Abstract

Faithful chromosome segregation during mitosis is critical for maintaining genome integrity in cell progeny and relies on accurate and robust kinetochore–microtubule attachments. The NDC80 complex, a tetramer comprising kinetochore protein HEC1 (HEC1), NDC80 kinetochore complex component NUF2 (NUF2), NDC80 kinetochore complex component SPC24 (SPC24), and SPC25, plays a critical role in kinetochore–microtubule attachment. Mounting evidence indicates that phosphorylation of HEC1 is important for regulating the binding of the NDC80 complex to microtubules. However, it remains unclear whether other post-translational modifications, such as acetylation, regulate NDC80–microtubule attachment during mitosis. Here, using pulldown assays with HeLa cell lysates and site-directed mutagenesis, we show that HEC1 is a bona fide substrate of the lysine acetyltransferase Tat-interacting protein, 60 kDa (TIP60) and that TIP60-mediated acetylation of HEC1 is essential for accurate chromosome segregation in mitosis. We demonstrate that TIP60 regulates the dynamic interactions between NDC80 and spindle microtubules during mitosis and observed that TIP60 acetylates HEC1 at two evolutionarily conserved residues, Lys-53 and Lys-59. Importantly, this acetylation weakened the phosphorylation of the N-terminal HEC1(1–80) region at Ser-55 and Ser-62, which is governed by Aurora B and regulates NDC80–microtubule dynamics, indicating functional cross-talk between these two post-translation modifications of HEC1. Moreover, the TIP60-mediated acetylation was specifically reversed by sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). Taken together, our results define a conserved signaling hierarchy, involving HEC1, TIP60, Aurora B, and SIRT1, that integrates dynamic HEC1 acetylation and phosphorylation for accurate kinetochore–microtubule attachment in the maintenance of genomic stability during mitosis.

Keywords: mitosis, microtubule, kinetochore, protein acylation, mitotic spindle, chromosomal segregation, HEC1, NDC80 complex, NUF2, TIP60, spindle assembly

Introduction

The core function of mitosis is to equally distribute the duplicated genetic materials into two daughter cells. To achieve this, the accurate segregation of the sister chromatids is the crucial step for faithful mitosis. During mitosis, the connection between chromosomes and spindle microtubules is mediated by a proteinaceous supercomplex, kinetochore, which assembles at the centromere region of chromosome (1–3). NDC80C is a tetramer composed of HEC1/NDC80, NUF2, SPC24, and SPC25 with a 57-nm around dumbbell-shaped structure (4–11). SPC24 and SPC25 bind to Mis12 complex in the inner kinetochore, thus mediating NUF2 and HEC1 anchorage to the kinetochore (11–13). Both HEC1 and NUF2 contain the calponin homology (CH)4 domain at their N termini, through which HEC1 binds to lateral sides of the spindle microtubule. The positively charged and unstructured N-tail (first 80 amino acids; annotated as N80) of HEC1 also binds to microtubule directly and is regulated by Aurora B phosphorylation (14, 15). Dynamic phosphorylation of HEC1 by Aurora A and Aurora B destabilizes kinetochore–microtubule attachment and promotes error correction in early mitosis. The later dephosphorylation of HEC1 is required for chromosome biorientation and silencing of the spindle assembly checkpoint (16–18). It has also been reported that HEC1N80 phosphorylation regulates microtubule dynamics (19, 20). HEC1 also contains an unstructured loop region in the middle, which recruits Ska complex to stabilize kinetochore-attached microtubules. Ska complex is also implicated in promoting the flexibility of NDC80 when connecting with microtubule (21–23). Acetyltransferase TIP60 has been well-studied in ATM activation, p53 activation, PML stabilization for DNA damage response, and genomic stability control (24–28). Recently, our study revealed the function of TIP60 in chromosome stability control during mitosis through acetylating Aurora B (29) and RAN GTPase (30, 31). However, the precise mechanisms underlying accurate kinetochore microtubule attachment remain obscure. Additionally, it was unclear whether and how TIP60 and NDC80C cooperate at the kinetochore during mitosis.

Here, we identified HEC1 as a novel substrate of TIP60 and the acetylation of HEC1 regulates the interaction between flexible HEC1 N-tail and CH domains of HEC1/NUF2 and reduces the phosphorylation of HEC1N80, revealing a potential cross-talk between the two post-translational modifications in orchestrating kinetochore–microtubule attachment during mitosis.

Results

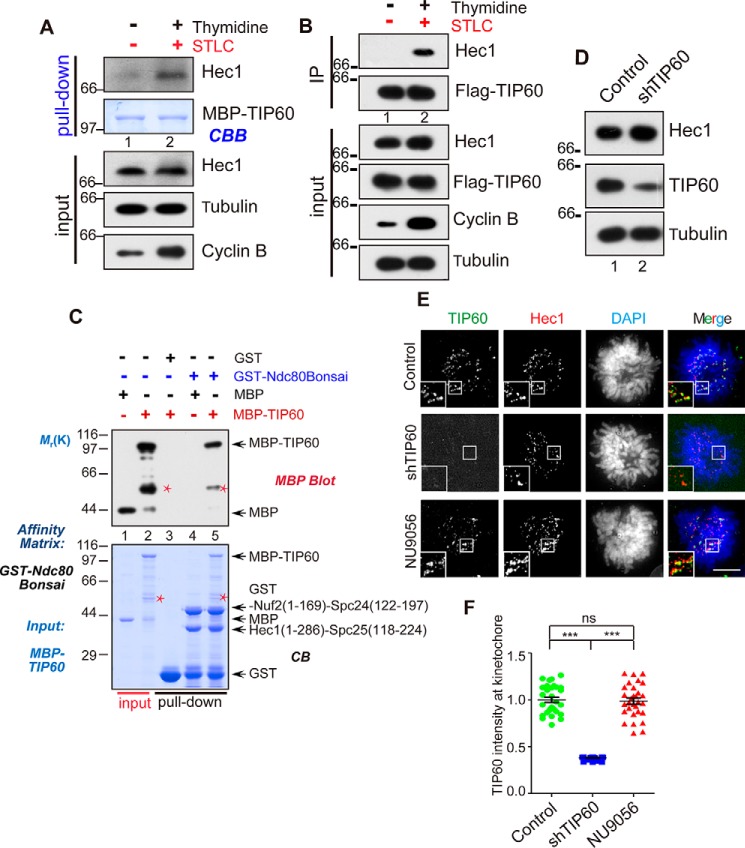

TIP60 is a novel interacting protein of HEC1

Our previous study showed that acetylation of Aurora B kinase by TIP60 protects an activation of Aurora B from dephosphorylation by the PP2A phosphatase to ensure error-free chromosome segregation during cell division (29). Given the fact that kinetochore localization of TIP60 depends on HEC1, we sought to examine whether HEC1 binds to TIP60 directly. We purified MBP-TIP60 as affinity matrix to pull down HEC1 from cell lysate and found that TIP60 specifically binds to HEC1 from the mitotic HeLa cell lysate. Immunoprecipitation studies also validated that endogenous HEC1 and TIP60 form a complex (Fig. 1, A and B). Because HEC1 forms a tetrameric NDC80C together with NUF2, SPC24, and SPC25 to function in kinetochore–microtubule attachment in mitosis (4, 6, 8, 32), we next tested whether TIP60 interacts with NDC80C. GST-tagged engineered “Bonsai” NDC80C (33) was used as an affinity matrix to pull down purified MBP-TIP60. As shown in Fig. 1C, TIP60 binds to NDC80Bonsai. To confirm that the binding of NDC80Bonsai to TIP60 was a direct interaction between TIP60 and HEC1 rather than via other components of NDC80C, MBP-TIP60 was used as an affinity matrix to pull down GFP-HEC1, GFP-NUF2, GFP-SPC24, and SPC25 from cell lysate, respectively. Only GFP-HEC1 was absorbed by the affinity matrix, indicating a specific interaction between HEC1 and TIP60 in Fig. S1A. Thus, TIP60 interacts with HEC1, a major constituent for kinetochore–microtubule attachment.

Figure 1.

TIP60 interacts and co-localizes with HEC1 at kinetochore during mitosis. A, MBP-TIP60–bound agarose beads were used as affinity matrices to absorb HEC1 proteins from HeLa cell lysate, and bound proteins were then analyzed by Western blotting. Cells were synchronized in G1 with thymidine for 17 h and released into mitosis (4 h after thymidine release and treatment with STLC for an additional 4 h). Note that HEC1 from mitotic cells was retained on TIP60 affinity matrix. B, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-TIP60 for 12 h; in lane 2, cells were blocked with thymidine and STLC as in A. Cell lysate were clarified by centrifugation and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitate, after extensive washes, was fractionated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently analyzed by Western blot analyses. C, GST-NDC80Bonsai–bound agarose beads were used as affinity matrices to absorb MBP and MBP-TIP60 proteins. Proteins retained on affinity matrix, after extensive washes, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by CBB staining (bottom) and Western blot analysis with an anti-MBP antibody (top). Red asterisk, nonspecific binding protein. D, HeLa cells were transfected with shTIP60 for 48 h followed by Western blot analyses to evaluate the efficiency of shTIP60. A tubulin blot served as loading control. E, HeLa cells were treated with shTIP60 and NU9056. After 24 h of transfection, cells were synchronized with thymidine for 17 h. After they were released from thymidine for 8 h, cells were fixed and co-stained for TIP60 (green), HEC1 (red), and DNA (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. F, scatter plots of the TIP60 intensity at kinetochore in the cells treated as in E (30 kinetochores). Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars). p values were determined by Student's test. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant.

We then examined the subcellular distribution profile of TIP60 relative to HEC1 to ascertain whether TIP60 activity determines the localization of HEC1 to kinetochore. First, TIP60 protein levels were suppressed by shRNA treatment and were judged by Western blot analyses (Fig. 1D). Next, we examined the relationship of TIP60 and HEC1 in subcellular localization. As shown in Fig. 1E (top), TIP60 and HEC1 co-localized at the kinetochores of HeLa cells, transfected with control shRNA, which is consistent with a previous report (29). However, the localization of HEC1 was altered by neither shRNA-mediated TIP60 suppression nor inhibition by TIP60 inhibitor NU9056, as indicated by the intensity of HEC1 immunofluorescence at the kinetochore (Fig. 1E, row 2 and 3). As a control, TIP60 signal at the kinetochore is abolished by shRNA-elicited knockdown but not by NU9056 treatment (Fig. 1, E and F). Statistical analyses from three separate experiments confirmed that TIP60 is not required for HEC1 localization to the kinetochore (Fig. S1B). Thus, we conclude that TIP60 co-localizes and interacts with HEC1 in mitosis.

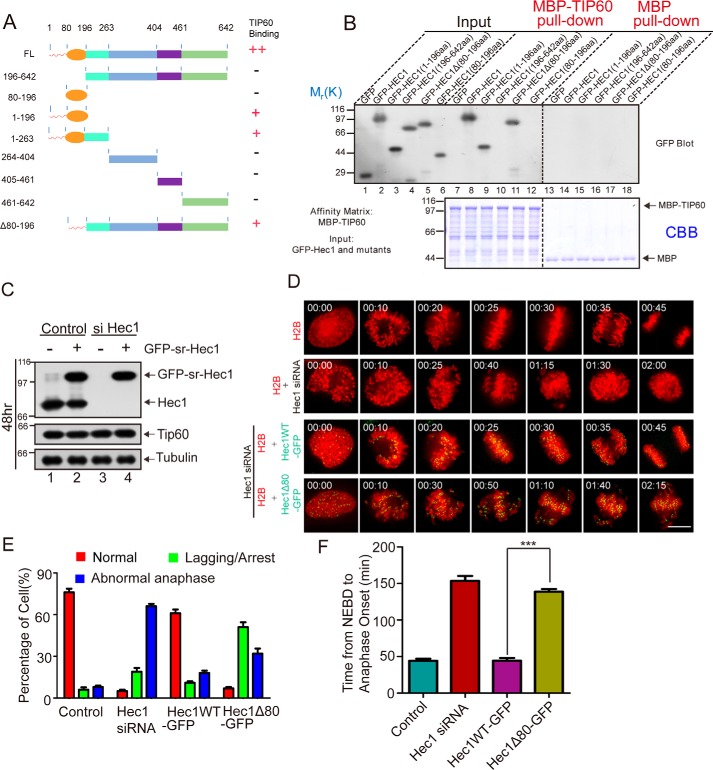

HEC1 interacts with TIP60 via its N-terminal unstructured tail

Having demonstrated an interaction between TIP60 and HEC1, we wanted to identify which domain of HEC1 is responsible for binding to TIP60. A series of deletion mutants of HEC1 tagged with GFP were constructed according to its structural features (33, 34), as illustrated in Fig. 2A. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with GFP-tagged full-length HEC1 and deletion mutants, respectively. Twenty-four hours after the transfection, transfected cells were harvested and lysed for a biochemical assay. After clarification, cell lysates were incubated with MBP-TIP60 affinity beads for the indicated time intervals, followed by three extensive washes before analyses by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. As shown in Fig. S2A, full-length HEC1 and N-terminal fragments HEC1(1–196) and HEC1(1–263) exhibited consistent binding activity to TIP60 acetyltransferase (lanes 9–11). Therefore we conclude that HEC1(1–196) is responsible for interacting with TIP60.

Figure 2.

Characterization of HEC1 interaction with TIP60 in mitosis. A, schematic representation of different HEC1 deletion mutants generated to pinpoint the TIP60-binding activity. B, 293T cells were transfected with GFP, GFP-HEC1, and GFP-tagged HEC1 deletion mutants (aa 1–196, aa 196–642, aa Δ80–196, and aa 80–196), respectively. The proteins retained on MBP and MBP-TIP60 affinity matrix were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and probed by GFP blotting (top), and the inputs of MBP and MBP-TIP60 protein were visualized by CBB staining (bottom). C, HeLa cells were co-transfected with GFP-HEC1 (siRNA-resistant) and control or HEC1 siRNA for 48 h and analyzed by Western blotting. D, HEC1-depleted cells were co-transfected with HEC1 WT or Δ1–80 mutant along with mCherry-H2B. Representative real-time images of each group are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. E, quantification of the phenotype of cells in D. At least 30 cells from three separate experiments per group were analyzed. F, quantification of time intervals from nuclear envelope breakdown to anaphase onset in cells of D. At least 30 cells from three separate experiments per group were analyzed. Statistical significance was examined by two-sided t test. ns, not significant. ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E.

The structure of NDC80C, in particular the tetrameric binding interface, has been well-studied (11, 16, 33). Because HEC1(1–196) contains the N-tail domain (aa 1–80) and CH domain, we generated finer deletion mutants, including HEC1(1–196), HEC1(80–196), and HEC1Δ80–196, and conducted an additional round of pulldown assay. As shown in Fig. 2B and summarized in Fig. 2A, HEC1(1–196) and HEC1Δ80–196 exhibited consistent binding activity to TIP60. To further demonstrate that TIP60 physically binds to the HEC1 N-terminal fragment, we carried out a pulldown assay, using GST-HEC1(1–196) as an affinity matrix. As shown in Fig. S2B (lane 5), TIP60 directly interacts with the HEC1(1–196). Using MBP-TIP60 as affinity matrix, our binding assay showed that HEC1N80 selectively and directly binds to TIP60 (Fig. S2C, lane 3).

After having demonstrated a direct association between TIP60 and HEC1N80 (Fig. S2C), we sought to determine the functional relevance of HEC1N80 during mitosis using live-cell imaging of HeLa cells expressing GFP-HEC1 and GFP-HEC1ΔN80 (deletion mutant in which amino acids from 1 to 80 were removed). To rule out the interference of endogenous HEC1, we suppressed endogenous HEC1 with a siRNA and introduced expression constructs resistant to siRNA treatment. As shown in Fig. 2C, the exogenous GFP-HEC1 protein was expressed at a level similar to endogenous protein (lane 2). In addition, exogenous expression construct GFP-HEC1 was resistant to siRNA treatment (lane 4). As shown in Fig. 2D, suppression of HEC1 by siRNA treatment exhibited a typical chromosome segregation defect, as chromosomes are scattering around the spindle poles with chronic mitotic arrest (row 2). As predicted, expression of GFP-HEC1 rescued the phenotype observed in siRNA treatment, as cells progressed into anaphase onset in 30 min (row 3). However, expression of GFP-HEC1ΔN80 failed to restore accurate chromosome segregation induced by siRNA (bottom panel). Statistical analyses show that cells expressing GFP-HEC1ΔN80 exhibited a high proportion of chromosome alignment defect and abnormal anaphase (Fig. 2E). In addition, these GFP-HEC1ΔN80–expressing cells displayed a prolonged interval from nuclear envelope breakdown to anaphase onset (Fig. 2F), consistent with the phenotypes reported in the literature (14). To examine whether the deletion mutant HEC1ΔN80 altered NDC80C assembly to the kinetochore, the localization of NUF2, SPC24, and HEC1 was evaluated using immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. S2D, kinetochore localization of NUF2 and SPC24 was not remarkably changed. Statistical analyses confirmed that the integrity of the NDC80C and its localization to the kinetochore were not affected by the deletion of the N-terminal tail of HEC1 (Fig. S2E). Therefore, our results are consistent with the previous studies (5, 14–16). In other words, HEC1N80 performed an important function in mitosis, and its deletion resulted in severe mitotic defects. Furthermore, we showed that HEC1N80 interacted with TIP60 (Fig. S2C), which implied that TIP60 might modify HEC1N80 and thus affect the function of HEC1.

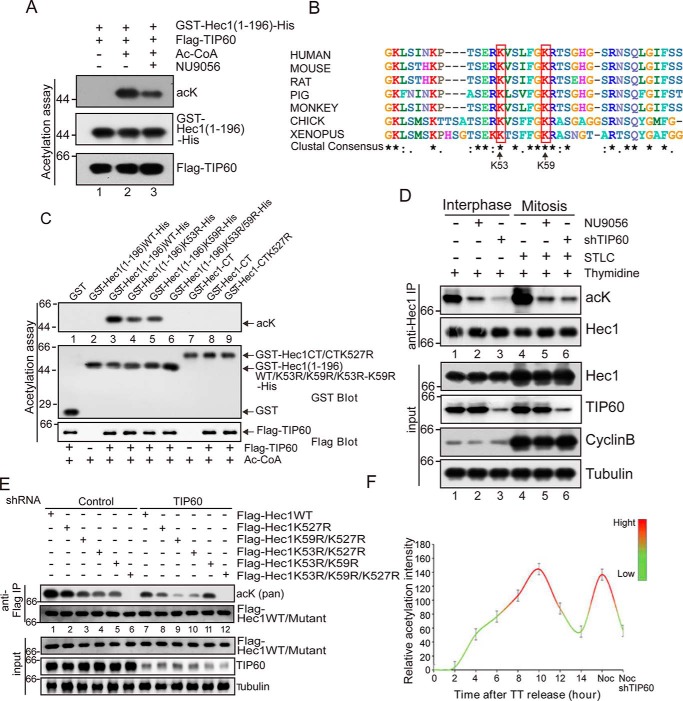

HEC1N80 is a bona fide substrate of TIP60

TIP60 is an important regulator for spindle plasticity and accurate chromosome segregation (29), whereas mounting evidence demonstrated the regulation of HEC1N80 by phosphorylation (35). We hypothesized that TIP60 acetylates HEC1N80, and acetylation of HEC1N80 modulates its interaction with microtubule and NDC80C. To test whether HEC1 is a substrate of TIP60, we carried out an in vitro acetylation assay as we recently reported (29). Specifically, FLAG-TIP60 isolated from HEK293T cells was used to acetylate recombinant GST-HEC1(1–196) in vitro in the presence or absence of Ac-CoA and TIP60 inhibitor NU9056. As shown in Fig. 3A, acetylation of GST-HEC1 was reported by Western blot analyses, which showed that HEC1 is acetylated by TIP60 (lane 2) and that the acetylation is suppressed by TIP60 inhibitor NU9056 (lane 3).

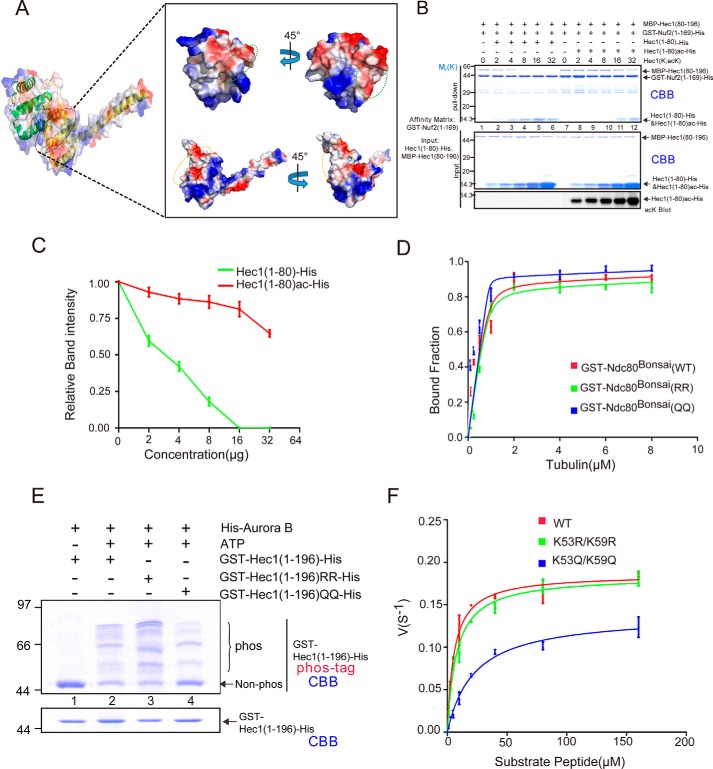

Figure 3.

Lys-53 and Lys-59 on HEC1 are bona fide substrates of TIP60. A, FLAG-TIP60 was incubated with GST-HEC1(1–196)-His in the presence of Ac-CoA for the in vitro acetylation assay. TIP60 specific inhibitor was also added in lane 3. The acetylation levels of HEC1 were analyzed with an anti-acetyllysine antibody (acK). B, sequence alignment of HEC1 from human, mouse, rat, pig, monkey, chicken, and Xenopus. Lys-53 and Lys-59 of human HEC1 were highlighted. *, evolutionary conservation. C, FLAG-TIP60 purified from HEK293T cells was incubated with GST, GST-HEC1(1–196)-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K53R-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K59R-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K53R/K59R-His, GST-HEC1-CT, or GST-HEC1-CTK527R, respectively, in the presence of Ac-CoA for an in vitro acetylation assay. The acetylation levels were analyzed by Western blot analyses using an anti-acetyllysine antibody. HEC1-CT contains aa 222–642. D, HEC1 was immunoprecipitated from HeLa cell lysate with an anti-HEC1 antibody and then analyzed with anti-acetyllysine antibody and HEC1 antibody. In the first three lanes, cells were synchronized in interphase by thymidine treatment for 17 h. In the other three lanes, cells were treated with thymidine for 17 h and released for 8 h and then synchronized in mitosis by STLC for 4 h. In lanes 2 and 5, cells were treated with NU9056. In lanes 3 and 6, cells were transfected with shTIP60 for 24 h before synchronization. E, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged HEC1 or its mutants (K527R, K53R/K527R, K59R/K527R, K53R/K59R, and K53R/K59R/K527R), respectively. Cells were also co-transfected with control or TIP60 shRNA. After 24 h of transfection, anti-FLAG antibody were used to immunoprecipitate FLAG-tagged HEC1 from cell lysate and then analyzed with an anti-acetyllysine antibody and an anti-HEC1 antibody. F, characterization of HEC1 acetylation level during cell cycle. Quantitative analyses of band intensities are shown in Fig. S3E. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

We next sought to pinpoint the acetylation sites of HEC1 that are responsible for TIP60 catalysis. To this end, we first searched the PhosphoSitePlus database and found that HEC1 Lys-53, Lys-59, and Lys-527 sites were acetylated based on mass spectrometric analyses of endogenous HEC1 protein (36). We then conducted sequence alignment analyses to determine the evolutionarily conserved lysines in HEC1 and found that the Lys-53, Lys-59, and Lys-527 sites are conserved (Fig. 3B and Fig. S8). To further confirm whether the above mentioned three sites are substrates of TIP60, we performed an in vitro acetylation assay and found that the acetylation level of HEC1(1–196) was reduced when Lys-53 or Lys-59 was mutated to arginine (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 and 5). However, the acetylation was totally abolished when both Lys-53 and Lys-59 were mutated to arginine (lane 6). In contrast, the C-terminal HEC1(222–642) (HEC1-CT) was not acetylated by TIP60 in vitro (lanes 8 and 9), indicating that Lys-527 is not acetylated by TIP60.

To further determine whether the acetylation in vivo exhibits similar characteristics seen in the in vitro reaction, HeLa cells were synchronized in interphase using thymidine or prometaphase using Eg5 inhibitor STLC followed by siRNA-mediated suppression of TIP60 or treatment with TIP60 inhibitor NU9056. The treated cells were used to generate cell lysates for an anti-HEC1 immunoprecipitation. As shown in Fig. 3D, the level of HEC1 acetylation was higher in prometaphase than in interphase (lane 4 versus lane 1), and the acetylation level was dramatically reduced when cells were treated with NU9056 (lane 1 versus lane 2 and lane 4 versus lane 5) or shTIP60-mediated knockdown (lane 1 versus lane 3 and lane 4 versus lane 6), indicating that HEC1 is acetylated by TIP60 in a cell cycle–dependent manner. To clarify the acetylation sites in vivo, a series of nonacetylatable HEC1 mutants were generated and expressed in HeLa cells in the presence or absence of TIP60 or inhibited TIP60 with NU9056, respectively. These exogenously expressed FLAG-HEC1 mutants were then isolated for Western blot analyses of the acetylation levels. As shown in Fig. 3E and Fig. S3A, no acetylation signal was observed in HEC1 mutant in which all three lysines (Lys-53, Lys-59, and Lys-527) were mutated to arginine (lane 6), indicating that these three sites are responsible for HEC1 acetylation in vivo. The acetylation levels of K527R, K59R/K527R, and K53R/K527R mutants (lane 2 versus lane 8, lane 3 versus lane 9, lane 4 versus lane 10) and HEC1WT (lane 1 versus lane 7) were reduced when cells were co-transfected with shTIP60 or treatment with NU9056, indicating that Lys-53 and Lys-59 were acetylated by TIP60 in vivo. However, the acetylation of HEC1K53R/K59R (lane 5 versus lane 11) was not influenced by shTIP60 or NU9056, indicating that Lys-527 is not the preferred acetylation site of TIP60. Live-cell imaging also revealed no obvious mitotic phenotypes in nonacetylated K527R mutant (Fig. S3, B–D). Thus, we focused on TIP60 substrates of Lys-53 and Lys-59 sites.

Our previous trial experiments showed that HEC1 acetylation levels changed during the cell cycle (Fig. 3D). To study the cell cycle profile of HEC1 acetylation, we collected cells at different time points after release from G1 phase and detected the acetylation level of HEC1. As shown in Fig. S3E, Western blot analyses indicate that the acetylation of HEC1 is a function of TIP60 in mitosis, as suppression of TIP60 abolished the acetylation of HEC1 (lanes 9 and 10). Using HEC1 isolated from synchronized cell lysate with nocodazole (which disassembles the microtubules and blocks cells in prometaphase), our Western blot analyses show that acetylation of HEC1 reached a high level at prometaphase (lane 9). The blot analyses of relative intensity of acetylated HEC1 over HEC1 protein level demonstrated that the acetylation level of HEC1 is highest in prometaphase cells (Fig. 3F). Thus, we conclude that the acetylation of HEC1 is dynamic and peaks in mitosis.

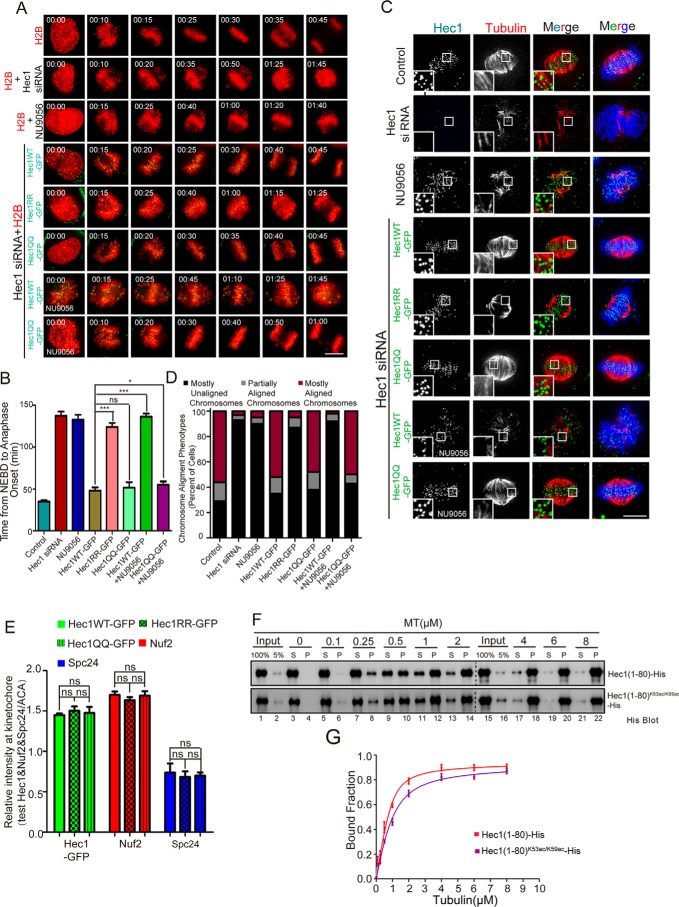

HEC1 acetylation promotes robust kinetochore–microtubule attachment

To probe whether the acetylation of Lys-53 and Lys-59 exhibits any physiological function in mitosis, we carried out real-time analyses to examine chromosome segregation dynamics using mCherry-H2B–expressing HeLa cells. Endogenous HEC1 was knocked down, and exogenous GFP-tagged siRNA-resistant and nonacetylatable HEC1RR (K53R/K59R) or acetylation-mimicking HEC1QQ (K53Q/K59Q) was expressed, respectively (Fig. 4A). Western blot analyses confirmed that the levels of various exogenously expressed GFP-HEC1 proteins (WT, GFP-HEC1RR, and GFP-HEC1QQ) were comparable in the presence of HEC1 siRNA treatment (Fig. S4A). As shown in Fig. 4A, exogenously expressed GFP-HEC1WT and GFP-HEC1QQ successfully rescued the phenotypes seen as mitotic arrest and abnormal anaphase resulting from the knockdown of endogenous HEC1. However, nonacetylatable GFP-HEC1RR failed to rescue the phenotype deficient in endogenous HEC1 (Fig. S4B). Quantitative analyses of the intervals from nuclear envelope breakdown to anaphase, as shown in Fig. 4B, indicate that there was no apparent difference among cells expressing HEC1WT and HEC1QQ. However, cells expressing HEC1RR exhibited mitotic delay in mitosis (Fig. 4, A and B). Interestingly, the exogenous GFP-HEC1QQ could partially rescue the mitotic defects caused by TIP60 acetyltransferase inhibitor NU9056 (Fig. 4, A (row 8) and B). However, the exogenous GFP-HEC1WT could not rescue the mitotic defects caused by NU9056 (Fig. 4, A (row 7) and B). These results suggested that the acetylation of HEC1 on Lys-53/Lys-59 by TIP60 involves precise mitosis.

Figure 4.

HEC1 acetylation promotes robust kinetochore–microtubule attachment. A, real-time analyses of chromosome segregation in the absence of HEC1, TIP60, and acetylation-mimicking mutants of HEC1. HeLa cells were transfected to express mCherry-H2B and GFP-HEC1 (WT and mutants). B, quantitative analyses of time intervals from nuclear envelope breakdown to the beginning of anaphase in HeLa cells. 30 cells were analyzed for each group. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was tested by two-sided t test: *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. C, immunofluorescence images of cells treated with siHEC1, NU9056, or exogenously expressing HEC1 mutants with a cold-induced microtubule depolymerization. Scale bar, 10 μm. D, quantification of chromosome alignment phenotypes in C. HeLa cells with mostly aligned chromosomes (purple) exhibited <5 chromosomes off of a well-formed metaphase plate, cells with partially aligned chromosomes (gray) exhibited 5–10 chromosomes off of a metaphase plate, and cells with mostly unaligned chromosomes (black) exhibited either no chromosome alignment or >10 chromosomes off of a metaphase plate. For each condition, at least 90 cells were scored. E, quantification of the immunofluorescence intensity of GFP-HEC1 (WT and mutants), NUF2, and SPC24 staining at kinetochores, normalized to the ACA signal, respectively. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars). from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was examined by two-sided t test. ns, not significant; ***, p < 0.001. F, HEC1(1–80)-His and HEC1(1–80)K53ac/K59ac-His were precipitated with increasing amounts of taxol-stabilized microtubules. The supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions of HEC1(1–80)-His were blotted with the His antibody. G, plot of quantifications of the microtubule co-sedimentation assay with HEC1(1–80)-His and HEC1(1–80)K53ac/K59ac-His. Fractions of MT-associated HEC1(1–80)-His proteins were plotted against MT concentrations. Data were fitted with the full quadratic binding equation in GraphPad Prism. Error bars, S.D. (n = 3 independent experiments).

Because HEC1 exhibits critical importance in kinetochore–microtubule binding and spindle assembly checkpoint signaling (33, 34, 37), we sought to examine whether HEC1 acetylation modulates the kinetochore–microtubule attachment in mitosis. To this end, HeLa cells were treated with HEC1 siRNA to suppress endogenous HEC1 protein, followed by expressing siRNA-resistant exogenous GFP-HEC1WT, GFP-HEC1RR, or GFP-HEC1QQ. The siRNA-treated cells and exogenous GFP-HEC1WT–, GFP-HEC1RR–, or GFP-HEC1QQ–expressing cells deficient in endogenous HEC1 were subjected to cold treatment followed by immunofluorescence staining to check the stability of kinetochore–microtubule attachment. As shown in Fig. 4C, suppression of endogenous HEC1 resulted in destabilization of spindle (second panel from the top). In addition, inhibition of TIP60 by NU9056 also attenuated spindle microtubule stability. Significantly, expression of exogenous GFP-HEC1WT or HEC1QQ rescued the spindle destabilization phenotype, although HEC1QQ-expressing cells exhibited hyperstabilized spindle (row 6). Of interest, TIP60 inhibitor NU9056 did not attenuate this hyperstabilization with GFP-HEC1QQ (Fig. 4C, bottom panel), but reduced the hyperstabilization with GFP-HEC1WT (Fig. 4C, second panel from the bottom). Statistical analyses show that exogenously expressing GFP-HEC1WT and HEC1QQ proteins in endogenous HEC1-suppressed cells restored the chromosome alignment (Fig. 4D). However, the exogenous HEC1RR–expressing cells exhibited high proportion of unaligned chromosomes, similar to cells treated with siHEC1 or TIP60 chemical inhibitor. The results suggest that acetylation of HEC1 promotes kinetochore–microtubule attachment during mitosis.

There are several ways to explain the above results: 1) acetylation of HEC1 could alter the localization of NDC80 components; 2) acetylation may regulate the binding affinity between HEC1 and microtubule; 3) acetylation may modulate the intramolecular interaction of NDC80 components; or 4) acetylation affects the phosphorylation of HEC1N80 and thus regulates NDC80C–microtubule attachment. To delineate the precise mechanisms underlying acetylation of HEC1 in mitosis, we first assessed whether acetylation of HEC1 modulates the location of NDC80C to the kinetochore. Using immunofluorescence staining, we found that acetylation did not apparently alter the localization of NDC80C components NUF2 and SPC24 to the kinetochore (Fig. S4, C and E). To determine whether acetylation modulates the direct binding of NDC80C to microtubules, we sought to perform an in vitro microtubule co-sedimentation assay using chemically acetylated HEC1 peptide HEC1N80-K53ac/K59ac-His and nonacetylated HEC1N80-His. To perform quantitative analyses of acetylation-elicited binding characteristics, we first determined a linear region of HEC1 peptide detected by chemiluminescence as described previously (e.g. see Refs. 9 and 37). As shown in Fig. S4D, the linear region for quantifying HEC1 peptide is between 0.05 and 0.5 μm.

Next, we carried out a co-sedimentation assay using HEC1 peptide (HEC1N80-K53ac/K59ac-His and HEC1N80-His; 200 nm) incubated with preformed microtubules. The Western blot analyses show that the HEC1 peptides were co-sedimented with taxol-stabilized microtubules in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4F, lanes 6–14). Neither protein was pelleted in the absence of microtubules (top and bottom panels; lane 4). Linear transformation of the densitometric measurements into GraphPad Prism version 5 was used to fit the curves and calculate a dissociation constant (Kd) of ∼0.18 ± 0.05 μm for nonacetylated HEC1 binding to microtubule and a Kd of ∼0.42 ± 0.09 μm for acetylated HEC1 (Fig. 4G). Thus, we conclude that the acetylation decreased the binding affinity of HEC1N80 to microtubules. However, acetylation of HEC1 has no effect on the localization of NDC80C components.

Acetylation eliminates HEC1N80 interference to interaction of NUF2-HEC1 CH domain and weakens the phosphorylation of HEC1N80

To test whether the acetylation of HEC1N80 regulates the intramolecular interaction of HEC1–NUF2, GST-NUF2(1–169)-His was used as an affinity matrix to isolate GFP-HEC1 and its mutants (GFP-HEC1RR and GFP-HEC1QQ) from HEK293T cell lysate, respectively. In addition, we performed a reciprocal pulldown assay by using GST-HEC1(1–196)-His and its mutants (HEC1(1–196)RR and HEC1(1–196)QQ) as affinity matrix to absorb NUF2. Both experiments showed that HEC1QQ has a higher binding affinity to the CH domain of NUF2 than HEC1WT or HEC1RR (Fig. S5, A and B). In addition, when HeLa cells were blocked in interphase or prometaphase and the activity of endogenous TIP60 was inhibited by its specific inhibitor NU9056 or shTIP60, the binding of endogenous HEC1 to recombinant GST-NUF2(1–169)-His was attenuated in a pulldown experiment (Fig. S5, C and D). Moreover, an immunoprecipitation assay indicated that FLAG-HEC1(1–196)QQ had a higher binding affinity to NUF2 in vivo than FLAG-HEC1(1–196) and FLAG-HEC1(1–196)RR (Fig. S5E). Together, the data showed that acetylation of HEC1 by TIP60 at Lys-53 and Lys-59 can promote the interaction of HEC1–NUF2 CH domain.

By structural analyses of the HEC1(80–196)–NUF2(1–169) interface on the NDC80C structure, we found that the electrostatic surfaces of some areas of interest in both HEC1(80–196) (indicated by a green circle) and NUF2(1–169) (indicated by an orange circle) were negatively charged, as shown in Fig. 5A. However, HEC1N80 has a strong positively charged surface based on a predicted model (Fig. S5, F and G), which may have electrostatic interaction between HEC1N80 and HEC1(80–196) or NUF2(1–169), and such interaction may affect the interface of HEC1–NUF2 CH domain. More importantly, our pulldown assay ensured that HEC1N80 can interact with both HEC1(80–196) and NUF2(1–169) (Fig. S5, H and I), and another pulldown and competition binding assay in vitro supported our hypothesis that HEC1N80 interferes with the interaction between HEC1(80–196) and NUF2(1–169) (Fig. S5 (J and K) and Fig. 5 (B and C)). As described earlier, a linear region of anti-SPC25 Western blotting was determined (Fig. S5L). We then carried out a co-sedimentation assay using acetylation-mimicking mutants of NDC80Bonsai proteins incubated with preformed microtubules. The Western blotting of SPC25 in Fig. S5M shows that the NDC80Bonsai (1 μm) proteins (WT, RR, and QQ) were co-sedimented with taxol-stabilized microtubules in a dose-dependent manner. Neither protein was pelleted in the absence of microtubules (Fig. S5M, lane 4).

Figure 5.

Acetylation of HEC1N80 modulates the interaction of NUF2-HEC1 CH domain and weakens the phosphorylation of HEC1N80. A, surface views of HEC1(80–196) and NUF2(1–169), colored by electrostatic potential. B, GST-NUF2(1–169)-His–bound agarose beads were used as affinity matrices to pull down MBP-HEC1(80–196) in a competitive binding experiment with HEC1(1–80)-His or HEC1(1–80)ac-His in increased doses (0–32 μg). The results were visualized by CBB staining (top). C, quantification of binding intensity between GST-NUF2(1–169) and MBP-HEC1(80–196) in the presence of different concentrations of HEC1(1–80)-His (green curve) or HEC1(1–80)ac-His (red curve) from the experiment shown in B. D, plot of quantifications of the microtubule co-sedimentation assay with WT NDC80Bonsai complex and with the K53R/K59R and K53Q/K59Q NDC80Bonsai mutant in Fig. S5M. Fractions of MT-associated NDC80Bonsai proteins were plotted against MT concentrations. Data were fitted with the full quadratic binding equation in GraphPad Prism. Error bars, S.D. (n = 3 independent experiments). E, to examine the phosphorylation states of GST-HEC1(1–196)-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K53R/59R-His, and GST- HEC1(1–196)K53Q/K59Q-His, 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE in the absence (bottom) or presence (top) of the polyacrylamide-bound Mn2+-Phos-tagTM ligand (25 mm) was performed. F, determination of kinetic parameters of HEC1WT, HEC1K53R/K59R, and HEC1K53Q/K59Q. The velocities of the kinase assay toward the 15-mer substrate peptide at varying concentrations were measured by the AmpliteTM universal fluorimetric kinase assay kit. Data from three independent experiments were analyzed in GraphPad Prism and fitted with the Michaelis–Menten equation to extract the kinetic parameters. Bars, means ± S.D. (error bars).

Linear transformation of the densitometric measurements into GraphPad Prism version 5 was used to fit the curves and calculate a Kd of 0.01 ± 0.01 μm for acetylation-mimicking NDC80Bonsai (QQ). The values for WT and RR mutant NDC80Bonsai are 0.05 ± 0.02 and 0.06 ± 0.03 μm, respectively (Fig. S5M and Fig. 5D). Taken together, these studies indicate that HEC1 acetylation at Lys-53 and Lys-59 promotes the association of NDC80 complex with the microtubules.

Mounting evidence demonstrated that the N terminus of HEC1 (N80) is also regulated by Aurora B kinase, and the phosphorylation of HEC1N80 plays an important role in kinetochore–microtubule attachment. The phosphorylation sites identified at N80 include Ser-4, Ser-5, Ser-8, Ser-15, Ser-44, Thr-49, Ser-55, Ser-62, and Ser-69 (e.g. see Refs. 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 33, 38, and 39). Because some of these sites are close to the Lys-53 and Lys-59, we hypothesize that the acetylation identified in this study may interact with some of the aforementioned phosphorylation sites. To test this hypothesis, we compared the phosphorylation characteristics of acetylation-mimicking HEC1 with those of unacetylatable HEC1. As shown in Fig. 5E, we found that the phosphorylation of HEC1(1–196)K53Q/K59Q by Aurora B was clearly weaker than that of WT and RR mutants judged by a Phos-tag SDS-PAGE assay. This result implied that acetylation of HEC1N80 may attenuate the phosphorylation of the N terminus of HEC1. Interestingly, Lys-53 and Lys-59 are just located at the −2 or −3 position of Ser-55 and Ser-62, so we sought to examine whether the acetylation on Lys-53 and Lys-59 affects the phosphorylation of Ser-55 and Ser-62. By using the in vitro enzyme kinetics experiment with FLAG-Aurora B and the 15 amino acid peptides containing Ser-55, Lys-53, Lys-59, and Ser-62 as well as the corresponding RR and QQ mutants respectively, we analyzed and compared the Km (Michaelis constant) and Kcat of the three peptides, as shown in Fig. 5F and Fig. S5 (N and O), and the results showed that the QQ mutation attenuated the phosphorylation of Ser-55 and Ser-62 by Aurora B. The experimental results of in vitro phosphorylation were in line with our in vivo cell experiments (Fig. 4, A and B). In other words, the inhibition of TIP60 by NU9056 or siRNA will result in a decrease of HEC1 acetylation, which further leads to an increase of HEC1 phosphorylation and thus destabilizes the kinetochore–microtubule connection. On the other hand, exogenously expressed acetylation-mimicking mutants HEC1K53Q/K59Q weaken the HEC1 phosphorylation by Aurora B and in return stabilize the kinetochore–microtubule connection and promote a normal mitosis process.

In summary, HEC1N80 may transiently interact with HEC1 CH domain and NUF2 CH domain before or during the assembly of NDC80C (Fig. S5, H and I). The acetylation of HEC1 Lys-53/Lys-59 may reduce such intramolecular interactions but enhance the intermolecular interactions of the HEC1–NUF2 CH domain of NDC80C. In addition, HEC1 Lys-53 and Lys-59 acetylation may weaken the phosphorylation of Ser-55 and Ser-62 of HEC1 by Aurora B, which in turn strengthens the kinetochore–microtubule attachment.

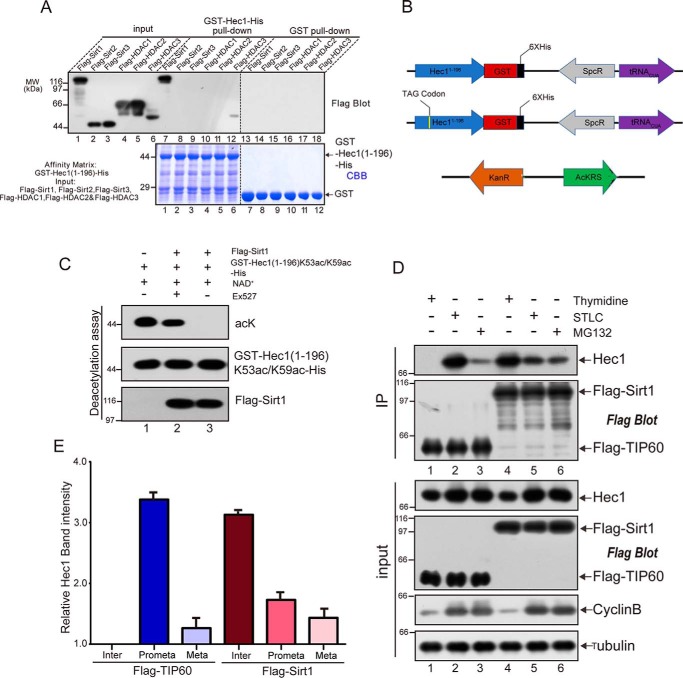

Sirt1 binds and catalyzes the deacetylation of HEC1 at Lys-53/Lys-59

Because the integrity of NDC80C is essential for chromosome segregation, we reason that the HEC1 acetylation is very dynamic to govern the accurate attachment of NDC80C–microtubule. To uncover dynamic acetylation of HEC1 in mitosis, we sought to search for the enzyme that deacetylates HEC1 at Lys-53/Lys-59. We used HEC1(1–196) as affinity matrix to pull down different deacetylases, including Sirt1, Sirt2, Sirt3, HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3, expressed in HEK293T cells (40, 41). Interestingly, only Sirt1 specifically binds to HEC1(1–196) based on the pulldown assay (Fig. 6A, lane 7). To further determine whether Sirt1 could deacetylate HEC1, we employed a genetically encoded method, developed by Jason Chin and adopted in our laboratory (42, 43), to produce site-specific recombinant acetylated HEC1 on Lys-53 and Lys-59 (schematic illustration shown in Fig. 6B and Fig. S6 (A and B)). As shown in Fig. 6C, our in vitro deacetylation assay demonstrated that Sirt1 deacetylated the recombinantly acetylated HEC1(1–196), and the deacetylation reaction was inhibited by Sirt1 chemical inhibitor Ex527 (lane 3, top).

Figure 6.

Sirt1 binds and deacetylates HEC1. A, 293T cells were transfected to express FLAG-Sirt1, FLAG-Sirt2, FLAG-Sirt3, FLAG-HDAC1, FLAG-HDAC2, or FLAG-HDAC3 proteins, respectively. Clarified cell lysate was prepared 24 h after the transfection, followed by incubation with GST– or GST-HEC1(1–196)–bound agarose beads for 4 h. After extensive washes, the GST– and GST-HEC1(1–196)–bound agarose beads were boiled in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer followed by SDS-PAGE analyses stained with CBB staining and probed by anti-FLAG blotting (top). B, diagram of plasmid combinations used to produce WT or recombinant acetylated HEC1 protein (K53ac/K59ac-HEC1(1–196)) in E. coli. C, the recombinant acetylated GST-HEC1K53/59-His protein was incubated with NAD+ (lane 1), FLAG-Sirt1 + NAD+ + Ex527 (lane 2), or FLAG-Sirt1 + NAD+ (lane 3). After incubation at 30 °C for 2 h, the samples were analyzed with an anti-acetyllysine antibody (acK) and HEC1 antibody by Western blot analyses. D, 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-TIP60 (lanes 1–3) or FLAG-Sirt1 (lanes 4–6). In lanes 1 and 4, cells were blocked in interphase. In lanes 2 and 5, cells were blocked in prometaphase with STLC for 16 h. In lanes 3 and 6, cells were blocked in metaphase with MG132. Cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and probed by anti-HEC1 and anti-FLAG blotting. E, quantification of HEC1-binding intensity with TIP60 and Sirt1 shown in D. Data represent mean ± S.E. (error bars) from three independent experiments.

To probe how the acetyltransferase and deacetylase orchestrate HEC1 acetylation, we blocked cells in three different cell cycle stages (interphase, prometaphase, and metaphase, respectively), followed by immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG antibody. As shown in Fig. 6D, the binding efficiency of HEC1 to TIP60 is strong in prometaphase and weak in metaphase, whereas the binding of HEC1 to Sirt1 is strong in interphase but weak in metaphase. Quantitative analyses of three independent experiments confirmed this observation (Fig. 6E). In fact, this result was consistent with the HEC1 acetylation levels during cell cycle (Fig. 3F and Fig. S3E).

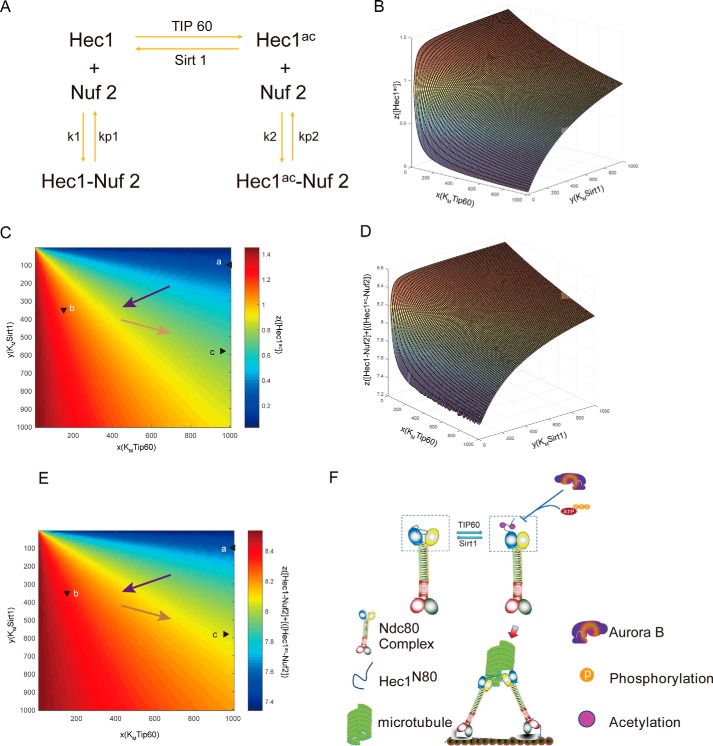

Mathematical modeling of dynamic acetylation of HEC1 in mitosis

To computationally model the dynamic acetylation and deacetylation on HEC1 relative to the regulation of kinetochore–microtubule attachment, we constructed a chemical equilibrium model to make quantitative analyses. As shown in Fig. 7A, TIP60 catalyzes the acetylation reaction and Sirt1 controls the deacetylation reaction; both acetylated HEC1 (HEC1ac) and nonacetylated HEC1 could form a complex with NUF2 but with different equilibrium constants. Given the changing of binding affinity of TIP60 and Sirt1 to HEC1 in different phases illustrated above (Fig. 6D), we sought to analyze how the HEC1 acetylation level and amount of HEC1–NUF2 complex changed. Thus, we supposed the amount of HEC1 as a constant, including HEC1, HEC1ac, HEC1–NUF2, and HEC1ac–NUF2, and the amount of NUF2 as a constant, including NUF2, HEC1–NUF2, and HEC1ac–NUF2. We used the Michaelis–Menten equation to describe the enzymic catalytic reaction, and we took the Michaelis constant Km of the TIP60- and Sirt1-catalyzed reaction as the variable, which could reflect the binding affinity of TIP60 and Sirt1 to HEC1 (44). The functions were thus listed as in Fig. S7A. To analyze the steady-state solution of the equation with the change of Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60), we set up the reaction rates to be zero and generated the function about the concentration of HEC1ac and HEC1–NUF2 complex ([HEC1–NUF2] + [HEC1ac–NUF2]) (Fig. S7B). Then we performed quantitative analyses of the trend of [HEC1ac] in different cell phases. Because ∼60% of all Km values are in the range of 10–1000 μm (45), we set the Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60) range as 10–1000 μm. Then we plotted the curved surface of [HEC1ac] versus Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60) (Fig. 7B); with the rise of TIP60-binding affinity and the drop of Sirt1-binding affinity, the [HEC1ac] significantly rises. To further analyze the [HEC1ac] in a different phase, we quantified the binding affinity of TIP60 and Sirt1 from the result in Fig. 6D and used this to estimate the Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60). We assumed in the interphase, when TIP60 had the lowest binding affinity and Sirt1 had the highest binding affinity, the Km(TIP60) = 1000 μm and Km(Sirt1) = 100 μm; thus, we estimated the value of Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60) in prometaphase and metaphase by assuming that Km had an inverse relation with binding affinity quantified from Fig. 6D. We then marked the [HEC1ac] in different phases in a two-dimensional picture (Fig. 7C). It showed that HEC1ac level rose from interphase to prometaphase and dropped in metaphase, consistent with our experiments (Fig. 3F). To analyze how binding affinity of TIP60 and Sirt1 influence the formation of HEC1–NUF2 complex, we plotted the curved surface of ([HEC1–NUF2] + [HEC1ac–NUF2]) versus Km(Sirt1) and Km(TIP60) (Fig. 7D) and marked the state in different cell phase (Fig. 7E), with a similar tendency of [HEC1ac]. Thus, with the high binding affinity of TIP60 and significantly reduced binding affinity of Sirt1, the acetylation level of HEC1 was significantly elevated and elicited the chemical equilibrium's shift toward the stabilization of HEC1–NUF2 complex and promoted highly stable attachment to microtubules.

Figure 7.

Mathematical modeling of HEC1 acetylation dynamics and regulation. A, diagram of chemical equilibrium model. B–E, acetylated HEC1 concentration (B and C) and total HEC1–NUF2 complex concentration (D and E) versus Km (TIP60) and Km (Sirt1). In C and E, the statuses in prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase are labeled a, b, and c, respectively. For the sake of simplification, we set [Ntotal] = [Htotal] = 10, [T] = [S], kT = kS, k1/kp1 = 1, k2/kp2 = 4. F, model for TIP60 and Sirt1 in regulating kinetochore–microtubule attachment. The model illustrates a novel cross-talk regulated by TIP60-mediated acetylation at Lys-53 and Lys-59 and Aurora B–governed phosphates at Ser-55 and Ser-62 of HEC1N80.

Discussion

The NDC80C of the outer kinetochore is responsible for the connection to microtubules, and the stability of this connection is regulated by various post-translational modifications. Previous studies demonstrate that Aurora B phosphorylates the HEC1N80 to destabilize the microtubule–kinetochore attachment (16–20). In this study, HEC1 was demonstrated to be a cognate substrate of acetyltransferase TIP60 at Lys-53 and Lys-59 of HEC1N80 during mitosis. This TIP60-elicited acetylation plays a regulatory role in the intermolecular interactions between HEC1 and NUF2 CH domain and accurate chromosome segregation by inhibiting intramolecular interaction between N80 and the CH domain. Interestingly, the acetylation of N80 weakens the phosphorylation of Ser-55 and Ser-62 at HEC1 by Aurora B, suggesting an additional layer of cross-talk between TIP60 signaling and Aurora B effectors beyond the direct TIP60–Aurora B interaction (29). These results presented here establish a previously uncharacterized regulatory mechanism governing NDC80C plasticity control through acetylation-mediated regulation of the CH domain and cross-talk between acetylation and phosphorylation of HEC1. We developed a new mathematical model to account for accurate attachment of NDC80C–microtubule via dynamic post-transcriptional modifications (Fig. 7F).

Previous studies demonstrated that the phosphorylation of HEC1N80 region weakens the NDC80C–microtubule attachment to enable a prompt correction of aberrant connections, such as syntelic and merotelic attachments. The dephosphorylation process is spatiotemporally coordinated with the phosphorylation to promote the NDC80C–microtubule attachment in a precisely controlled manner (14, 15, 19, 20). Thus, the excitement and challenge ahead is to illuminate the spatiotemporal characteristics underlying the cross-talk between the TIP60-elicited acetylation and Aurora B–mediated phosphorylation of HEC1N80. Recently, two independent studies from the Yu (46) and Kops (47) groups, respectively, demonstrated that phosphorylation of the HEC1N80 enhanced binding of Mps1 to NUF2 through the MR fragment. Mps1 and microtubules bind NDC80C competitively and thus monitored kinetochore–microtubule attachment (46, 47).

It is worth noting that the HEC1N80 acetylation characterized here exhibits a context-dependent function relative to NDC80C–microtubule interaction. Using two independent analyses (e.g. see Refs. 33 and 46), our calculation indicated that the TIP60-elicited acetylation weakens the affinity of HEC1N80 for microtubules in isolation. On the other hand, the acetylation of HEC1N80 by TIP60 strengthens the interaction of Bonsai complex with microtubules.

We believe the regulatory function of acetylation of HEC1N80 in Bonsai complex reflects and is consistent with the role of TIP60–NDC80C interaction in mitosis. It is also interesting to note that the acetylation cross-talks with the Aurora B–elicited phosphorylation. From our enzymatic studies, it appears that the acetylation-mimicking HEC1-QQ mutant exhibits an altered affinity with kinase, and likely the kinetics of ADP generation and/or release or the Km value of kinase to ATP was affected by the QQ mutant. Further characterization of the structure–activity relationship of NDC80C acetylation and phosphorylation will yield information helpful for better understanding of dynamic and complex kinetochore–microtubule interactions in mitotic control. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that HEC1N80 plays an important role in regulating NDC80C function, and the dynamic post-translational modifications of HEC1N80, including acetylation and phosphorylation, provide a homeostatic control of NDC80C activity by tuning HEC1N80 activity for accurate chromosome segregation in mitosis.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the acetylation of HEC1, by TIP60, promotes the dynamic and precise assembly of functional N-terminal NDC80C and has cross-talk with phosphorylation necessary for the robust kinetochore–microtubule attachment to ensure chromosome stability in mitosis.

Experimental procedures

Plasmid construction

Standard mutagenesis was carried out to generate nonacetylation and acetylation- mimicking HEC1 mutants using a PCR-based, site-directed mutagenesis kit from Vazyme (C212) according to the manufacturer's instructions. GST-tagged HEC1 and NUF2 truncations (HEC1(1–196), HEC1(80–196), HEC1Δ(80–196), and NUF2(1–169)) were generated by inserting the corresponding PCR-amplified fragments into the pGEX-6P-1 vector via a recombination reaction by Vazyme. His-tagged HEC1-CT (HEC1(222–642)) was generated by inserting the corresponding PCR-amplified fragments into the pET28a vector via recombination reaction. HEC1 siRNA (AAGTTCAAAAGCTGGATGATCTT), synthesized by GenePharma, has been described previously (48). ACKRS3 and pCDF-pylT plasmids were gifts from the laboratory of J. Chin. HEC1(1–196)-GST-His-INbox was constructed by inserting HEC1(1–196) downstream of two adjacent T7 promoters in pCDF-pylT. The corresponding AAA codon in HEC1(1–196)-GST-His was mutated to TAG to generate HEC1(1–196)-K53TAG/K59TAG-GST-His. All plasmids used were verified by sequencing (Invitrogen).

Cell culture and drug treatments

HeLa and HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively; Invitrogen). Thymidine was used at 2 mm, nocodazole at 100 ng/ml, STLC at 10 μm, MG132 at 20 μm, TIP60-specific inhibitor NU9056 at 20 μm, and Sirt1 inhibitor Ex527 at 10 μm.

Protein expression and purification

The acetylated protein was produced from Escherichia coli as described previously (42, 43). Briefly, E. coli strain Rosetta (DE3) was transformed with pACKRS and HEC1(1–196)-K53TAG/K59TAG-GST-His plasmids simultaneously. The bacteria were cultured in lysogeny broth medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and spectinomycin (50 μg/ml), and 10 mm acetyllysine and 20 mm nicotinamide were added until A600 reached 0.7. After a 30-min incubation, 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to induce protein expression at 37 °C for 4 h.

The plasmids of other GST- or MBP-tagged protein were transformed into E. coli strain BL21 or Rosetta (DE3), and 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to induce protein expression when A600 reached 0.6, with shaking overnight at 16 °C. Protein purification was carried out as described previously (49, 50). Briefly, the GST fusion proteins were purified using GSH-agarose chromatography, the MBP-tagged proteins were purified using amylose beads, and histidine-tagged proteins were purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid–agarose beads (Qiagen). HEC1N80-His and HEC1N80K53ac/K59ac-His were synthesized by GL Biochem Ltd.

Pulldown assays

MBP, MBP-tagged proteins, GST, or GST-tagged protein–bound agarose beads were incubated with soluble proteins in TGE buffer or with cell lysate at 4 °C for 4 h. After washing with pulldown wash buffer three times (5 min each time), the resins were boiled in SDS sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by Western blotting or CBB staining. TGE buffer contained 50 mm Tris-Cl, 50 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, and 5% glycerol, and pH was adjusted to 7.9.

Immunoprecipitation

293T cells were transfected with plasmids of FLAG-tagged proteins for 24 h, and then cells were collected and lysed in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) supplemented 1 mm DTT, protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and DNase. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min, supernatant was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 beads at 4 °C for 4 h. Then beads were washed two times with PBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 and one time with PBS. Then beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot analyses or CBB staining.

In vitro acetylation assay

The in vitro acetylation assay was described previously (29, 51). Briefly, purified FLAG-TIP60 was incubated with GST-HEC1(1–196)-His in 40 μl of HAT buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50% glycerol, 5 mm DTT, 0.5 mm EDTA) containing 1 mm acetyl-CoA for 2 h at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 5× sample buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were analyzed by Western blot analyses.

In vitro deacetylation assay

FLAG-tagged Sirt1 (2 μg) was incubated with recombinant Lys-53/Lys-59–acetylated GST-HEC1(1–196)-His (0.2 μg) in the presence of 0.5 mm NAD+ in the deacetylase buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 200 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, protease inhibitor mixture, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture) for 2 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding SDS sample buffer followed by boiling at 95 °C for 5 min.

In vitro Aurora B kinase assay

Purified recombinant GST-HEC1(1–196)-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K53R/K59R-His, GST-HEC1(1–196)K53Q/K59Q-His, and His-Aurora B were incubated in kinase buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT) supplemented with 100 μm ATP and protease mixture inhibitor for 20 min at 30 °C. The kinase reactions were stopped by the addition of 5× sample buffer (10% SDS, 0.5% bromphenol blue, 50% glycerol, 1 m DTT) before being resolved by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE (47) (10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE with the polyacrylamide-bound Mn21-Phos-tagTM ligand (25 mm)) (52).

Kinase kinetics characterization

FLAG-Aurora B kinases were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay using the 15-mer substrate peptide (WT, ERKVSLFGKRTSGHG; RR, ERRVSLFGRRTSGHG; QQ, ERQVSLFGQRTSGHG) and ATP as the substrates and the ADP assay buffer provided by the AmpliteTM universal fluorimetric kinase assay kit *Red Fluorescence* (AAT Bioquest) as the kinase buffer. The produced ADP was quantified using the AmpliteTM universal fluorimetric kinase assay kit according to the manufacturer's manuals (53–56). The velocity of phosphorylation at a certain concentration of ATP and substrate peptide was calculated from the concentration of produced ADP, the concentration of kinase, and the reaction time. Then the kinetic parameters were extracted from various substrate concentrations along with the corresponding velocities of three independent experiments using the Michaelis–Menten equation.

Antibodies

Anti-α-tubulin (DM1A, Sigma), anti-MBP (New England Biolabs), anti-His (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-acetyllysine (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-HEC1 (Abcam), anti-cyclinB (NewEast), and ACA (Immunovision, Springdale, AR) antibodies were obtained commercially. Western blotting signals were detected by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HeLa cells grown on coverslips were fixed by PTEM (50 mm Pipes, 0.2% Triton X-100, 10 mm EGTA, 1 mm MgCl2, pH 6.8) with 3.7% formaldehyde. After blocking with PBST containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, the fixed cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. DNA was stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides with antifade mounting medium and sealed with nail polish. Images were acquired using an Olympus ×60, numerical aperture 1.42 Plan APO N objective on a DeltaVision microscope (Applied Precision) and processed by deconvolution and z-stack projection (DeltaVision softWoRx software) as described previously (29).

Live-cell imaging

HeLa cells were cultured in glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek). Culture medium was changed to CO2-independent medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum before imaging. During imaging, the dishes were placed in a sealed chamber at 37 °C. Images of living cells were captured with the DeltaVision RT system (Applied Precision).

Transfection and siRNA/shRNA

All of the plasmids and siRNAs were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 or Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HEC1 siRNA was described previously (57), and the target sequence was 5′-AAGTTCAAAAGCTGGATGATCTT-3′. shRNA was introduced to suppress TIP60 as described previously (29), and the target sequence was 5′-CCTCCTATCCTATCGAAGCTA-3′ (sequence 1) and 5′-TCGAATTGTTTGGGCACTGAT-3′ (sequence 2).

Microtubule co-sedimentation assays

The microtubule co-sedimentation assay was described previously (48, 49, 58). Briefly, different concentrations of taxol-stabilized microtubules were incubated with HEC1N80-His or HEC1N80K53ac/K59ac-His, GST-NDC80WT, GST-NDC80K53R/K59R, GST-NDC80K53Q/K59Q for 20 min at 27 °C in BRB buffer followed by centrifugation at 80,000 rpm at 25 °C for 10 min. The pellets and supernatants were separated and solubilized in SDS sample buffer and visualized by Western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies. Densitometric quantification of co-sedimentation was carried out with ImageJ. The percentage of protein bound to microtubules was expressed as pellet signal divided by total supernatant and pellet signal. Mean binding values from three independent experiments were used to determine the apparent Kd by following the quadratic equation,

| (Eq. 1) |

where Bmax represents the maximal fractional NDC80Bonsai–tubulin complex, Kd is the dissociation constant, and X is the concentration of tubulin dimer. Given the fact that the concentrations of the NDC80 complex fragments (peptide or complex) are close to the reported Kd values (e.g. see Ref. 33), we used the full quadratic binding equation for evaluating the affinities, and Kd was calculated using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) as described previously (33). Our calculated Kd of WT Bonsai is consistent with the value in the literature (e.g. see Refs. 33 and 46).

Data analyses

To determine significant differences between means, unpaired Student's t test assuming unequal variance was performed and evaluated using GraphPad software (26). Statistical analysis was considered to be significant when the two-sided p value was <0.05.

Author contributions

G. Z., Y. C., and P. G. data curation; G. Z., Y. C., W. W., and Z. D. formal analysis; G. Z., Y. C., W. W., and Z. D. investigation; G. Z. and Y. C. writing-original draft; Y. C. and H. L. software; P. G., W. L., X. W., Z. D., L. N., H. L., and K. R. validation; P. G., W. L., and W. W. methodology; M. C., X. W., Z. D., and H. L. visualization; W. L., W. W., K. R., and X. Y. resources; W. W., Z. D., and X. Y. funding acquisition; J. H. and X. Y. project administration; M. A., Z. D., H. L., L. A., J. H., and X. Y. writing-review and editing; X. Y. supervision; X. Y. conceptualization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Hongtao Yu and Xing Liu and an anonymous reviewer for critical comments and members of our laboratories for suggestions.

This work was supported in part by National Key Research and Development Program of China Grants 2017YFA0503600 and 2016YFA0100500; Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31320103904, 31430054, 91313303, 31470792, 31621002, 31301120, 31671405, 31601097, and B1661138004; “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grants XDB19000000 and XDB08030102; 973 project Grants 2012CB917204, 2014CB964803, 2002CB713703, and 2012CB910304; Chinese Academy of Sciences Center of Excellence in Molecular and Cell Sciences Grant 2015HSC-UE010; MOE Innovative Team Grant IRT_17R102; and National Institutes of Health Grants DK56292, DK115812, and CA146133. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S8.

- CH

- calponin homology

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- CT

- C-terminal

- CBB

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

References

- 1. McKinley K. L., and Cheeseman I. M. (2016) The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 16–29 10.1038/nrm.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Black B. E., Jansen L. E., Foltz D. R., and Cleveland D. W. (2010) Centromere identity, function, and epigenetic propagation across cell divisions. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 75, 403–418 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cleveland D. W., Mao Y., and Sullivan K. F. (2003) Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112, 407–421 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00115-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCleland M. L., Kallio M. J., Barrett-Wilt G. A., Kestner C. A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Gorbsky G. J., and Stukenberg P. T. (2004) The vertebrate NDC80 complex contains SPC24 and SPC25 homologs, which are required to establish and maintain kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Curr. Biol. 14, 131–137 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCleland M. L., Gardner R. D., Kallio M. J., Daum J. R., Gorbsky G. J., Burke D. J., and Stukenberg P. T. (2003) The highly conserved NDC80 complex is required for kinetochore assembly, chromosome congression, and spindle checkpoint activity. Genes Dev. 17, 101–114 10.1101/gad.1040903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wigge P. A., and Kilmartin J. V. (2001) The NDC80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 152, 349–360 10.1083/jcb.152.2.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janke C., Ortiz J., Lechner J., Shevchenko A., Shevchenko A., Magiera M. M., Schramm C., and Schiebel E. (2001) The budding yeast proteins SPC24p and SPC25p interact with NDC80p and NUF2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 20, 777–791 10.1093/emboj/20.4.777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bharadwaj R., Qi W., and Yu H. (2004) Identification of two novel components of the human NDC80 kinetochore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13076–13085 10.1074/jbc.M310224200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ciferri C., De Luca J., Monzani S., Ferrari K. J., Ristic D., Wyman C., Stark H., Kilmartin J., Salmon E. D., and Musacchio A. (2005) Architecture of the human NDC80-HEC1 complex, a critical constituent of the outer kinetochore. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29088–29095 10.1074/jbc.M504070200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H. W., Long S., Ciferri C., Westermann S., Drubin D., Barnes G., and Nogales E. (2008) Architecture and flexibility of the yeast NDC80 kinetochore complex. J. Mol. Biol. 383, 894–903 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wei R. R., Sorger P. K., and Harrison S. C. (2005) Molecular organization of the NDC80 complex, an essential kinetochore component. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5363–5367 10.1073/pnas.0501168102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ciferri C., Musacchio A., and Petrovic A. (2007) The NDC80 complex: hub of kinetochore activity. FEBS Lett. 581, 2862–2869 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petrovic A., Pasqualato S., Dube P., Krenn V., Santaguida S., Cittaro D., Monzani S., Massimiliano L., Keller J., Tarricone A., Maiolica A., Stark H., and Musacchio A. (2010) The MIS12 complex is a protein interaction hub for outer kinetochore assembly. J. Cell Biol. 190, 835–852 10.1083/jcb.201002070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guimaraes G. J., Dong Y., McEwen B. F., and Deluca J. G. (2008) Kinetochore-microtubule attachment relies on the disordered N-terminal tail domain of HEC1. Curr. Biol. 18, 1778–1784 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller S. A., Johnson M. L., and Stukenberg P. T. (2008) Kinetochore attachments require an interaction between unstructured tails on microtubules and NDC80(HEC1). Curr. Biol. 18, 1785–1791 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheeseman I. M., Chappie J. S., Wilson-Kubalek E. M., and Desai A. (2006) The conserved KMN network constitutes the core microtubule-binding site of the kinetochore. Cell 127, 983–997 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeLuca K. F., Lens S. M., and DeLuca J. G. (2011) Temporal changes in HEC1 phosphorylation control kinetochore-microtubule attachment stability during mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 124, 622–634 10.1242/jcs.072629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emanuele M. J., Lan W., Jwa M., Miller S. A., Chan C. S., and Stukenberg P. T. (2008) Aurora B kinase and protein phosphatase 1 have opposing roles in modulating kinetochore assembly. J. Cell Biol. 181, 241–254 10.1083/jcb.200710019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Long A. F., Udy D. B., and Dumont S. (2017) HEC1 tail phosphorylation differentially regulates mammalian kinetochore coupling to polymerizing and depolymerizing microtubules. Curr. Biol. 27, 1692–1699.e3 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Umbreit N. T., Gestaut D. R., Tien J. F., Vollmar B. S., Gonen T., Asbury C. L., and Davis T. N. (2012) The NDC80 kinetochore complex directly modulates microtubule dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16113–16118 10.1073/pnas.1209615109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang G., Kelstrup C. D., Hu X. W., Kaas Hansen M. J., Singleton M. R., Olsen J. V., and Nilsson J. (2012) The NDC80 internal loop is required for recruitment of the Ska complex to establish end-on microtubule attachment to kinetochores. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3243–3253 10.1242/jcs.104208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maure J. F., Komoto S., Oku Y., Mino A., Pasqualato S., Natsume K., Clayton L., Musacchio A., and Tanaka T. U. (2011) The NDC80 loop region facilitates formation of kinetochore attachment to the dynamic microtubule plus end. Curr. Biol. 21, 207–213 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Helgeson L. A., Zelter A., Riffle M., MacCoss M. J., Asbury C. L., and Davis T. N. (2018) Human Ska complex and NDC80 complex interact to form a load-bearing assembly that strengthens kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2740–2745 10.1073/pnas.1718553115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng Z., Ke Y., Ding X., Wang F., Wang H., Wang W., Ahmed K., Liu Z., Xu Y., Aikhionbare F., Yan H., Liu J., Xue Y., Yu J., Powell M., et al. (2008) Functional characterization of TIP60 sumoylation in UV-irradiated DNA damage response. Oncogene 27, 931–941 10.1038/sj.onc.1210710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu Q., Hu H., Lan J., Emenari C., Wang Z., Chang K. S., Huang H., and Yao X. (2009) PML3 orchestrates the nuclear dynamics and function of TIP60. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8747–8759 10.1074/jbc.M807590200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Murr R., Loizou J. I., Yang Y. G., Cuenin C., Li H., Wang Z. Q., and Herceg Z. (2006) Histone acetylation by Trrap-Tip60 modulates loading of repair proteins and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 91–99 10.1038/ncb1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun Y., Jiang X., Chen S., Fernandes N., and Price B. D. (2005) A role for the Tip60 histone acetyltransferase in the acetylation and activation of ATM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13182–13187 10.1073/pnas.0504211102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun Y., Jiang X., Xu Y., Ayrapetov M. K., Moreau L. A., Whetstine J. R., and Price B. D. (2009) Histone H3 methylation links DNA damage detection to activation of the tumour suppressor Tip60. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1376–1382 10.1038/ncb1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mo F., Zhuang X., Liu X., Yao P. Y., Qin B., Su Z., Zang J., Wang Z., Zhang J., Dou Z., Tian C., Teng M., Niu L., Hill D. L., Fang G., et al. (2016) Acetylation of Aurora B by TIP60 ensures accurate chromosomal segregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 226–232 10.1038/nchembio.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bao X., Liu H., Liu X., Ruan K., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Hu Q., Liu Y., Akram S., Zhang J., Gong Q., Wang W., Yuan X., Li J., Zhao L., et al. (2018) Mitosis-specific acetylation tunes Ran effector binding for chromosome segregation. J Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 18–32 10.1093/jmcb/mjx045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang Y., and Yu H. (2018) Partner switching for Ran during the mitosis dance. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 89–90 10.1093/jmcb/mjx048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng L., Chen Y., and Lee W. H. (1999) HEC1p, an evolutionarily conserved coiled-coil protein, modulates chromosome segregation through interaction with SMC proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5417–5428 10.1128/MCB.19.8.5417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ciferri C., Pasqualato S., Screpanti E., Varetti G., Santaguida S., Dos Reis G., Maiolica A., Polka J., De Luca J. G., De Wulf P., Salek M., Rappsilber J., Moores C. A., Salmon E. D., and Musacchio A. (2008) Implications for kinetochore-microtubule attachment from the structure of an engineered NDC80 complex. Cell 133, 427–439 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei R. R., Al-Bassam J., and Harrison S. C. (2007) The NDC80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 54–59 10.1038/nsmb1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu T., Dou Z., Qin B., Jin C., Wang X., Xu L., Wang Z., Zhu L., Liu F., Gao X., Ke Y., Wang Z., Aikhionbare F., Fu C., Ding X., and Yao X. (2013) Phosphorylation of microtubule-binding protein HEC1 by mitotic kinase Aurora B specifies spindle checkpoint kinase Mps1 signaling at the kinetochore. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36149–36159 10.1074/jbc.M113.507970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao S., Xu W., Jiang W., Yu W., Lin Y., Zhang T., Yao J., Zhou L., Zeng Y., Li H., Li Y., Shi J., An W., Hancock S. M., He F., et al. (2010) Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science 327, 1000–1004 10.1126/science.1179689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dou Z., Liu X., Wang W., Zhu T., Wang X., Xu L., Abrieu A., Fu C., Hill D. L., and Yao X. (2015) Dynamic localization of Mps1 kinase to kinetochores is essential for accurate spindle microtubule attachment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4546–E4555 10.1073/pnas.1508791112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeLuca J. G., Gall W. E., Ciferri C., Cimini D., Musacchio A., and Salmon E. D. (2006) Kinetochore microtubule dynamics and attachment stability are regulated by HEC1. Cell 127, 969–982 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zaytsev A. V., Mick J. E., Maslennikov E., Nikashin B., DeLuca J. G., and Grishchuk E. L. (2015) Multisite phosphorylation of the NDC80 complex gradually tunes its microtubule-binding affinity. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 1829–1844 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rack J. G., Morra R., Barkauskaite E., Kraehenbuehl R., Ariza A., Qu Y., Ortmayer M., Leidecker O., Cameron D. R., Matic I., Peleg A. Y., Leys D., Traven A., and Ahel I. (2015) Identification of a class of protein ADP-ribosylating sirtuins in microbial pathogens. Mol. Cell 59, 309–320 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patel H., Stavrou I., Shrestha R. L., Draviam V., Frame M. C., and Brunton V. G. (2016) Kindlin1 regulates microtubule function to ensure normal mitosis. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 338–348 10.1093/jmcb/mjw009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neumann H., Peak-Chew S. Y., and Chin J. W. (2008) Genetically encoding Nϵ-acetyllysine in recombinant proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 232–234 10.1038/nchembio.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Neumann H., Hancock S. M., Buning R., Routh A., Chapman L., Somers J., Owen-Hughes T., van Noort J., Rhodes D., and Chin J. W. (2009) A method for genetically installing site-specific acetylation in recombinant histones defines the effects of H3 K56 acetylation. Mol. Cell 36, 153–163 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dalziel K. (1962) Physical significance of Michaelis constants. Nature 196, 1203–1205 10.1038/1961203b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bar-Even A., Noor E., Savir Y., Liebermeister W., Davidi D., Tawfik D. S., and Milo R. (2011) The moderately efficient enzyme: evolutionary and physicochemical trends shaping enzyme parameters. Biochemistry 50, 4402–4410 10.1021/bi2002289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ji Z., Gao H., and Yu H. (2015) CELL DIVISION CYCLE. Kinetochore attachment sensed by competitive Mps1 and microtubule binding to NDC80C. Science 348, 1260–1264 10.1126/science.aaa4029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hiruma Y., Sacristan C., Pachis S. T., Adamopoulos A., Kuijt T., Ubbink M., von Castelmur E., Perrakis A., and Kops G. J. (2015) CELL DIVISION CYCLE. Competition between MPS1 and microtubules at kinetochores regulates spindle checkpoint signaling. Science 348, 1264–1267 10.1126/science.aaa4055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hua S., Wang Z., Jiang K., Huang Y., Ward T., Zhao L., Dou Z., and Yao X. (2011) CENP-U cooperates with HEC1 to orchestrate kinetochore-microtubule attachment. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1627–1638 10.1074/jbc.M110.174946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Du J., Cai X., Yao J., Ding X., Wu Q., Pei S., Jiang K., Zhang Y., Wang W., Shi Y., Lai Y., Shen J., Teng M., Huang H., Fei Q., et al. (2008) The mitotic checkpoint kinase NEK2A regulates kinetochore microtubule attachment stability. Oncogene 27, 4107–4114 10.1038/onc.2008.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou R., Cao X., Watson C., Miao Y., Guo Z., Forte J. G., and Yao X. (2003) Characterization of protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of ezrin in gastric parietal cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35651–35659 10.1074/jbc.M303416200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xia P., Wang Z., Liu X., Wu B., Wang J., Ward T., Zhang L., Ding X., Gibbons G., Shi Y., and Yao X. (2012) EB1 acetylation by P300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) ensures accurate kinetochore-microtubule interactions in mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16564–16569 10.1073/pnas.1202639109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kinoshita E., Kinoshita-Kikuta E., and Koike T. (2009) Separation and detection of large phosphoproteins using Phos-tag SDS-PAGE. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1513–1521 10.1038/nprot.2009.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fang C., Guo X., Lv X., Yin R., Lv X., Wang F., Zhao J., Bai Q., Yao X., and Chen Y. (2017) Dysbindin promotes progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via direct activation of PI3K. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 504–515 10.1093/jmcb/mjx043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yan M., Chu L., Qin B., Wang Z., Liu X., Jin C., Zhang G., Gomez M., Hergovich A., Chen Z., He P., Gao X., and Yao X. (2015) Regulation of NDR1 activity by PLK1 ensures proper spindle orientation in mitosis. Sci. Rep. 5, 10449 10.1038/srep10449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jiang H., Wang W., Zhang Y., Yao W. W., Jiang J., Qin B., Yao W. Y., Liu F., Wu H., Ward T. L., Chen C. W., Liu L., Ding X., Liu X., and Yao X. (2015) Cell polarity kinase MST4 cooperates with cAMP-dependent kinase to orchestrate histamine-stimulated acid secretion in gastric parietal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28272–28285 10.1074/jbc.M115.668855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu T., Zuo Y., Cai R., Huang X., Wu S., Zhang C., Chin Y. E., Li D., Zhang Z., Xia N., Wang Q., Shen H., Yao X., Zhang Z. Y., Xue S., et al. (2017) SENP1 regulates IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling through STAT3-SOCS3 negative feedback loop. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu D., Liu X., Zhou T., Yao W., Zhao J., Zheng Z., Jiang W., Wang F., Aikhionbare F. O., Hill D. L., Emmett N., Guo Z., Wang D., Yao X., and Chen Y. (2016) IRE1-RACK1 axis orchestrates ER stress preconditioning-elicited cytoprotection from ischemia/reperfusion injury in liver. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 144–156 10.1093/jmcb/mjv066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Akram S., Yang F., Li J., Adams G., Liu Y., Zhuang X., Chu L., Liu X., Emmett N., Thompson W., Mullen M., Muthusamy S., Wang W., Mo F., and Liu X. (2018) LRIF1 interacts with HP1α to coordinate accurate chromosome segregation during mitosis. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10.1093/jmcb/mjy040 10.1093/jmcb/mjy040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.