Abstract

The goal of the present study was to describe a case of perilymphatic fistula (PLF) of the round window (RW) that occurred after sneezing, along with a review of the literature. We report a case of PLF of RW, which was provoked by sneezing, and its consequent medical and surgical treatments. With respect to the review of the literature, articles were initially selected based on their titles or abstracts, followed by methodological evaluation. The patient underwent an explorative tympanotomy (ET) with packaging of RW with the pericondrium, following which the patient’s complaints regarding vertigo and imbalance disappeared, but the severe sensorineural hearing loss persisted. For the literature review, five references were selected. These studies showed a great variety in the clinical presentation and healing of symptoms. Sneezing represents a rare but well-recognized cause of PLF, as reported in our case. The correct selection of patients who should undergo ET and an early surgical repair of PLF are mandatory for better outcomes, especially in case of hearing.

Keywords: Fistula, perilymphatic, round, sneezing, window

INTRODUCTION

The term perilymphatic fistula (PLF) refers to an abnormal communication between the middle ear and perilymphatic space through the oval window (OW) and round window (RW). It can be due to a congenital otologic disorder, such as malformations or syndromic diseases, or can be an acquired condition that is provoked by factors, such as iatrogenic or physical injuries [1].

The first report of a nonsurgical PLF was presented by Fee [2], followed by Stroud and Calcaterra in 1970 [3]. Goodhill [4] proposed an etiological theory on the basis of idiopathic rupture of OW and/or RM membranes: implosive (as during Valsalva’s maneuver) or explosive (as for increased intracranial pressures) force can cause membranous lacerations with consequent formation of fistulas.

In case of rupture of RW, patients complain about hearing loss of different grades (even profound deafness), tinnitus, and vertigo with various intensities, alone or in combination. The variety of manifestations and controversial diagnostic tests lead to a difficult classification of this pathological entity.

The aim of our study was to analyze the clinical characteristics, management, therapeutic options, and consequent results of PLF using a case of RW membrane rupture that occurred after sneezing and systematically reviewing the literature pertaining to this topic.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old woman consulted the ear-nose-throat emergency unit for sudden left hearing loss and instability following a sneeze. An otoscopic examination was unremarkable. Pure tone audiometry demonstrated a profound (>90 db) flat sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL) of the left ear; tympanogram was type A bilaterally, whereas left cochlear stapedial reflex was absent on ipsilateral and controlateral stimulation of the right ear. No spontaneous or positional nystagmus was described on bedside examination with Frenzel glasses. After a week of oral corticosteroid (CS) therapy, SSHL persisted; hence, the patient came to our hospital. Pure tone audiometry conducted at our unit showed a severe flat SSHL of the left ear. On infrared videonistagmoscopy (ICS Chartr 200; Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark), a low-amplitude horizontal, left-beating spontaneous nystagmus was noted with positional geotropic increase. The nystagmus was inhibited by fixation. A fistula test with pressure on the left ear canal increased the intensity of the nystagmus, so an explorative tympanotomy (ET) was performed a day later under general anesthesia due to a suspected PLF. A transcanal approach with tympanomeatal flap elevation enabled the observation of a perilympathic leakage from RW (Figure 1a and b), which was packed with pericondrium reinforced by fibrin glue (Tissucol; Baxter AG, Wien, Austria). Dizziness and instability immediately disappeared with spontaneous nystagmus; however, unfortunately, the hearing loss persisted 1 month after the surgery.

Figure 1. a, b.

Round window (a) and round window with evidence of perilymphatic leakage (b).

Search strategy for the review of the literature

The search strategy was designed to include articles based on their topic.

The inclusion criteria were based on the type of the study: articles on clinical manifestations, diagnostic tools, possible therapies, and pitfalls of PLF of RW caused due to sneezing.

To identify relevant studies, as the first step, a search was conducted on Google and MEDLINE databases using a combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to PLF of RW (e.g., spontaneous or idiopathic PLF, barotraumas and PLF, rupture of round window, sternutatory event, sneezing, sudden sensorineural hearing loss).

This first step enabled the identification of a list of potential citations for inclusion in this review. Titles and abstracts of these articles were then screened.

The data regarding the demographic features of the sample population, symptoms, diagnostic tools, medical versus surgical therapy, and results were arranged in descriptive tables.

Literature search

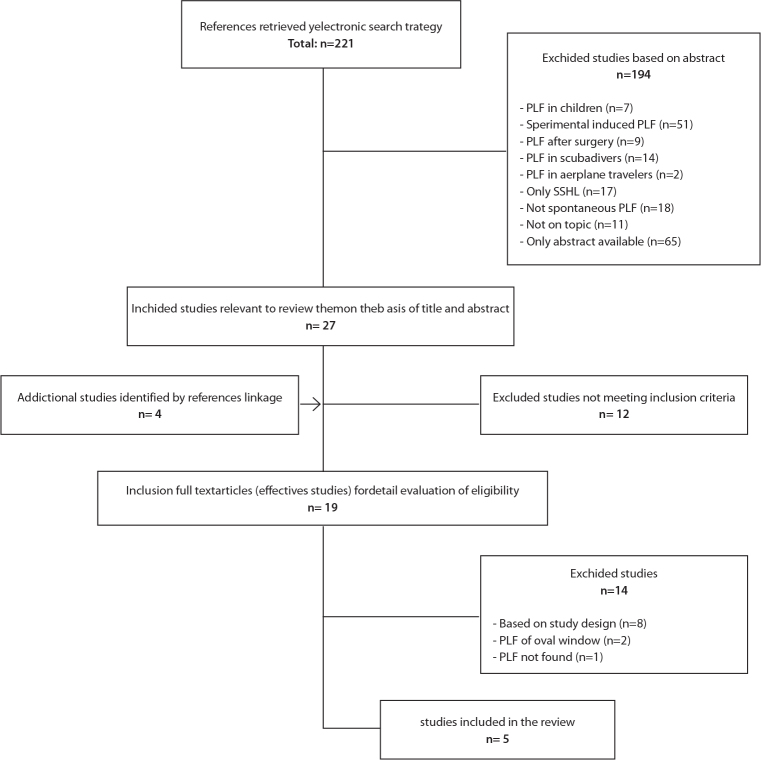

A total of 221 citations were retrieved from the first phase of the search, of which 194 were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts. Full texts of the remaining 27 articles were retrieved, along with four additional full-text articles that were identified as potentially relevant by the second-step search expansion. Based on the inclusion criteria, five articles were selected for inclusion in this review (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram

Overview of analyzed studies

Of the five studies included in the review, only one [5] was a case report of two patients.

The demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed studies

| Auth. | n. pat. | Sex | Mean age (y) | PLF of OW | PLF of RW | Vertigo | SHL | Tinn. | Side + audiom. exam | Other | Fistula test | Imaging | VNG | Reconst. material | Results: vertigo | Results: SHL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Althaus 1977 [6] | 6 | 4 M (66%) 2 F (33%) | 44.33 (29–55) | 5 (83%) | 1 (16%) | 100% | 100% | 50% | 100% left SHL; different grades | 1 otitic meningitis (16%) | 1 pos. (16%) | 100 % RX neg. | 66% left-beating positional Ny | 100% fat | 83% improved | 50% improved |

| Al Felasi et al. 2011 [5] | 2 | M | 1) 43 2) 45 |

- | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1) Right mixed HL, then SHL 2) Left SHL |

/ | Neg. | 1) CT: dislocated stapes | 1) no Ny 2) left vestib. deficit |

Temp. fascia | 1) improved 2) not improved |

1) improved 2) not improved |

| Haubner et al. 2012 [8] | 69 | 39 M (56%) 30 F (43%) | 56.9 (17–92) | - | 100% | 44.9% | 100% | 50.7% | 56.3% left SHL; 43.5% right HL | Expl.tymp: 59.4% no PLF 18.8% Rw PLF 21.7 doubt |

- | - | - | 81.2% fat 11.5% temp. fascia 7% both |

- | 53% improved |

| Nagai and Nagai 2012 [9] | 34 (35 ears) | 19 M (56%) 15 F (44%) | median 47.4 | 9 (26%) | 3 (8%) | 18 (53%) | 100% | - | 100% SHL 45.7% severe* 42.8% profound* Rw PLF 11.4% total* |

23 (66%) both Ow and | - | CT neg. | - | 100% temp. fascia | - | Improved SHL 53% severe* 73% profound* 25% total* |

| Park et al. 2012 [7] | 9 (10 ears) | 4 M (44%) 5 F (55%) | 32 (12–62) | 2 (20%) | 6 (60%) | 100% | 100% | - | 100% SHL different grades (10% bilateral) | 10% no PLF 100% improved 10% both Ow and Rw PLF |

- | - | 10% spontaneous horizontal Ny | Soft tissue | 100% resolved | Not improved |

| Our | 1 | F | 52 | -- | Yes | -- | Yes | - | Left SHL | - | - | - | - | Pericondr. | - |

Auth = authors; n = number; pat = patients; y = years; OW = oval window; PLF = perilymphatic fistula; RW = round window; SHL = sensorineural hearing loss; tinn = tinnitus; audiom = audiometric; VNG = videonystagmography; reconst= reconstruction; M = male; F = female; pos = positive; RX = radiography; neg = negative; Ny = nystgamus; CT = computed tomography; vestib = vestibular; temp = temporalis; expl tymp = exploratory tympanotomy; doubt = doubtful; pericondr = pericondrium

severe = <60–89 dB; profound = <90–110 dB; total = <111 dB

All the patients (100%) complained of SSHL (left side was the most affected), whereas vertigo and tinnitus were present in variable percentages.

Vestibular testing revealed a positional nystagmus in 66% of patients included in the study conducted by Althaus [6]; vestibular deficit was described in one patient [5] and spontaneous horizontal nystagmus in one [7].

Fistula test showed positive results in one patient [6] and negative in another [5]. Only Al Felasi et al. [5] demonstrated a dislocation of the stapes on computed tomography (CT).

ET was performed in all the reports. Haubner et al. [8] and Park et al. [7] described that 59.4% and 10% of patients did not show PLF during ET, respectively, despite the symptoms. On the other hand, two studies [7, 9] reported PLFs of both the membranous windows.

Reconstruction material included temporalis fascia in most surgeries. The outcomes related to vertigo and resolution of the hearing loss were not homogeneous (Table 2). Not all the patients underwent CS therapy before surgical intervention, and ET was conducted after a maximum of 47 days from the day of symptom onset [7] (Table 2). In all the cases of delayed ET, PLF was found, and no patient showed spontaneous healing.

Table 2.

Causes and therapeutic choices of reviewed studies on PLF of the RW

| Authors | Causes of PLF of the RW | CS therapy | Exploratory tympanotomy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Althaus 1977 [6] | Heavy lifting | No | First therapeutic choice |

| Al Felasi et al. 2011 [5] | 1) Slap 2) Nose blowing |

1) No 2) Yes (1 week) |

1) First therapeutic choice 2) After 2 weeks* |

| Haubner et al. 2012 [8] | 89.8% ? 10.2% physical exercise, diving, head trauma, noise exposure |

Yes | After 48 h* |

| Nagai and Nagai 2012 [9] | 26.4% head trauma 20.5% heavy lifting 11.7% nose blowing 0.6% noise exposure |

Yes | After 8.5 days (median)* |

| Park et al. 2012 [7] | 20% slap 20% head trauma 10% heavy lifting 30% nose blowing 20% intense Valsalva maneuver |

66% yes | From 2 days to 47 days* |

| Our | Sneeze | Yes (1 week) | After 8 days* |

CS: corticosteroid

from symptoms’onset

DISCUSSION

The diagnostic criteria for PLF are not well-established. The criteria suggested by the Japanese Intractable Hearing Loss Research Committee of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Japan revised in 2016) are based on the following points:

Symptoms (hearing impairment, tinnitus, aural fullness, and vestibular symptoms associated with barotraumas and/or co- or pre-existing middle and/or inner ear disease/surgery)

Laboratory findings (microscopic/endoscopic inspection, and/or biochemical tests)

References (β2 transferrin, Cochlin-tomoprotein detection test, idiopathic cases)

Differential diagnosis (inner ear diseases with known causes)

Definite diagnosis (ET, detection of perilymph-specific protein) [10]

The main challenge in the diagnosis of PLF is the similarity of symptoms with those of Ménière syndrome [11] and mostly variable clinical history. While there is a general consensus about the traumatic origin of PLF, the existence of idiopathic or spontaneous PLF remains debatable. Therefore, Shea [12] stressed that this “mythological” pathological entity was due to a traumatic event forgotten by the patients who often do not pay attention to irrelevant events, such as heavy lifting, laughing, singing, or sneezing. It is possible that when a patient performs a Valsalva maneuver to improve auricular fullness, spontaneous healing of PLF becomes more difficult, and the correct diagnosis may be delayed.

With regards to spontaneous labyrinthine fistulas, Collinson and Pons [1] presented a case report of PLF of OW and highlighted the presence of otoacustic emissions due to distortion, demonstrating the intact outer hair cell function. Another example of PLF of OW was proposed by Pyykkö et al. [13], who reported a set of subjects with different inner ear pathologies that were clinically compatible with PLF: only one patient showed OW membrane laceration, whereas others were affected by Ménière syndrome, various vestibulopathies, or cochleopathies (16 cases due to previous stapes surgery). Moreover, the study of Hoch et al. [14] found no PLF on ET despite symptoms suggestive for labyrinthine fistula.

Sneezing, in particular, represents a defensive mechanism which allows to expel irritating particles from the nasal cavity. It provokes the lowering of the soft palate and palatine uvula, with elevation of the tongue, thereby permitting an explosive expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth with varying force, entity, and extent [15].

In case of sneezing, as in our report, the mechanism underlying the rupture of RW membrane may involve an increase in the cerebrospinal fluid pressure which is diffused to the labyrinth through the cochlear aqueduct or internal auditory canal [7].

In the literature, other reports of sudden hearing loss following a sneeze were present, but none reported an RW fistula. These articles were presented by Azem and Caldarelli [16], Whitehead [17], and Bonfils et al. [18]. Azem and Caldarelli [16] described a conductive hearing loss due to stapedial fracture provoked by a sneeze and did not mention any PLF. Whitehead [17] presented three patients with SSHL: one following parturition and two following sneezing; in one case, PLF of OW was described, whereas in the last one, there was no evidence of perilymphatic leakage. Bonfils et al. [18] did not perform ET, so PLF was not described.

Regarding audiometric findings of PLF, Park et al. [7] noted a descending configuration in most cases, indicating that the basal cochlear turn was more prone to damage because of its closeness to OW and RW. There is an experimental demonstration of alteration in the vibratory function of the cells in the organ of Corti due to an abrupt pressure imbalance provoked by the presence of PLF of RW; the consequent change in the summating potential may be an etiological factor for SSHL in case of PLF [19].

The predilection for the left side noted in the literature may be related to larger left cochlear aqueducts found in most human skulls, but this still remains a conjecture [6].

Kohut et al. [11] recognized some objective diagnostic criteria for PLF: presence of sudden or fluctuating hearing loss (unresponsive to CS therapy), vestibular symptoms mimicking a positional vertigo, and constant disequilibrium. These represent very unspecific findings; furthermore, fistula test is a very specific but poorly sensitive diagnostic tool. Positive test results strongly suggest the presence of PLF, but negative results cannot rule out the presence of such a lesion [6]. However, our case underlined the importance of evaluating patients using videonystagmoscopy because the nystagmus may be of very low amplitude.

Based on the above discussion, it is mandatory to identify and select candidates for surgical exploration, considering the possibility of using less invasive diagnostic tools, such as the detection of perilymph-specific protein [20–22], neurophysiological tests (electrocochleography), multifrequency tympanometry [23], instrumental examination (vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials) [24], and low-frequency sound stimulation during posturography [25].

According to Nagai et al. [9], the indication for ET in case of SHL is progressive hearing loss, acute hearing loss with vertigo, acute hearing loss with the presence of positional nystagmus in a spinal position, or unresponsiveness to CS therapy. On the contrary, our report demonstrated that a prolonged CS therapy in patients with strongly suspected PLF and consequently delayed ET can lead to an irreversible hearing damage and failure of relief from vestibular symptoms. Furthermore, in our opinion, not all patients with SHL who have progressive hearing loss or are unresponsive to CS therapy are candidates for ET.

While performing surgical exploration, the criteria to confirm PLF of RW are as follows: actual observation of fluid leakage from RW, direct inspection of membrane rupture, and no simultaneous transmission of pressure from OW to RW [9]. Despite these clear definitions, assessment of PLF can remain doubtful in some circumstances [8], provoked, for instance, by scarred membranes or solid ridges in the proximity of the site of interest. The use of alternative methods, such as intratecal fluorescein, remains controversial [8].

Previous studies have underlined how vestibular outcomes are generally better than hearing outcomes after surgery [7, 26, 27], and our report confirmed this aspect.

In all the five studies analyzed in our review, there was no correlation between the material used for RW membrane reconstruction and possible healing.

The timing for ET and surgical outcomes were variable; however, the findings suggested that an early fistula repair can increase the chance of hearing recovery. In fact, persistent perilymphatic leakage can lead to an irreversible damage of the inner ear, as shown in our case report. Moreover, all other active therapeutic options, which are more or less invasive, including the use of autologous intratympanic blood patch, can be considered [28, 29].

CONCLUSION

The heterogeneity of clinical presentations, often combined with inaccurate history, makes the diagnosis of PLF challenging for ENT specialists. Among the causes of PLF, sneezing is a well-known entity, but our report represented a rare case. The cornerstone in PLF management remains the correct selection of patients for surgical exploration and early surgical repair of the membrane rupture for better hearing outcomes. In particular, when PLF is strongly suspected in case of history of trauma, followed by hearing loss associated with vestibular symptoms, especially disequilibrium rather than vertigo or dizziness, the use of ET is justified [30].

Footnotes

Informed Consent: Written inform consent was obtained from patients who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed

Author contributions: Concept - F.C.; Design - F.C., M.M.; Supervision - F.C.; Resource - F.C., M.M.; Materials - F.C., M.M.; Data Collection and/or Processing - F.C., M.M.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - F.C., M.M.; Literature Search - F.C., M.M.; Writing - F.C., M.M.; Critical Reviews - F.C.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collinson PJ, Pons KC. “Spontaneous” perilymph fistula: a case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:329–34. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fee GA. Traumatic perilymph fistulas. Arch Otolaryngol. 1968;88:477–80. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1968.00770010479005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stroud MH, Calcaterra TC. Spontaneous perilymph fistula. Laryngoscope. 1970;80:479–87. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodhill V. Sudden deafness and round window rupture. Laryngoscope. 1971;81:1462–74. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197109000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Felasi M, Pierre G, Mondain M, Uziel A, Venail F. Perilymphatic fistula of the round window. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:139–41. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althaus SR. Spontaneous and traumatic perilymph fistulas. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:364–71. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park GY, Byun H, Moon IJ, Hong SH, Cho YS, Chung WH. Effects of early surgical exploration in suspected barotrumatic perilymph fistulas. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;5:74–80. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2012.5.2.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haubner F, Rohrmeier C, Koch C, Vielsmeier V, Strutz J, Kleinjung T. Occurrence of round window membrane rupture in patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2012;12:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagai T, Nagai M. Labyrinthine window rupture as a cause of acute sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1584-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuda H, Sakamoto K, Matsumura T, Saito S, Shindo S, Fukushima K, et al. A nationwide multicenter study of the Cochlin tomo-protein detection test: clinical characteristics of perilymphatic fistula cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:S53–S59. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2017.1300940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohut RI, Hinojosa R, Thompson JN, Ryu JH. Idiopathic perilymphatic fistulas: a temporal bone histopathologic study with clinical, surgical, and histopathologic correlations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:412–20. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890120092023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea JJ. The myth of spontaneous perilymph fistula. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:613–6. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyykkö I, Selmani Z, Zou J. Low-frequency sound pressure and transtympanic endoscopy of the middle ear in assessment of “spontaneous” perilymphatic fistula. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:137623. doi: 10.5402/2012/137623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoch S, Vomhof T, Teymoortash A. Clinical evaluation of round window membrane sealing in the treatment of idiopathic sudden unilateral hearing loss. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;8:20–5. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2015.8.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yenigun A. Sudden post-traumatic sensorineural hearing loss reverted to normal by sneezing. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2014;2:2050313X14564774. doi: 10.1177/2050313X14564774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azem K, Caldarelli DD. Sudden conductive hearing loss following sneezing. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;97:413–4. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1973.00780010425015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehead E. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss with fracture of the stapes footplate following sneezing and parturition. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24:462–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonfils P, Laccourreye O, Durand FX, Malinvaud D, Bensimon JL. Sudden deafness following a sterutatory attack. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:103–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funai H, Hara M, Nomura Y. An electrophysiologic study of experimental perilymphatic fistula. Am J Otolaryngol. 1988;9:244–55. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(88)80034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bluestone CD. Implications of beta-2 transferrin assay as a marker for perilymphatic versus cerebrospinal fluid labyrinthine fistula. Am J Otol. 1999;20:701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikezono T, Shindo S, Sekiguchi S, Morizane T, Pawankar R, Watanabe A, et al. The performance of Cochlin-tomoprotein detection test in the diagnosis of perilymphatic fistula. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15:168–74. doi: 10.1159/000241097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kataoka Y, Ikezono T, Fukushima K, Yuen K, Maeda Y, Sugaya A, et al. Cochlin-tomoprotein (CTP) detection test identified perilymph leakage preoperatively in revision stapes surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40:422–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sass K, Densert B, Magnusson M. Transtympanic electrocochleography in the assessment of perilymphatic fistulas. Audiol Neurootol. 1997;2:391–402. doi: 10.1159/000259264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modugno GC, Magnani G, Brandolini C, Savastio G, Pirodda A. Could vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) also be useful in the diagnosis of perilymphatic fistula? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:552–5. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selmani Z, Ishizaki H, Pyykkö I. Can low frequency sound stimulation during posturography help diagnosing possible perilymphatic fistula in patients with sensorineural hearing loss and/or vertigo? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:129–32. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0614-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.House JW, Morris MS, Kramer SJ, Shasky GL, Coggan BB, Putter JS. Perilymphatic fistula: surgical experience in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:51–61. doi: 10.1177/019459989110500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black FO, Pesznecker S, Norton T, Fowler L, Lilly DJ, Shupert C, et al. Surgical management of perilymphatic fistula: a Portland experience. Am J Otol. 1992;13:254–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster PK. Autologous intratympanic blood patch for presumed perilymphatic fistulas. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:1158–61. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116009580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinohara T, Gyo K, Murakami S, Yanagihara N. Blood patch therapy of the perilymphatic fistulas--an experimental study. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho. 1996;99:1104–9. doi: 10.3950/jibiinkoka.99.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hornibrook J. Perilymph fistula: fifty years of controversy. ISRN Otolaryngology. 2012;2012:281248. doi: 10.5402/2012/281248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]