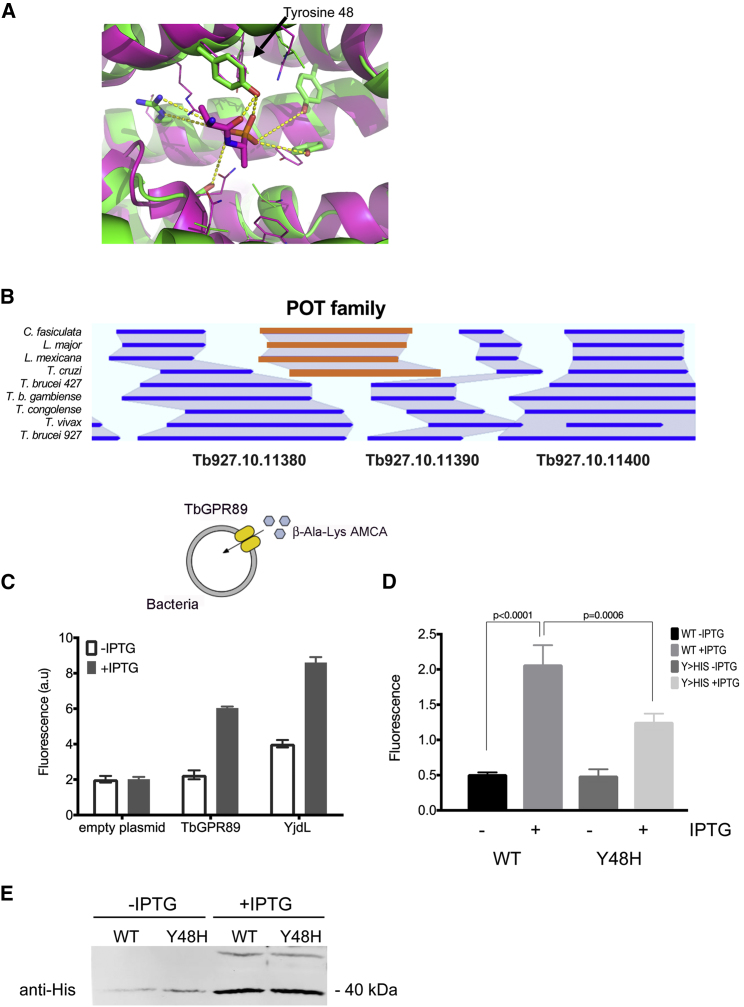

Figure 3.

TbGPR89 Transports Oligopeptides

(A) Homology modeling of TbGPR89 and the G. kaustophilus POT protein. Superimposition of the TbGPR89 model (green) onto the G. kaustophilus template (purple), centered on the dipeptide analog alafosfalin binding pocket (residues of which are shown as lines). Side chains of TbGPR89 residues within interaction distance of the ligand are shown as thicker lines. Potential H-bonds between the model and the ligand are highlighted by dashed yellow lines. The predicted substrate interacting tyrosine 48 in TbGPR89 is annotated.

(B) Representation of the syntenic regions of the genomes of respective kinetoplastid organisms, with the location of a conventional POT family member highlighted in orange. This is missing in African trypanosomes.

(C) Relative uptake of fluorescent dipeptide β-ALA-Lys-AMCA in E. coli induced (+IPTG) or not induced (−IPTG) to express TbGPR89, E. coli YjdL, or an empty plasmid control. Fluorescence is in arbitrary units. n = 3; error bars, SEM.

(D) Mutation of the predicted dipeptide interacting residue tyrosine 48 to histidine 48 in TbGPR89 reduces transport of the fluorescent dipeptide β-Ala-Lys-AMCA when expressed in E. coli. Fluorescence is in arbitrary units. n = 3; error bars, SEM.

(E) Wild-type and Y48H mutant TbGPR89 are expressed at equivalent levels in induced (+IPTG) and uninduced (−IPTG) E. coli.

See also Figure S4.