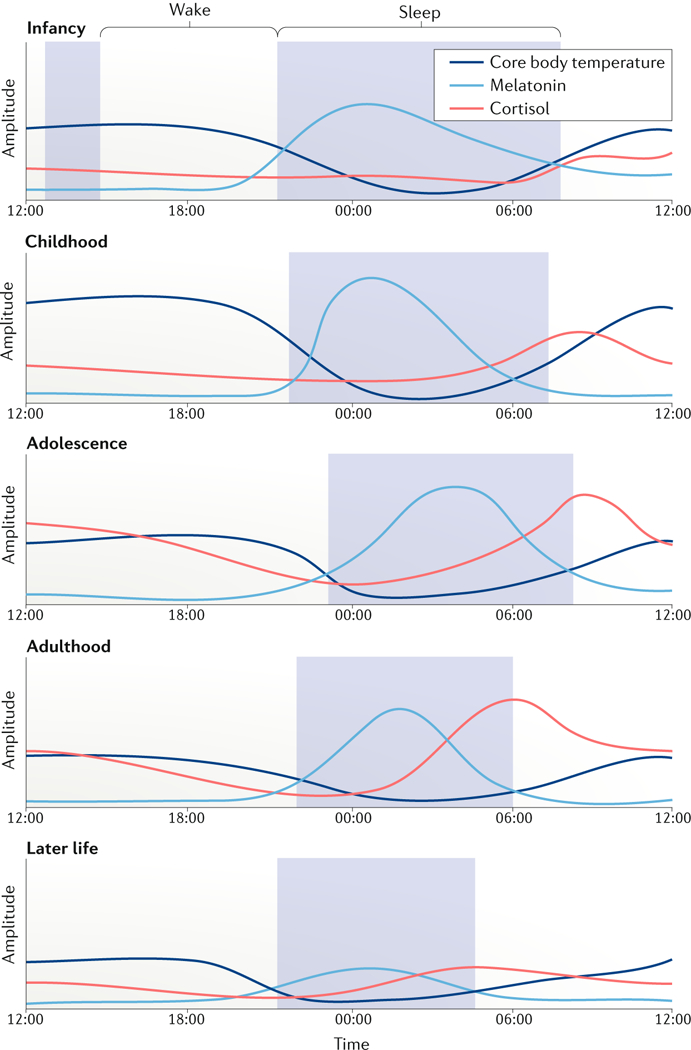

Fig. 2 |. rhythms across the lifespan.

Schematic of circadian rhythm changes from infancy, adolescence, adulthood and older age. During infancy, sleep–wake rhythms are ultradian and consolidate during the first year of development. From childhood to adolescence, there is a marked shift from an early to a late chronotype, which subsequently becomes earlier during adulthood, with shorter sleep durations through adulthood. Rhythms undergo a gradual loss of amplitude with ageing. Temperature rhythms peak during childhood, and amplitudes steadily reduce during ageing. Melatonin rhythms are delayed during adolescence, with overall levels peaking during childhood and considerably decreasing during ageing. Similarly, rodent studies have demonstrated that suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) activity rhythms gradually decline with ageing (not shown). Cortisol rhythms peak earlier in the morning during childhood and, with age, gradually widen and reduce in overall amplitude. The amplitude of rhythmic gene expression in the brain and other tissues is reduced during ageing, affecting tissue homeostasis and function (not shown).