Abstract

Background

Scutellarin is a natural flavone compound that possesses anti-tumor and chemosensitization effects in several cancers. However, the effects of scutellarin on metastasis and chemoresistance in glioma have not been illustrated.

Methods

Glioma cells were treated with scutellarin in the presence or absence of LY294002. Cell proliferation was measured using a Cell Proliferation BrdU ELISA kit. Cell migration and invasion were analyzed using transwell assay. The expressions of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, p-PI3K, PI3K, p-AKT, AKT, p-mTOR and mTOR were measured using Western blot. Furthermore, cells were incubated in the presence of cisplatin with or without the pretreatment of scutellarin. Cell viability was detected by the MTT assay. Cell apoptosis was measured using a histone/DNA ELISA detection kit. The expressions of ABCB1 and ABCG2 were detected using Western blot.

Results

In the present study, we found that scutellarin inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion of glioma cells. Scutellarin induced E-cadherin expression and reduced the expressions of N-cadherin, and vimentin in glioma cells. Our results also revealed that scutellarin enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin, as evidenced by the decreased cell viability to cisplatin and induced cell apoptosis. Moreover, scutellarin inhibited the expressions of ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 and ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2 in cisplatin-resistant glioma cells. Scutellarin also prevented the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway.

Conclusion

The data suggested that scutellarin suppressed metastasis and chemoresistance in glioma cells. Scutellarin might be a new therapeutic approach for the glioma therapy.

Keywords: glioma, scutellarin, metastasis, chemoresistance, PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway

Introduction

Glioma is a type of tumor occurring in the glial cells and represents the majority of malignancies of the central nervous system (CNS).1 It has been one of the most aggressive tumors in terms of high morbidity and mortality.1 Glioma can cause plenty of symptoms, such as headache, vomiting, seizures, visual loss, weakness, or numbness, which depend on the affected part of the CNS.2,3 The treatment of glioma remains a challenging task because of the special pathological and physiological characteristics.

High-grade glioma has a tendency to infiltrate and can lead to the breakdown of blood–brain barrier as the tumor grows.3,4 Consequently, it is hard to completely cure the glioma through clinical surgery.3 Recent evidence has documented a utility for adjuvant chemotherapy with procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine or temozolomide in the management of gliomas.5 A combined approach using surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy is utilized according to the location and grade of the tumor.6,7 Although these therapeutic strategies can extend patient’s postoperative survival, most cases eventually demonstrate resistance to drugs.8 Therefore, the prognosis of high-grade glioma is generally poor.4 Glioma recurrence is always observed even after complete surgical excision or radio- and chemotherapy.8 To meet this challenge, many researchers have focused on exploring agents attenuating the metastasis and chemoresistance.9,10

Scutellarin is a natural flavone compound that can be found in Scutellaria barbata and Scutellaria lateriflora.11 Scutellarin has been demonstrated to possess various beneficial biological roles, including anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor activities.11 Previous studies indicate that scutellarin inhibits metastasis of various tumors, such as tongue squamous carcinoma,12 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),13 and colorectal cancer.14 In addition, it has been reported that scutellarin retains chemosensitization effect, as evidenced by the reduction of chemoresistance in several cancer cells.15,16 Nevertheless, the roles of scutellarin in glioma have not yet been clarified. The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential effects of scutellarin in governing cisplatin resistance and metastasis in glioma cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human glioma cell lines, U87 and U251, were obtained from Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). The cells were grown in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.1% of penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of scutellarin (50 and 100 µM) for 48 hours.

Cell proliferation assay

The U87 and U251 cells (2×103 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight. Then, the cells were treated with scutellarin (50 and 100 µM) for 48 hours. Cell proliferation of U87 and U251 cells was measured using a Cell Proliferation BrdU ELISA kit (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Burgess Hill, West Sussex, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Ultimately, the absorbance was recorded at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell migration and invasion assays

Cell migration and invasion were analyzed using transwell assay. For the invasion assay, the inserts were coated with matrigel (1 mg/mL; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells (1×105 cells per well) were seeded in the upper chamber with serum-free medium. Medium containing 10% FBS was used as a chemoattractant and was added to the lower chamber. After 24 hours, the filters were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Then the number of the cells in five random fields was counted. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Western blot

Cells were harvested and the cell lysates were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After determination of protein concentration with a BCA assay kit, equal amount of protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Then the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. Then the membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibodies against the following proteins: E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, cleaved caspase-3, p53, Bax, Bcl-2, LC3I, LC3II, p-ERK, ERK, Akt, and p-Akt (diluted in 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA); ABCB1, ABCG2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), p-PI3K, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), p-mTOR, and GAPDH (diluted in 1:800; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Then, the membranes were probed with secondary antibody (diluted in 1:3,000; Abcam) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The bands were visualized with a Plus-ECL kit (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Establishment of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells

To establish the cisplatin-resistant cells, the U87 and U251 cells were exposed to the medium with increasing concentrations of cisplatin (1, 10, 50, and 100 µM; Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Cisplatin-containing culture medium was changed every 4 hours. After continuous exposure to cisplatin for 2 days, the medium was changed to a fresh cisplatin-free medium until the cells recovered favorably. After that, the cisplatin-resistant cells were maintained in medium containing 100 µM cisplatin to maintain drug resistance. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

MTT assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 1×104 per well and incubated for 24 hours in the presence of cisplatin (2, 4, 8, and 16 µM) with or without the pretreatment of scutellarin (50 and 100 µM). Then MTT solution (20 µL, 5 mg/mL) was added and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. The formazan product was dissolved by adding DMSO (100 µL). The absorbance was measured at 540 nm wavelength using a plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Histone/DNA ELISA for detecting apoptosis

The cell apoptosis was measured using a histone/DNA ELISA detection kit (Roche Diagnostics Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells with different treatments were harvested and treated with lysis buffer. After centrifugation at 200 g for 10 minutes, the supernatant was transferred to 96-well plates precoated with streptavidin. Then a mixture of biotinylated anti-histone and peroxidase-tagged anti-DNA antibody was added to the cell lysate and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, the 2,2-azinobis-3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid substrate was added to the plates and incubated for 20 minutes. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 405 nm using a plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

RNA interference and transfection

The small interfering RNA targeting ABCB1 (si-ABCB1) and its negative control (si-control) were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). For in vitro transfection, U87/DDP and U251/DDP cells were transfected with si-ABCB1 or si-control using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are graphically represented as mean ± SD. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 statistical software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Analysis among groups was conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Analysis between two groups was carried out using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Significant differences were defined as P<0.05.

Results

Scutellarin suppressed the proliferation of glioma cells

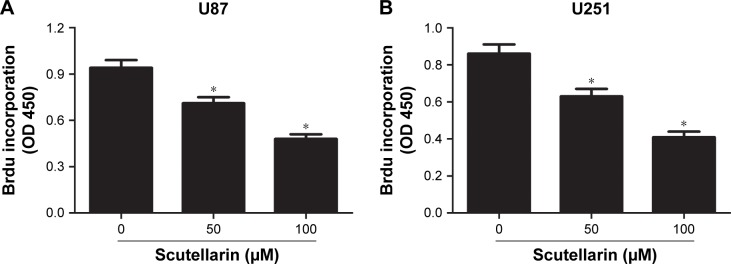

First, we evaluated the effect of scutellarin on cell proliferation of U87 and U251 cells. After 48 hours of treatment with scutellarin, the cell proliferation of U87 cells was significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner compared with the untreated cells (Figure 1A). Scutellarin treatment also inhibited the cell proliferation of U251 cells at the same time (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Scutellarin suppressed the proliferation of glioma cells.

Notes: Cell proliferation of U87 (A) and U251 cells (B) after 48 hours treatment with scutellarin or vehicle. *P<0.05 vs control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Scutellarin decreased the migration and invasion of glioma cells

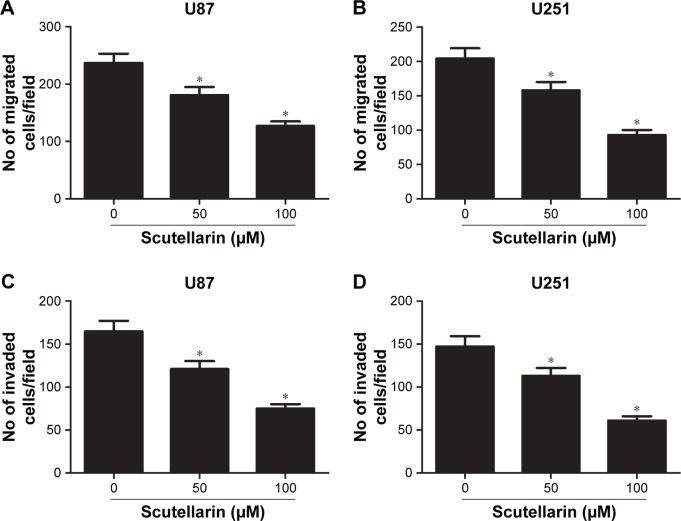

Next, we investigated the effect of scutellarin on migration and invasion of U87 and U251 cells. As shown in Figure 2A and B, the transwell assay showed that the migrated U87 and U251 cells were much fewer in the scutellarin-treated groups than in the untreated group. The numbers of the invaded cells were significantly reduced after scutellarin treatment (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Scutellarin reduced the migration and invasion of glioma cells.

Notes: (A–B) Cell migration of U87 and U251 cells was measured using transwell assay. (C–D) Cell invasion of U87 and U251 cells was measured using matrigel-coated transwell inserts. *P<0.05 vs control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

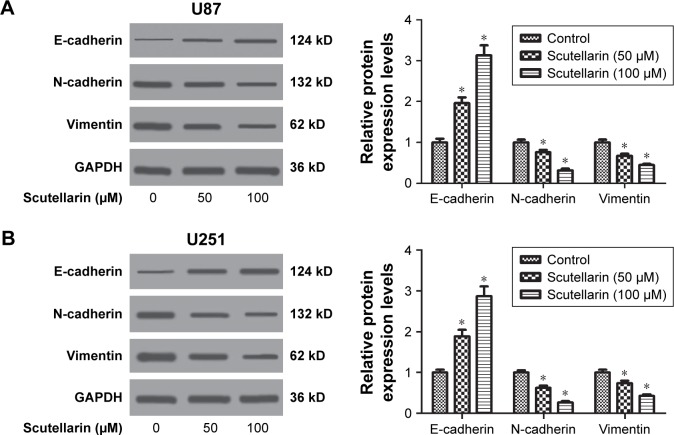

Scutellarin reversed the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype in glioma cells

The EMT phenotype was analyzed by detecting the expressions of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin. Western blot analysis indicated that scutellarin caused increase in E-cadherin expression and resulted in decreases in expressions of N-cadherin, and vimentin in both U87 and U251 cells (Figure 3A and B). The results indicated that scutellarin reversed the EMT phenotype in U87 and U251 cells.

Figure 3.

Scutellarin reversed the epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype in glioma cells.

Notes: After treatment with or without scutellarin for 48 hours, Western blot analysis was performed to detect the expressions of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin in U87 (A) and U251 cells (B). *P<0.05 vs control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Scutellarin enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin in glioma cells

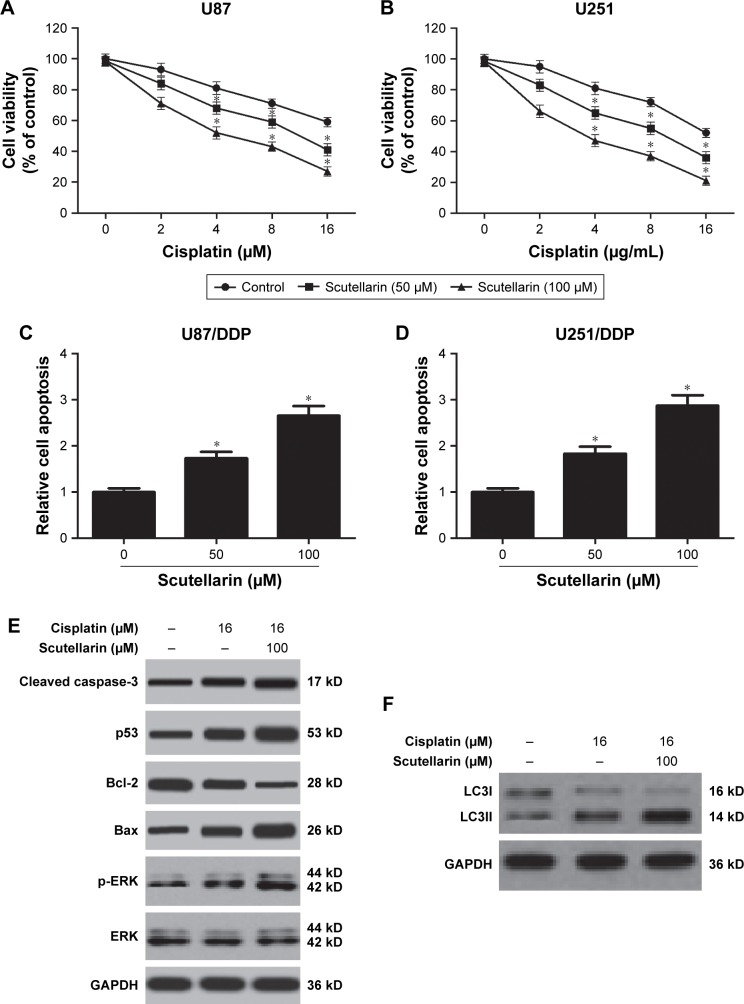

To explore the effect of scutellarin on cisplatin sensitivity, the cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells were established. The cell viability of cisplatin-resistant U87 cells was markedly decreased with the scutellarin pretreatment (Figure 4A). Simultaneously, scutellarin pretreatment reduced the IC50 value of cisplatin-resistant U251 cells (Figure 4B). We also examined synergistic effects of cisplatin with scutellarin. Combined cisplatin and 100 µM scutellarin showed obvious synergism (Figure S1C and D), whereas the cytotoxic effect of scutellarin on cisplatin-resistant U87/DDP cells, U251/DDP cells, and astrocytes was dismal (Figure S1A, B, and E). Furthermore, we evaluated the cell apoptosis of the cisplatin-resistant cells. Figure 4C and D showed that scutellarin promoted the cell apoptosis of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells. In addition, we observed that scutellarin-enhanced cisplatin induced the levels of cleaved caspase-3, p53, Bax, and p-ERK, as well as increased LC3II-to-LC3I ratio in U87 cells (Figure 4E and F).

Figure 4.

Scutellarin-enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin in glioma cells.

Notes: The cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells were established. (A, B) Cell viability of cisplatin-resistant U87 and cisplatin-resistant U251 cells to cisplatin after scutellarin pretreatment or vehicle treatment. (C, D) Cell apoptosis of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells after scutellarin pretreatment or vehicle treatment. (E) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3, p53, Bax, Bcl-2, p-ERK, and ERK levels in U87/DDP cells treated by cisplatin, or scutellarin, or the combination. (F) Western blot analysis of LC3I and LC3II levels in U87/DDP cells treated by cisplatin, or scutellarin, or the combination. *P<0.05 vs control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

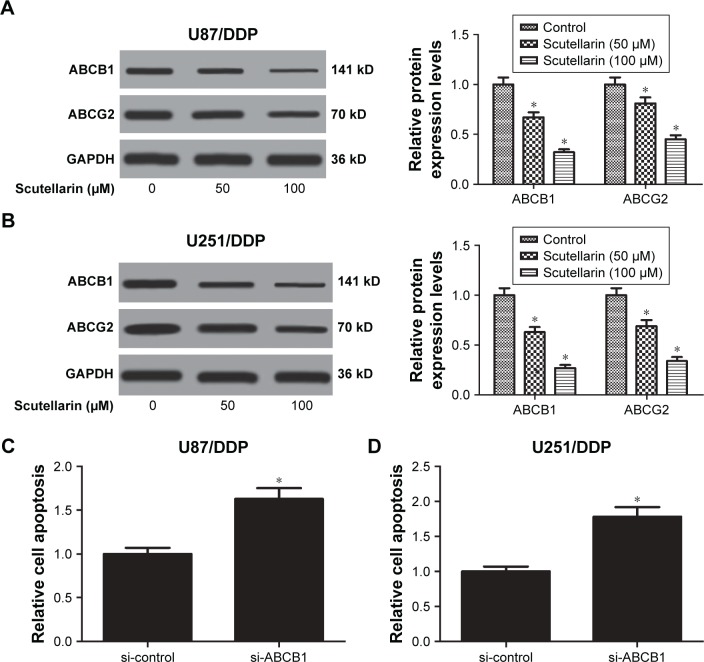

Scutellarin prevented the expression of multidrug-resistant proteins in glioma cells

Moreover, we analyzed the expressions of multidrug-resistant proteins including ABCB1 and ABCG2. After scutellarin pretreatment, the expressions of ABCB1 and ABCG2 were significantly decreased in both cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells (Figure 5A and B). The results indicated that scutellarin reduced the expressions of multidrug-resistant proteins in cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells, which may contribute to the effect of scutellarin on cisplatin sensitivity. Furthermore, knockdown of ABCB1 significantly induced cell apoptosis in U87/DDP cells and U251/DDP cells (Figure 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Scutellarin suppressed the expressions of multidrug-resistant proteins in glioma cells.

Notes: The expressions of multidrug-resistant proteins including ABCB1 and ABCG2 in cisplatin-resistant U87 (A) and U251 cells (B) were analyzed by Western blot. *P<0.05 vs control. (C) U87/DDP cells were transfected with si-control or si-ABCB1 for 24 hours, and cell apoptosis was detected. (D) U251/DDP cells were transfected with si-control or si-ABCB1 for 24 hours, and cell apoptosis was detected. *P<0.05 vs si-control. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

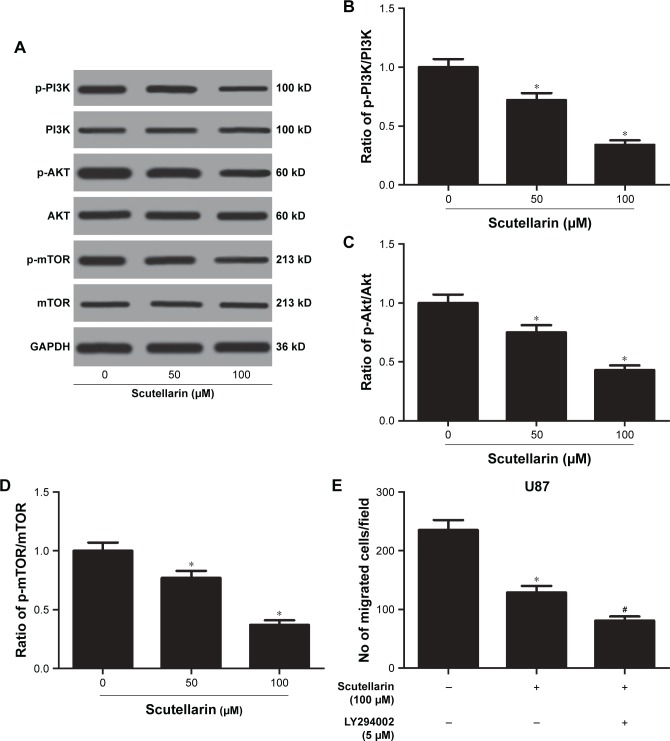

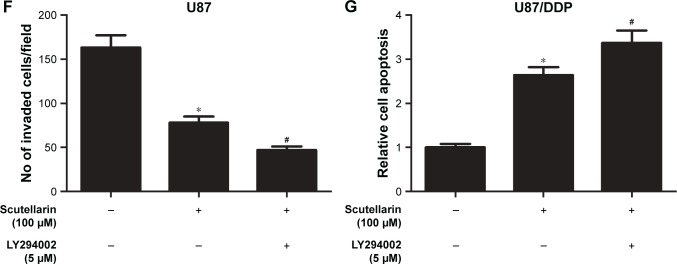

Scutellarin prevented the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in glioma cells

We next evaluated the mechanism by which scutellarin regulates the U87 cells. Figure 6A–D showed that the protein levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR were markedly reduced by scutellarin treatment in U87 cells. Furthermore, scutellarin treatment also caused inhibitory effect on the expressions of p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR in cisplatin-resistant U87 cells. Moreover, we observed that the inhibitor of PI3K/Akt pathway, LY294002 could enhance the effects of scutellarin on cell migration, invasion, and cisplatin-induced cell death in U87 cells (Figure 6E–G). These results suggested that scutellarin suppressed the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in glioma cells, which might contribute to the effects of scutellarin on glioma cells.

Figure 6.

Scutellarin prevented the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in glioma cells.

Notes: The protein levels of p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-mTOR were analyzed by Western blot. (A) Representative image of Western blot. (B–D) Quantification analysis of p-PI3K/PI3K, p-Akt/Akt and p-mTOR/mTOR. U87 cells were treated by scutellarin with or without LY294002 for 24 hours. (E) Cell migration was measured using transwell assay. (F) Cell invasion was measured using matrigel-coated transwell inserts. (G) Cell apoptosis was measured using a histone/DNA ELISA detection kit. *P<0.05 vs control. #P<0.05 vs scutellarin group. Data are represented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Scutellarin is a natural compound that acts as tumor suppressor in many kinds of tumors such as prostate, breast, and colorectal cancers.11 Scutellarin has been demonstrated to inhibit tumor growth through suppressing cell proliferation and inducing cell apoptosis of cancer cells.17,18 In the present study, we investigated the effect of scutellarin on cell proliferation of two human glioma cell lines, U87 and U251 cells. Our data showed that scutellarin inhibited the cell proliferation of U87 and U251 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Increased cell migration and invasion abilities are principal characteristics of metastatic phenotype and are necessary for the initiation of metastatic cascade.19 As was seen in a previous paper by Ke et al, scutellarin mediates the inhibition of cell migration and invasion abilities of HCC cells.13 Scutellarin also inhibits the lung and intrahepatic metastasis of HCC cells in vivo.13 Besides, scutellarin inhibits the invasion and migration of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells.14 Next, we evaluated the effect of scutellarin on invasion and migration of U87 and U251 cells. As expected, scutellarin significantly mitigated the invasion and migration abilities of U87 and U251 cells. EMT is an essential process that occurs in numerous events including wound healing, tissues fibrosis, and the initiation of metastasis during cancer progression.20,21 Loss of E-cadherin and increased levels of N-cadherin, fibronetin, and vimentin are considered to be fundamental events in EMT phenotype.21 We found that scutellarin caused increase in E-cadherin expression and resulted in decreases in expressions of N-cadherin, and vimentin in both U87 and U251 cells, indicating that scutellarin reversed the EMT phenotype. Collectively, we concluded that scutellarin significantly attenuated the metastasis of the glioma cells.

Since it is difficult to conduct the surgical resection of glioma, radio- and chemotherapy play principal roles in the clinical therapy for glioma.6,7 However, radio- and chemotherapy have failed to improve prognosis of glioma due to chemoresistance. Therefore, there is a need to explore a novel therapeutic agent to overcome chemoresistance in glioma therapy. Scutellarin was reported to sensitize PC3 prostate cancer cells to cisplastin treatment in a dose-dependent manner.16 Sun et al15 demonstrated that scutellarin enhanced the cisplatin sensitivity of the cisplatin-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer cells A549/DDP by inducing apoptosis and autophagy. In our work, we revealed that the cell viability of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells to cisplatin was markedly decreased in the scutellarin-treated cells. Scutellarin also induced cell apoptosis of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells, which suggested that scutellarin enhanced the sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant U87 and U251 cells to cisplatin. ABCB1 and ABCG2 have critical roles in conferring multidrug resistance in tumor cells.22 Herein, we showed that scutellarin prevented the expression of ABCB1 and ABCG2 in glioma cells.

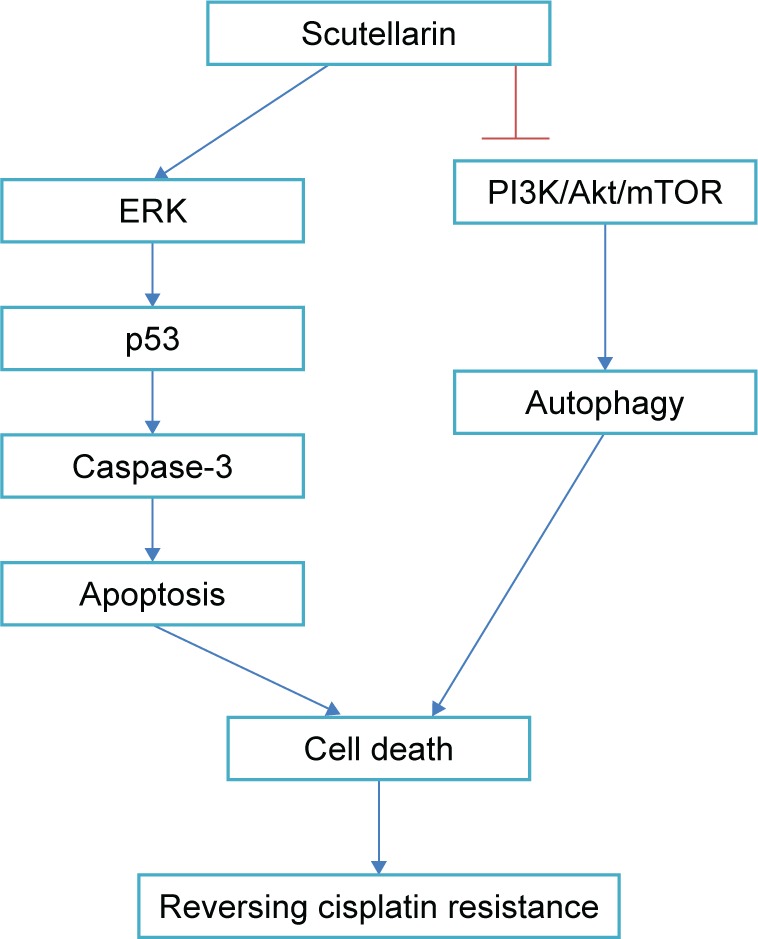

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is an important intracellular signaling pathway in regulating various cellular processes, such as cell survival, growth, differentiation, proliferation, cycle, apoptosis, and metabolism.23 It has been proved to be overactive in many kinds of cancers and acts as a key oncogenic signaling pathway, which is linked to malignant transformation, tumorigenesis, metastasis and resistance in anticancer therapies.23–26 Given the significance of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in cancer development and treatment, it can be inferred that inhibitors of this pathway may have great potential to deliver clinical benefit.25 In fact, numerous agents that targeted the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway are under investigation for the treatment of many cancers including glioma.26,27 In the present study, we aimed to investigate whether scutellarin could affect the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. The results showed that scutellarin inhibited the activation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in glioma cells, indicating that inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway might in part contribute to the effects of scutellarin (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Scutellarin reverses cisplatin resistance in glioma cells through regulating the ERK/p53/caspase-3 and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways.

Conclusion

In summary, we validated that scutellarin inhibited cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT phenotype in glioma cells. Moreover, our results also revealed that scutellarin enhanced chemosensitivity to cisplatin by inhibiting the expressions of ABCB1 and ABCG2 in cisplatin-resistant glioma cells. These findings proved that scutellarin suppressed metastasis and chemoresistance of glioma cells, suggesting that scutellarin might be a new therapeutic agent for the glioma treatment.

Supplementary material

Detection of synergistic effects of cisplatin with scutellarin.

Notes: (A, B) U87/DDP and U251/DDP cells were treated with scutellarin (50 or 100 µM) for 48 hours, cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (C, D) Drug synergism is expressed as fraction of affected curves and combination index (CI) plots in U87/DDP and U251/DDP cells. CI as an indicator of synergistic effects of cisplatin and scutellarin (additive effect, CI =0.9–1.1; slight synergism, CI =0.7–0.9; synergism, CI =0.3–0.7; strong synergism, CI =0.1–0.3). (E) Effect of scutellarin on cell toxicity in normal human astrocytes.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ho VK, Reijneveld JC, Enting RH, et al. Changing incidence and improved survival of gliomas. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(13):2309–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posti JP, Bori M, Kauko T, et al. Presenting symptoms of glioma in adults. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131(2):88–93. doi: 10.1111/ane.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koekkoek JA, Dirven L, Sizoo EM, et al. Symptoms and medication management in the end of life phase of high-grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol. 2014;120(3):589–595. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Groot JF. High-grade gliomas. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015;21:332–344. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000464173.58262.d9. Neuro-oncology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafazalla K, Sahgal A, Jaja B, Perry JR, Das S. Procarbazine, CCNU and vincristine (PCV) versus temozolomide chemotherapy for patients with low-grade glioma: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2018;9(72):33623–33633. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayak L, de Groot J, Wefel JS, et al. Phase I trial of aflibercept (VEGF trap) with radiation therapy and concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide in patients with high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2017;132(1):181–188. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theeler BJ, Ellezam B, Yust-Katz S, Slopis JM, Loghin ME, de Groot JF. Prolonged survival in adult neurofibromatosis type I patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab. J Neurol. 2014;261(8):1559–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hombach-Klonisch S, Mehrpour M, Shojaei S, et al. Glioblastoma and chemoresistance to alkylating agents: Involvement of apoptosis, autophagy, and unfolded protein response. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;184:13–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staberg M, Rasmussen RD, Michaelsen SR, et al. Targeting glioma stem-like cell survival and chemoresistance through inhibition of lysine-specific histone demethylase KDM2B. Mol Oncol. 2018;12(3):406–420. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia L, Tian Y, Chen Y, Zhang G. The silencing of LncRNA-H19 decreases chemoresistance of human glioma cells to temozolomide by suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:313–321. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S154339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Wang L, Ma Q. Clinical benefits and pharmacology of scutellarin: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;190:105–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Huang D, Gao Z, Chen Y, Zhang L, Zheng J. Scutellarin inhibits the growth and invasion of human tongue squamous carcinoma through the inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and αvβ6 integrin. Int J Oncol. 2013;42(5):1674–1681. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ke Y, Bao T, Wu X, et al. Scutellarin suppresses migration and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the STAT3/Girdin/Akt activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;483(1):509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu PT, Mao M, Liu ZG, Tao L, Yan BC. Scutellarin suppresses human colorectal cancer metastasis and angiogenesis by targeting ephrinb2. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(11):5094–5104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun CY, Zhu Y, Li XF, et al. Scutellarin Increases Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis and Autophagy to Overcome Cisplatin Resistance in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer via ERK/p53 and c-met/AKT Signaling Pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:92. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao C, Zhou Y, Jiang Z, et al. Cytotoxic and chemosensitization effects of Scutellarin from traditional Chinese herb Scutellaria altissima L. in human prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(3):1491–1499. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y, Zhang S, Tu J, et al. Novel function of scutellarin in inhibiting cell proliferation and inducing cell apoptosis of human Burkitt lymphoma Namalwa cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(12):2456–2464. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.693177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu H, Zhang S. Scutellarin-induced apoptosis in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells via a STAT3 pathway. Phytother Res. 2013;27(10):1524–1528. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein CA. Cancer. The metastasis cascade. Science. 2008;321(5897):1785–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1164853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yilmaz M, Christofori G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28(1–2):15–33. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brabletz T. EMT and MET in metastasis: where are the cancer stem cells? Cancer Cell. 2012;22(6):699–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szakács G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman MM. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(3):219–234. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang L, Graham PH, Ni J, et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in the treatment of prostate cancer radioresistance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96(3):507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(3):R83–R99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polivka J, Janku F. Molecular targets for cancer therapy in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142(2):164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang TT, Sarkaria SM, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS. Targeted therapy for malignant glioma patients: lessons learned and the road ahead. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(3):500–512. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondo Y, Hollingsworth EF, Kondo S. Molecular targeting for malignant gliomas (Review) Int J Oncol. 2004;24(5):1101–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detection of synergistic effects of cisplatin with scutellarin.

Notes: (A, B) U87/DDP and U251/DDP cells were treated with scutellarin (50 or 100 µM) for 48 hours, cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. (C, D) Drug synergism is expressed as fraction of affected curves and combination index (CI) plots in U87/DDP and U251/DDP cells. CI as an indicator of synergistic effects of cisplatin and scutellarin (additive effect, CI =0.9–1.1; slight synergism, CI =0.7–0.9; synergism, CI =0.3–0.7; strong synergism, CI =0.1–0.3). (E) Effect of scutellarin on cell toxicity in normal human astrocytes.