The inferior olive is postulated to play a critical role in the generation of essential tremor (ET) and palatal tremor.1 The olivary hypothesis of ET stems mainly from the harmaline animal model, in which action tremor resembling ET is caused by harmaline‐induced olivary oscillation. However, human postmortem and neuroimaging studies have produced little support for the olivary hypothesis of ET.2 By contrast, there is considerable support for the olivary hypothesis of symptomatic palatal tremor, which occurs in the context of hypertrophic olivary degeneration.3 Lesions in the corticobulbocerebellothalamocortical loop reduce ET,4 but the effect of olivary lesions has not been reported on. Olivary hypertrophy is associated with progressive and profound loss of olivary neurons.5 We describe a patient with long‐standing ET that was not altered by bilateral olivary hypertrophy with palatal tremor.

This 77‐year‐old right‐handed man has more than a 30‐year history of hand tremor, which impairs his handwriting and fine motor control. His tremor has always affected his left hand more than the right, and it has gradually increased bilaterally over the past three decades. He is a retired electrician and was beginning to use both hands to perform some occupational tasks before his retirement at age 67. He has taken no medications for tremor and has not seen a physician for tremor. His mother had hand tremor in the latter half of her life, but his father did not. Both died of dementia at age 93. His two brothers (ages 65 and 75), two sons (ages 36 and 39), and daughter (age 38) do not have tremor.

In August 2014, he presented with a 2‐ to 3‐year history of progressive loss of balance and falls occurring an average of once per week. His gait imbalance began insidiously, and he was unsure of the time of onset. An MRI of the brain in July 2012 revealed bilateral olivary hypertrophy, and palatal tremor was observed by his referring physician in November 2013. He denied recent change in his tremor.

Neurological examination in August 2014 revealed a 2‐Hz palatal tremor, a wide‐based unsteady gait, and no extremity ataxia (see Video 1). The remainder of his neurological examination was unremarkable except for mild postural and kinetic tremor in his upper limbs, left greater than right. A follow‐up MRI in December 2013 was unchanged from July 2012. There was no abnormal T2 signal or atrophy elsewhere in the brainstem or cerebellum. Genetic testing was not done. A follow‐up neurological examination in May 2015 revealed no appreciable changes, but his balance was subjectively worse.

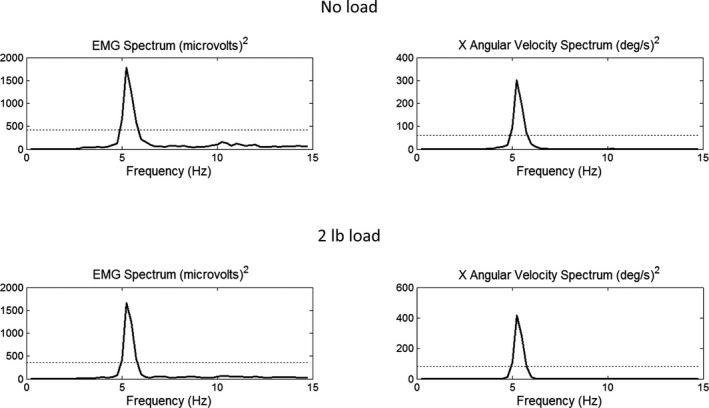

His tremor was assessed electrophysiologically in August 2014 and in May 2015, using a triaxial gyroscopic transducer mounted on the back of his right hand and surface electromyography (EMG) of the right extensor digitorum communis and extensor carpi radialis brevis. Postural tremor was recorded with the hand extended horizontally, palm down, and the forearm supported to the wrist. Spectral analysis revealed a 5.3‐Hz tremor that did not change when a 2‐pound (lb) load was attached to the hand (Fig. 1). Tremor frequency was the same in August 2014 and May 2015, and there was no change in amplitude.

Figure 1.

Spectral analysis of rectified low‐pass filtered EMG recorded from the right extensor carpi radialis brevis and angular velocity of the right hand, recorded with a gyroscopic transducer. Tremor frequency is 5.3 Hz with and without a 2‐lb load. The horizontal broken lines are the 95% confidence limits for a statistically significant spectral peak.

This patient developed the syndrome of progressive ataxia with palatal tremor at least 30 years after the onset of his ET. His ET has not changed despite 3 years of progressive ataxia, bilateral olivary hypertrophy, and persistent palatal tremor. Adult‐onset progressive ataxia with palatal tremor is a clinical syndrome with multiple etiologies.6 A recent postmortem study revealed a 4R tauopathy.7 More autopsy studies are needed.

Symptomatic palatal tremor is believed to emerge from abnormal 2‐Hz rhythmicity and synchrony in the hypertrophic olive, although this is still debated.3 Based on the harmaline tremor model in laboratory animals, the inferior olive is hypothesized to be the source of abnormal oscillation in ET. Our patient's 5.3‐Hz ET persists despite the presence of hypertrophic olivary degeneration and palatal tremor. Even if the inferior olives are not the source of 2‐Hz palatal tremor, they are undergoing a progressive hypertrophic degeneration with severe neuronal loss, which has not affected our patient's hand tremor. Interestingly, a more advanced patient with progressive ataxia and palatal tremor was previously studied electrophysiologically in our lab and was found to exhibit enhanced mechanical‐reflex tremor resulting from periodic inhibition of forearm EMG at 1.9 Hz, synchronous with the 1.9‐Hz palatal tremor.8 By contrast, the present patient exhibited a central neurogenic tremor at 5.3 Hz, typical of ET.

We conclude that the inferior olives are not the source of ET in our patient. Our patient has classic or definite ET according to the consensus criteria of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society and the criteria of the Tremor Investigation Group.9 However, ET is a syndrome, not a specific disease,10 and our conclusions may not apply to all patients with ET.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

A.E.: 1B, 1C, 2B, 2C, 3A

J.K.: 1C, 2C, 3B

R.E.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: This work was supported by a grant from the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of Kiwanis International, Illinois‐Eastern Iowa District. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 years: R.E. received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Spastic Paralysis Research Foundation of Kiwanis International, Illinois‐Eastern Iowa District.

Supporting information

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The patient's palatal tremor, upper‐limb tremor, and gait are shown, followed by proton density and T2 axial images of his olivary hypertrophy, obtained in December 2013. He had difficulty achieving a “wing‐beating” posture because of an arthritic left shoulder with rotator cuff failure.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Park YG, Park HY, Lee CJ, et al. Ca(V)3.1 is a tremor rhythm pacemaker in the inferior olive. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:10731–10736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Louis ED. From neurons to neuron neighborhoods: the rewiring of the cerebellar cortex in essential tremor. Cerebellum 2014;13:501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shaikh AG, Hong S, Liao K, et al. Oculopalatal tremor explained by a model of inferior olivary hypertrophy and cerebellar plasticity. Brain 2010;133(Pt 3):923–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dupuis MJ, Evrard FL, Jacquerye PG, Picard GR, Lermen OG. Disappearance of essential tremor after stroke. Mov Disord 2010;25:2884–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishie M, Yoshida Y, Hirata Y, Matsunaga M. Generation of symptomatic palatal tremor is not correlated with inferior olivary hypertrophy. Brain 2002;125(Pt 6):1348–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Samuel M, Torun N, Tuite PJ, Sharpe JA, Lang AE. Progressive ataxia and palatal tremor (PAPT): clinical and MRI assessment with review of palatal tremors. Brain 2004;127(Pt 6):1252–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mari Z, Halls AJM, Vortmeyer A, Zhukareva V, Uryu K, Lee VM‐Y, Hallett M. Clinico‐pathological correlation in progressive ataxia and palatal tremor: a novel tauopathy. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2014;1:50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elble RJ. Inhibition of forearm EMG by palatal myoclonus. Mov Disord 1991;6:324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Mov Disord 1998;13(Suppl 3):2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elble RJ. What is essential tremor? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013;13:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. The patient's palatal tremor, upper‐limb tremor, and gait are shown, followed by proton density and T2 axial images of his olivary hypertrophy, obtained in December 2013. He had difficulty achieving a “wing‐beating” posture because of an arthritic left shoulder with rotator cuff failure.