Abstract

Spontaneous regression of a primary testicular germ-cell tumour (GCT), over time known as ‘Burned out’, ‘Shrinking Seminoma’, ‘pT0’, ‘Burnout’ or ‘Spontaneous Regression’, is an uncommon, generally metastatic phenomenon, which may present elevated tumour markers and a suspicious testicular ultrasound image. The histological study of the testicle demonstrated morphological changes of complete or partial tumour regression and found fibrous scarring and other characteristic changes of this phenomenon, which in some cases include vestiges of GCT.

There are few publications on testicular GCT tumour regression and those that exist present limited data on the biology of the disease and its etiopathogenesis. This entity was recently recognised in the latest edition of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Classification of Tumours.

We present our clinical, imaging, laboratory, cytohistological and management experience, as well as a historical review of the literature.

Keywords: testicle, spontaneous regression, burned out, germ-cell tumour

Introduction

Spontaneous tumour regression has been reported in various neoplasias [1, 2]. In testicular cancer, it is defined as a germ-cell tumour (GCT) that has completely or partially regressed, without any intervention, leaving a scar in the parenchyma with or without vestiges of GCT [3]. The etiopathogenesis of the regression is not defined and it is thought that less than 5% of all testicular GCTs undergo spontaneous regression [4]. It usually presents as metastatic disease and is manifested by symptoms secondary to it. It may have high tumour markers, depending on the histological lineage. Historically, many cases have been classified as primary extragonadal GCTs (EGCTs) but most subsequent studies found evidence of regression of a primary testicular [5–24].

We present our experience and carry out a historical review of the literature.

Materials and methods

Sample

Clinical records of patients from the Urology Service of the Regional Institute of Neoplastic Diseases North, in Trujillo, Peru, were reviewed, from January 2010 to June 2018. We identified the cases with a diagnosis of testicular GCT regression and proceeded to collect the data in a digital card developed for this purpose.

Epidemiological and clinical study

We obtained data such as age, pathological history, time of illness, signs, symptoms and information from the physical examinations.

Imaging study and clinical laboratory

Imaging information obtained was confirmed by evaluating existing material in the Radiology services’ records (ultrasound, x-rays, CT scans and others). Tumour marker data such as alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) were collected and correlated with the histological findings.

Management, evolution and current status of the disease

We collected data regarding the type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other), as far as primary, metastasis and/or recurrence.

Cytological and anatomopathological material

Of the testicle.

Of the metastasis.

We reviewed the cytological and histological material, classifying it according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) 2016 classification of testicular tumours and paratesticular tissue. This edition recognises GCT regression as an entity [4].

Staging

We used the 8th Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system based on the study of tumour (T), lymph node involvement (N), the presence of metastasis (M) and serum tumour marker (S) [25].

Current state of the disease

Upon reviewing the medical history, we obtained the dates of the last check-up and the state of the disease. In the cases with no recent data, we located patients.

Review of existing literature

Bibliographic searches were conducted on Scopus, Medline, EBSCO and BVS from 2000 to the present. The data obtained were analysed, compared and discussed.

Results

Sample

In the review of the medical records, five [5] cases were identified with a diagnosis of primary testicular GCT regression, all metastatic with complete regression.

Case Report

Case 1

A 54-year-old patient without any significant history, with a 6-month disease time, characterised by weight loss, abdominal tumour and lumbar and abdominal pain. Upon physical examination, no peripheral adenopathies were found, a hard fixed mass was felt in the abdomen located in the mesogastrium and testicles with no notable particularities. On the CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (CT-CAP), a retroperitoneal 17 cm × 10 cm × 8 cm tumour was observed. It encompassed the abdominal aorta, collapsed the vena cava and projected to the iliac arteries; it was initially classified as lymphoma. A core percutaneous biopsy was performed and had inconclusive pathological results. As part of imaging studies, a scrotal ultrasound was requested and a 23 mm × 26 mm hypoechogenic nodule was found in the right testicle. The AFP and HCG tumour markers were found in normal parameters and the LDH in 2480UI. Radical orchiectomy was performed and fibrous scarring associated with histological changes of regression was found. He underwent exploratory laparotomy and subtotal resection of the retroperitoneal tumour with a cytological, histological and immunohistochemical study consistent with a seminoma-type GCT. He received chemotherapy (chemo) with complete tumour remission and tumour markers within normal values; during treatment, he developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in both lower extremities (LEs), which was managed medically. At the 60-month follow-up, he shows no evidence of disease.

Case 2

A 58-year-old patient with a 2-month disease time, characterised by bilateral lumbar pain, sensation of thermal rise, volume increase in LEs and weight loss. Physical examination revealed a left supraclavicular lymph node conglomerate of hard consistency, a mass in mesogastrium, hard edema in both legs and no other peripheral adenopathies. The abdomen and testicles were without any particular features. Supraclavicular, subclavian, mediastinal and retroperitoneal adenopathies were observed via CT-CAP, the latter being in a 15 cm × 13 cm × 9 cm conglomerate, which includes the great vessels, as well as thrombus in vena cava and iliac vessel. It was also initially classified as lymphoma. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the supraclavicular adenopathy was performed, revealing cytological features of a malignant round-cell neoplasm, likely seminoma. The scrotal ultrasound showed the right testicle with microcalcifications and an 8 mm × 7 mm hypoechogenic nodule. Tumour markers were AFP 4.5UI/l, HCG 8.02UI/L and LDH 3637UI/L. A radical orchiectomy was performed, with a histological report of the fibrous nodule and regression changes, among them germinal neoplasia in situ. A supraclavicular tumour biopsy was performed with histological and immunohistochemical study consistent with seminoma-type GCT. The patient received chemo with complete tumour remission at the supraclavicular and mediastinal level; the remission was partial in the retroperitoneum, therefore, a positron emission tomography was performed, reporting para-aortic tissue of 35 mm, inactive residual appearance, which diminished in subsequent tests. At the 42-month follow-up, there is no evidence of active disease.

Case 3

A 23-year-old patient with a history of thoracic trauma and haemoptysis underwent a thoracic tomography, in which multiple nodules were observed in both pulmonary fields. Subsequently, he developed hemiplegia on the left; in the supplemental CT, a 48-mm hypodense image in the brain was found in the right fronto-parietal region; also in the retroperitoneum, a 11cm × 7 cm × 4cm ganglion conglomerate. Physical examination revealed no peripheral adenopathies, resistance to palpation in the abdomen at the level of mesogastrium and testicles without particular features. The scrotal ultrasound revealed a left testicle with multiple microcalcifications and a 9 mm × 8 mm heterogeneous, hypoechogenic nodule. The tumour markers were AFP 0.9UI/L, HCG 19609UI/L and LDH 561UI/L. Radical orchiectomy was performed with pathology that showed the testicle with fibrous scar associated with histological regression changes. The patient underwent a pulmonary nodule FNA with cytological study compatible with choriocarcinoma-type GCT. Due to brain metastasis, he received radiotherapy (RT) and started chemo. During the treatment, he presented seizures, anaemia and febrile neutropenia; the poor clinical response was observed in imaging studies (hepatic metastasis, increased dimensions of brain metastasis with perilesional haemorrhage) and in the tumour markers (AFP 3.73UI/L, HCG 214UI/L and LDH 734UI/L). Chemo was not completed due to complications and the patient died 7 months after the initial diagnosis with the evidence of disease progression.

Case 4

A 36-year-old patient with no relevant history, with a 7-month disease time characterised by left lumbar pain, abdominal mass, weight loss and increase in volume of the left leg. Upon physical examination, no peripheral adenopathies were found. In the abdomen, a hard and fixed mass was felt in the mesogastrium, testicles had no particularities and an increase in volume in the left leg. On the CT-TAP, a retroperitoneal tumour of 16 cm × 9 cm × 9 cm was observed, which includes the aorta and the cava. Doppler ultrasonography reported DVT in the iliac, femoral and popliteal veins of the left leg. On the scrotal ultrasound, a 30-mm hypoechoic nodule was found in the left testicle, associated with multiple microcalcifications. The tumour markers were AFP 0.69UI, HCG 0.44UI and LDH 1240UI. Radical orchiectomy was performed with pathology that reported parenchyma with a fibrous scar and tubular hyalinization. Percutaneous biopsy of the retroperitoneal tumour with histological and immunohistochemical exam was compatible with the seminoma-type GCT. Full chemo with partial remission of the disease and tumour markers were within normal parameters. The residual tissue has progressively decreased in volume. Currently, at 20 months of follow-up, there is no evidence of active disease.

Case 5

A 20-year-old patient without any significant history, with a 6-month disease time, characterised by weight loss, abdominal tumour and pain. Upon physical examination, no peripheral adenopathies were found, a hard fixed mass was felt in the abdomen located in the mesogastrium, testicles had no notable particularities. On the chest, abdomen and pelvis CT, a retroperitoneal tumour was observed predominantly in the left iliac region measuring 16 cm × 15 cm × 9 cm, which includes iliac vessels and left renal agenesis. Suspecting a metastatic GCT, a scrotal ultrasound was performed and found a 5 mm × 10 mm isoechogenic nodule in the left testicle. Tumour markers were 1745UI AFP, HCG 3705UI and LDH 2948UI. Radical orchiectomy was performed and fibrous scarring associated with histological changes of regression was found. A percutaneous biopsy of the retroperitoneal tumour was performed, with a cytological and histological report of mixed GCT (embryonal carcinoma, teratoma and yolk sac tumour). During the evolution of the disease, one of the complications presented was a bowel obstruction, resolved with sigmoidectomy and block retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Patient was currently in chemo with partial remission.

Epidemiological and clinical study

The cases presented between 20 and 58 years with an average age of 38 years. No significant data were found with regard to history. The average disease duration was 3.8 months (range 1–7 months), mainly characterised by abdominal and/or lumbar pain, weight loss and abdominal tumour in three cases and one supraclavicular tumour. On examination of testes, tumours were not felt on palpation in any patient. In two cases, the initial diagnosis was lymphoma Table 1.

Table 1. Epidemiological and clinical data.

| Case | Age (years) | Pathological history | Disease time | Principal signs and symptoms | Testicular examination | Admission Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 54 | No | 6 months | Abd. tumour, lumbar and abdominal pain, WL. | Negative | Lymphoma |

| 2. | 58 | No | 2 months | Sc. and abd. tumour, lumbar pain, inc. vol. LEs, WL. | Negative | Lymphoma |

| 3. | 23 | No | 1 month | Haemoptysis and left WL hemiplegia | Negative | EAD Pulmonary Mets. |

| 4. | 36 | No | 7 months | Abd. tumour, lumbar pain, WL., incr. left LE vol. | Negative | Metastatic GCT |

| 5. | 20 | No | 3 months | Abd. tumour, abd. pain | Negative | Metastatic GCT |

WL. Weight loss; Abd.: abdominal; SC: supraclavicular; LEs Incr. Vol.: enlargement of limbs; Mets: metastasis; EAD: aetiology to be determined.

Imaging and laboratory study

The results of the imaging studies conducted are summarised in Table 2. All five cases were metastatic, with retroperitoneal tumours larger than 10 cm; in four cases, the tumour encompassed the aorta, cava and/or iliac Figure 1. Two had a diagnosis of DVT. As to tumour markers, in all cases, the LDH was high and, in the other two, HCG and AFP.

Table 2: Imaging and tumour marker data at the initial diagnosis.

| Testicular ultrasound | CT abdomen/pelvis | CT thorax/brain | Doppler ultrasound vessels | Tumour markers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP (UI) | HCG (UI) | LDH (UI) | |||||

| 1. | RT with 23 mm× 26 mm × 12 mm. hypoec. nodule. | 17 cm × 10 cm × 8 cm. RTP Tumour, encompasses aorta and collapses cava | No metastasis | No DVT | Normal | Normal | 2480 |

| 2. | RT with 8 mm × 7 mm hypoec. nodule. | 15 cm × 13 cm × 9 cm. RTP Tumour, encompasses the large vessels | Supraclavicular and mediastinal adenopathies | Cava and iliac DVT. | Normal | Normal | 3637 |

| 3. | LT with 9 mm × 8 mm hypoec. pseudonodule | 11 cm × 7 cm × 4 cm. RTP Tumour, encompasses aorta and iliac | Multiple pulmonary and frontoparietal Mets. | No DVT | Normal | 19209 | 561 |

| 4. | LT with 30 mm. hypoec. node. | 16 cm × 9 cm × 9cm RTP Tumour, encompasses large vessels | No metastasis | Iliac and left femoral DVT. |

Normal | Normal | 2480 |

| 5. | LT with 5 mm × 10 mm isoec nodule. | 16 cm × 15 cm × 9 cm. RTP tumour in the left iliac region, encompasses vessels | No metastasis | No DVT | 1745 | 3705 | 2948 |

RT: right testicle; LT: left testicle; hypoec.: hypoechogenic; RTP: retroperitoneal; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; Mets.: metastasis.

Figure 1. Imaging studies: (A) Ultrasound showing heterogeneous nodule and microcalcifications in the testicular parenchyma. (B) Tomography with retroperitoneal mass that encompasses large vessels.

Management, evolution and current status of the disease

The initial clinical suspicion in the first three cases was different from primary testicular metastatic GCT, therefore, the diagnostic work-up included aspiration and/or surgical biopsies of retroperitoneal, supraclavicular and lung masses, respectively. Laboratory studies and images were supplemented with histological findings and radical orchiectomy was performed. In the last two cases, where GCT was suggested from the beginning, the pathology of the orchiectomy was consistent with tumour regression, having found evidence of germinal neoplasia in the study of the metastasis.

With the anatomopathological diagnosis of testicular tumour regression and metastatic staging, all patients received chemo and had favourable responses corroborated through imaging studies and MT, except for the third case, who also received RT due to brain metastasis and progressed to death (Table 3).

Table 3. Data on the management, anatomopathological diagnosis and state of the disease.

| Initial surgical management | AP (1) | Second procedure | AP(2) | Adjuvant Therapy | Time of follow-up | Status disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | RTP tumour biopsy | Seminoma | Radical Orchiectomy | Fibrous scar | Chemo (BEP x 4) | 53 months | NED |

| 2. | Supraclavicular tumour biopsy | Seminoma | Radical Orchiectomy | Fibrous scar | Chemo (BEP x 4) | 40 months | NED |

| 3. | Pulmonary nodule biopsy | Choriocarcinoma | Radical Orchiectomy | Fibrous scar | Chemo + WBRT | 7 months | DOD |

| 4. | Radical Orchiectomy | Fibrous scar | RTP tumour biopsy | Seminoma | Chemo (BEP x 4) | 16 months | NED |

| 5. | Radical Orchiectomy | Fibrous scar | RTP tumour biopsy | Mixed (EC/YST/T) | Chemo (BEP x 4) | 3 months | AWD |

EC: embryonal carcinoma; YST: yolk sac tumour; T: teratoma; WBRT: whole brain radiotherapy; BEP: bleomycin/etoposide/platinum; NED: no evidence of disease; DOD: dead of disease; AWD: alive with disease; AP: anatomical pathology.

Anatomopathological material

The existing material was reviewed and classified according to WHO classification of testicular tumours and paratesticular tissue (4).

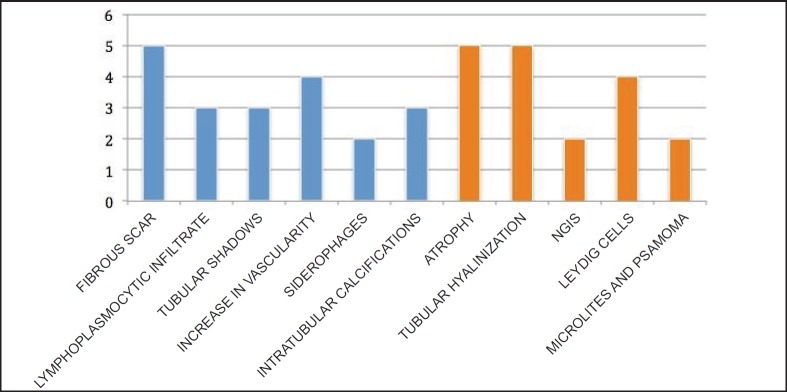

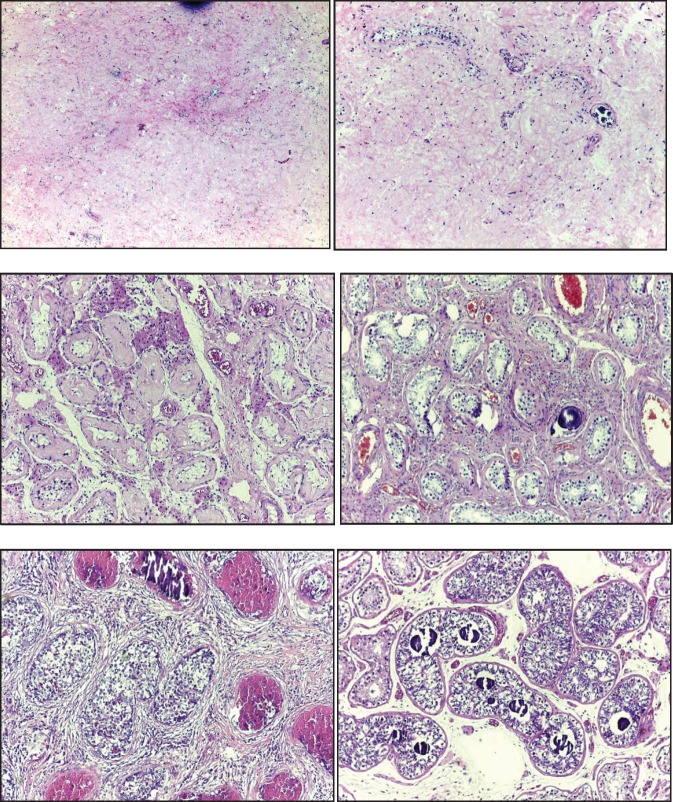

In the testicle product of radical orchiectomy, macroscopically, all cases presented a whitish fibrous scar, located close to the to rete testis. The surrounding testicular parenchyma did not present significant alterations. For histological interpretation, we divide the testicles into two regions: the scar and the area adjacent to the scar (paracicatricial), whose characteristics are described in Figure 2 and shown in micrographs in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Histomorphological characteristics of testicular tumour regression: scar (blue) and paracicatricial area (orange). The case numbers are on the ‘Y’ axis.

Figure 3. Microphotographs of the histomorphological characteristics of the testicular tumour regression: (A) Fibrous scar with increased vascularity. (B) Increase in vascularity and microcalcifications. (C) Tubular hyalinosis and presence of Leydig cells. (D) Microliths in paracicatric area. (E) NGIS-type embryonal carcinoma. (F) NGIS and intratubular calcifications.

With regard to metastasis, four of these were evaluated initially with cytology, two with FNAB and two with intraoperative cytology. The results of these showed germ-tumour cytology, allowing identification of the types seminoma, choriocarcinoma and embryonal carcinoma. Subsequently, all cases were subjected to conventional histological and immunohistochemical study, corroborating diagnoses of germinal neoplasia; the latter presented teratoma and yolk sac tumour in addition to embryonal carcinoma. Table 4 presents the anatomopathological results in correlation with the tumour markers.

Table 4. Anatomopathological results of the metastasis, diagnostic procedure and correlation with tumour markers.

| Anatomopathological diagnosis | Diagnostic procedures | Altered tumour markers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | GCT (Seminoma) | IOC-SBx of RTP tumour | LDH |

| 2. | GCT (Seminoma) | FNAB-SBx of supraclavicular tumour | LDH |

| 3. | GCT (Choriocarcinoma) | FNAB of lung tumour | HCG; LDH |

| 4. | GCT (Seminoma) | RTP tumour biopsy | LDH |

| 5. | Mixed GCT (EC/YST/T) | IOC-SBx of RTP tumour | HCG; AFP; LDH |

IOC: Intraoperative cytology; SBx: Surgical biopsy; RTP: retroperitoneum; FNAB: Fine needle aspiration biopsy; EC: embryonal carcinoma; YST: yolk sac tumour; T: teratoma.

Staging

The five cases were classified as metastatic stage pT0, with findings of testicular tumour regression.

Literature review

Performing a search from January 2000 to June 2018, 159 cases were found in 57 articles. The cases arose between 17 and 67 years old with an average age of 35.96 years; only in nine cases (15.8%), cryptorchidism was reported as a precedent. 96.8% of the patients had metastatic disease and 71.7% had complete regression.

Likewise, the time frame of the review found that there is a discrete increased frequency of regression in the right testicle (47%) and the more common histological type is seminoma (50.8%). The publications by author’s locations were as follows: Europe 22 (38.6%), Asia 18 (31.6%) and America 17 (29.8%). The summary of the data is presented in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5. General data from the 2000–2018 literature review.

| 1. Total Publications | 57 | |

| 2. Total Cases | 159 | |

| 3. Average age/range (years) | 35.96 | 17 - 67 |

| 4. Pathological history: | ||

| - Cryptorchidism | 9 | (15.8%) |

| - Contralateral GCT | 2 | (3.5%) |

| 5. GCT burned out: | ||

| - Metastatic | 154 | (96.8%) |

| - Non-metastatic | 5 | (3.2%) |

| 6. Testicular tumour regression: | ||

| - Complete | 114 | (71.7%) |

| - Partial | 45 | (28.3%) |

| 7. Affected testicle: | ||

| - Right | 74 | (47%) |

| - Left | 67 | (42%) |

| - Undetermined | 18 | (11%) |

| 8. Histological type of GCT: | In metastasis | In the testicle |

| - Pure seminoma | 81 (50.8%) | 23 (53.5%) |

| - Mixed with seminoma | 12 (7.4%) | 8 (18.7%) |

| - Mixed without seminoma | 17 (11.1%) | 3 (6.9%) |

| - Pure embryonal carcinoma | 16 (10.1%) | 2 (4.6%) |

| - Pure Choriocarcinoma | 4 (2.5%) | 0 |

| - Pure yolk sac tumour | 4 (2.5%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| -Teratoma | 5 (3.1%) | 6 (14%) |

| - Undetermined | 20 (12.5%) | NA |

| - Total | 159 (100%) | 43 (100%) |

Table 6. Publications on spontaneous testicular GCT regression (2000–2018).

| No. | Author (Year)/bibliographic Ref. No. | No. cases | Age/Average (years) | GCT | 6. Testicular tumour regression: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic | No metastatic | Complete | Partial | ||||

| 1 | Leleu et al (2000) [44] | 1 | 34 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | Naseem et al (2000) [36] | 2 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Scholz et al (2001) [7] | 26 | 36 | 26 | 22 | 4 | |

| 4 | Kebapci et al (2002) [72] | 1 | 22 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5 | Bissen et al (2003) [39] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 | Tasu et al (2003) [59] | 5 | 31 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| 7 | Fabre et al (2004) [26] | 5 | 34.6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 8 | Mola et al (2005) [69] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 9 | Perimenis et al (2005) [45] | 1 | 40 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 10 | Castillo et al (2005) [68] | 1 | 25 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 11 | Curigliano et al (2006) [46] | 1 | 42 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12 | Balzer and Ulbright (2006) [3] | 42 | 32 | 42 | 26 | 16 | |

| 13 | Yamamoto et al (2007) [10] | 1 | 39 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 14 | Parada et al (2007) [64] | 2 | 19.5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 15 | Patel and Patel (2007) [53] | 1 | 23 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 16 | Vasquez et al (2008) [56] | 3 | 38 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 17 | Coulier et al (2008) [11] | 1 | 53 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 18 | Angulo et al (2009) [38] | 17 | 31 | 17 | 10 | 7 | |

| 19 | Kontos et al (2009) [40] | 1 | 31 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 20 | Ha et al (2009) [47] | 1 | 23 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 21 | Yucel et al (2009) [48] | 1 | 28 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 22 | Yucel et al (2009) [49] | 1 | 49 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 23 | Mesa et al (2009) [12] | 1 | 55 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 24 | Orlich and Jimenez (2010) [50] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25 | Gaytán et al (2010) [51] | 1 | 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 26 | Jaber S. (2010) [52] | 1 | 32 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 27 | Womeldorph et al (2010) [73] | 1 | 55 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 28 | Musser et al (2010) [13] | 1 | 63 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 29 | Herrera et al (2011) [14] | 4 | 33 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| 30 | Balalaa et al (2011) [57] | 1 | 31 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 31 | Kar et al (2011) [15] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 32 | Preda et al (2011) [70] | 1 | 43 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 33 | Gonzales et al (2012) [16] | 1 | 35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 34 | Peroux et al (2013) [60] | 1 | 18 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 35 | Gurioli et al (2013) [58] | 2 | 42.5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 36 | Sahoo et al (2013) [41] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 37 | Ichiyanagi et al (2013) [43] | 1 | 47 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 38 | Miacola et al (2014) [42] | 1 | 36 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 39 | Chung et al (2014) [54] | 1 | 33 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 40 | Onishi et al (2013) [18] | 1 | 41 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 41 | Qureshi et al (2014) [71] | 1 | 20 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 42 | Budak et al (2015) [55] | 1 | 39 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 43 | McCarthy et al (2015) [63] | 1 | 24 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 44 | Gomis et al (2015) [74] | 1 | 42 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 45 | Nguyen et al (2015) [62] | 1 | 64 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 46 | Hu et al (2015) [75] | 1 | 37 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 47 | George et al (2015) [19] | 1 | 24 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 48 | Ishikawa et al (2016) [21] | 1 | 42 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 49 | El sanharawi et al (2016) [61] | 5 | 37 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 50 | Iwatsuki et al (2016) [76] | 1 | 29 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 51 | Nakazaki. et al (2016) [65] | 1 | 54 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 52 | El-sharkawy and Al-Jibali (2017) [78] | 1 | 22 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 53 | Juul and Rasmussen (2017) [22] | 1 | 57 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 54 | Mosillo et al (2017) [28] | 1 | 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 55 | Nishisho et al (2017) [23] | 1 | 30 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 56 | Ulloa-Ortiz et al (2017) [77] | 1 | 52 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 57 | Freifeld et al (2018) [24] | 1 | 44 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 159 | 35.9 | 154 | 5 | 114 | 45 | ||

In the review conducted, there are some publications of cases reported as ‘burned out’, the same as the clinic and/or imaging studies and/or laboratory are compatible with GCT; however, they were not considered because they do not have complete data, especially histological findings of the testicle.

Discussion

Over time, the ‘phenomenon’ of tumour regression has been described in different pathologies such as melanoma, breast cancer, lymphoma, renal carcinoma, among others [1, 2]. It is currently known that the process that keeps tumours alive does not only depend on their ability to multiply and block apoptosis, but there is also a close relationship with the immune environment in which the tumour develops, the so-called tumour microenvironment [4, 26–28].

There are not many publications on the regression of testicular GCTs; this entity has only recently been recognised in the last edition of the WHO’s book on Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs (2016), in the chapter on testicular tumours and paratesticular tissues [4]. It is considered that the first to describe this phenomenon was Prim in 1927; he reported the case of a 51-year-old patient who died with multivisceral and retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis, with ‘chorionephiteliomatösen’ histology and no known primary. At the autopsy, he found a scar on the right testicle and posed the question of whether it may have been the primary one and presented ‘spontaneous healing’ [29]. In 1954, Rather et al [30] reported six new cases and reviewed the bibliography, finding 18 additional cases. In the final histological analysis, they described testicles as seven having only one scar, nine having germ-cell tumours and eight having fibrosis, tubular and cystic structures, hemosiderin deposits and calcification. The characteristics of testicular tumour regression have been defined this way for over six decades, with a high approximation for existing approaches, same as have been identified in our sequence.

In 1955, Slater et al [31] reported a case where a patient with a retroperitoneal mass with ‘seminoma and chorioepithelioma’ histology. He underwent bilateral orchiectomy and a small, solid nodule in the left testicle was found, which the microscope identified as scarred teratoma, confirming that they were dealing with a ‘burned out primary…’. This is likely the first publication to use this terminology to define tumour regression in germ cells.

In 1961, Azzopardi et al [32] published a series of 17 cases of young patients that passed away due to disseminated metastatic illnesses, eight with choriocarcinoma histology, five with embryonal carcinoma and four mixed. All of the testicle exams were normal but the pathology study found fibrous scarring in the majority of cases with haemotoxylin deposits in the seminiferous tubules, consistent with the burnt out phenomenon. In 1965, in a second publication on the subject, the same author presented a case that illustrated the pattern of regression in a testicular seminoma with viable metastasis. The author provides a comprehensive description of typical histological findings, as well as a comparison with choriocarcinoma [33].

In 1970, Veragut et al [34] reported two cases of young patients with a diagnosis of retroperitoneal seminoma with no evidence of a primary. In their discussion, they describe the ‘necrobiosis phenomenon’ as a means to explain the spontaneous involution of testicular tumours, indicating that it occurs more frequently in choriocarcinoma and is rare in seminoma.

In 1990 and 2000, two works were published, titled ‘Shrinking Seminoma’ and ‘Shrinking Seminoma—Fact or Fiction?’, describing volume reduction in the testicle with seminoma, where the mechanism is fundamentally ischemia—necrosis secondary to intermittent testicular torsion. Other possible causes also described were chronic inflammation and hormonal disorder. In the aforementioned phenomenon, depending on the stage at which it is diagnosed, a testicle ‘shrunken’ in size, with or without a residual tumour may be found, which is why in a patient with a retroperitoneal, mediastinal or other mass that also presents testicular shrinking, a GCT should be suspected [35, 36].

Near the end of the 20th century, various publications report on probable EGCT, in which lesions were found at the testicular level, consistent with spontaneous regression, correlating to the primary [5–9]. According to different publications, 90% of EGCTs occur between ages 20 and 35 and represent less than 5% of total GCTs; most commonly found in the anterior mediastinum, followed by the retroperitoneum and rarely in the pineal gland, presacral region or in another organ [7, 17, 20, 37, 38]. In general, every extragonadal tumour with GCT histology is considered a metastasis of hidden gonadal GCT until proven otherwise, with some authors even questioning the existence of EGCT [7].

Although the mechanism behind primary tumour regression has not been determined, there are several hypotheses. The two main hypotheses are: those related to an immunological response mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes that recognise tumour antigens and destroy malignant neoplastic cells, with subsequent fibrosis replacement; and those related to an ischemic response in the neoplasia, secondary to the blood supply deficit due to high metabolic rates and/or intermittent testicular torsion (Shrinking Seminoma). Another hypothesis indicates that when seminomas become metastatic, the organism produces antibodies that attack the metastasis, as well as the primary testicular tumour, which shrinks and may even be destroyed, leaving only traces. This foundation refers to the immunological theory of regression [26, 39–43].

Clinical manifestations generally depend on the metastatic disease [44–52]; only a few non-metastatic cases were diagnosed with signs and local symptoms such as pain in the scrotal sack, testicular shrinking and infertility studies. [26, 36, 43, 53, 54]. In accordance with the histology review performed, the most frequent symptoms were lumbar, abdominal and abdominal mass pain, very similar to the findings in our series, in addition to reports of weight loss. During the clinical evaluation of our case series, the first two patients were initially listed as having the lymphoproliferative syndrome and the third as having pulmonary metastasis of unknown origin. In various revised reports, due to various symptoms, the diagnostic work was also directed to pathology different from that of GCT [10–12, 14, 21, 24, 44, 54–57].

Examination of the scrotal sacs through palpation is insufficient to exclude testicular tumours. The findings depend on the size of the tumour, its relation to the size of the testicle, the placement, consistency and/or associated pathologies, such as hydrocele, cysts or others [7, 26, 28, 56, 58]. In our casuistry, the physical exam found no testicular tumours, supplemented with ultrasound.

The sensitivity of the testicular ultrasound for diagnosing GCT is close to 100%, so all young patients with a retroperitoneal or mediastinal mass should undergo this test. The characteristics of testicular tumour regression are not specific, as there have been findings of hyperechogenic, hypoechogenic and mixed lesions, nodular and linear areas, signs of testicular atrophy and/or acoustic shadowing reflecting calcifications or fibrosis [3, 26, 59, 60]. If the ultrasound results are inconclusive, scrotal magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI) can be useful in better defining these findings that are not necessarily malignant (infarction, ischemia, trauma or infection) [43, 59, 61]. Patel and Patel [53] reported that, when using the sMRI, a finding that suggests neoplasia is the appearance of a rapid higher height peak at the lesion. In the collection of histological data, it was found that the ultrasound findings most frequently related to regression were hypo- and hyperechogenic lesions and microlithiasis. Another useful imaging test for metastatic lesion detection that is also essentially in the control and follow-up after chemotherapy is positron emission tomography, along with multislice tomography (PET/CT) through radiopharmaceutical administration of F18-FDG [24, 28, 37, 62].

Tumour markers are fundamental to the diagnostic approach, staging, treatment and follow-up; they show up in varying forms depending on the histological lineage and the response to treatment. In our report, during the initial diagnostic, LDH was increased in all of the cases in relation to the metastasis and tumour burden, in two patients with HCG and in one with AFP [4, 5, 25, 38, 60].

The five reported cases were metastatic and diagnosed using the cytohistological results of the lesions, which, in addition to the clinical findings, laboratory and imaging studies, allowed us to formulate the primary testicular diagnosis and to indicate the corresponding radical orchiectomy. In the various reports, the macroscopic description of the testicles showing the partial or total tumour regression phenomenon, the presence of lesions that are hardened, whitened, fibrose, of scar aspect, in the form of nodules (singular or multiple), banded, linear or starred, is reported [3, 4, 7, 38, 63–65]. We found fibrosis scarring in every one of our cases.

Microscopically, our findings coincide with the WHO description defining the diagnostic criteria for testicular tumour regression, including inflammatory lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (present in around 90% of cases), tubular hyalinization (around 70%), increase in vascularity (50%), hemosiderin (44%) and thick intratubular calcifications. The peripheral area was observed to have atrophy and sclerosis of the seminiferous tubules (100%), germinal cell malignancy in situ (approximately 50%), hyperplasia in Leydig cells (45%), intratubular microlitres (30%). The literature mentions intertubular calcifications and germinal neoplasia in situ as pathognomonic signs [3, 4, 38].

It is known that all germinal tumours have the potential for regression; however, there is evidence in the literature that disagrees on the frequency of the histological subtypes that demonstrate this phenomenon. Historically, choriocarcinoma has been considered the most prone to regression, but recent reports, as well as ours, confirm that seminoma has the most common histology, with exception of the spermatocytic type, which is now a separate entity. The teratomas are classified as the histology group with the lowest probability of regression [3, 4, 8, 38, 66, 67].

Various publications agree that chemotherapy is not completely effective for the testicles due to the haemato-testicular barrier and thus the necessity of surgical resection (orchiectomy) on the ‘regressed’ primary is essential and represents the cornerstone of the burned out definition, in addition to being the foundation for proper treatment. The management is, in general, similar to that for primary GCT testicles [6, 7, 56, 58, 59, 68–71].

For a large majority of patients, the diagnostic work was performed based on the symptomatology of the metastasis, not infrequently with an approach different to that of burned out GCT that shows the delay in proper diagnosis, the risk of complications due to time and progression of the disease, as well as procedures that some may have undergone. The incorrect extragonadal GCT diagnosis implies not treating the primary testicle, which may present partial regression, and, thus, in not responding to the systemic treatment and being maintained in a safe haven by the haemato-testicular barrier, it may become one of the most important factors determining recurrence and prognosis.

In our review of the literature, we found no conclusive publications on survival, the persistence of the disease or recurrence when compared to burned out GCT versus Gonadal and/or extragonadal GCT. In our case, the reported patients began a long-term follow-up protocol in order to carry out collaborative projects with other institutions in an attempt to answer the questions raised.

Conclusions

Throughout time, the evidence regarding the ‘phenomenon’ of testicular tumour regression has been described in various publications, which has allowed for its current definition as an entity with its own diagnostic criteria.

Etiopathogenesis is still not well defined, nor if the tumoural regression tumour itself has some value in the prognosis. What is well defined is the indication for treatment in accordance with GCT protocols.

‘Burned out’ GCTs are classified as metastatic or non-metastatic with complete or partial regression. The most frequent ones were metastatic with complete regression and the most common histological type was seminoma.

In all tumours with GCT clinical and/or histology, the primary testicular tumour should be ruled out before classifying it as an extragonadal GCT.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

The main idea and literature review were by JCA and MAA; the collection of data was done by FMA, BAL and JLD. Manuscript revision and approval of the final copy was done by all.

Acknowledgments

We thank the pathology laboratory staff: Medical Technologist Cinthya Ortiz and Biological Cytologist Oriana Vasquez.

References

- 1.Everson T, Cole W. Spontaneous regression of cancer. Ann Surg. 1956;144(3):366–380. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195609000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salman T. Spontaneous tumor regression. J Oncol Sci. 2016;2(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzer B, Ulbright T. Spontaneous regression of testicular germ cell tumors: an analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(7):858–865. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209831.24230.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulbright T, Amin M, Balzer B, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. 4th. Lyon: IARC; 2016. Tumours of the testis and Paratesticular tissue; pp. 185–258. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt M, Javadpour N. Germ-cell tumors in patients with apparently normal test. Cancer. 1981;47(7):1911–1915. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7<1911::aid-cncr2820470732>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comiter C, Renshaw A, Benson C, et al. Burned out primary testicular cancer: sonographic and pathological characteristics. J Urol. 1996;156:85–88. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholz M, Zehender M, Thalmann M, et al. Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor: evidence of origin in the testis. Ann of Oncol. 2002;13:121–124. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Extramiana J, De La Rosa F, Madero S, et al. “Burned-out” testicular tumor. Actas Urol Esp. 1986;10(5):289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trias I, Algaba F, Hocsman H. "Intratubular germ cell tumor: relation with "burned out" tumor and testicular germinal neoplasia. Eur Urol. 1991;19(1):81–84. doi: 10.1159/000473586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Deshmukh N, Gourevitch D, Taniere P, Wallace M, Cullen M. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a rare extragonadal presentation of seminoma of testis. Int J Urol. 2007;14:261–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulier B, Lefebvre Y, de Visscher L, et al. Metastases of clinically occult testicular seminoma mimicking primary. JBR–BTR. 2008;91:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesa H, Rawal A, Rezcallah A, et al. “Burned out” testicular seminoma presenting as a primary gastric malignancy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:74–77. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musser J, Przybycin C, Russo P. Regression of metastatic seminoma in a patient referred for carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrera J, Baztarrica G, España S, et al. Extragonadal germ-cell tumours with testicular “burned out” phenomenon. Rev Arg deUrol. 2011;76(1):22–27. phenomenon. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kar H, Kamer E, Ekinci N, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding as initial presentation of burned-out testicular tumor. UHOD. 2011;4(21):245–248. doi: 10.4999/uhod.09113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez R, Montoto P, Iglesias E, et al. Tumor de células germinales extragonadal con fenómeno “burned-out” simulando tumor retroperitoneal de estirpe neurogénico. Arch Esp Urol. 2012;65(10):900–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albany C, Einhorn L. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: clinical presentation and management. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:261–265. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835f085d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onishi K, Tomioka A, Maruyama Y, et al. Burned-out testicular tumor diagnosed triggered by paraneoplastic neurological syndrome: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2014;60(12):651–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George S, Al-Taleb A, Hussein S. Retrogressed (burned-out) testicular germ cell tumor disguising as duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Oncology Gastroenterology and Hepatology Reports. 2015;4(2):114–115. doi: 10.4103/2348-3113.152335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makino T, Konaka H, Namiki M. Clinical features and treatment outcomes in patients with extragonadal germ cell tumors: a single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishikawa H, Kawada N, Taniguchi A, et al. Paraneoplastic neurological syndrome due to burned-out testicular tumor showing hot cross-bun sign. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133:398–402. doi: 10.1111/ane.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juul M, Rasmussen E. A burned-out seminoma lymph node metastasis to the neck of a patient treated for colon cancer. Ugeskr Laeger. 2017;179(20):2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishisho T, Sakaki M, Miyagi R, et al. Burned-out seminoma revealed by solitary rib bone metastasis. Skeletal Radiol. 2017;46(10):1415–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2701-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freifeld Y, Kapur P, Chitkara R, et al. Metastatic “Burned Out” Seminoma Causing Neurological Paraneoplastic Syndrome—Not Quite “Burned Out”. Front Neurol. 2018;9(20) doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brimo F, Srigley J, Ryan C. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th. Chicago: Springer; 2017. Testis; pp. 727–735. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabre E, Jira H, Izard V, et al. Burned-out primary testicular cancer. BJU Int. 2004;94(1):74–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta N, MacFie T, MacDonald T, et al. Cancer immunoediting and spontaneous tumor regression. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosillo C, Scagnoli S, Pomati G, et al. Burned-Out Testicular Cancer: Really a Different History? Case Rep Oncol. 2017;10:846–850. doi: 10.1159/000480493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prym P. Spontanheilung eines bösartigen, wahrscheinlich chorionephiteliomatösen gewächses im hoden. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1927;265:239–258. doi: 10.1007/BF01894164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rather L, Gardiner W, Frerichs J. Regression and maturation of primary testicular tumors with progressive growth of metastases. Stanford Med Bull. 1954;12(1):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slater G, Schultz H, Kreutzmann W. Occult testicular tumor. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;157(11):911–912. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02950280035010e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azzopardi J, Mostofi F, Theiss E. Lesion of testis observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. Am J Pathol. 1961;38:207–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azzopardi J, Hoffbrand A. Retrogression in testicular seminoma with viable metastases. J Clin Path. 1965;18:135–141. doi: 10.1136/jcp.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veraguth P, Maillard G, MacGee W. Retroperitoneal seminomas without evidence of primary growth. Oncology. 1970;24:194–209. doi: 10.1159/000224520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson A, Calvert D, Codling B. The shrinking semonima. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:187. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naseem S, Azzopardi A, Shrotri N, et al. The shrinking seminoma – fact or fiction? Urol Int. 2000;65:208–210. doi: 10.1159/000064878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinagare A, Jagannathan J, Ramaiya N, et al. Adult extragonadal germ cell tumors. Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(4):274–280. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angulo J, González J, Rodríguez N, et al. Clinicopathological study of regressed testicular tumors (Apparent Extragonadal Germ Cell Neoplasms) J Urol. 2009;182:2303–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissen L, Brasseur P, Sukkarieh F. Spontaneous regression of testicular tumor. JBR-BTR. 2003;86(6):319–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontos S, Doumanis G, Karagianni M, et al. Burned-out testicular tumor with retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3(8705) doi: 10.4076/1752-1947-3-8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahoo P, Mandal P, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Burned Out Seminomatous Testicular Tumor with Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Metastasis: A Case Report. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4(4):390–392. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miacola C, Colamonico O, Bettocchi C, et al. Burned-out in a mixed germ cell tumor of the testis: The problem of pT0. Case report. Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia. 2014;86(4):389–390. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2014.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ichiyanagi O, Nagaoka A, Izumi T, et al. Suspicion of primary testicular germ cell tumor regressed completely before metastasis. Int Canc Conf J. 2013;3(2):87–90. doi: 10.1007/s13691-013-0121-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leleu O, Vaylet F, Debove P, et al. Pulmonary metastasis secundary to Burned-Out testicular tumor. Respiration. 2000;67:590. doi: 10.1159/000029579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Geraghty J, et al. Retroperitoneal seminoma with ‘burned out’ phenomenon in the testis. Int J Urol. 2005;12:115–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curigliano G, Magni E, Renne G, et al. “Burned out” phenomenon of the testis in retroperitoneal seminoma. Acta Oncologica. 2006;45:335–336. doi: 10.1080/02841860500401175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ha H, Jung S, Park S, et al. Retroperitoneal seminoma with the ‘Burned out’ phenomenon in the testis. Korean J Urol. 2009;50:516–519. doi: 10.4111/kju.2009.50.5.516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yucel M, Kabay S, Saracoglu U, et al. Burned-out testis tumour that metastasized to retroperitoneal lymph nodes: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3(7266) doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yucel M, Saracoglu U, Yalcinkaya S, et al. Burned-out testicular seminoma that metastasized to the prostate. Cent European J Urol. 2009;62(3):195–197. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2009.03.art15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orlich C, Jiménez E. Tumor testicular quemado. Regresión espontánea de un seminoma testicular (reporte de un Caso) Revista médica de Costa Rica y Centroamerica. 2010;LXVII(595):445–447. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaytán-Escobar E, Muñoz-Islas E, Colorado-García A, et al. Tumor testicular quemadocon metástasis pulmonares y retroperitoneales; informe de un caso. Rev Mex Urol. 2010;70(5):301–304. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaber S. Retroperitoneal mass and burned out testicular tumor. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21(3):542–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel M, Patel B. Sonographic and Magnetic Resonance imaging appearance of a burned-out testicular germ cell neoplasm. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:143–146. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung H, Woon M, Lo F. Burned-out testes seminoma without distant metastasis. Clinical Practice. 2014;3(1):4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Budak S, Celik O, Turk H, et al. Extragonadal germ cell tumor with the “burned out” phenomenon presented a multiple retroperitoneal masses: a case report. Asian J Androl. 2015;17:163–164. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.137481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasquez L, Frattini G, Fernández M. Burned out testis tumor, revision of their characteristics and presentation of three new cases. Rev Arg Urol. 2008;73(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balalaa N, Selman M, Hassen W. Burned-Out testicular tumor: A case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4:12–15. doi: 10.1159/000324041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gurioli A, Oderda M, Vigna D, et al. Two cases of retroperitoneal metastasis from a completely regressed burned-out testicular cancer. Urologia. 2013;80(1):74–79. doi: 10.5301/RU.2013.10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tasu J, Faye N, Eschwegw P, et al. Imaging of burned-out testis tumor: five new cases and review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22(5):515–521. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peroux E, Thome A, Geffroy Y, et al. Burned-out tumour; Retroperitoneal metastases; Ultrasound. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93:796–798. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El Sanharawi I, Correas J, Glas L, et al. Non-palpable incidentally found testicular tumors: Differentiation between benign, malignant, and burned-out tumors using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(11):2071–2082. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen B, Roarke M, Yang M. Intestinal metastases as an unusual presentation of a burned-out testicular seminoma: PET/CT imaging. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen. 2015;34(4):266–267. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCarthy W, Cox B, Laucirica R, et al. Fine Needle Aspiration Diagnosis of a Metastatic Mixed Germ Cell Tumor from a “Burned Out” Testicular Primary with Florid Leydig Cell Hyperplasia. Ann Clin Cytol Pathol. 2015;1(3):1013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parada D, Peña K, Moreira O, et al. Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumor: primary versus metastases? Arch Esp Urol. 2007;60(6):713–719. doi: 10.4321/S0004-06142007000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakazaki H, Tokuyasu H, Takemoto Y, et al. Pulmonary metastatic choriocarcinoma from a burned-out testicular tumor. Intern Med. 2016;55:1481–1485. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.5679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.López J, Angulo J. Burned-out tumour of the testis presenting as Retroperitoneal choriocarcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 1994;26:549–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02767657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tejido A, Villacampa F, Martín M, et al. Tumor testicular fundido. Arch Esp Urol. 2000;53(6):447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castillo C, Krygier G, Carzoglio J, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding as the first manifestation of a burned-out tumour of the testis. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7(10):458–463. doi: 10.1007/BF02716597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mola M, Gonzalvo V, Torregrosa M, et al. Tumor testicular bilateral “quemado” (“burn out”) Actas Urol Esp. 2005;29(3):318–321. doi: 10.1016/S0210-4806(05)73247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Preda O, Nicolae A, Loghin A, et al. Retroperitoneal seminoma as a first manifestation of a partially regressed (burnt-out) testicular germ cell tumor. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(1):193–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qureshi J, Feldman M, Wood H. Metastatic “Burned-Out” germ cell tumor of the testis. J Urology. 2014;192:936–937. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kebapci M, Can C, Isiksoy S, et al. Burned-out tumor of the testis presenting as supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:371–373. doi: 10.1007/s003300101038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Womeldorph C, Zalupski M, Knoepp S, et al. Retroperitoneal germ cell tumor diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2(12):443–445. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i12.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gomis C, Alcoba M, González R, et al. Tumor testicular quemado o burn-out tumor. 2015. XXX Reunión Nacional del Grupo de Urología Oncológica, España. En: [ www.aeu.es/aeu_webs/reuniones/oncologia2015/resumenGR.aspx?Sesion=4&Numero=P-23]

- 75.Hu B, Shah S, Shojaei S, et al. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection as first-line treatment of node-positive seminoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(4):e265–e269. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iwatsuki S, Naiki T, Kawai N, et al. Nonpalpable testicular pure seminoma with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein presenting with retroperitoneal metastasis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10(114) doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-0906-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ulloa–Ortiz O, Garza-Garza R, Hernán G, et al. Tumor extragonadal de células germinales con fenómeno de burned-out testicular. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología. 2017;16(5):307–310. [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Sharkawy M, Al-Jibali A. Burned-out metastatic testicular tumor: choriocarcinoma. Int J Health Sci. 2017;11(2):81–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]