Abstract

Objective:

Determine the prevalence of benzodiazepine use, including both use as-prescribed and misuse; characterize misuse; determine whether and how misuse varies by age.

Methods:

Cross-sectional analysis of the 2015 and 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults (n=86,186). Measurements included past-year prescription benzodiazepine use and misuse (i.e., use “any way a doctor did not direct”), along with substance use and use disorders, mental illness, and demographic characteristics. Misuse was compared between younger (18–49) and older (≥50) adults.

Results:

30.6 million adults (12.6%) reported past-year benzodiazepine use annually: 25.3 million (10.4%) as-prescribed and 5.3 million (2.2%) with misuse. Misuse accounted for 17.2% of benzodiazepine use overall. Adults 50–64 had the highest prescribed use (12.9%). Those 18–25 had the highest misuse (5.2%), while adults ≥65 had the lowest (0.6%). Misuse and abuse or dependence of prescription stimulants or opioids were strongly associated with benzodiazepine misuse. Misuse without a prescription was the most common type of misuse, while a friend or relative was the most common source. Adults ≥50 were more likely to use a benzodiazepine more often than prescribed and to help with sleep.

Conclusions:

Benzodiazepine use in the U.S. is higher than previously reported and misuse accounted for nearly 20% of use overall. Use among adults 50–64 has now exceeded use by those ≥65. Clinicians should monitor patients also prescribed stimulants or opioids for benzodiazepine misuse. Improved access to behavioral interventions for sleep or anxiety may reduce some misuse.

INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepines are prescribed to over 5% of the U.S. adult population and use is growing (1–3), concentrated among middle-aged adults, for whom use increased nearly 50% from 1996 to 2013 (1). However, benzodiazepine prevalence among adults ≥65 is highest, at 8.6% (1). Prescribing to older adults has been considered potentially inappropriate for decades given associated harms including falls and fractures (4–7), but the growth in benzodiazepine prescribing has been accompanied by growth in related adverse events to adults of all ages. One area of concern has been their combined use with opioids given the increased risk of overdose and overdose death among opioid users co-prescribed benzodiazepines (8–10). But benzodiazepines pose risks of their own: in an analysis of ED visits from 1999 to 2006 for opioid, sedative (i.e., sleep-promoting), or tranquilizer (i.e., anxiolytic or muscle relaxant) poisoning, the largest absolute growth was in benzodiazepine-related poisonings (11), while benzodiazepine-related overdose mortality grew nearly five-fold from 1996 to 2013 (1). Concerns related to benzodiazepine prescribing have spread beyond just older adults or co-prescribing with opioids (12).

The growth in adverse outcomes suggests benzodiazepine prescribing and misuse have increased in tandem, but less is known about benzodiazepine misuse in the U.S. After marijuana use, prescription drug misuse—defined here as use in a manner other than prescribed or by a person to whom it was not prescribed—is the most common type of illicit drug use (13). Most recent benzodiazepine-related work has focused either on misuse in the context of opioid use (14–16) or tranquilizer and/or sedative medication misuse but not benzodiazepines specifically (17, 18). The lack of information about misuse among older adults is particularly striking because they are prescribed benzodiazepines at the highest rates, are most at-risk of related adverse events, and are using alcohol and other substances more than prior cohorts (19, 20). A recent systematic review of benzodiazepine and opioid misuse in older adults (21) found just one study that estimated potential benzodiazepine misuse among older adults in the U.S. (22). Given their widespread use, abuse potential (23), and related risks, surprisingly little is known about benzodiazepine misuse.

Addressing the growing problem of benzodiazepine use and misuse first requires information about the scope and nature of misuse that is occurring. A 2015 redesign of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) now provides detailed information regarding prescription drug use and misuse in the U.S., including the type of and reasons for misuse and the source of the misused medication. We used the redesigned NSDUH to develop national estimates of benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the U.S. and determine whether the characteristics of misuse varied by age, given the unique risks of these medications to older adults and the need for targeted interventions to reduce misuse.

METHODS

This analysis uses NSDUH, which measures the prevalence and correlates of drug use among the U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized population (24). The survey uses a 50-state design with an independent, multistage area probability sample, is administered by RTI International, and sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Respondents complete two computer-assisted segments, one conducted by an interviewer and a second audio-assisted portion without interviewer help, intended to provide a private environment to increase the likelihood of honest reporting of illicit drug use.

NSDUH was redesigned in 2015 to collect more detailed information on the use and misuse of prescription medications, including benzodiazepines—in prior years, questions were limited to misuse exclusively (25). The pre-2015 NSDUH definition of misuse was limited to “nonmedical use”, but the 2015 definition was revised to include “in any way a doctor did not direct.” This analysis is limited to the 2015 and 2016 survey years, the years available post-redesign.

Benzodiazepine Use or Misuse

Respondents could report benzodiazepine use through survey queries regarding tranquilizer or sedative use. NSDUH classifies tranquilizers as medications specifically for relief of anxiety or muscle spasms and sedatives as those for insomnia. This analysis is limited to the 10,290 respondents who specifically reported benzodiazepine use in response to the tranquilizer and sedative items (see online Appendix for additional detail).

For each medication class, NSDUH collected information on past-year use (i.e., taken as prescribed) and misuse. Respondents were asked about the specific manner of misuse: without a prescription; in greater amounts or more often than prescribed; longer than prescribed; or any other use other than as prescribed. Next, they were asked about reasons for misuse: “to relax”, “to experiment”, “to get high”, “for sleep”, “for emotions”, “to counter the effect of another drug”, because they were “hooked”, or another reason. Finally, respondents were asked about the source of medication for misuse (e.g., their clinician or a friend or relative). For this analysis, the misuse category captures a respondent that reported any past-year misuse, even though that respondent may have also used their benzodiazepine as prescribed. Presence of abuse or dependence was determined using criteria from the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).

Other Respondent Characteristics

We included respondent self-rating of health and past-year presence of: a Major Depressive Episode (MDE); suicidal thinking; and mental illness, using a variable developed by NSDUH based on responses to items about psychological distress, functional impairment, symptoms of MDE, and suicidal ideation (26).

We included past-year alcohol, marijuana, and heroin use or abuse/dependence; past-year use of tobacco products; and past-year prescription use, misuse, or abuse/dependence of prescription opioids and stimulants.

Finally, respondents provided sociodemographic information including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and household income.

Analysis

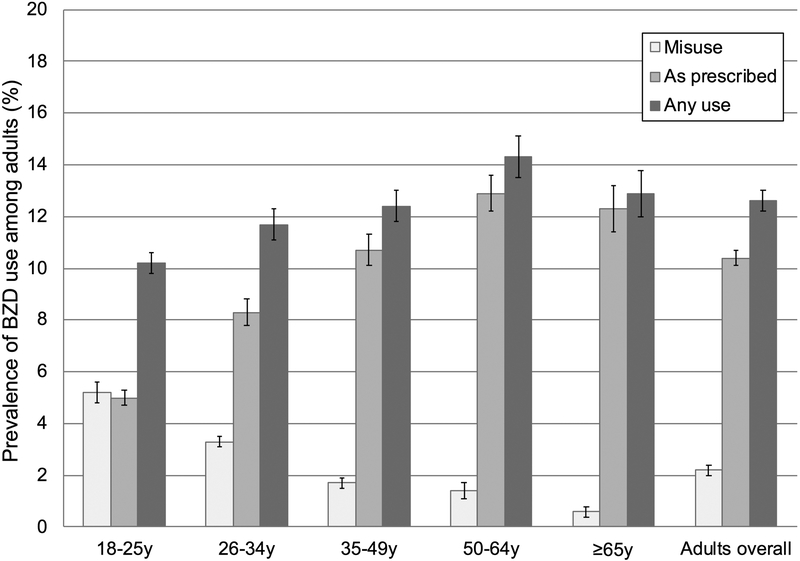

Analyses incorporated weights, clustering, and stratification using NSDUH design elements to account for the complex survey design and generate nationally-representative estimates. After determining population characteristics among adult respondents, we estimated the prevalence of benzodiazepine use—as-prescribed, misuse, and any (Figure 1)—among adults overall and by age group. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics of adults with and without any benzodiazepine use using chi-square tests (Table 1). We determined the magnitude of the association between respondent characteristics and benzodiazepine use using multivariable logistic regression (0 = no benzodiazepine use / 1 = any benzodiazepine use), adjusting for other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Benzodiazepine Prescription Use and Misuse among NSDUH Respondents by Age Group in 2015 and 2016.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Population Overall and Past-year Prevalence and Predictors of Any Benzodiazepine Use

| NSDUH respondents overall (n=86,186) Weighted %a |

BZD use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n=75,896) Weighted % |

Any (n=10,290) Weighted % |

Fb | df | p-value | AORc | 95% CI | ||

| Overall | 100.0 | 87.5 | 12.6 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | 18.2 | 3, 138 | <.001 | |||||

| 18-25 | 14.3 | 89.8 | 10.2 | ref | ||||

| 26-34 | 15.8 | 88.3 | 11.7 | 1.27*** | 1.18-1.36 | |||

| 35-49 | 24.9 | 87.6 | 12.4 | 1.65*** | 1.52-1.78 | |||

| 50-64 | 25.6 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 2.04*** | 1.86-2.22 | |||

| ≥65 | 19.4 | 87.1 | 12.9 | 2.28*** | 2.04-2.54 | |||

| Gender | 366.6 | 1, 50 | <.001 | |||||

| Male | 48.2 | 90.5 | 9.5 | ref | ||||

| Female | 51.8 | 84.6 | 15.4 | 1.84*** | 1.72-1.96 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 221.3 | 3, 124 | <.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 64.6 | 84.6 | 15.4 | ref | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 11.8 | 92.8 | 7.2 | .45*** | .40-.50 | |||

| Hispanic | 15.7 | 92.3 | 7.7 | .59*** | .54-.66 | |||

| Other | 8.0 | 93.5 | 6.5 | .45*** | .38-.53 | |||

| Education | 23.4 | 2, 84 | <.001 | |||||

| <HS | 13.5 | 90.1 | 9.9 | ref | ||||

| HS grad, some college | 56.0 | 86.6 | 13.4 | 1.28*** | 1.12-1.46 | |||

| College grad or higher | 30.4 | 87.8 | 12.2 | 1.41*** | 1.18-1.69 | |||

| Household income | 5.2 | 3, 143 | .002 | |||||

| <$20,000 | 17.4 | 86.2 | 13.8 | ref | ||||

| $20,000-$49,999 | 30.0 | 87.3 | 12.7 | 1.05 | .96-1.15 | |||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 16.3 | 87.9 | 12.1 | 1.05 | .94-1.17 | |||

| ≥$75,000 | 36.3 | 88.0 | 12.0 | 1.12 | .99-1.27 | |||

| Medicaid | 63.6 | 1, 50 | <.001 | |||||

| No | 85.8 | 87.9 | 12.1 | ref | ||||

| Yes | 14.2 | 84.9 | 15.1 | 1.01 | .93-1.11 | |||

| Metropolitan | 12.0 | 2, 94 | <.001 | |||||

| Large | 55.2 | 88.2 | 11.8 | ref | ||||

| Small | 30.0 | 86.5 | 13.5 | 1.02 | .96-1.09 | |||

| Nonmetro | 14.8 | 86.9 | 13.1 | .96 | .87-1.05 | |||

| Past year general health characteristics | ||||||||

| Presence of MDE | 912.5 | 1, 50 | <.001 | n/a | ||||

| No | 93.3 | 89.1 | 10.9 | — | — | |||

| Yes | 6.7 | 66.4 | 33.6 | — | — | |||

| Suicidal ideation | 857.7 | 1, 50 | <.001 | n/a | ||||

| No | 96.0 | 88.3 | 11.7 | — | — | |||

| Yes | 4.0 | 68.6 | 31.4 | — | — | |||

| Presence of mental illness | 215.9 | 2, 98 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 81.9 | 90.9 | 9.1 | ref | ||||

| Mild | 9.2 | 78.5 | 21.5 | 1.93*** | 1.74-2.15 | |||

| Moderate | 4.8 | 70.7 | 29.3 | 2.47*** | 2.20-2.76 | |||

| Severe | 4.2 | 58.5 | 41.5 | 3.80*** | 3.40-4.26 | |||

| Health self-rating | 961.7 | 3, 142 | <.001 | |||||

| Excellent/Very good | 56.8 | 90.2 | 9.8 | ref | ||||

| Good | 29.2 | 86.4 | 13.6 | 1.26*** | 1.16-1.38 | |||

| Fair/Poor | 14.0 | 78.4 | 21.6 | 1.78*** | 1.59-2.00 | |||

| Past year substance use | ||||||||

| Tobacco | 302.1 | 1, 50 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 69.2 | 89.5 | 10.5 | ref | ||||

| Any use | 30.8 | 83.0 | 17.0 | 1.27*** | 1.16-1.38 | |||

| Alcohol | 151.9 | 2, 93 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 30.3 | 89.5 | 10.5 | ref | ||||

| Past year | 63.5 | 87.6 | 12.4 | 1.10* | 1.00-1.21 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 6.2 | 75.9 | 24.1 | 1.53*** | 1.35-1.73 | |||

| Marijuana | 521.5 | 2, 96 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 86.1 | 89.2 | 10.8 | ref | ||||

| Past year | 12.5 | 77.3 | 22.7 | 1.81*** | 1.66-1.98 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 1.4 | 69.7 | 30.3 | 1.97*** | 1.65-2.34 | |||

| Heroin | 292.1 | 2, 96 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 99.6 | 87.6 | 12.4 | ref | ||||

| Past year | .1 | 44.3 | 55.7 | 2.92** | 1.49-5.75 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | .2 | 35.8 | 64.2 | 2.65*** | 1.88-3.74 | |||

| Prescription opioid | 1094.0 | 3, 137 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 63.2 | 93.2 | 6.8 | ref | ||||

| Prescription use | 32.3 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 2.54*** | 2.39-2.71 | |||

| Misuse | 3.8 | 64.5 | 35.5 | 4.21*** | 3.66-4.85 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | .7 | 40.1 | 59.9 | 7.34*** | 5.51-9.76 | |||

| Prescription stimulant | 565.5 | 3, 133 | <.001 | |||||

| None | 93.3 | 88.9 | 11.1 | ref | ||||

| Prescription use | 4.6 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 2.11*** | 1.89-2.36 | |||

| Misuse | 1.9 | 62.6 | 37.4 | 2.71*** | 2.31-3.18 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | .2 | 45.7 | 54.3 | 2.21*** | 1.48-3.29 | |||

NSDUH: National Survey on Drug Use and Health; BZD: benzodiazepine; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; MDE: major depressive episode

This column presents row percentages that reflect characteristics of the U.S. adult population, as estimated by NSDUH (e.g., 14.3% of all adults were age 18-25). Other percentages in table reflect within-row characteristics (e.g., 10.2% of adults age 18-25 reported past-year benzodiazepine use; 89.8% did not). All estimates use NSDUH design elements to generate nationally-representative estimates.

To account for complex survey design, Stata converts the usual Pearson chi square into a F statistic with non-integer degrees of freedom, which have been rounded (https://www.stata.com/manuals13/svysvytabulatetwoway.pdf).

Model is adjusted for all respondent demographic, general health, and substance use characteristics presented as rows in the table. Presence of MDE and suicidal ideation are not included in the model as per NSDUH instructions (26), as those variables are used to generate the Presence of mental illness variable.

p≤.05,

p≤.01,

p≤.001

We then limited analysis to respondents who reported any past-year benzodiazepine use, split into those who reported use as-prescribed or misuse. We compared characteristics of each group using chi-square tests (Table 2). Next, we completed bivariate logistic regression for each characteristic (0 = use as-prescribed / 1 = misuse), including an interaction by age (younger [18–49y] v. older [≥50y]), to determine whether age moderated the association of each characteristic with misuse. We used ≥50 years as the age cutoff because those in later middle age have prescription benzodiazepine use approaching that of adults ≥65 (1), and the youngest respondents in the Baby Boom cohort (i.e., those born in 1964) would have turned 50 just before the 2015 NSDUH. We used multivariable logistic regression to determine the characteristics associated with misuse among benzodiazepine users, adjusting for other demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 2.

Past-year Prevalence of Benzodiazepine Prescription Use and Misuse and Predictors of Benzodiazepine Misuse, Overall and Stratified by Characteristic

| Adults overalla (n=86,186) |

BZD users overalla (n=10,290) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BZD use: as-prescribed (n=7,757) Weighted % |

BZD use: misuse (n=2,533) Weighted % |

BZD use: as-prescribed (n=7,757) Weighted % |

BZD use: misuse (n=2,533) Weighted % |

Fb | df | p-value | AORc | 95% CI | |

| Overall | 10.4 | 2.2 | 82.8 | 17.2 | — | — | |||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||||||

| Age | 188.2 | 3, 139 | <.001 | ||||||

| 18-25 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 49.0 | 51.0 | ref | ||||

| 26-34 | 8.3 | 3.3 | 71.4 | 28.6 | .55** | .46-.66 | |||

| 35-49 | 10.7 | 1.7 | 86.2 | 13.8 | .33** | .27-.41 | |||

| 50-64 | 12.9 | 1.4 | 90.3 | 9.7 | .33** | .26-.43 | |||

| ≥65 | 12.3 | .6 | 95.6 | 4.4 | .23** | .15-.34 | |||

| Gender | 102.3 | 1, 50 | <.001 | ||||||

| Male | 7.3 | 2.3 | 76.3 | 23.7 | ref | ||||

| Female | 13.3 | 2.1 | 86.5 | 13.5 | .74** | .61-.90 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 4.9 | 3, 146 | .003 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 12.9 | 2.5 | 83.6 | 16.4 | ref | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 5.7 | 1.5 | 79.6 | 20.4 | 1.25 | .94-1.65 | |||

| Hispanic | 6.1 | 1.6 | 78.8 | 21.2 | 1.05 | .79-1.38 | |||

| Other | 5.4 | 1.1 | 82.4 | 17.6 | .95 | .67-1.35 | |||

| Education | 9.4 | 2, 100 | <.001 | ||||||

| <HS | 8.1 | 1.9 | 81.3 | 18.7 | ref | ||||

| HS grad, some college | 10.9 | 2.5 | 81.3 | 18.7 | .99 | .77-1.26 | |||

| College grad or higher | 10.5 | 1.7 | 86.2 | 13.8 | .90 | .67-1.22 | |||

| Household income | 9.4 | 3, 140 | <.001 | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 10.9 | 3.0 | 78.6 | 21.4 | ref | ||||

| $20,000-$49,999 | 10.4 | 2.3 | 81.9 | 18.1 | .98 | .79-1.23 | |||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 10.3 | 1.8 | 85.0 | 15.0 | .77 | .58-1.03 | |||

| ≥$75,000 | 10.2 | 1.8 | 84.9 | 15.1 | .84 | .67-1.06 | |||

| Medicaid | 7.0 | 1, 50 | .01 | ||||||

| No | 10.1 | 2.0 | 83.3 | 16.7 | ref | ||||

| Yes | 12.1 | 3.0 | 80.2 | 19.8 | .99 | .79-1.23 | |||

| Metropolitan | 4.8 | 2, 95 | .01 | ||||||

| Large | 9.7 | 2.1 | 82.0 | 18.0 | ref | ||||

| Small | 11.1 | 2.4 | 82.5 | 17.5 | 1.02 | .83-1.25 | |||

| Nonmetrod | 11.3 | 1.8 | 86.0 | 14.0 | .84 | .67-1.06 | |||

| Past year clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Presence of MDE | 20.9 | 1, 50 | <.001 | n/a | |||||

| No | 9.2 | 1.8 | 83.8 | 16.2 | — | — | |||

| Yes | 26.4 | 7.2 | 78.5 | 21.5 | — | — | |||

| Suicidal ideation | 92.9 | 1, 50 | <.001 | n/a | |||||

| No | 9.9 | 1.8 | 84.3 | 15.7 | — | — | |||

| Yes | 21.7 | 9.7 | 69.1 | 30.9 | — | — | |||

| Presence of mental illness | 15.1 | 3, 139 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 7.7 | 1.4 | 84.8 | 15.2 | ref | ||||

| Mild | 18.0 | 3.6 | 83.5 | 16.5 | .90 | .72-1.12 | |||

| Moderate | 22.8 | 6.5 | 77.9 | 22.1 | 1.24 | .93-1.63 | |||

| Severe | 31.7 | 9.8 | 77.3 | 22.7 | 1.19 | .93-1.53 | |||

| Health self-rating | 30.1 | 2, 96 | <.001 | ||||||

| Excellent/Very good | 7.8 | 2.0 | 79.4 | 20.6 | ref | ||||

| Good | 11.2 | 2.4 | 82.7 | 17.3 | .85 | .70-1.04 | |||

| Fair/Poor | 19.2 | 2.3 | 89.2 | 10.8 | .61** | .47-.80 | |||

| Other past-year substance use | |||||||||

| Tobacco | 565.4 | 1, 50 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 9.5 | 1.0 | 90.7 | 9.3 | ref | ||||

| Any usee | 12.3 | 4.8 | 71.9 | 28.1 | 1.41** | 1.17-1.70 | |||

| Alcohol | 199.5 | 2, 90 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 9.8 | .8 | 92.8 | 7.2 | ref | ||||

| Past year | 10.4 | 2.0 | 83.5 | 16.5 | 1.42* | 1.08-1.87 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 13.8 | 10.3 | 57.2 | 42.8 | 2.31** | 1.73-3.09 | |||

| Marijuana | 558.3 | 2, 99 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 9.8 | 1.0 | 90.7 | 9.3 | ref | ||||

| Past yearf | 14.4 | 8.3 | 63.3 | 36.7 | 1.88** | 1.58-2.24 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 11.7 | 18.6 | 38.7 | 61.3 | 2.39** | 1.62-3.52 | |||

| Heroin | 90.3 | 2, 86 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 10.3 | 2.0 | 83.6 | 16.4 | ref | ||||

| Past year | 26.6 | 29.2 | 47.7 | 52.3 | .91 | .41-2.04 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 23.5 | 40.8 | 36.5 | 63.5 | 1.20 | .76-1.91 | |||

| Prescription opioid | 462.0 | 3, 144 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 5.9 | .9 | 86.2 | 13.8 | ref | ||||

| Prescription use | 18.3 | 1.7 | 91.5 | 8.5 | .69** | .57-.84 | |||

| Misuse | 15.6 | 19.9 | 44.1 | 55.9 | 4.11** | 3.26-5.18 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 24.4 | 35.6 | 40.7 | 59.3 | 4.81** | 3.45-6.72 | |||

| Prescription stimulant | 410.6 | 3, 127 | <.001 | ||||||

| None | 9.6 | 1.5 | 86.8 | 13.2 | ref | ||||

| Prescription use | 24.1 | 5.7 | 80.9 | 19.1 | .90 | .74-1.09 | |||

| Misuse | 13.3 | 24.1 | 35.6 | 64.4 | 2.46** | 1.85-3.27 | |||

| Abuse/dependence | 14.7 | 39.6 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 3.40** | 1.72-6.70 | |||

BZD: benzodiazepine; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; MDE: major depressive episode

Under “Adults overall”, a characteristic row presents the prevalence of as-prescribed or misuse within that stratum (e.g., 5.2% of adults 18-25 reported misuse). Under “benzodiazepine users overall”, a row presents the proportion of benzodiazepine use within that stratum that is as-prescribed or misuse (e.g., among adults 18-25, 51.0% benzodiazepine use reported is misuse).

To account for complex survey design, Stata converts the usual Pearson chi square into a F statistic with non-integer degrees of freedom, which have been rounded (https://www.stata.com/manuals13/svysvytabulatetwoway.pdf).

Model is adjusted for all respondent demographic, clinical, and substance use characteristics presented as rows in the table. Presence of MDE and suicidal ideation are not included in the model as per NSDUH instructions (26), as those variables are used to generate the Presence of mental illness variable. Because just 3 of 44 characteristic x age interactions in bivariate tests were statistically significant,d,e,f characteristic-by-age interactions were not included in the adjusted model.

Nonmetro × age interaction in bivariate test p=0.02

Past-year tobacco use × age interaction in bivariate test p=0.002

Past-year marijuana use × age interaction in bivariate test p=0.008

p≤.01,

p≤.001

The final stage of analysis examined the characteristics of past-year benzodiazepine misuse overall and by age (Table 3). We determined the type of, reason for, and source of misused benzodiazepine, along with the specific benzodiazepine misused.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Benzodiazepine Misuse Among Younger and Older Adults

| Respondents with BZD misuse (n=2,533) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Weighted % |

Age 18-49y (n=2,357) Weighted % |

Age ≥50y (n=176) Weighted % |

ORa | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Type of Misuse | ||||||

| Without a prescription | 73.9 | 78.4 | 56.4 | .36 | .25-.51 | <.001 |

| Used in greater amounts than prescribed | 16.0 | 15.0 | 20.2 | 1.44 | .86-2.40 | .16 |

| Used more often than prescribed | 10.1 | 8.1 | 17.9 | 2.47 | 1.57-3.90 | <.001 |

| Used longer than prescribed | 4.9 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 1.24 | .62-2.48 | .53 |

| Used in other ways other than as directed | 18.7 | 17.6 | 23.2 | 1.41 | .90-2.21 | .13 |

| Main reason for misuse | ||||||

| Relax/relieve tension | 47.1 | 48.6 | 41.7 | .76 | .53-1.08 | .12 |

| Experiment | 6.0 | 6.5 | 4.0 | .59 | .21-1.68 | .28 |

| Get high | 11.6 | 13.9 | 3.0 | .19 | .07-.56 | .003 |

| Help with sleep | 26.6 | 22.4 | 41.7 | 2.48 | 1.83-3.35 | <.001 |

| Help with feelings/emotions | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.1 | .86 | .43-1.76 | .68 |

| Increase or decrease effects of another drug | 1.6 | 1.7 | .9 | .51 | .11-2.35 | .38 |

| Hooked or have to have it | .6 | .5 | .9 | 1.89 | .17-20.72 | .60 |

| Source of medication for misuse | ||||||

| 1 clinician | 19.5 | 14.3 | 38.4 | 3.73 | 2.65-5.26 | <.001 |

| ≥2 clinicians | .9 | .6 | 1.9 | 3.27 | .87-12.29 | .08 |

| Stolen from healthcare setting | .1 | .2 | .0 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Free from friend or relative | 53.2 | 55.4 | 45.1 | .66 | .44-.99 | .04 |

| Bought from friend or relative | 12.3 | 14.2 | 5.6 | .35 | .15-.84 | .02 |

| Stolen from friend or relative | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 1.08 | .31-3.81 | .90 |

| Bought from dealer or stranger | 7.7 | 8.9 | 3.1 | .33 | .10-1.07 | .06 |

| Medication of misuse | ||||||

| Alprazolam | 75.1 | 80.3 | 56.4 | .32 | .21-.49 | <.001 |

| Lorazepam | 15.4 | 12.6 | 26.0 | 2.44 | 1.54-3.87 | <.001 |

| Clonazepam | 20.0 | 21.7 | 13.6 | .57 | .33-1.00 | .05 |

| Diazepam | 20.5 | 17.8 | 30.5 | 2.04 | 1.21-3.43 | .009 |

| Other characteristics of BZD misuse | ||||||

| Average days of misuse in past month, mean | 5.4 | 5.0 | 7.1 | 2.10 | −.30-4.51 | .09 |

| Meets past year criteria for abuse (ref: no) | 4.6 | 5.0 | 3.1 | .60 | .20-1.78 | .35 |

| Meets past year criteria for dependence (ref: no) | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.6 | .97 | .50-1.90 | .94 |

BZD: benzodiazepine; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

The odds ratio reports the odds of a specific misuse characteristic (i.e., a table row) among adults ≥50y compared to younger adults (18-49y) as the reference group. For example, the odds of misuse without a prescription among older adults relative to younger adults is .36.

Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) with two-sided tests and α = .05. The XXX Medical School IRB considers analyses of deidentified, publicly-available data exempt from IRB approval.

RESULTS

Prevalence and predictors of any benzodiazepine use

An estimated 30.6 million adults per year in the U.S. (95% confidence interval [CI] = 29.7–31.5 million) reported past-year benzodiazepine use, an overall prevalence of 12.6% (CI=12.2–12.9%), including misuse among 2.2% (CI=2.0–2.3%) and 10.4% as-prescribed (CI=10.1–10.7%). Use among adults 50–64 years was highest (Figure 1; Table 1).

Women and non-Hispanic white respondents reported the highest rates of any past-year use. In the adjusted logistic regression model (Table 1), female gender, older age, and more education were all associated with increased odds of use, while respondent race/ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white was associated with lower odds of any benzodiazepine use.

The presence of past-year mental illness was associated with increased odds of any use, along with worse self-rated health. In almost every instance, past-year use, misuse, or abuse/dependence of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, heroin, prescription opioids, or prescription stimulants were all associated with any benzodiazepine use. Among all substances, prescription opioids were most strongly associated with benzodiazepine use at every level, from use as-prescribed through abuse/dependence.

Prevalence and predictors of benzodiazepine misuse

Among those who reported any benzodiazepine use, 25.3 million (95% CI=24.5–26.1 million) reported use as-prescribed by their clinician, while 5.3 million (CI=5.0–5.6 million) reported misuse. Use as-prescribed was highest among adults 50–64 (Figure 1; Table 2). Misuse was highest among the youngest adults and decreased with age. The majority of benzodiazepine use among respondents 18–25 use misuse, with a prevalence of 5.2% (95% CI=4.8–5.6%). In contrast, misuse was reported by just 0.6% (95% CI=0.4–0.8%) of adults ≥65.

Bivariate logistic regressions testing for a moderating effect of age on the associations between respondent characteristics and misuse found a statistically significant interaction in just 3 instances (Table 2). While age itself was strongly associated with lower odds of misuse, given minimal evidence for a moderating effect, characteristic-by-age interactions were not included in the multivariable model. Females had lower odds of misuse, but, apart from age, no other demographic characteristic was associated with misuse. Fair/poor health self-rating was associated with lower odds of misuse, while any level of marijuana or alcohol use was associated with increased odds of misuse. Prescription opioid use as-prescribed was associated with lower odds of benzodiazepine misuse, while opioid misuse, abuse, or dependence were the characteristics most strongly associated with benzodiazepine misuse.

Characteristics of misuse among younger and older adults

The most common type of benzodiazepine misuse overall was use without a prescription, though this type of misuse use was less likely to be endorsed by respondents ≥50. Relative to younger adults, older respondents were more likely to report using their benzodiazepine more often than prescribed.

The most common reason for misuse overall was to relax or relieve tension, followed by to help with sleep. Older adults were significantly more likely to endorse misuse to help with sleep, while they were much less likely to report misuse to get high.

The most common source of misuse for both age groups was from a friend or relative. When combining all benzodiazepines—free, bought, or stolen—a friend or relative was the source for nearly 70% of respondents reporting misuse. The next-most common source was a single clinician.

Alprazolam was the most common benzodiazepine misused. Relative to younger adults, older adults were more likely to misuse lorazepam or diazepam. Respondents who reported misuse did so on 5.4 days (standard error 0.3 days) in the past month. Among those with misuse, 4.6% (95% CI=3.7–5.6%) and 6.8% (95% CI=5.6–8.2%) met criteria for past-year abuse and dependence, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis of U.S. adults, the annual prevalence of benzodiazepine use, when including both prescription use and misuse, was 12.6% and exceeded 15% among women and non-Hispanic white patients. By age, the highest rate of overall benzodiazepine use was among adults 50–64. More than 2% overall endorsed misuse, which was highest among the youngest adults (18–25), for whom misuse exceeded as-prescribed use. In contrast, at 0.6%, older adults had the lowest prevalence of misuse.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of benzodiazepine use in the U.S. to find that adults ≥65 no longer have the highest prevalence. While use among those ≥65 has not been declining (1, 3), the decades of evidence regarding safety concerns (4, 7, 27) and professional guidelines (6, 28) recommending limited use in older adults may have helped slow growth. In contrast, the aging Baby Boomers—who comprise nearly the entire 50–64 group in this analysis—have higher rates of alcohol and other substance use compared to aging adults before them (19, 20, 29). The high level of use among these late middle-age adults means that potentially inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines to older adults may continue as this cohort ages.

The survey redesign affords new insights into the nature of benzodiazepine misuse, which accounted for nearly 20% of all use among adults but was much more common among younger adults. While age largely did not moderate the patient characteristics associated with misuse, the nature of misuse did vary between younger and older adults. Misuse without a prescription was the most common type of misuse, though this was more common among younger adults; older adults were more likely to use their BZD more often than prescribed. Misuse to help relax and to help sleep were the main reasons for misuse among both age groups, though sleep was a relatively larger driver of misuse among older adults. Relatively little misuse was for experimentation or to get high, and few respondents with benzodiazepine misuse met the criteria for past-year abuse or dependence.

Taken together, these misuse findings raise questions about the underlying contributors to misuse as defined and identified in NSDUH. Younger adults are more likely to lack health insurance (30), while the most common reasons for misuse (e.g., to relax/relieve tension) were all reasons for which a clinician might prescribe a benzodiazepine or refer for behavioral treatment. A significant proportion of the NSDUH-defined “misuse”, therefore, could reflect use for untreated symptoms among those with poor access to care—specifically behavioral treatments for insomnia (31, 32) or anxiety disorders (33, 34). The development of interventions such as web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia may help increase access to benzodiazepine alternatives for those who lack access to providers or insurance or both (35).

Clinicians should recognize their role as a source of misused benzodiazepines, either through medication they prescribed but was used other than as instructed, or as the source of prescribed medication given for misuse to a friend or relative. In addition to being mindful of their role as a potential source for misuse, clinicians have an important role in understanding the reason for their patients’ misuse to determine the appropriate intervention. If patients are consuming prescribed medication faster than expected, why is this the case? Is it for inadequate symptom control? For additional indications (e.g., prescribed for anxiety but also used for sleep)? A patient is allowing another family member to use some? Some misuse may be for symptoms appropriately treated by a benzodiazepine, but clinicians should be mindful of other potential reasons for misuse. An uninsured young relative may use their older relative’s prescribed benzodiazepine for insomnia relieved by a benzodiazepine rather than to get high, but this certainly was not the intention of the prescribing clinician.

Other substance disorders were strongly associated with benzodiazepine use and misuse. Benzodiazepine misuse was most strongly associated with misuse and abuse or dependence of prescription opioids and stimulants. Prescription drug monitoring programs are an important tool for clinicians to understand which of their patients may be misusing other medications and would therefore be at high risk for benzodiazepine misuse. The association of alcohol abuse or dependence with increased odds of benzodiazepine misuse is particularly concerning in light of the increased potential for fatal poisoning when combined (36, 37). This has received much less attention than the opioid-benzodiazepine combination even though alcohol use disorders are more prevalent than prescription opioid use disorders.

Our findings that women, older, and non-Hispanic white respondents had higher use of benzodiazepines is consistent with previous work (1, 2, 39–41). In contrast, women and older patients had lower likelihoods of misuse. This may further support the hypothesis that higher misuse is partially a function of limited access to a prescribed option—limited for younger patients due to lack of insurance and for men due to minimal disclosure of mental health concerns to providers (42). However, higher misuse was not found among racial and ethnic minorities, even though they have limited access to specialty mental health care and lower rates of insurance (30).

Our estimate of the annual prevalence of any benzodiazepine use—12.6% overall and 10.8% as prescribed—is higher than other recent results. A study of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) found 5.6% of adults filled a benzodiazepine prescription in 2013 (1), while a study of the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found benzodiazepine use among 4.2% of adults (43). Survey differences may partially account for the different estimates: NHANES assesses medications from the past 30 days (44), while MEPS samples households, with information often provided by one knowledgeable informant (45). MEPS respondents may underestimate the number of unique medications used in a year, specifically underreporting those used for a shorter duration or with fewer fills (46), which is how benzodiazepines may be prescribed. Finally, NSDUH is the only survey to include misuse. Our estimate of misuse is similar to a NSDUH estimate from 2002–2004 (17), though that analysis examined tranquilizers and sedatives overall and was not limited to benzodiazepines.

Our analysis has a number of limitations. NSDUH is cross-sectional and, due to the 2015 redesign, we cannot track trends in misuse over time. There is the potential for nonresponse bias. NSDUH response rates have been declining, though this is unfortunately true for several federally-administered national surveys (47). NSDUH is nationally-representative, but of the civilian population and therefore does not include active-duty members of the military or institutionalized adults.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of benzodiazepine use among adults in the U.S. is higher than previously reported. While misuse is highest among the youngest adults, overall use among adults 50–64 now exceeds that among those ≥65. At the policy level, more widespread insurance coverage and access to behavioral treatments could potentially reduce benzodiazepine use and misuse, some of which may reflect limited access to a healthcare generally and behavioral treatments specifically. While clinicians should be mindful of the potential for benzodiazepine misuse among patients with any level of substance use, prescription stimulant or opioid use disorders are most strongly associated with benzodiazepine misuse.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

The authors report no competing interests.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R01DA045705).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, et al. : Increasing Benzodiazepine Prescriptions and Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1996–2013. Am J Public Health 106:686–8, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M: Benzodiazepine Use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 72:136–42, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maust DT, Blow FC, Wiechers IR, et al. : National Trends in Antidepressant, Benzodiazepine, and Other Sedative-Hypnotic Treatment of Older Adults in Psychiatric and Primary Care. J Clin Psychiatry 78:e363–e71, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. : Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 169:1952–60, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuck AE, Beers MH, Steiner A, et al. : Inappropriate medication use in community-residing older persons. Arch Intern Med 154:2195–200, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel: American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:2227–46, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Downey W: Benzodiazepines of Long and Short Elimination Half-life and the Risk of Hip Fracture. JAMA 262:3303–7, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, et al. : Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ 350:h2698-h, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, et al. : Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ 356:j760, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ladapo JA, Larochelle MR, Chen A, et al. : Physician Prescribing of Opioids to Patients at Increased Risk of Overdose From Benzodiazepine Use in the United States. JAMA psychiatry 75:623–30, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, et al. : Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Am J Prev Med 38:517–24, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lembke A, Papac J, Humphreys K: Our Other Prescription Drug Problem. N Engl J Med 378:693–5, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipari RN, Williams M, Van Horn SL. Why Do Adults Misuse Prescription Drugs? 2017. July 27 In: The Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Report. Rockville (MD: ): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458284/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calcaterra SL, Severtson SG, Bau GE, et al. : Trends in intentional abuse or misuse of benzodiazepines and opioid analgesics and the associated mortality reported to poison centers across the United States from 2000 to 2014. Clin Toxicol 61:1–8, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouvier BA, Waye KM, Elston B, et al. : Prevalence and correlates of benzodiazepine use and misuse among young adults who use prescription opioids non-medically. Drug Alcohol Depend 183:73–7, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene MS, Chambers RA, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. : Assessment of risk behaviors in patients with opioid prescriptions: A study of indiana’s inspect data. The American journal on addictions 26:822–9, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Desai RA: Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on sedatives and tranquilizers among U.S. adults: psychiatric and socio-demographic correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend 90:280–7, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schepis TS, McCabe SE: Trends in older adult nonmedical prescription drug use prevalence: Results from the 2002–2003 and 2012–2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addict Behav 60:219–22, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blazer DG, Wu L-T: The Epidemiology of Substance Use and Disorders Among Middle Aged and Elderly Community Adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17:237–45, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazer DG, Wu L-T: Nonprescription Use of Pain Relievers by Middle‐Aged and Elderly Community‐Living Adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1252–7, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maree RD, Marcum ZA, Saghafi E, et al. : A Systematic Review of Opioid and Benzodiazepine Misuse in Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24:949–63, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cepeda MS, Fife D, Chow W, et al. : Assessing opioid shopping behaviour: a large cohort study from a medication dispensing database in the US. Drug Saf 35:325–34, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien CP: Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 66:28–33, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017). 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of the Effects of the 2015 NSDUH Questionnaire Redesign: Implications for Data Users. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beers MH: Explicit Criteria for Determining Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use by the Elderly: An Update. Arch Intern Med 157:1531–6, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Geriatrics Society. Ten things physicians and patients should question In: Choosing wisely. ABIM Foundation, 2015. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society/ Accessed August 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soldo B, Mitchell O, Tfaily R, et al. : Cross-Cohort Differences in Health on the Verge of Retirement; in nberorg: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Census Bureau. HI-01: Health Insurance Coverage Status and Type of Coverage by Selected Characteristics. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi/hi-01.html. Accessed August 14, 2018.

- 31.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al. : Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 165:125–33, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buysse DJ, Rush AJ, Reynolds CF: Clinical Management of Insomnia Disorder. JAMA 318:1973–4, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. : Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology 28:403–39, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein MB, Craske MG: Treating Anxiety in 2017. JAMA 318:235, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Ingersoll KS, et al. : Effect of a web-based cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia intervention with 1-year follow-up: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 74:68–75, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka E: Toxicological interactions between alcohol and benzodiazepines. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 40:69–75, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linnoila MI: Benzodiazepines and alcohol. J Psychiatr Res 24:121–7, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford AC, Bradford WD: Medical Marijuana Laws Reduce Prescription Medication Use In Medicare Part D. Health Aff (Millwood) 35:1230–6, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maust DT, Kales HC, Wiechers IR, et al. : No End in Sight: Benzodiazepine Use in Older Adults in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:2546–53, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blazer D, Hybels C, Simonsick E, et al. : Sedative, hypnotic, and antianxiety medication use in an aging cohort over ten years: a racial comparison. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:1073–9, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook B, Creedon T, Wang Y, et al. : Examining racial/ethnic differences in patterns of benzodiazepine prescription and misuse. Drug Alcohol Depend 187:29–34, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, et al. : Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 186:297–301, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Depp CA, et al. : Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines and Nonbenzodiazepine Hypnotics, 1999–2014. Psychiatr Serv 69:235–8, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: 2013–2014 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies (Prescription Medications [RXQ_RX_H]). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/RXQ_RX_H.htm Accessed August 15, 2018.

- 45.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: Frequently Asked Questions. https://meps.ahrq.gov/communication/household_participant_faqs.jsp#7 Accessed August 15, 2018.

- 46.Hill SC, Zuvekas SH, Zodet MW: Implications of the accuracy of MEPS prescription drug data for health services research. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 48:242–59, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Czajka JL, Beyler A (Mathematica Policy Research, Washington, DC). Declining response rates in federal surveys: trends and implications [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2016. June 15 Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255531/Decliningresponserates.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.