Figure 1.

Somite Development

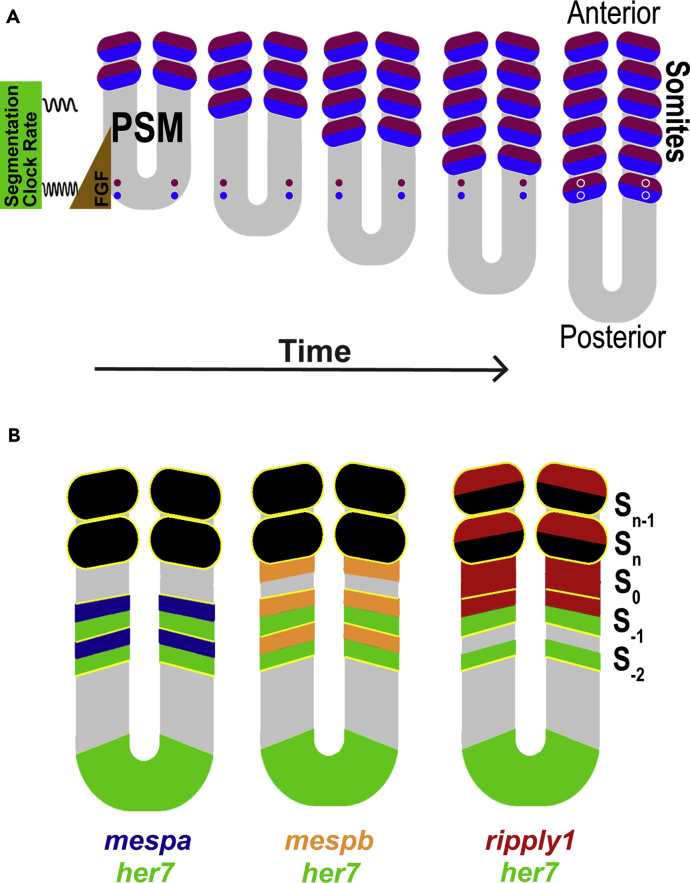

(A) Tracing of a pair of cells destined to become somites. Bilateral somite generation is shown with the differences in final gene expression (purple or blue) based on the phase of the segmentation clock when the cell incorporated into a somite and the movement of a pair of cells into a somite. A pair of cells destined to differentiate into two different tissues derived from a somite is shown as a purple circle and a blue circle. The cells ingress into the tail (posterior) end of PSM through processes of gastrulation and germ layer formation. As more cells enter the posterior PSM, the pair gradually moves anteriorly, eventually reaching the anterior-most boundary of the PSM. The pair of cells then becomes incorporated into a somite (oval). During this trajectory, the cells are exposed to a succession of different signals and express sets of genes in a spatiotemporally ordered manner. High FGF (brown) in the posterior region maintains the cells in an undifferentiated and developmentally plastic state. In the posterior region the segmentation clock oscillates rapidly. As the cells move into the anterior region of the PSM, the oscillation rate decreases and other genes begin to be dynamically expressed. As the cells become established in the posterior compartments of the prospective somite segments, the expression of tissue-specific genes become stable. Because different sets of genes are expressed in cells located in complementary (anterior or posterior) compartments of somites, these cells adopt different fates. The final fate of the cell depends on its phase of oscillation as it exits from the anterior end of PSM. This model is based on Pourquie (2011).

(B) Diagram of the expression domains of clock genes (green), mespaa/mespab (dark blue), mespba/mespbb (orange), and ripply1 genes (dark red). Yellow lines show boundaries of predetermined and formed somites.