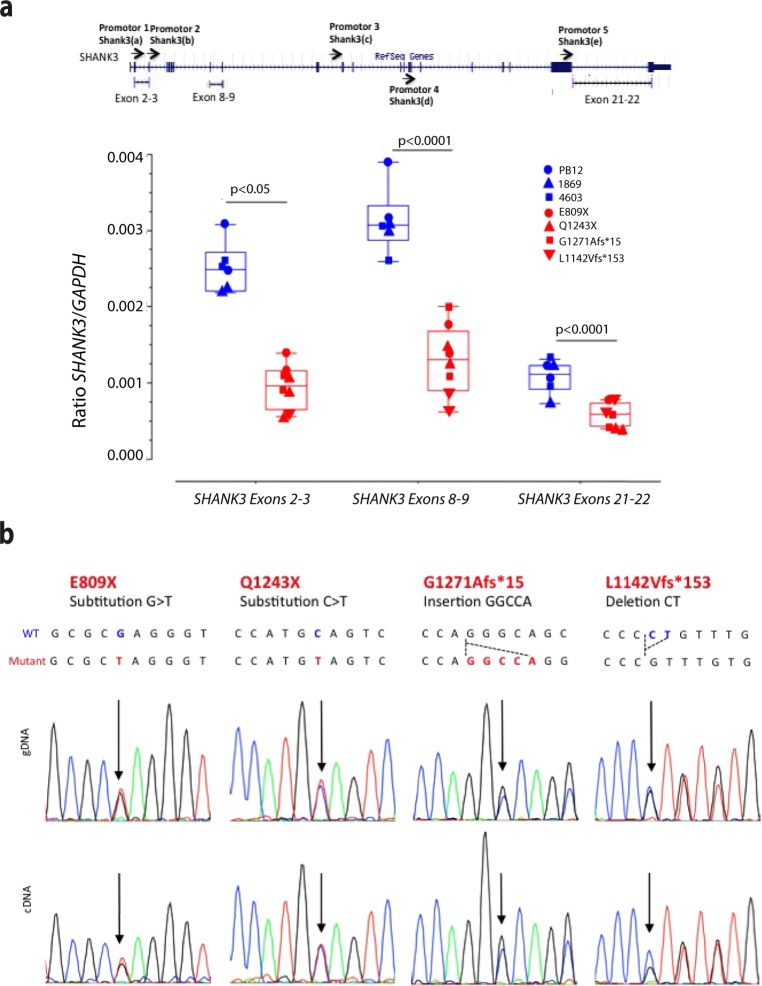

SHANK3 expression in iPSC-derived neurons from patients and control individuals

We investigated SHANK3 expression in iPSC-derived neurons from control individuals and patients. SHANK3 mRNA were quantified using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)33 after reverse transcription (RT) of mRNA from cells in culture. SHANK3 mRNA levels were significantly decreased by an average of 25% to 50% in patients as compared with controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). RNAseq experiments show similar decrease in SHANK3 mRNA levels as well as an enrichment of under-expressed genes among the genes targeted by Fragile-X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (Supplementary Fig. 5). By contrast, housekeeping genes were not enriched in genes which were differently expressed in neurons from ASD patients as compared with control neurons (Supplementary Fig. 5). We then sequenced the genomic and cDNA to detect the level of SHANK3 mutated allele (primers are presented in Supplementary Table S1). Surprisingly, the mutant allele was present with a similar ratio between mutant and wild-type alleles in all patients’ cDNA (Fig. 2). These data also indicate that under our experimental conditions, the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) mechanism devoted to the elimination of mRNA transcripts with premature stop codons appears inefficient. This might reflect previous observations of NMD dysfunction during neuronal cell development34. Studies would be necessary to confirm the decrease in the levels of SHANK3 proteins in samples from patients.

Figure 2.

Analysis of SHANK3 gene expression in iPSC-derived neurons from controls and ASD patients. (a) Quantification of SHANK3 mRNA in iPSC-derived neurons (40 days post NSC) using RT-ddPCR. Data are mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way Anova. *p < 0.05 ***p < 0.001 (b) Sequencing diagrams showing the presence of the four mutations in the genomic and cDNA extracted from iPSC-derived neurons.

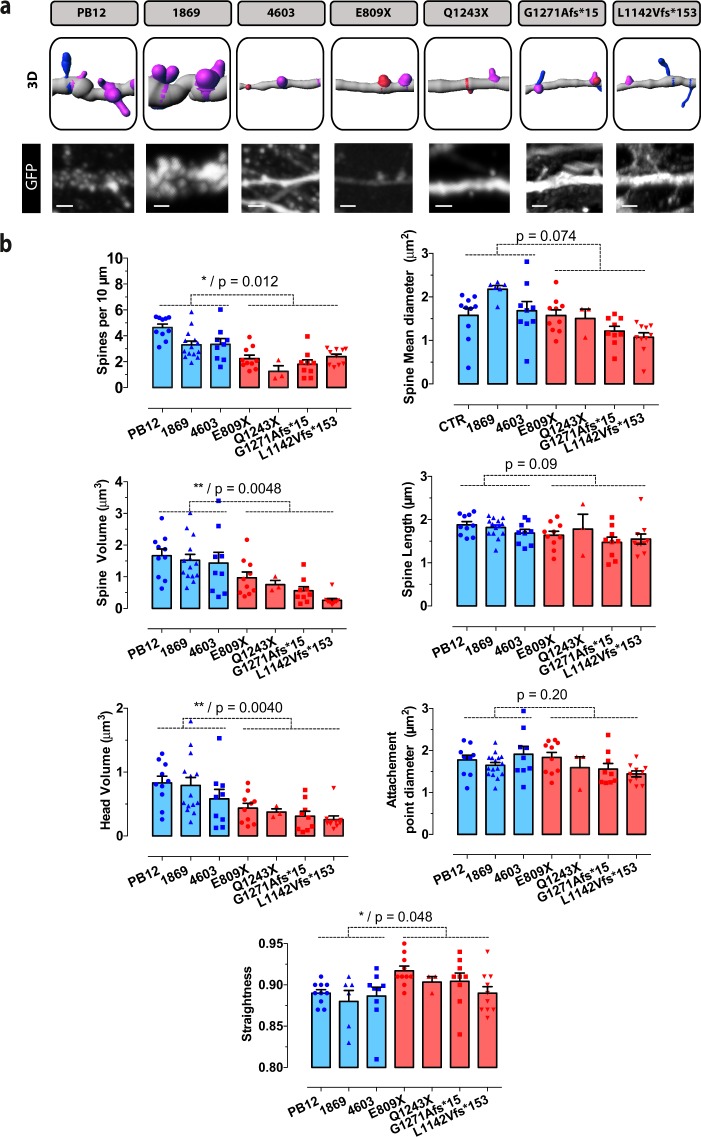

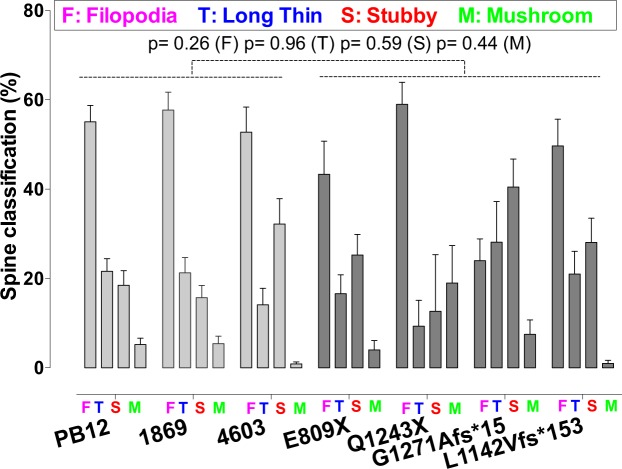

Spinogenesis in pyramidal neurons derived from iPSC is correlated to SHANK3 expression

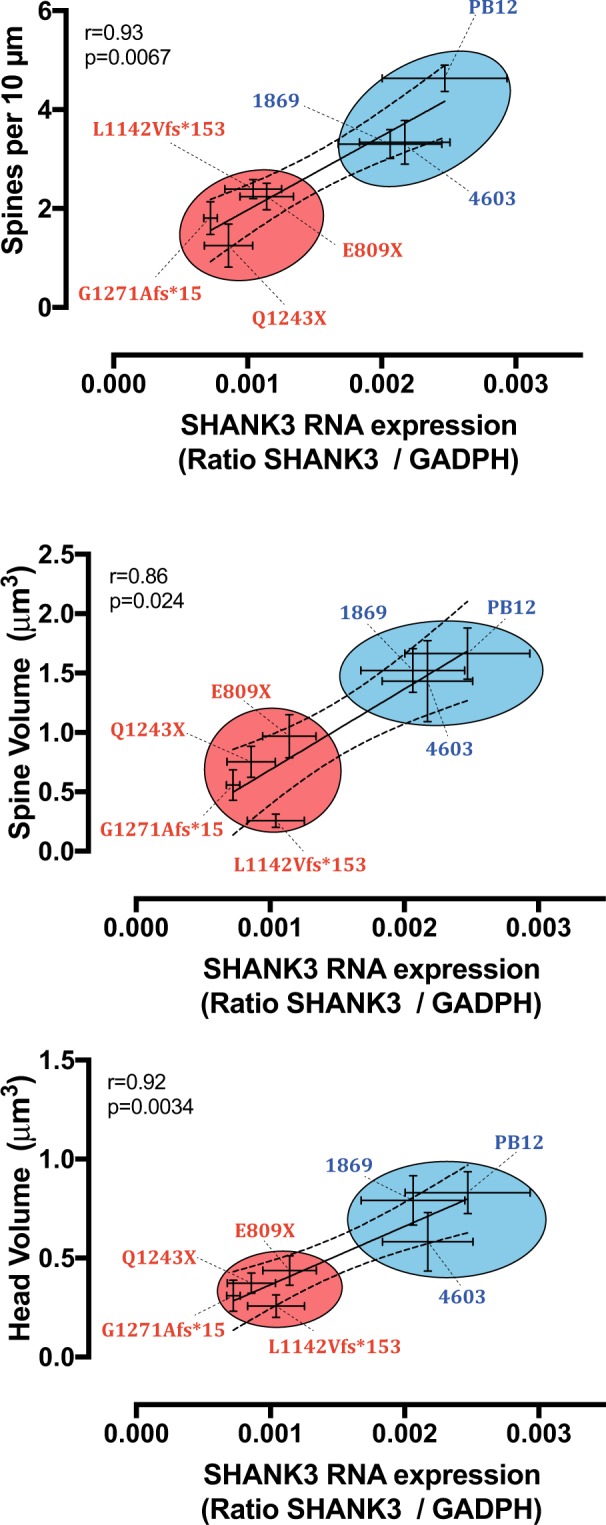

Reduced SHANK3 levels are expected to modify dendritic spine morphology. We therefore measured spinogenesis in iPSC-derived pyramidal glutamatergic cells by comparing the primary dendrites of neurons from patients with ASD to those from three control individuals (Fig. 3a,b). Our data show a significant decrease of nearly 50% in spine densities in all the four patients as compared to the three control individuals. The total volume of spines, as well as their head volume was also decreased to a similar extent. Spine straightness was slightly increased in patients but this change was less pronounced than those observed on spine densities and volumes. Spine mean diameter and spine length as well as the surface of spine attachment to the dendrite remained globally constant between patients and control individuals (Fig. 3b). Our data indicate that all spine categories were represented in pyramidal neurons from both patients and controls. However, we observed some differences in their relative proportions: filopodia were present at highest densities in both control individuals and patients as compared to the combined thin, stubby and muschroom categories (p < 0.0001). By contrast, we did not observe any significant difference in spine maturation between patients and controls (Fig. 4). When SHANK3 mRNA levels and dendrites were analyzed together, we found a significant correlation between the level of SHANK3 mRNA and spine density (p = 0.0067), spine volume (p = 0.024) and spine head volume (p = 0.0034) (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of the morphological parameters of primary dendritic spines between control and ASD neurons. (a) Primary spine segments with corresponding 3D reconstructions. Scale bar = 2 μm. Dendrite segments (grey color) are endowed with four categories of spines: Filopodia (pink color), Thin (blue), Stubby (pink) and Muschroom (green). (b) Spine morphological parameters were quantified using the Imaris sofware as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers of neuronal dendrites are indicated in the graph. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student t-test in order to analyze the significance between mean values from combined controls and combined patients. Equality of variances was checked using the Fisher’s F-test. P values are directly indicated in the graph. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Morphological classification of primary dendritic spines between control and ASD neurons. Morphological parameters of the four spine categories were quantified using the Imaris sofware as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student t-test. Equality of variances was checked using the Fisher’s F-test. P values are directly indicated in the graph. Combined mean values for Filopodia were significantly increased as compared to combined values from all other spine categories (p < 0.0001). Statistical analysis was performed as described above.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis between SHANK3 expression and alterations in dendritic spine parameters in iPSC-derived neurons from control individuals and patients with ASD. Upper graph, Correlation between SHANK3 mRNA and spine densities. Middle graph, Correlation between SHANK3 mRNA and total spine volume. Lower graph, Correlation between SHANK3 mRNA and head spine volume. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 6 software (GraphPad, sand Diego, California, USA). Data are mean ± SEM. Coefficients were calculated using Spearman correlation method and are indicated in the graphs with statistical significance.

Discussion

In brain cortical circuits, dendritic spines play an important role in the establishement of excitatory synapses. However, their quantitative morphological analysis has been poorly documented in iPSC-derived neurons from patients with ASD. We therefore analyzed spinogenesis in iPSC-derived pyramidal glutamatergic cells using our published method for the 3D quantification of GFP-labeled dendritic spines35. So far, data from studies using iPSC-derived neurons in neurodevelopmental disorders have included only one or two patients. In our study, we have increased the number to four ASD patients with precise SHANK3 mutations. This aspect is of importance since each individual has a unique genetic background. In addition, a broad range of severe clinical symptoms are observed in patients carrying SHANK3 mutations3,4,36. Finally, recent observations indicate a dysregulation of different microbial species in Shank3 KO mice37 that may affect GABAergic system38 together with an apparent complex relationship between SHANK3 genotype, sex and immune response37. These observations strengthen the importance of using a larger number of patients for the analysis of cellular phenotypes in humans.

We could observe altered 3D spine morphologies and densities in comparison with control neurons in iPSC-derived neurons from four patients with ASD carrying SHANK3 de novo truncating mutations. Moreover, we could also correlate the reduced expression of SHANK3 mRNA in neurons reprogrammed from patients’fibroblasts with the effects of the four distinct SHANK3 mutations on spinogenesis. In neuronal cells, a dendritic mRNA transport occurs with local translation at dendritic spines39. The decrease in SHANK3 mRNA levels may result from reduced spine densities as observed in reprogrammed neurons from patients. The spatio-temporal control of gene expression which occurs at synapses involves the FMRP protein. FMRP target genes which are also subject to dendritic mRNA transport with local translation at synaptic sites40 were enriched in down-regulated genes.

Our data are in agreement with the findings of Shcheglovitov et al.19 showing fewer excitatory synapses in iPSC-derived neurons obtained from two patients with PMS carrying a complete deletion of SHANK3 as compared to controls. Our data are also in agreement with those reported in rat neurons by Durand et al.16 who demonstrated by a 2D spine analysis, that a stop SHANK3 mutation selectively reduced the density of spines along the dendrites, while spine width remained unchanged. In the study of Bidinosti et al.20 using rat cortical neurons, spine densities were in the same of order as those from our study. Moreover, these authors found that inactivating SHANK3 led to a similar reduction in spine densities. Altered dynamics of maturation of spines from excitatory neurons during development may underlie the cortical dysfunctions found in ASD by modifying the intracortical projections of excitatory neurons. We could observe that spine maturation is not fully achieved. Filopodia were present at the highest densities in controls and in patients, as compared to other spine categories. The distribution of spine categories in patient G1271Afs*15 was slightly different with apparent lower levels of filopodia as compared with other individuals. Dendritic spine dysgenis in neurons from ASD patients may underlie the synaptic defects found in diverse mouse models of ASD41,42. An inadequate organization of neuronal circuits may cause the main clinical behavioral deficits, also reproducible in mouse models. At molecular levels, the genetic manipulation of selected proteins such as Shank3 but also Shank2, as well as neurexins, neuroligins, Epac2, Tsc1/2, Ube3A, and PTEN that are involved in ASD, leads to altered spine shapes and densities in rodent models43. Current advances in SHANK3 protein research clearly correlate its deficit to a wide-range of human neurological disorders with developmental synaptic dysfunction that may also be associated with synaptic decline at later stages as observed in Alzheimer disease44. The fact that Shank3 protein has been shown to differentially regulate brain cortical and striatal circuits in mice45, further supports its complex involvement not only in ASD but also in other neurological disorders.

In conclusion, our results obtained on iPSC-derived neurons from four independent patients with ASD and ID fully support the deleterious role of SHANK3 mutations on dendrite density and morphology in the patient genetic background. This abnormality of dendrites is a current feature, which is also observed in iPSC-derived neurons from patients with neurodevelopmental syndromes (i.e. PMS, Rett syndrome, Timothy syndrome, Fragile X syndrome) as reviewed elsewhere46–49. The 3D measurement of the dendritic spines morphologies represents a useful index for synaptic defects in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Methods

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We confirm that all experimental protocols were approved by the named institutions. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects as detailed below.

Ancestry analysis of patients

For the ancestry analysis, patients and control individuals were genotyped using Illumina Infinium Omni1/2.5 (1 M/2.5 M SNPs) and Illumina Infinium Humancore24 (300 K SNPs) beadchips, respectively. To assess the genetic background of patients and controls, genotyping data from HapMap3 populations was used as a reference panel and the genetic distance based on pairwise identity by state calculation was performed using PLINK and 17 K SNPs (overlapping SNPs from the Illumina technologies) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Production of human pluripotent Stem cells and their derivation into cortical neurons of layer II to IV

The iPSC were produced as described previously27. Following the patient’s legal representatives’ approval, 8-mm skin punch biopsies were obtained (study approval by Committee for the Protection of Persons, CPP no. C07-33). The clinical characteristics have been published3. Fibroblasts reprogramming was performed using the four genes coding for the human factors OCT4, SOX2, c-Myc, and KLF4 cloned in Sendai viruses (Invitrogen). Induced PSC lines were characterized according to Boissart et al.27. Commitment of pluripotent stem cells (PSC) to the neural lineage and derivation of stable cortical neural stem cells (NSC) was also described previously27,35. For the control iPSC lines, we used GM04603 and GM01869, two male fibroblast cultures obtained from the Coriell Biorepository (Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, NJ, USA). The control line PB12 was reprogramed from peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from an anonymous female blood donor at the French Blood Donor Organization.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was described in Gouder et al.32. The list of primary and secondary antibodies with their respective dilutions is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Lentiviral transduction

The protocol for the transduction of PGK-GFP-lentivirus has been previously described32. The same experimental conditions were used for the pAAV-CaMKIIa-hChR2-EYFP-WPRE lentivirus without subsequent immunofluorescence against the yellow fluorescent protein. The CaMKIIa promoter is predicted to drive specific expression in neurons vs. glia and in pyramidal excitatory neurons vs. inhibitory interneurons28. Transduction of neuronal cultures was performed using a lentivirus containing a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) promoter provided by Dr Gabriel Lepousez.

Primary dendritic spine imaging

For imaging of dendritic spines, a step-by-step protocol has been previously published and is available in a video journal32. Main steps are as follows: (1) transduction of iPSC-derived cells with GFP lentiviral vectors followed by an immunofluorescence labeling with an anti-GFP antibody; (2) confocal imaging by a confocal laser-scanning microscope using a 40X oil NA = 1.3 objective and a 488 nm laser for GFP excitation; (3) selection of neurons with a pyramidal morphology; (4) Z-stack acquisitions with a Z spacing ranging from 150 nm to 300 nm; (5) Semi-automatic tracing of dendrites and automated segmentation of spines using the Filament Tracer module of Imaris 7.6 software (Bitplane AG, Zürich); (6) Spine classification in four classes defined by their morphology as follows: Stubby: length < 1μm; Muschroom: Length (spine) > 3 μm and Max width (head) > mean width (neck) x 2; Long thin: Mean width (head) ≥ Mean width (neck); Filopodia-like: length > 1 μm (no head).

Genomic, cDNA sequencing, and Genotyping

For genomic DNA sequencing, cells were lyzed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH = 8.0, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) with proteinase K. DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform isoamylalcool (ref. P2069, Sigma) and isopropanol (ref. 59309-1L, Sigma). For cDNA sequencing, RNA was extracted using the miRNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript ® VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (ref. 11754–250, Invitrogen). The region encompassing the mutation was amplified by PCR using 5 or 4 sets of primers for the genomic DNA and cDNA, respectively (Supplementary Table S1) and the Kapa2G polymerase (KAPA 2G Robust HotStart PCR Kits, ref. KK5517, Clinisciences). PCR products were run on agarose gels and purified using phosphatase (FastAP, ref. EF0651, ThermoScientific) and exonuclease enzymes (Exonuclease I, EN0581, ThermoScientific). Controls were performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Sequencing was performed using the BigDye®TerminatorV3.1 cycle sequencing and purifications kits (ref. 4337455,4376484, ThermoFisher).

RT-ddPCR assay

RNAs from 40-day human neurons in culture were extracted using the miRNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, ref. 217004) and converted in cDNA using the Superscript ® VILO cDNA synthesis Kit (ref. 11753–250, Invitrogen). The expression of SHANK3 mRNA was analyzed using 3 sets of primers and probes targeting respectively exons 2-3, 8-9 and 21-22. A duplex ddPCR strategy was used to amplify and quantify SHANK3 and the housekeeping gene GADPH in a same well. For each set of primers targeting SHANK3, probes were coupled either with the FAM dye or with the HEX dye. Each reaction medium contained 10 μl ddPCR Supermix for probes (without UTP), 1 μl of SHANK3 primer/probe mix (Biorad), 1 μl of GADPH assay (Biorad), 6 μl of nuclease free water, and 2 μl of DNA (2.5 ng/μl). 20 μl of each reaction medium was transferred to a droplet generation cartridge before adding 70 μl of Droplet Generation Oil. Droplets generated with QX200 Droplet Generator were loaded into a clean 96-well PCR plate, sealed with foil. The PCR reaction conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 1 cycle at 55 °C for 1 min, followed by 1 cycle at 98 °C for 10 min. Droplet signals were obtained using a Bio-Rad QX200 droplet digital PCR system (Bio-Rad, USA). Data were analyzed using the Bio-Rad QuantaSoft software version 1.3.2. Negative controls were obtained by excluding the retrotranscription step. Up to 20000 discrete droplets were analyzed for each PCR sample (Supplementary Table S3).

Statistics

The sample size and statistical analyses are reported in each figure legend. 95% confidence levels have been used.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Clinical Investigation Center of Robert Debré hospital for assistance with patient recruitment, sampling and fibroblast preparations. The French Ministry of Education provided the fundings for LG and AV’s PhDs. Other fundings for this study were provided by grants from the French National Research Agency ANR (ANR-13-SAMA-0006; SynDivAutism), the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation, the Cognacq Jay Foundation, and the Fondamental Foundation. I-Stem is part of the Biotherapies Institute for Rare Diseases (BIRD) supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM-Téléthon). We are grateful to Pascal Roux for sharing his expertise in spectral confocal microscopy. This study used samples from the NINDS Human Genetics Resource Center DNA and Cell Line Repository, as well as clinical data. NINDS Repository sample numbers corresponding to the samples used are GM01869 (“1869”), GM04603 (“4603”) and GM01888 (“1888”). PB12 was reprogrammed from blood samples provided by the French National Blood Collection Center (Etablissement Français du Sang, EFS).

Author Contributions

I.C.T. and T.B. conceived the study. I.C.T. was in charge of the overall direction and planning. L.G., A.V., H.G.B. carried out the neurobiological experiments in collaboration with J.Y.T., A.D., G.A.L. and E.A. N.L. and C.S.L. contributed to the genetic analyses. R.D. was responsible for the recruitment and clinical evaluation of subjects. A.B. and A.P. performed the reprogrammation of fibroblasts. A.Bi., A.Bo. and J.F.D. contributed to the RNAseq experiments.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Laura Gouder, Aline Vitrac and Hany Goubran-Botros contributed equally.

Thomas Bourgeron and Isabelle Cloëz-Tayarani jointly supervised this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-36993-x.

References

- 1.Gillberg C. The ESSENCE in child psychiatry: early symptomatic syndromes eliciting neurodevelopmental clinical examinations. Rev. Disabil. 2010;31:1543–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourgeron T. From the genetic architecture to synaptic plasticity in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:551–563. doi: 10.1038/nrn3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leblond CS, et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabet A-C, et al. A framework to identify contributing genes in patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. NPJ Genomic Medecine. 2017;2:32. doi: 10.1038/s41525-017-0035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durand CM, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:25–27. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauthier J, et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7863–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906232107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang YH, Ehlers MD. Modeling Autism by SHANK Mutations in Mice. Neuron. 2013;78:8–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomasetti C, et al. Treating the synapse in major psychiatric disorders: the role of postsynaptic density network in Dopamine-Glutamate interplay and psychopharmacologic drugs molecular actions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:E135. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugiyama Y, Kawabata I, Sobue K, Okabe S. Determination of absolute protein numbers in single synapses by a GFP-based calibration technique. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:677–684. doi: 10.1038/nmeth783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bozdagi O, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the autism-associated Shank3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication. Mol Autism. 2010;1:1–15. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peça J, et al. Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature. 2011;472:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nature09965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, et al. Synaptic dysfunction and abnormal behaviors in mice lacking major isoforms of Shank3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:3093–3108. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang M, et al. Reduced excitatory neurotransmission and mild autism-relevant phenotypes in adolescent Shank3 null mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6525–6541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6107-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, et al. Mice with Shank3 Mutations Associated with ASD and Schizophrenia Display Both Shared and Distinct Defects. Neuron. 2016;89:147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roussignol G, et al. Shank expression is sufficient to induce functional dendritic spine synapses in aspiny neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3560–3570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4354-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durand CM, et al. SHANK3 mutations identified in autism lead to modification of dendritic spine morphology via an actin-dependent mechanism. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:71–84. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochoy DM, et al. Phenotypic and functional analysis of SHANK3 stop mutations identified in individuals with ASD and/or ID. Mol. Autism. 2015;6:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei Y, et al. Adult restoration of Shank3 expression rescues selective autistic-like phenotypes. Nature. 2016;530:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature16971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shcheglovitov A, et al. SHANK3 and IGF1 restore synaptic deficits in neurons from 22q13 deletion syndrome patients. Nature. 2013;503:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature12618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binidosti M, et al. CLK2 inhibition ameliorates autistic features associated with SHANK3 deficiency. Science. 2016;351:1199–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darville H, et al. Human pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical neurons for high throughput medication screening in autism: a proof of concept study in SHANK3 haploinsufficiency syndrome. EBiomedecine. 2016;9:293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathuria A, et al. Stem cell-derived neurons from autistic individuals with SHANK3 mutation show morphogenetic abnormalities during early development. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;00:1–12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaender S, et al. Zinc deficiency and low enterocyte zinc transporter expression in human patients with autism related mutations in SHANK3. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45490. doi: 10.1038/srep45190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yi F, et al. Autism-Associated SHANK3 haploinsufficiency Causes Ih-Channelopathy in Human Neurons. Science. 2016;352:aaf2669. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuetz G, et al. The neuronal scaffold protein Shank3 mediates signaling and biological function of the receptor tyrosine kinase Ret in epithelial cells. J. Cell. Biol. 2004;167:945–952. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mameza MG, et al. SHANK3 gene mutations associated with autism facilitate ligand binding to the Shank3 ankyrin repeat region. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26697–26708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boissart C, et al. Differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells of cortical neurons of the superficial layers amenable to psychiatric disease modeling and high-throughput drug screening. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e294. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercati O, et al. Contactin 4, -5 and -6 differentially regulate neuritogenesis while they display identical PTPRG binding sites. Biol Open. 2011;2:324–334. doi: 10.1242/bio.20133343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercati O, et al. 2017. CNTN6 mutations are risk factors for abnormal auditory sensory perception in autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:625–633. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osten, P., Dittgen, T. & Licznerski, P. Lentivirus-based genetic manipulations in neurons in vivo. In: Kittler, J. T. & Moss, S. J., editors. The Dynamic Synapse: Molecular Methods in ionotropic receptor biology. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. Frontiers in Neuroscience Chapter 13 (2006).

- 31.Song H, Stevens CF, Gage FH. Astroglia induce neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells. Nature. 2002;417:39–44. doi: 10.1038/417039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slezak M, Pfrieger FW. New roles for astrocytes: regulation of CNS synaptogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:531. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rački N, Morisset D, Gutierrez-Aguirre I, Ravnikar M. One-step RT-droplet digital PCR: a breakthrough in the quantification of waterborne RNA viruses. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014;406:661–667. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7476-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nickless A, Bailis JM, You Z. Control of gene expression through the nonsense-mediated RNA decay pathway. Cell. Biosci. 2017;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13578-017-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gouder L, et al. Three-dimensional quantification of dendritic spines from pyramidal neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2015;1:e53197. doi: 10.3791/53197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Rubeis, S. et al. Delineation of the genetic and clinical spectrum of Phelan-McDermid syndrome caused by SHANK3 point mutations. Mol. Autism 9: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.abouy, L. et al. Dysbiosis of microbiome and probiotic treatment in a genetic model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.05.015 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Bravo JA, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle M, Kiebler MA. Mechanisms of dendritic mRNA transport and its role in synaptic tagging. EMBO J. 2011;30:3540–3552. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zalfa F, et al. The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell. 2003;112:317–327. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phillips M, Pozzo-Miller L. Dendritic spine dysgenesis in Autism Related Disorders. Neurosci Lett. 2015;601:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, et al. Distinct defects in spine formation or pruning in two gene duplication mouse models of autism. Neurosci. Bull. 2017;33:143–152. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexandrov PN, Zhao Y, Jaber V, Cong L, Lukiv WJ. Deficits in the Proline-Rich Synapses-associated Shank3 protein in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders. Fron. Neurol. 2017;8:670. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bey AL, et al. Brain region-specific disruption of Shank3 in mice reveals a dissociation for cortical and striatal circuits in autism-related behaviors. Transl. Psychiatry. 2018;8:94. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Astick, M. & Vanderhaeghen, P. From Human Pluripotent Stem Cells to Cortical Circuits. Current Topics in Developmental Biology129 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Fink, J. J. & Levine, E. S. Uncovering true cellular phenotypes: Using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons to study early insults in neurodevelopmental disorders. Front. Neurol. 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Omole AE, Fakoya AOJ. Ten years of progress and promise of induced pluripotent stem cells: historical origins, characteristics, mechanisms, limitations, and potential applications. Peer J. 2018;6:e4370. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vitrac A, Cloëz-Tayarani I. Induced pluripotent stem cells as a tool to study brain circuits in autism-related disorders. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:226. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0966-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.