Abstract

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) spend significant time and resources to track influenza vaccination coverage each influenza season using national surveys. Emerging data from social media provide an alternative solution to surveillance at both national and local levels of influenza vaccination coverage in near real time.

Objectives

This study aimed to characterise and analyse the vaccinated population from temporal, demographical and geographical perspectives using automatic classification of vaccination-related Twitter data.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we continuously collected tweets containing both influenza-related terms and vaccine-related terms covering four consecutive influenza seasons from 2013 to 2017. We created a machine learning classifier to identify relevant tweets, then evaluated the approach by comparing to data from the CDC’s FluVaxView. We limited our analysis to tweets geolocated within the USA.

Results

We assessed 1 124 839 tweets. We found strong correlations of 0.799 between monthly Twitter estimates and CDC, with correlations as high as 0.950 in individual influenza seasons. We also found that our approach obtained geographical correlations of 0.387 at the US state level and 0.467 at the regional level. Finally, we found a higher level of influenza vaccine tweets among female users than male users, also consistent with the results of CDC surveys on vaccine uptake.

Conclusion

Significant correlations between Twitter data and CDC data show the potential of using social media for vaccination surveillance. Temporal variability is captured better than geographical and demographical variability. We discuss potential paths forward for leveraging this approach.

Keywords: health informatics, world wide web technology, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study shows how to measure influenza vaccination uptake through Twitter, which has advantages and disadvantages compared with traditional survey methods.

The signal from Twitter is available in real time and has potential to be localised to specific geographical locations.

While Twitter can be considered ‘big data’, the sample size is more limited when narrowed to specific populations.

Certain vulnerable populations, including children and older adults, are under-represented in Twitter data.

Introduction

The Advisory Council for Immunisation Practices at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends annual influenza vaccination for all healthy adults.1 Furthermore, CDC urges individuals to get vaccinated early in the influenza season, from October to January.2 Yet, it can be difficult for researchers and practitioners working to improve influenza vaccine uptake to get accurate information in real time. Existing influenza immunisation surveillance techniques have known limitations: traditional survey-based methods are time-consuming and expensive, and newer reimbursement-based systems fail to accurately capture a representative sample of population.3

Two national surveillance systems enable public health professionals to access information on influenza vaccine uptake in the USA. The most accessible of these systems is the CDC’s FluVaxView, which aggregates uptake data from several national surveys.4 The CDC data provide accurate estimates of vaccine uptake, although with some time lag. The earliest reports are only available after influenza seasons typically peak, and final estimates are generally published at the start of the following influenza season in September or October. Additionally, the panel surveys that inform the reports are expensive, take months to administer and process, and may undersample populations without a landline phone, particularly minority populations, young adults and adults living in urban areas.5 6 A second system,7 provided by the National Vaccine Programme Office, uses an online tool to ‘live-track’ influenza vaccination insurance claims from Medicare beneficiaries. While this system reduces time lag between vaccination and reporting, it only captures the population enrolled in Medicare, adults over age 65 and those under 65 living with disabilities.7 Social media data have been used in new tools for infectious disease surveillance, particularly for seasonal and pandemic influenza.8–10Using data from social media platforms (like Twitter or Facebook), search engines (like Google) and other internet-based resources (like blogs), researchers have been able to track the spread of disease in real time with relatively high accuracy.9 A recent meta-analysis of social media influenza surveillance efforts found that in a comparison to national health statistics (primarily from the CDC), correlation between social media data and national statistics ranged from 0.55 to 0.95,11 12 and the majority of projects were able to predict outbreaks more quickly than traditional surveillance methods.10 Of these studies, the most accurate systems have harnessed natural language processing methods to identify relevant tweets. However, few of these tools have been fully integrated into public health practice.

With the development of new tools and techniques, social media data have the potential to similarly inform the practice of influenza immunisation surveillance. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have attempted to use social media data to track influenza vaccine intentions and uptake at the national level. To date, efforts to track influenza vaccination through social media have been much less frequent than efforts to track disease. Researchers are more likely to focus on the use of social media as a health communication tool than to explore the potential for immunisation surveillance.13 Some studies have been able to use social media data to track vaccine sentiment and general attitudes towards vaccines.14–16 Others have focused on the spread of vaccine sentiment across online social networks.17 18 Some vaccine-specific studies have also attempted to use social media to identify geographical differences in vaccine uptake.19 20 The possibility of efficiently tracking influenza immunisation in real time is promising, but the true value of any new data source is limited without validation against known metrics.14 21 22 To successfully use social media data in immunisation surveillance efforts, an important first step is to validate observed trends against national survey data. In this study, we sought to validate observed patterns from Twitter, using tweets expressing either intention to seek immunisation or receipt of influenza immunisation, against influenza immunisation data from the CDC for four consecutive influenza seasons from 2013 to 2017.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

This study did not involve patients.

Data

Twitter data

We continuously collected tweets containing the terms ‘flu’ or ‘influenza’ since 2012 using the Twitter streaming Application Programming Interface, as part of data described in our team’s prior work on Twitter-based health surveillance.23 For this study, we filtered influenza-related tweets containing at least one vaccine-related term (‘shot(s)’, ‘vaccine(s)’ and ‘vaccination’). We then inferred the US state for tweets using the Carmen geolocation system,24 and the gender of each Twitter user of the data set using the Demographer tool.25 The Carmen tool infers locations of tweets by three main sources, coordinates of tweets, places name of tweets and locations in user profiles, and most often represents the home location of the user rather than their location while tweeting. The Demographer tool infers binary genders of Twitter users by the names of their profiles. We removed retweets, non-English tweets and tweets not located in the USA. We obtained 1 124 839 tweets from 742 802 Twitter users covering 4 consecutive influenza seasons from 2013 to 2017. More details can be found in the online supplementary files (A1 and A2).

bmjopen-2018-024018supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

In addition to tweets about influenza vaccination, we also collected a random sample of tweets from all of Twitter. This was used to adjust the vaccine counts by time, location and demographics, as described below. The random sample includes approximately 4 million tweets per day since 2011.

CDC data

We used CDC data on influenza vaccination of the four influenza seasons for validating our approaches. The CDC data were downloaded from the CDC’s FluVaxView system.4 These data include vaccination coverage by month, states and geographical regions as defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The CDC’s estimates are based on several national surveys: the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (which targets adults), the National Health Interview Survey and the National Immunisation Surveys (which focuses on children). In this study, we use the CDC data for adults (≥18 years old) across all racial/ethnic groups. The CDC reports the ‘sex’ of the respondents, although the underlying surveys ask for ‘gender’ rather than sex,26 27 making this variable comparable to our definition of gender in Twitter.

Automated classification

In our study, we used natural language processing techniques to preprocess and encode tweets into feature vectors, then used the vectors to build machine learning classifiers to automatically categorise Twitter messages that express vaccination behaviour. Tweets were classified into yes or no labels in response to the question, ‘Does this message indicate that someone received, or intended to receive, a influenza vaccine?’ Specifically, we randomly sampled 10 000 tweets from our collected data from 2012 to 2016 and then used a crowdsourcing platform to annotate the 10 000 tweets,28 using quality control measures to ensure accurate annotations. The classifiers were trained by the annotated tweets.

The best-performing classification model was a convolutional neural network, which had a precision (the proportion of tweets classified as vaccine intention/receipt that were correctly classified) of 89.4% and recall (the proportion of vaccine intention/receipt tweets that were identified by the classifier) of 80.0%, measured using nested fivefold cross-validation. This classifier was applied to the full data set of 1 124 839 tweets, of which 366 698 were classified as expressing that someone received or intended to receive an influenza vaccine. More details of preprocessing and encoding tweets, and building and selecting machine learning models, can be found in the online supplementary file (A.2) as well as in our prior preliminary work using simpler models.29

Trend extraction and validation

To evaluate the reliability of the Twitter classification model as a source for vaccination surveillance, we compared the Twitter data to CDC data along three dimensions: time (by month), location (by US state and region) and demographics (by gender). Specifically, CDC FluVaxView provides the monthly percentage of American adults who received an influenza vaccination in a given month in each state, as well as the percentage of Americans who report vaccination in different demographic groups each influenza season.

To extract trends over time, we computed the number of vaccine intention/receipt tweets in each month per season, excluding June (the CDC does not report data for June). We only included tweets geolocated to the USA. To adjust for variations in Twitter over time, we divided the monthly counts by the number of tweets in the same month from the large random sample of tweets.8 In addition to monthly rates for direct comparison to CDC, we also calculated weekly tweet rates, providing estimates at a finer time granularity than reported by the CDC. For monthly time series data, we applied an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model and linear regression to estimate the CDC data from the Twitter data.30

To extract trends by location, we computed the number of intention/receipt tweets in each of the 10 HHS regions and each of the 50 US states. We created per-capita estimates by dividing each count by the number of tweets from the same region or state from the random sample of tweets.

To extract trends by gender, we computed the number of intention/receipt tweets identified as male or female, divided by the corresponding counts from the random sample. We computed this proportion within each US state before aggregating the counts from all states, to additionally adjust for gender variation across location. We provided detailed validation steps and additional experiments in online supplementary file A.3.

Confidence intervals

We present 95% CIs for all results. There are two sources of variability we must account for when constructing CIs. One source is the set of points included in the correlation. The other is the set of tweets used to estimate the level of vaccine intention in each group. When estimating values within fine-grained groups, such as specific US states, the number of tweets can be small, leading to high variability in the estimates that propagates to the estimate of the correlation.

To address these issues, we construct CIs using bootstrap resampling.31 We perform sampling at two levels. First, we sample the set of tweets used to calculate the estimate in each group (eg, the tweets in a specific month or location). We then sample the set of points that are included in the calculation of the correlation (eg, the set of months). The CIs are constructed from 100 bootstrap samples.

Results

Activity by time

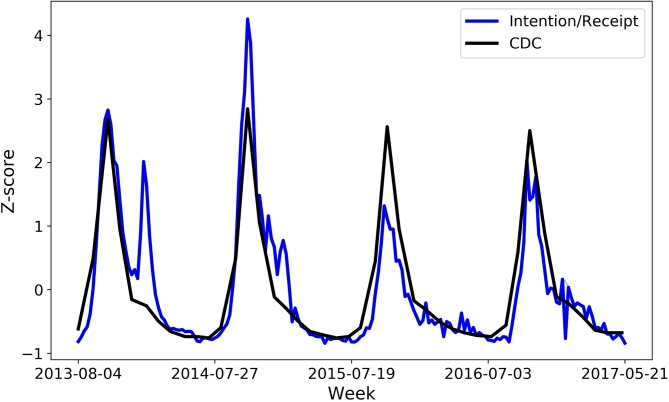

Table 1 shows the correlation between the classified tweets and CDC data from the ARIMA results along with 95% CIs. Figure 1 shows the values from both data sources over time, standardised with Z-scores. While the CDC data are only available by month, we show Twitter counts by week (Sunday to Saturday) to illustrate the finer temporal granularity that is possible. In both data sets, there are seasonal peaks every October, when influenza vaccines are distributed in the USA. While the overall shapes are very similar, the Twitter data sometimes show rises later in the influenza season that do not correspond to a similar rise in the CDC data, especially in the 2013–2014 season, which results in the lowest correlation.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations (95% CI) by month in each influenza season

| All seasons | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | |

| Monthly | 0.799 (0.797 to 0.801) |

0.644 (0.639 to 0.647) |

0.950 (0.948 to 0.951) |

0.909 (0.905 to 0.913) |

0.910 (0.909 to 0.912) |

Figure 1.

Monthly levels of influenza vaccination activity as measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) versus Twitter.

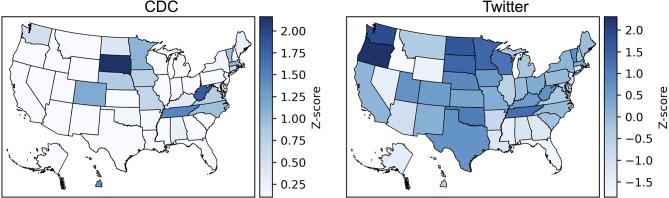

Activity by location

The prevalence of tweets mentioning vaccine intention/receipt in each location is shown in figure 2, where darker colour indicates more frequent vaccine mentions. We observe that states in the northwest, especially Washington and Oregon, have higher rates than southeastern states, such as Florida and Alabama. There is a moderate correlation between the geographical patterns in the Twitter data compared with the CDC data, with a higher correlation at the HHS region level than at the state level (table 2). The strength of the correlations varies by season, with much stronger correlations in the first two seasons than the latter two seasons.

Figure 2.

Levels of influenza vaccination activity per US state as measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) versus Twitter.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations (95% CI) by geography in each season

| All seasons | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | |

| State | 0.387 (0.362 to 0.394) |

0.300 (0.261 to 0.308) |

0.214 (0.193 to 0.243) |

0.051 (0.015 to 0.057) |

0.025 (0.002 to 0.040) |

| HHS region | 0.467 (0.445 to 0.483) |

0.690 (0.650 to 0.714) |

0.573 (0.539 to 0.600) |

0.137 (0.090 to 0.179) |

0.244 (0.213 to 0.272) |

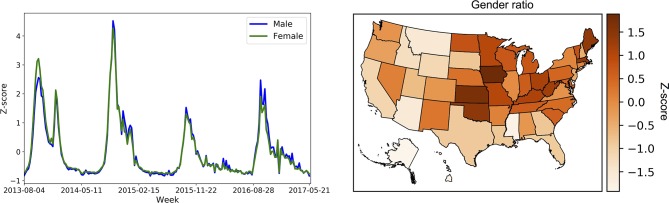

Activity by gender

Female users are much more likely to tweet about vaccine intention/receipt than male users on Twitter. The female-to-male ratios in each of the four seasons are (with 95% CIs), respectively, 1.97 (1.96 to 1.98), 1.73 (1.72 to 1.74), 1.59 (1.58 to 1.59) and 1.47 (1.46 to 1.48). This ratio is higher than in the CDC data (1.18, 1.17, 1.19 and 1.20). However, the two data sources are in relative agreement: the vaccination rate is higher among females than males. For example, in the 2016–2017 influenza seasons, the CDC reported that among American adults, 47.0% of women were vaccinated for influenza, compared with 39.3% of men.

We visualised the gender weekly trends and gender ratio of vaccine coverage across locations in figure 3. The plot of gender weekly trends shows the volume of vaccine intention/receipt tweets over time. The gender ratio has also decreased steadily over time in the Twitter data, while it has stayed fairly constant in the CDC data. The plot of gender ratio shows the female-to-male ratio of vaccine intention/receipt tweets within each US state, with darker colour indicating a higher ratio. For example, the figure shows that West Virginia has more females mentioning influenza vaccine behaviour than males. We provided additional analyses in the online supplementary file A.4.

Figure 3.

Levels of influenza vaccination activity of male versus female users in Twitter across time (left) and location (right).

Discussion

By using natural language processing techniques, Twitter data can be effectively analysed to identify meaningful information about influenza vaccination intentions and behaviours at the population level. Our key finding is the strong correlation between monthly Twitter-based estimates of vaccination uptake and official CDC uptake estimates. Additionally, exploratory analysis suggests that natural language processing tools can be developed to further investigate significant patterns in self-reported vaccine uptake by time, location and demographics.

Traditionally, surveillance efforts have focused on monthly or yearly data. Twitter data allow for greater flexibility and specificity when assessing temporal trends in vaccination. For example, this study shows that it is possible to extract weekly data in addition to monthly estimates. Although we are unable to compare our weekly counts to a validated national metric, we observed high week-to-week variability in general influenza vaccine tweets before applying a classifier to filter out irrelevant tweets, but a relatively consistent and predictable pattern in week-to-week tweets indicating vaccine intention and receipt, suggesting that the classifiers are reducing noise at this granularity.

It is possible to capture geographical variability in Twitter data using the Carmen tool. Our results suggest some similarities with the CDC FluVaxView maps, but the associations are not strong enough to make definitive conclusions based on geography. There may be local level trends that contribute to these observed patterns. While the value of this information is limited, it does demonstrate the potential for more detailed geographical analysis in the future, especially as the number of Twitter users continues to climb.

Demographical classifiers are still under development. We were able to use the Demographer tool to identify the gender of the person tweeting. Our results suggest that there are significantly more tweets indicating intention to vaccinate coming from females. CDC data suggest that this may be accurate, with significantly more females reporting vaccination than males according to FluVaxView. However, the gender gap in Twitter narrowed over the course of the four seasons in our study period, despite staying constant according to the CDC. Other important demographic attributes, like age, are challenging to classify and therefore not considered in this study.32 Further refinement of demographic classifiers is necessary.

There are limitations to working with social media data. While social media is considered ‘big data’, we nevertheless ran into challenges with sample size. While the full data set is indeed large, with over 1 million tweets, only 33.8% of those tweets can be resolved to the USA, and each experiment further filters down the data into smaller groups. For example, if tweets are counted by month within each US state, then the data need to be split into 600 partitions (12 months times 50 states) within each year. This has an observable effect of the validity of the results: the correlations between Twitter and CDC are very strong at the national level, but weaker at the regional level and weaker still at the state level. Sample size of tweets may also explain why the geographical correlations between Twitter and CDC (table 2) were strong in 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 than in 2015–2016 and 2016–2017: the first two seasons contain 25.8% more geolocated tweets than the latter two seasons.

Errors in the natural language classifiers also limit overall accuracy of the approach. We investigated why the correlation with CDC was substantially lower in the 2013–2014 season compared with others, and while there is no single conclusive explanation, we observed that the classifiers misidentified influenza-related tweets as indicating vaccine intentions during the peak of the influenza season in January 2014, such as tweets expressing regret about not being vaccinated. This type of error was common during this month, resulting in an spike in classified tweets that did not correspond with a true rise in vaccine uptake.

These data limitations affect all social media focused research. However, among studies that use natural language processes to study social media data, this is one of the first studies to track vaccination uptake. Our focus on messages that explicitly indicated intention or receipt of vaccination was unique. Existing research has focused on vaccine attitudes or sentiments alone, or substitutes other measures as a proxy for behaviour.33 For example, Salanthé and Khandelwal’s assessment of vaccine-related Tweets during the H1N1 influenza pandemic found strong correlation between vaccine sentiment expressed in tweets and CDC vaccine uptake rates.17 Another study by Dunn et al mapped exposure to negative information about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines on Twitter to state-level vaccine uptake rates.20 A more recent study from Tangherlini et al focused on instances of parents opting-out of immunisations by identifying narratives describing vaccine exemptions on ‘Mommy blogs’.34

Our results suggest that self-report data from Twitter can enrich the practice of influenza immunisation surveillance and inform influenza vaccination campaigns. To date, the majority of social media surveillance research has been conducted without the involvement of local, state or governmental agencies.10 Indeed, most efforts to include public health practitioners in social media research have focused on health communications efforts.35 36 By using an adaptable machine learning technique, research questions can be tailored to suit the needs of specific projects or organisations. For example, while we focused on estimating vaccination coverage from FluVaxView, future work could use this data in a study design that is focused on supporting decision making.37 It may also be possible to use social media to track the impact and effectiveness of vaccines in a community, as early work suggests.38

Development of demographical classifiers for factors such as age and race/ethnicity is an important next step. One advantage of using Twitter is the ability to capture behaviours from a broader range of adults, especially from groups that may be difficult to reach using traditional surveys, including young adults and members of minority groups such as African Americans and Hispanics.30 31 While all groups fail to reach the Healthy People 2020 recommendation of 70% uptake, these same populations (young adults and racial/ethnic minorities) are also the least likely to be immunised against seasonal influenza.39–41

Incorporating self-report social media data may allow researchers and practitioners to respond to emerging health issues in new and innovative ways, but the progress depends on the ability to integrate novel methods into existing frameworks and to validate new data streams against reliable metrics. True success will depend on the use of novel techniques to measure positive changes in population health.42

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

An early version of this research was presented at the AAAI Joint Workshop on Health Intelligence (W3PHIAI) in February 2017.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: XH, MCS, DAB, MD, SCQ and MJP contributed to the design of the study. XH, JC, MD and MJP contributed to data collection. XH, MCS, JC, DAB and MJP performed data analysis. XH, AMJ, DAB, SCQ and MJP interpreted the results. All authors contributed to the editing of this manuscript.

Funding: Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under award number R01GM114771 to DAB and SCQ and by the National Science Foundation under award number IIS-1657338 to XH and MJP.

Competing interests: MD and MJP hold equity in Sickweather Inc. MD has received consulting fees from Bloomberg LP, and holds equity in Good Analytics Inc. These organisations did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval: This work was conducted under Johns Hopkins University Homewood IRB No. 2011123: ’Mining Information from Social Media', which qualified for an exemption under category 4.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All Twitter data used in this study are available in the following repository: https://figshare.com/articles/Flu_Vaccine_Tweets/6213878 This repository contains the annotations for training the classifiers, as well as the classifier inferences on the full data set. This also contains the extracted metadata, including demographics and location. In accordance with the Twitter terms of service, raw tweets are not shared, but identifiers are shared which can be used to download the tweets.

References

- 1. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. . Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices-United States, 2017-18 influenza season. Am J Transplant 2017;17:2970–82. 10.1111/ajt.14511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. CDC. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/rr/rr6602a1.htm (Accessed 8 Mar 2018).

- 3. Santibanez T. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2016-17 influenza season. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1617estimates.htm (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza Vaccination Coverage | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza | CDC. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/index.htm (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 5. Keeter S. The impact of cell phone noncoverage bias on polling in the 2004 presidential election. Public Opin Q 2006;70:88–98. 10.1093/poq/nfj008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iachan R, Pierannunzi C, Healey K, et al. . National weighting of data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:155 10.1186/s12874-016-0255-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Department of Health and Human Services. Flu vaccination trends. 2017. https://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/resources/flu/index.html

- 8. Broniatowski DA, Paul MJ, Dredze M. National and local influenza surveillance through Twitter: an analysis of the 2012-2013 influenza epidemic. PLoS One 2013;8:e83672 10.1371/journal.pone.0083672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Velasco E, Agheneza T, Denecke K, et al. . Social media and internet-based data in global systems for public health surveillance: a systematic review. Milbank Q 2014;92:7–33. 10.1111/1468-0009.12038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charles-Smith LE, Reynolds TL, Cameron MA, et al. . Using social media for actionable disease surveillance and outbreak management: a systematic literature review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139701 10.1371/journal.pone.0139701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corley CD, Cook DJ, Mikler AR, et al. . Text and structural data mining of influenza mentions in Web and social media. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:596–615. 10.3390/ijerph7020596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collier N, Son NT, Nguyen NM. OMG U got flu? Analysis of shared health messages for bio-surveillance. J Biomed Semantics 2011;2:S9 10.1186/2041-1480-2-S5-S9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Odone A, Ferrari A, Spagnoli F, et al. . Effectiveness of interventions that apply new media to improve vaccine uptake and vaccine coverage. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015;11:72–82. 10.4161/hv.34313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dredze M, Broniatowski DA, Hilyard KM. Zika vaccine misconceptions: a social media analysis. Vaccine 2016;34:3441–2. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Powell GA, Zinszer K, Verma A, et al. . Media content about vaccines in the United States and Canada, 2012-2014: an analysis using data from the Vaccine Sentimeter. Vaccine 2016;34:6229–35. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kang GJ, Ewing-Nelson SR, Mackey L, et al. . Semantic network analysis of vaccine sentiment in online social media. Vaccine 2017;35:3621–38. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salathé M, Khandelwal S. Assessing vaccination sentiments with online social media: implications for infectious disease dynamics and control. PLoS Comput Biol 2011;7:e1002199 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salathé M, Vu DQ, Khandelwal S, et al. . The dynamics of health behavior sentiments on a large online social network. EPJ Data Sci 2013;2:4 10.1140/epjds16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nelson EJ, Hughes J, Oakes JM, et al. . Estimation of geographic variation in human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in men and women: an online survey using facebook recruitment. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e198 10.2196/jmir.3506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dunn AG, Surian D, Leask J, et al. . Mapping information exposure on social media to explain differences in HPV vaccine coverage in the United States. Vaccine 2017;35:3033–40. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tufekci Z. Big questions for social media big data: representativeness, validity and other methodological pitfalls. ICWSM 2014;14:505–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen R, Ruths D. Classifying political orientation on Twitter: It’s not easy!. ICWSM 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paul MJ, Dredze M. Discovering health topics in social media using topic models. PLoS One 2014;9:e103408 10.1371/journal.pone.0103408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dredze M, Paul MJ, Bergsma S, et al. . “Carmen: a twitter geolocation system with applications to public health,”. AAAI workshop on expanding the boundaries of health informatics using AI 2013;23:45. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knowles R, Carroll J, Dredze M. Demographer: extremely simple name demographics. Proceedings of the First Workshop on NLP and Computational Social Science 2016:108–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. National Immunization Surveys (NIS), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system questionaires, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Callison-Burch C, Dredze M, 2010. Creating speech and language data with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Creating Speech and Language Data with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang X. Examining patterns of influenza vaccination in social media. AAAI Joint Workshop on Health Intelligence 2017:542–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franke J, Härdle WK, Hafner CM. ARIMA time series models Statistics of financial markets: an introduction. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2011:255–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Efron B, Tibshirani R. [Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy]: Rejoinder. Statistical Science 1986;1:77 10.1214/ss/1177013817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flekova L, Carpenter J, Giorgi S, et al. . D. Preo\ctiuc-Pietro, “Analyzing biases in human perception of user age and gender from text,. Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2016;1:843–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Du J, Xu J, Song HY, et al. . Leveraging machine learning-based approaches to assess human papillomavirus vaccination sentiment trends with Twitter data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017;17:69 10.1186/s12911-017-0469-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tangherlini TR, Roychowdhury V, Glenn B, et al. . “Mommy Blogs” and the vaccination exemption narrative: results from a machine-learning approach for story aggregation on parenting social media sites. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2016;2:e166 10.2196/publichealth.6586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhou X, Coiera E, Tsafnat G, et al. . Using social connection information to improve opinion mining: Identifying negative sentiment about HPV vaccines on Twitter. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;216:761–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGregor KA, Whicker ME. Natural language processing approaches to understand HPV vaccination sentiment. Journal of Adolescent Health 2018;62:S27–S28. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.055 29455714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alberti KP, Guthmann JP, Fermon F, et al. . Use of Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) to estimate vaccination coverage helps guide future vaccination efforts. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008;102:251–4. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wagner M, Lampos V, Yom-Tov E, et al. . Estimating the population impact of a new pediatric influenza vaccination program in england using social media content. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e416 10.2196/jmir.8184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krogstad JM. Social media preferences vary by race and ethnicity. 2015. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/02/03/social-media-preferences-vary-by-race-and-ethnicity/

- 40. CDC. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2016-17 Influenza Season. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1617estimates.htm#age-group-adults (Accessed 8 Mar 2018).

- 41. HealthyPeople. Immunization and infectious diseases. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases (Accessed 9 Mar 2018).

- 42. Mooney SJ, Westreich DJ, El-Sayed AM. Epidemiology in the era of big data. Epidemiology 2015;26:390–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024018supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)