Abstract

Neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders (NPD) has been practiced for >80 years. However, the interests have waxed and waned, from 1000s of surgeries in 1940–1950s to handful of surgery in 60–80s. This changed with the application of deep brain stimulation surgery, a surgery, considered to be “reversible” there has been a resurgence in interest. The Indian society for stereotactic and functional neurosurgery (ISSFN) and the world society for stereotactic and functional neurosurgery took the note of the past experiences and decided to form the guidelines for NPD. In 2011, an international task force was formed to develop the guidelines, which got published in 2013. In 2018, eminent psychiatrists from India, functional neurosurgeon representing The Neuromodulation Society and ISSFN came-together to deliberate on the current status, need, and legal aspects of NPD. In May 2018, Mental Health Act also came in to force in India, which had laid down the requirements to be fulfilled for NPD. In light of this after taking inputs from all stakeholders and review of the literature, the group has proposed the guidelines for NPD that can help to steer these surgery and its progress in India.

Keywords: Depression, guidelines for surgery, Indian guidelines, obsessive-compulsive disorder, surgery, Tourette syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Surgery for neuropsychiatric disorders has a checkered past. The pendulum has swung from Egaz Moniz and Lima being awarded a Nobel Prize for their discovery of frontal leukotomy, to the surgery being completely banned in several countries, including developed countries such as Sweden and Japan. The Indian Mental Health Care Act 2017 was passed in the parliament and came into force in May 2018. In this act, surgery for neuropsychiatric disorders is discussed separately, and regulations for the same have been provided.[1]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2009, a group of psychiatrists and neurosurgeons met in Mumbai, to lay down preliminary guidelines for surgical interventions in neuropsychiatric disorders. Following these guidelines, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) and Jaslok Hospital performed surgical interventions in a few patients with psychiatric conditions.[2] In 2013, a consensus guideline paper was published, authored by several international stereotactic and functional neurosurgical societies (including the World Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery) and World Psychiatric Association.[3] The Indian Psychiatric Society's (IPS) clinical practicing guidelines for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) published in 2017 discusses recommendations for neurosurgical interventions for the treatment of refractory OCD.[4]

In this background, several psychiatrists and neurosurgeons thought that it was important to review the current status of the surgical and noninvasive stimulation (excluding electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]) therapies and their role in the management of psychiatric disorders. The IPS, Indian Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, and The Neuromodulation Society decided to conduct, an “Academic Conclave on Neuropsychiatric Interventions” to initiate a multidisciplinary discussion on indications, current status, Indian practices, ethical considerations, etc., for two main noninvasive interventions, namely, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation as well as surgical interventions. Around 75 eminent psychiatrists and neurosurgeons, the leaders and opinion makers in their respective field were invited to participate in this meeting. A 300-page dossier consisting of recently published articles in noninvasive stimulation and surgical therapy was prepared by the first author and circulated to all members in advance. This was to aid them to prepare for the discussion. The meeting was divided into two parts as follows: in the first part, the current status of the interventions (including Indian scenario) was discussed, and in the second part, various aspects of the guidelines for these interventions was discussed. These discussions were transcribed by three different doctors to capture the essence of all comments.

At conclusion of the conclave, it was decided that a core group will formulate consensus statement as a first draft. This draft will be circulated to select group of office bearers of the respective societies and academicians for a review. Following their comments, the authors will redraft/amend the guidelines and then circulate to a larger group for their inputs and comments, which will then be finalized. The final draft will try to balance all comments with the current literature before being sent for publication.

The guidelines published herewith, recognize the Declaration of Helsinki, issued by the World Medical Association in 1964, amended several times, as the fundamental document in the field of ethics in biomedical research. The guidelines have been drafted after an extensive review of the published literature on these interventions, including international guidelines that have been adopted by several countries, legislation of various countries, and ethical considerations. The consensus paper published by Nuttin et al.[3] has been heavily relied on as two developed countries (the USA and UK) have used it to frame their guidelines. We have adopted this to the Indian context, considering available resources with social and moral sensitivities. We have adopted a pragmatic view to making the guidelines directive and not restrictive.

Review of literature and current status of therapy

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Lesioning of the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) by Gamma Knife (GK) or radiofrequency (RF) has been practiced since 1949 for refractory OCD. Rück et al. reported a long-term follow-up of 25 cases of GK and RF capsulotomy. They found that 48% of their patients had >35% improvement.[5] They did not find any difference between the two modalities. In another study of 37 patients, Liu et al. found that the number of responders increased over time. At 5 years, 73% of patients had >50% and 16% of patients had between 20% and 50% reduction in the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Y-BOCS) scores.[6] In a recent literature review, Pepper et al. compared the outcome of capsulotomy with deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS) area. They found that patients with capsulotomy had 51% improvement in their Y-BOCS scores as compared to DBS patients, who had 40% improvement. The remission rates in severe and extremely severe OCD (Y-BOCS >24) were significantly higher in the capsulotomy group.[7] Most of the reports on capsulotomy had Class II or IV evidence.

Anterior cingulotomy is another ablative procedure for OCD that has been extensively practiced, especially in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), USA. The procedure targets the anterior cingulate gyrus and the cingulum bundle, due to its putative role in the pathogenesis of OCD. A recent review of 64 patients who underwent anterior cingulotomy at the MGH found that 35% of patients had full response and 7% had a partial response. A re-surgery within nonresponders with either anterior cingulotomy or subcaudate tractotomy increased the rates to 47% and 22% for full and partial response.[8] A similar response rate was found in an independent sample of 17 patients in South Korea.[9]

Nuttin et al. reported a case series of four patients undergoing DBS of ALIC for OCD, with three of the four patients showing improvement.[10] It was later recognized that targeting the ventral aspects of the internal capsule including the adjacent VC/VS was associated with improved outcome. In a follow-through multicenter study, they found that there was an improvement in Y-BOCS score from a mean of 34 (0.5) to 20 (2.4) 36 months postsurgery. Nineteen of the 26 patients implanted had an improvement of >25%, in their Y-BOCS scores.[11] Mallet et al. reported a double-blind, randomized, cross-over, multicenter study of subthalamic nucleus stimulation for OCD (denoted as Class I study), found 32% improvement in the mean Y-BOCS scores of 16 patients after active stimulation. The decrease in Y-BOCS scores was significantly greater during the active stimulation compared to sham stimulation.[12] There were two Class II study for DBS in OCD. Denys et al. reported on 16 patients, who underwent nucleus accumbens DBS, an open-label stimulation for 8 months, followed by double-blind cross over On-Off stimulation. This was followed by open-label phase. They found that there was 8.3-point reduction in the Y-BOCS score. During the open-label phase, there was >50% reduction (responders) in 9 of the 16 patients.[13] In a study by Huff et al. involving 10 patients undergoing unilateral nucleus accumbens stimulation, no difference in Y-BOCS scores between sham and actual stimulation was found, however, there was a statistically significant improvement during open-label phase compared to baseline.[14] Luyten et al. reported on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 17 cases of stimulation of Bed Nucleus of Stria Terminalis (BST). Of the 24 patients enrolled in the trial, 17 completed a 3 months cross-over phase of ON and OFF stimulation. They found 37% more reduction in the Y-BOCS in patients with ON stimulation over patients OFF stimulation. In the open-label follow-up, they found that there was a median reduction of 66% of Y-BOCS scores as compared to baseline at a 4-year follow-up (18 of the 24 patients).[15] There have been several case series (Class III evidence) depicting good response to DBS of the above targets.[11,16,17] A meta-analysis published by Alonso analyzed 31 studies with 116 patients. In the sixteen studies (with more than one case), the average reduction in Y-BOCS scores was 45% and the average percentage of responders were (defined as Y-BOCS reduction >30%) 60%.[18] In 2009, Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of Medtronic Activa DBS of ALIC under humanitarian device exemption. Mantione et al. showed that the acceptance and response to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) improved after DBS for OCD.[19]

Indian experience in obsessive-compulsive disorder

Doshi have operated eight patients of OCD. Three patients have undergone capsulotomy,[2] three have undergone nucleus accumbens lesioning, one patient has undergone nucleus accumbens DBS, and one has undergone DBS of BST. The mean Y-BOCS scores before surgery for this group were 35.5 which improved to 12.6. All patients had >50% improvement in their Y-BOCS scores (unpublished data). At NIMHANS, anterior cingulotomy was attempted in two patients with treatment-refractory OCD, one of whom remitted 2 years postsurgery, albeit with transient personality changes. Following this, the center switched over to GK capsulotomy, which has been conducted in six patients with treatment-refractory OCD till date. Three patients have a follow-up period of at least 12 months, of which one patient had a good response (60% decreases in Y-BOCS score), one patient had a partial response (33% decrease), and the other patient had no response following surgery. No postsurgical complications were noticed in any other patients (unpublished data).

Depressive disorder

DBS for major depressive disorder (MDD) has been attempted over VC/VS, subcallosal cingulate cortex, nucleus accumbens, medial forebrain bundle, and inferior thalamic peduncle. Majority of the earlier trials have been open-label uncontrolled trials, which have generally shown a positive response with DBS.[20] Malone examined the effect of VC/VS DBS in an open-label trial including 17 patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). At 12 months follow-up, the remission rate (defined as a score of 10 or lower for both the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale [MADRS][21] and Hamilton depression rating scale [HDRS])[22] was 41%.[23] In another trial, Lozano et al. showed that there was at least 50% reduction in HDRS in 43% of patients at 2 years.[24] Two large multisite randomized-controlled trials, one targeting subcallosal cingulate gyrus (SCCG), and the other targeting VC/VS, have raised some questions on efficacy and methodological issues related to DBS trials in psychiatric disorders. Both these trials failed to show statistically significant improvement in the depression scores on futility analysis and had to be abandoned before completion.[25,26] There were criticisms on the conduct of these trials with alternate explanations for not replicating the results seen in open-label studies. Some of these criticisms included titration period being too short, not enough time for cross-over study, targeting techniques, etc., Two recent trials employed a different methodology by switching the stimulator ON/OFF in a randomized manner for 3 months following a prolonged open-label run-in period. Puigdemont et al. conducted a study in patients who had sustained remission with open-label DBS of SCCG (5/8 patients). Among these five remitters, four patients remained in remission during 3 months in “ON” phase compared to 2/5 patients during the OFF phase.[27] In another study, Bergfeld et al. stabilized the patients with appropriate parameters of DBS of ventral ALIC for 52 weeks before randomized crossover ON/OFF phase. Here again, patients had a significantly lower score (HDRS 13.6 vs. 20.6) during stimulation ON as compared to stimulation OFF condition.[28] A recent meta-analysis of all sham-controlled trials of DBS in MDD (n = 190) found a higher response rate during active as compared to sham stimulation. The difference was not statistically significant after exclusion of crossover trials and analysis of parallel-arm trials alone. Further, there were no significant effects on other outcome measures such as functioning and quality of life. Given the inconsistent and poor quality of evidence, the recent Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments guidelines for treatment of mood disorders and other systematic reviews propose DBS as an experimental treatment for patients with severe, chronic TRD.[29]

Two targets are commonly used for ablative surgery in TRD. Anterior cingulate cortex and ALIC, the latter being also in vicinity to VC/VS target used for DBS. Christmas et al.[30] performed cingulotomy (5), capsulotomy (5), and vagal nerve stimulation (5) in TRD patients. They found that 40%, 60%, and only 20% of patients, respectively, improved (HDRS reduction >50%) following each procedure. They concluded that cingulotomy and capsulotomy are effective in the treatment of TRD. In a review of 800 cingulotomies by Cosgrove and Rauch, there were no deaths and only two infections.[31] Shields et al. reported on cingulotomy ± subcaudate tractotomy in 33 patients of TRD. They found 75% of patients improved, with 33% having more than 50% reduction in Beck's depression inventory.[32] Eljamel performed more precise cingulotomy on 30 patients. They reported a response rate of 60% of which 20% were in remission. They had a better outcome in cingulotomy patients as compared to capsulotomy.[33]

Indian experience in major depressive disorder

Doshi et al. have operated three patients with TRD using SCCG as their target. The follow-up ranges from 1.5 to 3 years. At the last follow-up, their HDRS (17) improved from 27 to 4, the Hamilton anxiety scores improved from 26 to 4 and two patients were only ON stimulation and OFF all medications (unpublished data).

Tourette syndrome

In a systematic review of case reports and case series on DBS for Tourette syndrome (TS),[34] Baldermann et al.[35] found 57 reports, which included 156 patients. There have been several targets for TS surgeries. The two widely used targets were antero-medial globus pallidus internus (amGPi) (44 cases) and centromedian parafascicular (cmPf) nucleus of the thalamus (78 cases). Only 4/57 studies met Class III evidence, rest all were Class IV. Overall, DBS resulted in a significant median improvement of 52.68% for the Global Yale global tic severity scale (YGTSS),[34] declining from a median score of 83.0 to 35.0 at last available follow-up. The analysis revealed that maximum improvement was reached by 1 month.[35] Two small RCTs on thalamic DBS in TS found significant benefits after “ON” stimulation compared to “OFF stimulation.”[36] In a randomized control trial of DBS of amGPi, Kefalopoulou et al. showed that, in 13/15 patients, YGTSS score improved from 81 (when stimulation was turned OFF) to 68 (with the stimulation turned ON).[37] Servello et al. reported 18 patients with cmPf DBS. The 2-year outcome, 15 of these 18 patients showed a 52% reduction of the YGTSS score.[38] There is an international registry of TS patients created by Michael Okun, which serves as a repository and data bank for all TS patients operated worldwide. A review of patients registered under the International DBS Database and Registry found that in the 171 registered with data available (age 13–58 years), the YGTSS score decreased from 75.01 (18.36) to 41.19 (20.00) 1 year after the surgery.[39] The commonly employed targets were the cmPf nucleus of the thalamus and anterior or posterior GPi. However, a recent double-blind RCT (n = 19) of DBS over aGPi found no significant difference in YGTSS scores between active versus sham stimulation groups after 3 months. There was a significant improvement after subsequent open-label stimulation for 6 months, thus suggesting that longer stimulation may be required for discerning the therapeutic effects of DBS in TS.[40] A group of experts participating in the TS Association International DBS Database/Registry provided an updated set of recommendations for DBS for TS in 2015. The recommendation states that age should no longer be a strict criterion and the merits of each case should be decided after screening by a multidisciplinary team. The rate of infections and device-related complications is high with TS compared to other indications, possibly secondary to the nature of symptoms. The expert recommendations suggest that the candidate's neuropsychological functioning and the psychosocial situation should be conducive for regular long-term follow-up. The group concluded that “After an extensive review of the literature and consensus among implanters of DBS, we conclude that TS DBS, though still evolving, is a promising approach for a subset of medication-refractory and severely affected patients”.[41]

Indian experience in Tourette syndrome

Doshi et al. reported on two cases of TS patients who underwent amGPi stimulation. The preoperative YGTSS scores were 80 and 70. The postoperative scores at 18 months follow-up were 22 and 34, respectively.[42] Dwarakanath et al. from NIMHANS, reported a DBS over amGPi in a patient with refractory TS, after which the YGTSS decreased from 100 to 27 at 9 months follow-up.[43]

Other disorders

There are some anecdotal reports for neurosurgical interventions in other psychiatric disorders such as anorexia nervosa,[44] substance dependence, and posttraumatic stress disorder.[45] In the absence of corroborati ng evidence regarding safety and efficacy, such interventions may be considered experimental at best and cannot be recommended as a part of clinical practice.

Psychosurgery and law

Earlier mental health legislation in India was completely silent on psychosurgery. However, the contemporary Mental Health Care Act, 2017 has placed some regulations on performing psychosurgery as a treatment for mental illness. This restriction on psychosurgery as a treatment for mental illness have been discussed in the section 96 of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017.[1]

The section 96 of the Act articulates that notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, psychosurgery shall not be performed as a treatment for mental illness unless:

The informed consent of the person on whom the surgery is being performed; and

Approval from the concerned Mental Health Board to perform the surgery has been obtained.

Recommendations to the Central Mental Health Authority regarding the Psycho-surgery by the Central rules drafting committee

The Central Rules Drafting Committee has recommended regulations to the Central Mental Health Authority Under section 122, sub-section (2), Clause (n) read with sub-section (2) of section 96 and sub-section (8) of section 97. In principle, the committee has recommended that the treating psychiatrist should submit copies of informed consent, patient's medical records, clinical summary with justification for surgery and report of an independent committee on the suitability of the patient for surgery to the Mental Health Review Board for obtaining permission for surgery.

Mental health review board

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 under section 73 constitutes quasi-judicial Boards to be called the Mental Health Review Boards, for the purposes of this Act. The following procedure shall be followed by the Mental Health Review Board on receipt of application:

The Mental Health Review Board may ask for additional information and documents as necessary

The Mental Health Review Board may ask the psychiatrist to attend in person and give evidence to the Board

The Mental Health Review Board may examine the person on whom the psychosurgery is proposed to be performed and any other concerned person before arriving at its decision

As per section 80 sub-section (4) of the Act, the Board shall dispose of the application by granting or denying permission for psychosurgery within 90 days from the date of filing of the application.

The above regulations have been placed for psychosurgery under the Mental Health Care Act, 2017 and are effective from May 29, 2018.

Patient selection criteria

Diagnosis

At present, there is evidence for the efficacy of neurosurgical interventions in treatment-refractory OCD, MDD and TS. Due to the absence of level-I evidence and the availability of safer noninvasive alternatives, surgical treatments are recommended only for patients with chronic, severe and treatment-refractory illness. The screening inclusion and exclusion criteria should be done in line with the criteria used in the RCTs in the respective diseases. The presence of comorbid personality disorders and psychotic disorders are considered as relative contraindications due to lack of evidence. However, the suitability for surgery in the presence of these comorbidities can be decided on an individual case-to-case basis.

Patients should be assessed with a structured diagnostic interview to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for comorbidities. Detailed evaluation should be performed to establish treatment refractoriness, severity and chronicity of the disease. The suitability for surgery should be ratified by an independent review committee consisting of at least two psychiatrists (of which one should not be involved in the surgery), one neurologist and one neurosurgeon (not involved in the treatment of the patient). All evaluations should use a standardized rating scale and detailed drug and other treatment history.[46] It is imperative that all members of the team reach a uniform consensus and in case of disagreement, the further external opinion should be sought. In addition to clinical severity, patients should also be assessed with disability and quality of life scales. Surgery is recommended for people who show severe disability secondary to their illness (e.g., a Global Assessment of Functioning score of <45). Patients may be referred for preoperative neuropsychological evaluation and personality assessment to evaluate their baseline functioning.

Treatment refractoriness

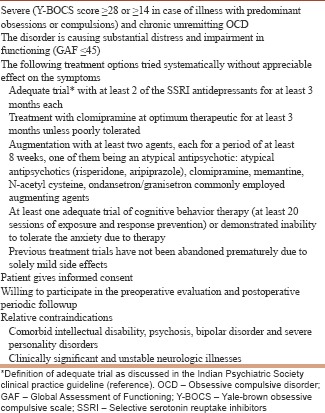

The definition of treatment refractoriness was actively debated in the meeting. The criteria for resistance to pharmacotherapy is generally well defined [Box 1], there was an engaging debate on the adequacy of the CBT trial. CBT has been found to be effective in controlled trials which have delivered a course of 15–20 sessions.[47] Hence, the consensus was that patients with OCD should be administered at least 20 sessions of CBT with OCD-specific treatment techniques. This can be provided at a tertiary care center or during in-patient admission as deemed appropriate. Patients who have consistently demonstrated the inability to undergo CBT due to difficulty in tolerating the anxiety associated with therapy may also be considered for surgery. Treatment response in prospective trials in OCD is generally defined as ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS score.[48] However, as structured assessment is often not available for the past trials in clinical practice, nonresponse can be defined based on clinical judgment of lack of meaningful improvement with a particular treatment.

Box 1.

Selection criteria for surgery for obsessive compulsive disorder, (adapted from clinical practice guidelines of the Indian Psychiatric Society)

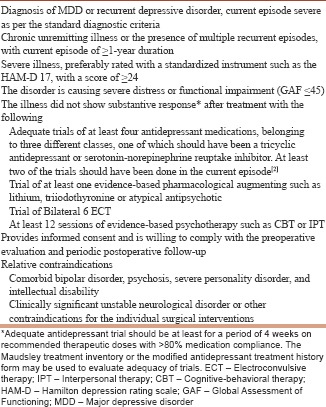

Most surgery trials on MDD have clearly specified criteria for assessing medication refractoriness [Box 2]. In addition to pharmacotherapy, there is a need to demonstrate refractoriness to other evidence-based noninvasive treatments. The illness should have been found to be nonresponsive to ECT, or there should be documented the inability to tolerate ECT due to adverse effects. Similarly, nonresponse to at least 12 sessions of evidence-based psychotherapy should be demonstrated. In a rare case where the patient explicitly refuses to undergo ECT, he/she can be offered surgery after establishing the capacity to provide informed consent. Treatment response in MDD is generally defined as ≥50% reduction from baseline score as assessed with standard depression rating scales such as MADRS or HDRS.[49] However, as such assessments are often not available in clinical practice for previous trials, nonresponse can be defined based on clinical judgment suggesting the lack of meaningful improvement with a particular treatment.

Box 2.

Selection criteria for surgery for major depressive disorder

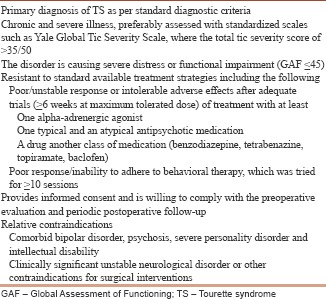

The consensus criteria for treatment refractoriness for OCD, MDD, and TS are described below [Box 1-3]. These are based on the standard criteria used in a various ethical committee approved research protocols and treatment guidelines. These may be revised as more experience is obtained in this field.

Box 3.

Selection criteria for surgery for Tourette syndrome

Surgical targets, expertise, and postoperative follow-up

The choice of the surgical target should be based on the available literature. If any new target is to be explored, an appropriate approval from the scientific and ethics committee should be obtained. Patient and their caretakers should also be briefed about the need and rationale to explore the new targets. Bart Nuttin, et al. notes that “Neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders (NPD)” should not be decided by, nor performed by, an individual in isolation and acting alone regardless of specialty. These procedures require an expert multidisciplinary team that includes trained stereotactic and functional neurosurgeons, working in a team with psychiatrists, neurologists, and neuropsychologists. The team should be specialized in the various target disorders and be able to provide comprehensive care.[50] Neurosurgeons should use modern, current standard techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized stereotactic planning software. It is a neurosurgeons’ important responsibility to check and maintain the accuracy and reliability of the stereotactic system.”[3] The group recommended that the neurosurgeon should be trained in functional neurosurgery and must have had few years of experience in regularly performing functional neurosurgery for movement disorders and has performed at least 50 movement disorders surgery functional neurosurgical procedures. The therapy should be performed in a multidisciplinary set up in a multispecialty hospital to ensure adequate preoperative and postoperative care. Post-operative imaging is mandatory (e.g., for documentation of the electrodeposition or place and extent of the lesion). The surgical treatment requires a high level of commitment and expertise. The group further maintains that the surgery should only be conducted where there is an oversight of ethics committee or Institutional Review Board, in line with the recommendations proposed by the National Commission, USA.[51] The group strongly emphasized the need for the postoperative follow-up and agreed with the Royal College of psychiatrists recommendation of a minimum 1-year follow-up.

Postoperative management

Immediate postoperative care and management should be done for the lesional surgeries and DBS as per standard norms. Postoperative care requires multidisciplinary input from psychiatrist, neurosurgeons, and other professionals as required such as psychologists and neurologists. The programming for DBS should be done in coordination with the psychiatrist, neurosurgeon and neurologist (if required), carefully monitoring for improvement, and adverse effects. For ablative surgery, a postoperative MRI may be required 3 months after the surgery to review the extant of the lesion. A postoperative neuropsychological and personality assessment may be performed after 6 months to evaluate for adverse effects. It should be remembered that surgery is not a standalone treatment, but is provided as a part of a package that consists of other treatments including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy as required. Patients should be educated beforehand that surgery may not be curative and other standard treatments have to be continued even after the surgery. It has also been reported that the addition of CBT may augment the effect of DBS even in people who have been refractory to CBT in the past.[19]

Informed consent

The consent process should be standardized and should be obtained by the neurosurgeon and the psychiatrist. The consent should include a full brief detailing the surgical procedure, its intended benefit, alternative treatments available and its complications. When a new surgical procedure is being attempted, more details should be supplemented such as the current evidence, worldwide experience with the procedure recommended, etc. The patient should offer their consent out of their own free will and be given adequate time to decide regarding the procedure. Although children and adolescents are generally excluded from surgery for OCD and MDD, DBS is sometimes considered in adolescents for TS when the disorder is extremely severe and dysfunctional.[52] In such cases, psychiatrists must demonstrate an awareness of the decision-making capacities of the adolescents and the need to balance their developing competencies and the role of families in medical decision-making. This includes adopting a developmentally appropriate approach to communicating with adolescents that is also respectful of their parents, family, and caregivers.[53] In cases where surgery is considered for adolescents, both informed consent from the adolescent and assent from the primary caregiver may be required. Surgery should be performed only after obtaining informed consent from the patient. There may be rare instances, where the patient is suffering from severe, treatment-refractory and highly disabling symptoms (such as self-injurious behavior) which may be amenable for treatment with neurosurgery, but the patient is incapable of providing informed consent. In such cases, surgery may be considered after obtaining consent from the primary caregiver and approval by an independent multidisciplinary clinical team as well as the Mental Health Review Board.

Capacity for informed consent

The group recognizes that informed consent is an important requisite for the surgery. Informed consent from a person with mental illness raises a question as to its validity in light of the illness. To overcome this difficulty the Sec 4 of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 mandates that Patients should undergo Mental Capacity assessment. This capacity assessment as per the Act has three important dimensions as follows:

To understand the information that is relevant to decide on the treatment (comprehension)

To appreciate any reasonably foreseeable consequence of a decision or lack of decision on the treatment (appreciations of benefits and risks)

To communicate the decision by means of speech, expression, gesture, or any other means

The assessment of mental capacity has to be done as per the guidance document prepared by the expert committee under section Sec 81 (1) and (2) of the Mental Healthcare Act 2017.

CONCLUSION

In this expert consensus statement, we provide an overview of the administration of neurosurgical procedures for psychiatric disorders in the Indian context. The available evidence supports the use of ablative surgery and DBS as an experimental treatment for patients with chronic severe and highly treatment-refractory OCD, MDD, and TS. Criteria have been suggested for judicious selection of appropriate candidates. It is imperative to obtain informed consent from the patient after explaining the evidence and expected outcome following the procedure. The current Mental Health Act, 2017 further requires the approval of the mental health review board before performing surgery. In line with worldwide practice, it would be necessary to obtain the opinion of independent clinicians (not directly involved in the concerned patient's treatment). The consensus statement is devised based on available literature on NPD, prevailing guidelines, and standard of practice, which have been modified for the Indian context. These guidelines will evolve as more data and information becomes available and should be reviewed with the most current literature.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the following collaborators who had attended, reviewed, and actively contributed to discussions leading to the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Mental Healthcare Act. 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 07]. Available from: http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Mental%20Health/Mental%20Healthcare%20Act,%202017.pdf .

- 2.Doshi PK. Anterior capsulotomy for refractory OCD: First case as per the core group guidelines. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:270–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuttin B, Wu H, Mayberg H, Hariz M, Gabriëls L, Galert T, et al. Consensus on guidelines for stereotactic neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:1003–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janardhan Reddy YC, Sundar AS, Narayanaswamy JC, Math SB. Clinical practice guidelines for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59:S74–90. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rück C, Karlsson A, Steele JD, Edman G, Meyerson BA, Ericson K, et al. Capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Long-term follow-up of 25 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:914–21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W, Li D, Sun F, Zhang X, Wang T, Zhan S, et al. Long-term follow-up study of MRI-guided bilateral anterior capsulotomy in patients with refractory anorexia nervosa. Neurosurgery. 2018;83:86–92. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepper J, Hariz M, Zrinzo L. Deep brain stimulation versus anterior capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:1028–37. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS132618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheth SA, Neal J, Tangherlini F, Mian MK, Gentil A, Cosgrove GR, et al. Limbic system surgery for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A prospective long-term follow-up of 64 patients. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:491–7. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.JNS12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung HH, Kim CH, Chang JH, Park YG, Chung SS, Chang JW, et al. Bilateral anterior cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: Long-term follow-up results. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2006;84:184–9. doi: 10.1159/000095031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, Gybels J, Meyerson B. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:1526. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg BD, Gabriels LA, Malone DA, Jr, Rezai AR, Friehs GM, Okun MS, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:64–79. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallet L, Polosan M, Jaafari N, Baup N, Welter ML, Fontaine D, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2121–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denys D, Mantione M, Figee M, van den Munckhof P, Koerselman F, Westenberg H, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1061–8. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huff W, Lenartz D, Schormann M, Lee SH, Kuhn J, Koulousakis A, et al. Unilateral deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: Outcomes after one year. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luyten L, Hendrickx S, Raymaekers S, Gabriëls L, Nuttin B. Electrical stimulation in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis alleviates severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1272–80. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman WK, Foote KD, Greenberg BD, Ricciuti N, Bauer R, Ward H, et al. Deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder: Pilot study using a blinded, staggered-onset design. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doshi PK. Expanding indications for deep brain stimulation. Neurol India. 2018;66:S102–12. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.226450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso P, Cuadras D, Gabriëls L, Denys D, Goodman W, Greenberg BD, et al. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome and predictors of response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantione M, Nieman DH, Figee M, Denys D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy augments the effects of deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3515–22. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luigjes J, de Kwaasteniet BP, de Koning PP, Oudijn MS, van den Munckhof P, Schuurman PR, et al. Surgery for psychiatric disorders. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:S31.e17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malone DA, Jr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Friehs GM, Eskandar EN, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lozano AM, Mayberg HS, Giacobbe P, Hamani C, Craddock RC, Kennedy SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, Taylor SF, Whitworth LA, McClintock S, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:839–49. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30371-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Howland RH, Bhati MT, O’Reardon JP, et al. A randomized sham-controlled trial of deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for chronic treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puigdemont D, Portella M, Pérez-Egea R, Molet J, Gironell A, de Diego-Adeliño J, et al. A randomized double-blind crossover trial of deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus in patients with treatment-resistant depression: A pilot study of relapse prevention. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40:224–31. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergfeld IO, Mantione M, Hoogendoorn ML, Ruhé HG, Notten P, van Laarhoven J, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule for treatment-resistant depression: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:456–64. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milev RV, Giacobbe P, Kennedy SH, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ, Downar J, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 4. Neurostimulation treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:561–75. doi: 10.1177/0706743716660033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christmas DMB, Eljamel MS, Butler S, Hazari H, Macuicar R, et al. Long term outcome of thermal anterior capsulotomy for chronic treatment refractory Depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, BMJ. 2010;82:594. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.217901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cosgrove GR, Rauch SL. Stereotactic cingulotomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:225–35. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(02)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, Jain FA, Cosgrove GR, Flaherty AW, et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eljamel MS. Ablative neurosurgery for mental disorders: Is there still a role in the 21st century? A personal perspective. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E4. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/25/7/E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, et al. The Yale global tic severity scale: Initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:566–73. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldermann JC, Schüller T, Huys D, Becker I, Timmermann L, Jessen F, et al. Deep brain stimulation for Tourette-syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2016;9:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ackermans L, Duits A, van der Linden C, Tijssen M, Schruers K, Temel Y, et al. Double-blind clinical trial of thalamic stimulation in patients with Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2011;134:832–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kefalopoulou Z, Zrinzo L, Jahanshahi M, Candelario J, Milabo C, Beigi M, et al. Bilateral globus pallidus stimulation for severe Tourette's syndrome: A double-blind, randomised crossover trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Servello D, Porta M, Sassi M, Brambilla A, Robertson MM. Deep brain stimulation in 18 patients with severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome refractory to treatment: The surgery and stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:136–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Ramirez D, Jimenez-Shahed J, Leckman JF, Porta M, Servello D, Meng FG, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome: The international Tourette syndrome deep brain stimulation public database and registry. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:353–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welter ML, Houeto JL, Thobois S, Bataille B, Guenot M, Worbe Y, et al. Anterior pallidal deep brain stimulation for Tourette's syndrome: A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:610–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrock LE, Mink JW, Woods DW, Porta M, Servello D, Visser-Vandewalle V, et al. Tourette syndrome deep brain stimulation: A review and updated recommendations. Mov Disord. 2015;30:448–71. doi: 10.1002/mds.26094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doshi PK, Ramdasi R, Thorve S. Deep brain stimulation of anteromedial globus pallidus internus for severe Tourette syndrome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:138–40. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_53_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dwarakanath S, Hegde A, Ketan J, Chandrajit P, Yadav R, Keshav K, et al. “I swear, I can’t stop it!” – A case of severe Tourette's syndrome treated with deep brain stimulation of anteromedial globus pallidus interna. Neurol India. 2017;65:99–102. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.198188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipsman N, Lam E, Volpini M, Sutandar K, Twose R, Giacobbe P, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate for treatment-refractory anorexia nervosa: 1 year follow-up of an open-label trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:285–94. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langevin JP, Koek RJ, Schwartz HN, Chen JWY, Sultzer DL, Mandelkern MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the basolateral amygdala for treatment-refractory posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:e82–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mink JW, Walkup J, Frey KA, Como P, Cath D, Delong MR, et al. Patient selection and assessment recommendations for deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1831–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Ledley DR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:621–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mataix-Cols D, Fernández de la Cruz L, Nordsletten AE, Lenhard F, Isomura K, Simpson HB, et al. Towards an international expert consensus for defining treatment response, remission, recovery and relapse in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:80–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peeters FP, Ruhe HG, Wichers M, Abidi L, Kaub K, van der Lande HJ, et al. The Dutch measure for quantification of treatment resistance in depression (DM-TRD): An extension of the Maudsley staging method. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlaepfer TE, George MS, Mayberg H WFSBP Task Force on Brain Stimulation. WFSBP guidelines on brain stimulation treatments in psychiatry. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11:2–18. doi: 10.3109/15622970903170835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research: Report and Recommendations: Psychosurgeries. Publication No. (OS) 77-0001. Washington, D.C: DHEW; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smeets AY, Duits AA, Horstkötter D, Verdellen C, de Wert G, Temel Y, et al. Ethics of deep brain stimulation in adolescent patients with refractory Tourette syndrome: A systematic review and two case discussions. Neuroethics. 2018;11:143–55. doi: 10.1007/s12152-018-9359-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Informed Consent to Treatment in Psychiatry. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 26]. Available from: https://www.cpa-apc.org/wp-content/uploads/Consent-2015-57-EN-FIN-web.pdf .