Abstract

Introduction

Senior trainees (residents) are poised to be unique effectors of clinical feedback. While several curricula are available to teach residents to give or elicit feedback, our curriculum is unique in that it teaches both the giving and elicitation of feedback and focuses on the longitudinal coaching relationship as opposed to onetime feedback interactions. This curriculum provides a framework, called clinical coaching, for streamlining and enhancing feedback interactions between senior and junior trainees.

Methods

This curriculum consists of: (1) a video module, (2) an interactive workshop, and (3) role-plays. Participants view the module, which simulates traditional feedback contrasted with the suggested approach. Next, an interactive workshop stimulates reflection on feedback, then defines and demonstrates clinical coaching. Finally, participants practice coaching with prewritten scenarios that illustrate critical steps in clinical coaching.

Results

This workshop was initially conducted in September 2014 with 50 participants. Thirty-nine house staff completed the postcurricular survey (13 had attended the workshop, 26 had not). Recognition of interns soliciting feedback one or more times per week was greater amongst workshop attendees (83% of residents, 78% of interns), as compared to nonattendees (53% of residents, 67% of interns). Preparation to give feedback differed amongst resident attendees versus nonattendees (0% vs. 19%, respectively, reported no preparation).

Discussion

These results highlight a need to increase awareness of and preparedness for the vital role that trainees can play in coaching. Training house staff in coaching has the potential to transform feedback for teachers and learners alike.

Keywords: Feedback, Residents as Teachers, Peer Assessment, Clinical Coaching

Educational Objectives

Upon completion of this curriculum, participants will be able to:

-

1.

Define key behaviors for both the coach (senior trainee) and the apprentice (junior trainee).

-

2.

Rate as important the active roles for both coach and apprentice.

-

3.

Develop a plan to increase the frequency and recognition of coaching interactions.

-

4.

Demonstrate the ability to incorporate key coaching behaviors into their coaching interactions.

Introduction

In medical education—both undergraduate and graduate—trainees learn to a large extent from one another.1 House staff spend as much as 20% of their clinical time in a teaching role, and medical students recognize house staff as their teachers for up to one-third of clinical knowledge.2 In one survey, interns ranked senior residents above both attending physicians and fellows in terms of importance to clinical education.3 In acknowledgment of the vital and increasing role of residents as teachers, regulatory bodies such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) require that residents receive formal instruction and evaluation in teaching skills.4,5 However, many trainees report feeling insufficiently prepared to teach. A 2001 study reported that only 50% of residency programs in the U.S. offered formal teaching skills curricula,6 and in a more recent study, only 7% of trainees reported feeling appropriately prepared to teach.7

Evaluation in the form of feedback is one vital component of clinical teaching.8 Often, feedback is given via the method of the feedback sandwich, a technique of delivering negative criticisms sandwiched between positive comments.9 This approach emphasizes single encounters and delivery of feedback, which is only an active process for the giver of feedback (and inactive for the recipient), and does not pay heed to relationships between individuals. This evaluative paradigm emphasizes the responsibility of the individual giving feedback, with little to no focus on the role of the receiver of feedback.10

The effectiveness of this method of evaluation is not well understood, and there is limited evidence regarding best practices for feedback in general.11 What is evident is that trainees report being dissatisfied with the frequency, content, and quality of feedback, and this dissatisfaction is common across specialties.12–15 Moreover, studies have consistently shown that while medical students and residents perceive they do not receive enough feedback, evaluating faculty report that they provide adequate feedback but that it is not adequately recognized by trainees.16,17

Residents are uniquely positioned to be effective givers of feedback and thereby address this gap in perspective between given and received feedback. Residents have substantial overlap with and opportunity to observe junior trainees, more so than attending physicians; residents observe junior trainees more frequently, in a variety of contexts, and often over a longer period of time. Residents report that attending physicians cannot provide effective feedback because of insufficient time spent working together; trainees are therefore more likely to seek peer feedback due to ongoing exposure and longitudinal relationships.10

We present an approach to ongoing assessment and feedback developed specifically for the resident. This dynamic, multistep process is best described as clinical coaching. We define clinical coaching as a longitudinal helping relationship between coach and apprentice that provides continuing feedback on and assistance with improving performance. Here, coach is defined as the more senior trainee (supervising resident), and apprentice is defined as the more junior trainee (intern or medical student).

Although several curricula are available on MedEdPORTAL to teach residents how to give feedback, the majority focus on the role of the giver of feedback.18–20 Two curricula emphasize the importance of learners eliciting feedback and teach these skills21,22; only one also teaches learners how to utilize feedback.23 The curriculum presented here is unique in that it simultaneously teaches both the giving and elicitation of feedback to a group of learners; we believe this to be important as residents and interns regularly are in a position to both give and receive feedback. Additionally, our curriculum emphasizes active participation via role-play, allowing learners to practice the sometimes uncomfortable feedback process. Furthermore, unlike curricula focused on onetime feedback interactions, our curriculum emphasizes the longitudinal aspect of coaching that we believe residents are uniquely positioned to accomplish.

This curriculum was developed as part of a larger graduate medical education teaching skills curriculum at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and was first piloted and studied within the internal medicine residency program. It is designed to be adapted for use with trainees from any discipline.

We have distilled the critical components of clinical coaching into the following mnemonic steps:

-

•

For the coach, COACH:

-

1.

C—create the coaching environment: The coach sets expectations for an ongoing relationship, identifies specific areas for coaching, and creates an environment that is helping, trusting, and safe.

-

2.

O—observe/prepare: The coach reflects on the apprentice's strengths/weaknesses, gathering specific examples. These should include consideration of the apprentice's current status, past performance, interval change, and future goals.

-

3.

A—assemble/meet: The coach decides on an appropriate setting, depending upon the sensitivity of the subject matter. The conversation is initiated with a provocative question, following the model of “Ask, share, then ask some more.” Here, the coach shares specific examples of behavior or skill, exploring reasons for deficits and strategies for improvement. Together, the coach and apprentice plan the next steps.

-

4.

CH—check/follow-up: Using the previously constructed learning plan, the coach checks on the apprentice's progress.

-

1.

-

•

For the apprentice, DIRECT:

-

1.

DI—decide/identify focus: Prior to interacting with the coach, the apprentice identifies specific needs for coaching.

-

2.

R—reflect: The apprentice reflects on his/her performance, including strengths/weaknesses, using specific examples.

-

3.

E—elicit: The apprentice actively approaches the coach to ask for assessment using the model of “Share, then ask,” wherein he/she uses self-observations as a stimulus to elicit recommendations from the coach.

-

4.

C—clarify: The apprentice asks clarifying questions where ambiguities exist.

-

5.

T—translate into action: Together, the coach and apprentice develop shared goals and set a specific plan for follow-up.

-

1.

In order to be effective in the climate of modern residency training, clinical coaching must respect the multiplicity of constraints on trainee time by being integrated into the daily workflow. Our curriculum, similarly, has been created to fit into the existing structure of a resident teaching conference or development retreat.

Methods

This curriculum consists of four components: (1) introduction, (2) video module, (3) interactive workshop, and (4) role-play scenarios. Each component is described below, contained in various Appendices, and referenced in the Interactive Workshop Run Sheet (Appendix C). The curriculum is designed to take place in a contained 60-minute in-person session, ideally at a prespecified resident conference time. A room where chairs/tables can be rearranged so participants are facing one another in order to facilitate discussion, is recommended, as is an AV system with internet access and projection capability. Appendix B contains a PowerPoint presentation that the facilitator can use to facilitate the workshop.

Introduction

Supplies needed for the introduction include two 3×5 notecards per participant. The facilitator opens the session with the objectives slide from the PowerPoint, then asks participants to reflect on their immediate responses to the words Feedback and Coaching. Participants write one-word responses on each side of one of the notecards handed to them when they entered.

As an optional activity, facilitators can create a word cloud with these responses, as a visual representation of participants' reactions to the two words. For example, we used the Wordle website to create the word cloud shown in Figure 1 for Feedback.

Figure 1. Word cloud for Feedback.

Video Module

The Clinical Coaching Module (Appendix A) is shown at the indicated point in the PowerPoint presentation, simulating a traditional feedback sandwich interaction and a clinical coaching interaction. The core concepts and key steps of clinical coaching are introduced in this video, including the COACH and DIRECT mnemonics.

Reflection

After watching the video module, participants take part in a reflection exercise consisting of small-group discussion, large-group sharing, and knowledge review. An easel or whiteboard is useful, but optional, for this reflection.

Reflection Time line

-

1.

Small-group discussion (self-reflection): 10 minutes. The facilitator divides the participants up into groups of five, separated by level of training (e.g., interns separate from residents). The following questions are shown to the large group on the PowerPoint slide (Appendix B) to prompt independent and group reflection. The facilitator asks for a volunteer or identifies a group leader to present the group's collective thoughts at the conclusion of the activity.

-

•

Prompt: Think about your last feedback interaction.

-

•Intern questions:

-

○Do you think that interaction was effective? If yes, why? If no, why?

-

○What is your role in obtaining feedback from your resident?

-

○

-

•Resident questions:

-

○Do you think this interaction was effective? If yes, why? If no, why?

-

○What do you feel is your role in helping medical students and interns to improve?

-

○

-

•

-

1.

Group leaders share reflections: 5 minutes. As an option, the facilitator can write notes on an easel or whiteboard as the reflections are shared.

-

2.

Knowledge review: 5 minutes. Using the group responses as a launching point, the facilitator distills these concepts into a brief review of key elements of the COACH and DIRECT paradigms (previously introduced in the video module and projected via PowerPoint). Time is allowed for comments from participants.

Role-Play Scenarios

Time line

-

1.

Role-play: 10 minutes. The participants break into pairs of two, one intern and one resident. Each participant is provided with a detailed written stem outlining a clinical scenario (provided in Appendix D). Participants receive stems specific to their role in the coaching interaction (i.e., resident as coach, intern as apprentice). They then proceed to engage in either a role-play or a discussion of a coaching interaction.

-

2.

Group reflection: 10 minutes. When the group reassembles, volunteers verbally reflect on their experience by referring to the COACH/DIRECT mnemonics, highlighting behaviors that felt natural and those that were more difficult. The facilitator should read the clinical stem prior to discussion, as not every group will have read every stem.

-

3.

Commitment to action: 5 minutes. Each participant is then asked to write down on a 3×5 card one practical way in which he/she plans to include this coaching paradigm in daily practice. As an option, the facilitator can show the Feedback and Coaching word clouds created at the beginning of the session.

Evaluation

Pre- and postcurricular surveys were developed for the purposes of evaluating this curriculum's impact. The precurricular survey can be administered prior to the workshop (Appendix E for interns and Appendix G for residents). A postcurricular survey that can be administered at the end of the academic year (approximately 12 months later; Appendix F for interns and Appendix H for residents) has been designed to assess the durability of impact.

Results

This curriculum has been implemented in two residency programs to date (the Johns Hopkins internal medicine residency program in September 2014 and the Texoma Medical Center family medicine residency inaugural class in July 2015) and presented at two educational meetings (the 2015 ACGME Annual Education Conference and the 2015 Johns Hopkins Institute for Excellence in Education Annual Education Conference and Celebration). At the education conferences, attendees participated in the interactive workshop, taking the roles of resident and intern.

Survey results for the curriculum were obtained from the Johns Hopkins internal medicine residency program. Fifty-seven house staff participated in the precurricular survey, 50 house staff participated in the interactive workshop, and 39 house staff completed the 12-month postcurricular survey (13 had attended the workshop, and 26 had not). Results from the precurricular survey were intended to describe the culture surrounding feedback prior to implementation. In that survey, 69% of residents reported believing it was important for interns to elicit feedback; however, 51% reported that this never happened. Most house staff reported believing that preparation prior to feedback was important, but 62% of interns and 74% of residents never/rarely prepared. More than half (59%) reported that feedback never/rarely translated into a specific plan of action.

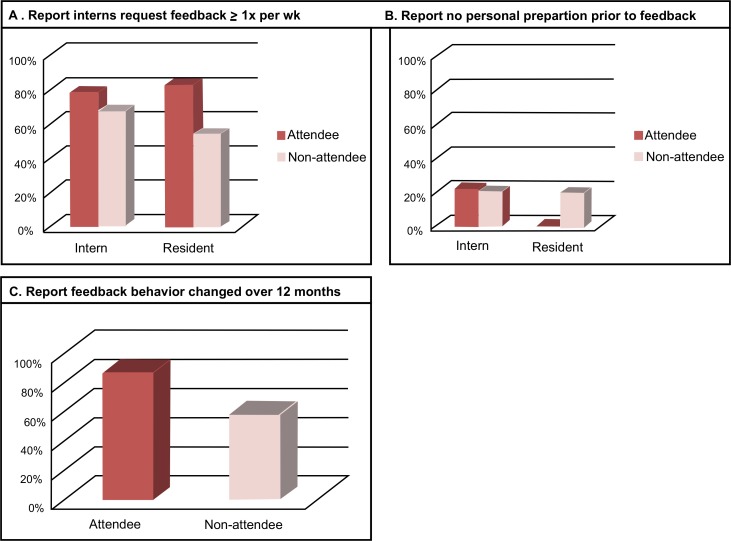

On the postcurricular survey, workshop attendees, as compared to nonattendees, reported greater recognition of interns soliciting feedback; 83% of resident and 78% of intern attendees reported that interns asked for feedback one or more times per week, as compared to 53% of resident and 67% of intern nonattendees (Figure 2A). Preparation did not differ amongst intern attendees versus nonattendees (22% vs. 20%, respectively, reported no preparation) but did differ amongst resident attendees versus nonattendees (0% vs. 19%, respectively, reported no preparation; Figure 2B). Of all house staff (attendees and nonattendees), 43% of interns and 50% of residents reported that feedback rarely/never translated into a specific plan of action. A majority of house staff reported that their feedback behaviors had changed over the course of 12 months (87% of attendees vs. 58% of nonattendees), with most reporting that this change was a result of observing/modeling behavior (67%) or natural improvement with time (62%; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Results of 12-month postcurricular survey. Percentage of survey responders reporting (A) interns request feedback one or more times per week, (B) no personal preparation prior to feedback, and (C) feedback behavior changed over 12 months.

Discussion

During the live sessions convened to date, the concepts of clinical coaching were universally well received, were viewed as applicable across medical disciplines and learning environments, and sparked active conversation about dissatisfaction with current methods of providing and eliciting feedback. The Texoma family medicine residency implemented the curriculum with its inaugural class in July 2015. The program director noted this curriculum was “crucial as our hospital was not a teaching hospital prior to the initiation of the first class.” Furthermore, residents in the Texoma program were observed to be training rotating medical students in the core concepts of clinical coaching.

While the interactive workshop and role-play have appeared successful with each implementation, evaluation of the curriculum's impact is limited by low survey-response numbers. Our 12-month postcurricular survey was sent to all Johns Hopkins internal medicine house staff, regardless of workshop attendance. This allowed for a comparison between attendees and nonattendees with regard to attitudes and behaviors. Attendees reported increased awareness of and preparation for clinical coaching compared to nonattendees. Interestingly, all responding house staff reported changing their feedback behavior over time, although most reported that this change was due to factors other than the coaching curriculum (observation/modeling behavior or maturation as teachers over time). Despite this reported change in feedback behavior, house staff indicated that the critical step of “translate into action” was missing from many feedback interactions. These results highlight the continued need for this curriculum.

Formal evaluation of whether this curriculum impacted knowledge and/or attitudes regarding clinical coaching was accomplished via survey, which had low response rates. Perhaps more important, however, would be to measure the impact of this curriculum on behavior. Direct observation of feedback behaviors is challenging and impractical, given the number of residents and coaches, the frequency with which coaching takes place, and the potential spontaneity of coaching exchanges; arrangements for direct observation therefore could not reasonably be made within the needed time frame for study. Thus, our indirect measure of behavior (asking via survey for self-reported and observed behaviors) seemed the most practical measurement tool. Incentivizing or requiring house staff to complete the evaluation might improve survey responses. Focus-group narrative sessions (e.g., residency exit interviews, clinical competency committee meetings, or yearly meetings with program leadership) might be an additional way to understand the impact of the curriculum.

Our implementation was limited by attendance at house staff conference, a challenge faced by many residencies in the era of duty-hours regulations. Participation could be improved by requiring attendance at this conference or delivering this workshop during a retreat when residents are removed from clinical duties. In the future, we plan to implement this curriculum in such retreat or boot-camp environments—for example, resident retreats, medical student transition to the wards curriculum, and medical student transition to residency curriculum.

The steps proposed in our model provide a strategy for promoting resident-led clinical coaching as a means of contributing to the ongoing assessment and effective feedback that are central to medical education. This curriculum allows residency programs and medical schools to meet the ACGME and LCME standards of providing formal instruction for those who teach. Beyond meeting these standards, this curriculum offers a standardized and streamlined method for strategically incorporating residents into clinical coaching, both for their own benefit and for that of their learners.

Appendices

A. Clinical Coaching Module.wmv

B. Interactive Workshop Presentation.pptx

C. Interactive Workshop Run Sheet.docx

D. Interactive Workshop Role-Play Stems.docx

E. Intern Survey Baseline.docx

F. Intern Survey Postcurriculum.docx

G. Resident Survey Baseline.docx

H. Resident Survey Postcurriculum.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Johns Hopkins Institute for Excellence in Education for its support of this work, as well as for making the video module available online. We would also like to thank Dr. Dave Kern for his educational mentorship.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Informed Consent

All identifiable persons in this resource have granted their permission.

Prior Presentation

Brown L, Rangachari D. Beyond the sandwich: from feedback to coaching. Presented at: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Educators (ACGME) Annual Educational Conference; February 2015; San Diego, CA.

Brown L, Rangachari D, Melia M. Beyond the sandwich: from feedback to coaching. Presented at: Institute for Excellence in Education Summer Teaching Bootcamp, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; July 2015; Baltimore, MD.

Rangachari D, Brown L, Melia M. Beyond the feedback sandwich: from feedback to coaching for residents as teachers. Abstract presented at: Harvard Medical Education Day, Harvard Medical School; October 2015; Boston, MA.

Ethical Approval

This publication contains data obtained from human subjects and received ethical approval.

References

- 1.Bing-You RG, Sproul MS. Medical students’ perceptions of themselves and residents as teachers. Med Teach. 1992;14(2–3):133–138. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421599209079479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post RE, Quattlebaum RG, Benich JJ III. Residents-as-teachers curricula: a critical review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):374–380. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971ffe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block L, Melia M. Residents as teachers curriculum [Johns Hopkins Longitudinal Program in Curriculum Development report]. 2013.

- 4.Common program requirements. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf Published July 2013. Accessed February 23, 2014.

- 5.Functions and structure of a medical school: LCME accreditation standards. Liaison Committee on Medical Education website. http://www.lcme.org/functions.pdf Published May 2012. Accessed October 28, 2013.

- 6.Morrison EH, Friedland JA, Boker J, Rucker L, Hollingshead J, Murata P. Residents-as-teachers training in U.S. residency programs and offices of graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200110001-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janicik R, Schwart M, Kalet A, Zabar S. Residents as teachers. Presented at: General Internal Medicine Faculty Development Meeting; November 30-December 2, 2001; Dallas, TX.

- 8.Milan FB, Parish SJ, Reichgott MJ. A model for educational feedback based on clinical communication skills strategies: beyond the “feedback sandwich.” Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(1):42–47. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1801_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohrenwend A. Serving up the feedback sandwich. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9(10):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delva D, Sargeant J, Miller S, et al. Encouraging residents to seek feedback. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):e1625–e1631. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.806791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Ridder JMM, McGaghie WC, Stokking KM, ten Cate OTJ. Variables that affect the process and outcome of feedback, relevant for medical training: a meta-review. Med Educ. 2015;49(7):658–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burford B, Illing J, Kergon C, Morrow G, Livingston M. User perceptions of multi-source feedback tools for junior doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):165–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil DH, Heins M, Jones PB. Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. J Med Educ. 1984;59(11, pt 1):856–864. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198411000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberman AS, Liberman M, Steinert Y, McLeod P, Meterissian S. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005;27(5):470–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142590500129183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yarris LM, Linden JA, Hern HG, et al. ; for Emergency Medicine Education Research Group (EMERGe). Attending and resident satisfaction with feedback in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(suppl 2):S76–S81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer JC. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med Educ. 2010;44(1):101–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen AR, Wright AS, Kim S, Horvath KD, Calhoun KE. Educational feedback in the operating room: a gap between resident and faculty perceptions. Am J Surg. 2012;204(2):248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogunyemi D, Alexander C, Azziz R, Finke D, Hurley E. Giving feedback (the good and the bad). MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2009;5:7710 http://dx.doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.7710 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tews M, Quinn-Leering K, Fox C, Simonson J, Ellinas E, Lemen P. Residents as educators: giving feedback. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2014;10:9658 http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9658 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aagaard E, Czernik Z, Rossi C, Guiton G. Giving effective feedback: a faculty development online module and workshop. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2010;6:8119 http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.8119 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettit J. Workshop on giving, receiving, and soliciting feedback. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2011;7:9060 http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9060 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariani A, Fromme H, Zegarek M, et al. Asking for feedback: helping learners get the feedback they deserve. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2015;11:10228 http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10228 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fromme H, Mariani A, Zegarek M, et al. Utilizing feedback: helping learners make sense of the feedback they get. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2015;11:10159 http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10159 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Clinical Coaching Module.wmv

B. Interactive Workshop Presentation.pptx

C. Interactive Workshop Run Sheet.docx

D. Interactive Workshop Role-Play Stems.docx

E. Intern Survey Baseline.docx

F. Intern Survey Postcurriculum.docx

G. Resident Survey Baseline.docx

H. Resident Survey Postcurriculum.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.