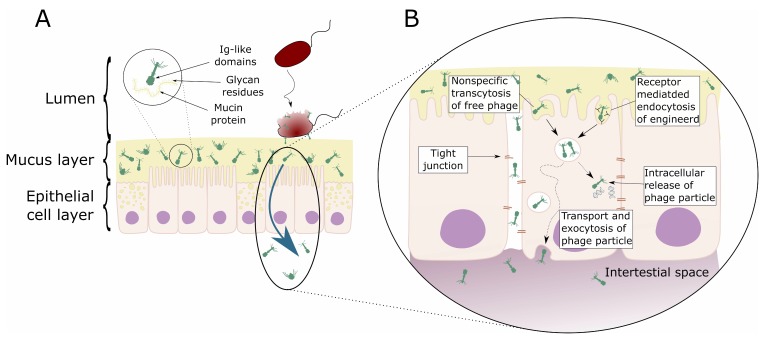

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of direct interaction of phages with mammalian cells. (A) Bacteriophage adhering to mucus (BAM). Mucus is produced by the underlying epithelium. Phages of different morphologies (i.e., Myo-, Sipho-, and Podoviridae) can bind variable glycan residues displayed on mucin glycoproteins through variable capsid proteins, such as Ig-like domains. The adherence of phages to this mucus layer creates an antimicrobial layer that reduces bacterial attachment to and colonization of the mucus. This leads, in turn, to a reduction in epithelial cell death. Furthermore, these phages can migrate through theses epithelial cell layers subsequently ending up in the bloodstream. (B) Phage transcytosis. Binding interactions between phages and the membrane through transmembrane mucins, specific receptors, or through non-specific recognition, may allow signal transduction in the epithelial cell. Subsequently the phage particle is taken up by the epithelial cell. The internalized phage particles may be degraded leading to intracellular release of phage particles and DNA. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that phage particles might cross the eukaryotic cell enabling phages to disseminate to the body. Phages may also gain access to the body via a “leaky gut”, where they bypass the epithelial cell barrier at sites of cellular damage or punctured vasculature. Figure adapted from Barr et al. [63,72].