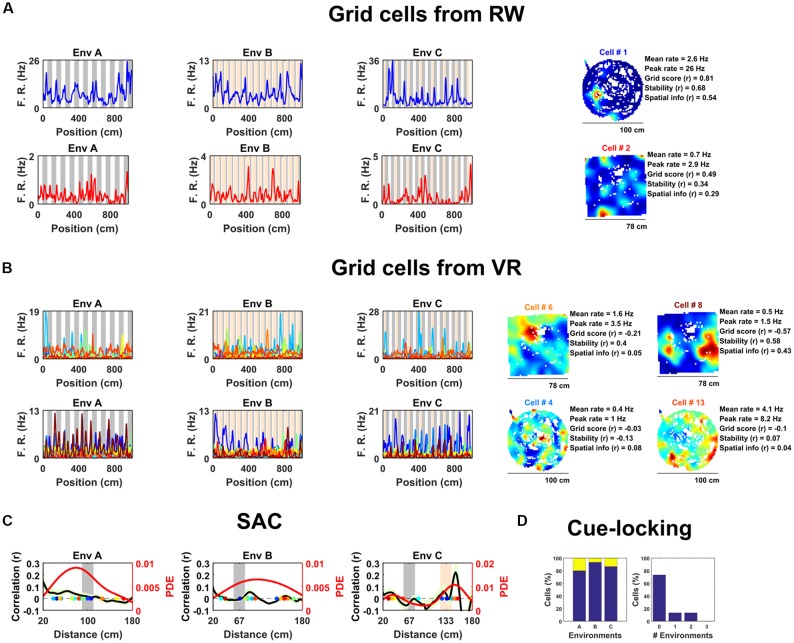

Figure 1.

Spatially periodic activity in real world (RW) and virtual reality (VR) environments, a subset of non-grid medial entorhinal (mEC) cells show cue-locking in VR environments. (A) Spatial activity from two example grid cells—identified based on RW recordings (right)—in each of the three VR environment (left). Repeating cues are indicated as colored bars in the background of the VR plots. Cells are color coded such that the title on RW ratemaps matches line color on the VR plots. (B) Similar to (A), spatial activity from two cells which were (incorrectly) classified as grids cells based on VR activity (left) but not based on RW open field activity (right). Despite the regularity of their firing patterns in VR, these cells showed no clear grid-like firing in RW and only limited spatial responses. (C) Cue-locking in grid cells (n = 15, identified from RW) was investigated using spatial auto-correlograms (SACs). Plots show mean (black line) ± SEM (light green shade area) SACs across cells (left y-axis). Note the lack of periodicity corresponding to the frequency of cues in the VR environments (indicated by gray and orange bands). The overlaid color-coded dots represent the dominant spatial frequency in the 20–180 cm range detected from the SAC of each grid cell—the distribution of these points is indicated by the red line (right y-axis). (D) Proportion of grid cells exhibiting cue-locking (yellow) and no cue-locking (blue) in each VR environment (left) and proportion showing cue-locking in multiple VR environments (right).