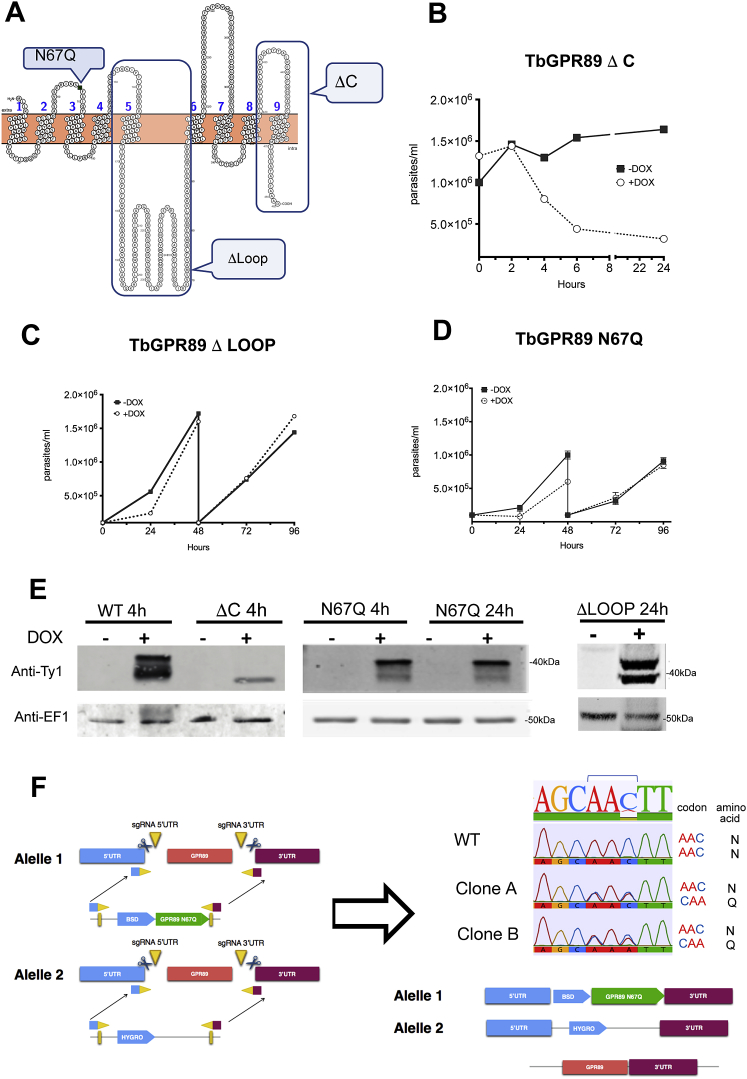

Figure S3.

GPR89 Mutants Do Not Drive Stumpy Formation, Related to Figure 2

(A) Schematic representation of different domains mutated within TbGPR89.

(B–D) Growth of pleomorphic parasites induced or not to express TbGPR89 with a C-terminal truncation (TbGPR89 ΔC, B), a deleted loop region (TbGPR89 Δ loop; C), or a mutated predicted N-glycosylation site (TbGPR89 N67Q ; D). In C and D, cultures were diluted at 48h to keep cell numbers below 2x106/ml. Error bars = SEM.

(E) protein expression of TbGPR89 mutants in the respective cells lines in panels B-D at 4h post induction and, for the N glycosylation site, at 4h and 24h. In each case, the loading control is EF1α. The detected protein in the TbGPR89 ΔC samples is reduced because of the presence of fewer viable cells after induction of the ectopic protein expression.

(F) Allelic replacement of wild-type TbGPR89 with TbGPR89 N67Q by CRISPR. One TbGPR9 allele was replaced with the TbGPR89 N67Q mutant (linked to a blasticidin resistance gene) and the other with a hygromycin resistance gene. Analysis of two resulting clones (Clone A, Clone B) showed retention of a wild-type TbGPR89 gene copy, validated by PCR (not shown) and sequence analysis, where both the mutant and wild-type sequence are detected. PCR using primers targeting flanking sequences demonstrated that the mutant allele and hygromycin resistance cassette integrated at the expected genomic location; the additional wild-type allele genomic location has not been mapped, but retains the endogenous 3′UTR (not shown).