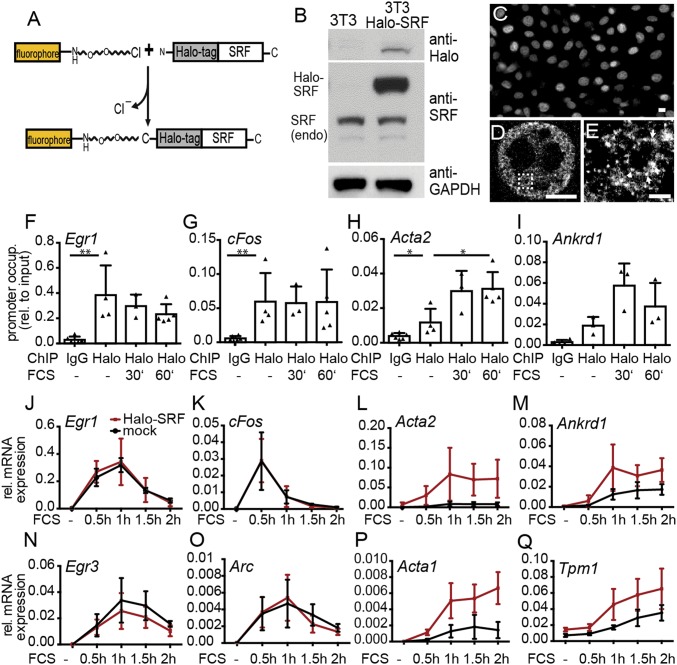

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Halo-SRF localization and function. (A) Scheme of SRF fused to the HaloTag at the N terminus. The HaloTag is an enzyme reacting with fluorophores such as TMR or SiR if modified by a chloroalkane linker. (B) Characterization of Halo-SRF overexpression in stably transfected NIH 3T3 cells (NIH 3T3 Halo-SRF) using immunoblotting. Halo-SRF was recognized by anti-Halo and anti-SRF directed antibodies. Endogenous SRF (endo) was detected with anti-SRF antibodies. (C) NIH 3T3 Halo-SRF cells stained with TMR revealed constitutive nuclear localization of Halo-SRF in conventional fluorescence microscopy. (D) The dSTORM microscopy of Halo-SRF molecules labeled with anti-Halo directed antibodies show individual SRF clusters distributed throughout the entire nucleoplasm. (E) A close-up view of the boxed area in D reveals Halo-SRF localization in clusters (arrows). (Scale bars: C, 10 μm; D, 5 μm; E, 1 μm.) (F–I) ChIP demonstrating occupancy of Halo-SRF at several SRF target genes. FCS stimulation did not alter Halo-SRF occupancy at IEG promoters of (F) Egr1 or (G) cFos but enhanced occupancy at cytoskeletal promoters such as (H) Acta2 and (I) Ankrd1. Each triangle represents an independent culture. Data are depicted as mean ± SD (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; Mann−Whitney u test). (J, K, N, and O) Halo-SRF overexpression did not alter gene expression profiles of IEGs in comparison with mock NIH 3T3 cells expressing endogenous SRF only. (L, M, P, and Q) Halo-SRF enhanced mRNA abundance of cytoskeletal genes in relation to mock transfected cells. Values are calculated from at least three independent cultures. Data are depicted as mean ± SD.