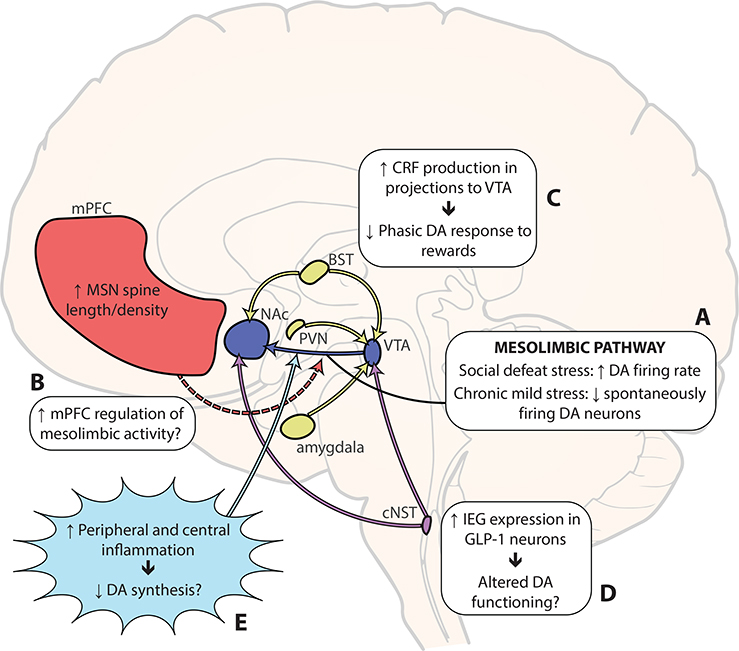

Figure 1, Key Figure. Putative circuit-level and molecular mechanisms of stressinduced anhedonia.

(A) In studies using social defeat stress in mice (applied over 10 days), an increase in the firing rate of VTA dopamine neurons was observed, but only in the “susceptible” group (those animals that developed anhedonic-like behaviors following stress) [26–28]. Chronic mild stress (4–7 weeks) decreased the number of spontaneously active VTA dopamine neurons [13,29,30]. (B) Some work suggests that increased mPFC excitability could suppress activity in the mesolimbic pathway [30,41]. (C) Endogenous CRF release in VTA seems to mediate the effect of restraint stress on motivation to work for food reward, likely by decreasing phasic dopamine responses to reward [64]. (D) GLP-1 signaling appears to mediate the hypophagic effects of restraint stress [77], likely by decreasing the rewarding value of food [82]. GLP-1 neurons in cNST project directly to VTA and NAc [83], where they appear to influence dopaminergic functioning, although the direction of the effect is unclear [85–88]. More research is needed to assess whether GLP-1 neurons (and other homeostatic energy systems) contribute to stress-induced anhedonia. (E) Inflammation may inhibit dopamine availability [100], either by inhibiting the function of enzymes in the dopamine biosynthetic pathway (see [93]) or by creating oxidative stress through increased kynurenine [106]. BST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; cNST, caudate nucleus of the solitary tract; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; DA, dopamine; GLP-1, glucagonlike peptide-1; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; MSN, medium spiny neuron; NAc, nucleus accumbens; PVN, hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.