Abstract

Background

Europe has experienced a marked increase in the number of children on the move. The evidence on the health risks and needs of migrant children is primarily from North America and Australia.

Objective

To summarise the literature and identify the major knowledge gaps on the health risks and needs of asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children in Europe in the early period after arrival, and the ways in which European health policies respond to these risks and needs.

Design

Literature searches were undertaken in PubMed and EMBASE for studies on migrant child health in Europe from 1 January 2007 to 8 August 2017. The database searches were complemented by hand searches for peer-reviewed papers and grey literature reports.

Results

The health needs of children on the move in Europe are highly heterogeneous and depend on the conditions before travel, during the journey and after arrival in the country of destination. Although the bulk of the recent evidence from Europe is on communicable diseases, the major health risks for this group are in the domain of mental health, where evidence regarding effective interventions is scarce. Health policies across EU and EES member states vary widely, and children on the move in Europe continue to face structural, financial, language and cultural barriers in access to care that affect child healthcare and outcomes.

Conclusions

Asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children in Europe have significant health risks and needs that differ from children in the local population. Major knowledge gaps were identified regarding interventions and policies to treat and to promote the health and well-being of children on the move.

Keywords: children’s rights, general paediatrics

What is already known on this topic?

Europe has experienced a significant increase in migration of displaced people escaping humanitarian crises.

Displaced children are known to be vulnerable to violence, violation of their rights and discrimination.

The existing literature on the health of children on the move in Europe is largely focused on infectious disorders.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child provides children on the move with the right to the conditions that promote optimal health and well-being and with access to healthcare without discrimination.

What this study hopes to add?

Indicates that the main challenges for child health services lie in the domain of mental health and well-being.

Indicates that many children on the move in Europe are insufficiently vaccinated.

Identifies significant gaps in knowledge, particularly with regard to policies and interventions to promote child health and well-being.

Identifies research priorities to promote effective, ethical care and support health policy.

Introduction

Forced displacement is a major child health issue worldwide. More than 13 million children live as refugees or asylum seekers outside their country of birth.2 Conservative estimates suggest that nearly 1 80 000 children on the move are unaccompanied or separated from their caregivers.2 The majority of these children live in Asia, the Middle East and Africa.3

Europe has experienced a marked increase in the number of irregular migrants since 2011, with a peak in arrivals during 2015.4 Children have accounted for a large proportion of people making the journey, either with family or on their own, in search of safety, stability and a better future. Between 2015 and 2017, more than 1 million asylum applications were made for children in Europe.4 The majority of these children originated from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.3 In 2017, 70% of the 210 000 asylum claims made for children in Europe were filed in Germany, France, Greece and Italy.5

The phenomenon of migration to Europe has been characterised by continual evolution, with frequent changes in the most common migration routes, modes of travel and the length of stay in transit countries. Children making these dangerous and often prolonged journeys are exposed to considerable health risks. The health of children on the move is related to their health status before the journey, conditions in transit and after arrival and is influenced by experience of trauma, the health of their caregivers and their ability to access healthcare.6

Much of the literature on the health of children on the move comes from North America and Australia. In light of the marked increase in the number of children arriving in Europe and the need for improved understanding of the situation for these children in the European context, this paper reviews the health risks and needs of children on the move in Europe and how European health policies respond to these risks and needs. It is important to note that children may live for months or years in one or several countries before settling, being repatriated or going underground. In the longer term, factors such as the social determinants of health, ethnicity and issues relating to legal status and prolonged periods of transit begin to take precedence.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) affords all children with the right to healthcare without discrimination.7 Articles 2, 9, 20, 22, 30 and 39 devote specific attention to the rights of displaced and unaccompanied children.7 As such, the CRC provides a useful framework to address the health of children on the move.

Terms such as migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are often used interchangeably and may shift the focus away from people towards political discourse. In this paper, we focus on asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children (table 1). Undocumented children are included because they are known to be a mobile and highly marginalised group, with particular barriers in access to services. We use the term ‘children on the move’ for these three groups of children in order to maintain a rights-based focus.

Table 1.

Definitions

| Child | Person under the age of 18 years.7 |

| Asylum seeker | Persons or children of such persons who are in the process of applying for refugee status under the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention.57 |

| Refugee | A person, who ‘owing to well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinions, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country’.1 |

| Undocumented children | Children who live without a residence permit, have overstayed visas or have refused immigration applications and who have not left the territory of the destination country subsequent to receipt of an expulsion order or children passing through or residing temporarily in a country without seeking asylum.57 |

| Unaccompanied minors | Children who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by any adult.1 |

Methods

The findings presented in this review are based on a comprehensive literature search of studies on the health of children on the move in Europe from 1 January 2007 to 8 August 2017. Searches were run in PubMed and EMBASE on 8 August 2017. Search terms included combinations of terms for children such as ‘child’, ‘youth’ and ‘adolescent’ with terms for migrant, such as ‘migrant’, ‘asylum seeker’, ‘refugee’ and ‘undocumented migrant’ and with terms for countries in the European Union as well as five countries that are major origin and transit countries for children travelling to Europe, including Afghanistan, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey. The database searches were limited to papers providing data on children (birth–18 years) in the English language. Papers were included if they addressed physical and mental health of children on the move, health examinations of these children, the effect of caregiver mental health, access to care or disparities in care between children on the move and the local population. Multiregional reviews that provided data on children in Europe were also included. Papers on adult populations (defined as a study population ≥18 years) that did not provide disaggregated data on children were excluded. However, papers including UASC with a stated age ≤19 years were included, as well as longitudinal cohort studies that followed migrant children into early adulthood (<24 years old). Additional exclusion criteria included special populations, small single-facility studies, lack of migrant and/or health focus, intervention studies that did not provide data on child health outcomes and papers from non-European host countries. Commentaries and conference abstracts were excluded. For further information on specific child health and policy topics, hand searches were also undertaken to identify relevant peer-reviewed papers and grey literature reports.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this study.

Results

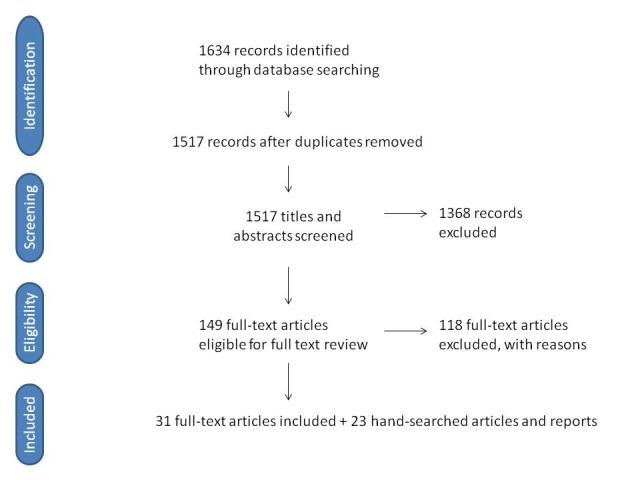

The searches identified 1634 records. After removing 117 duplicates, 1517 titles were screened. A total of 149 papers were reviewed in full text review, of which 118 papers were excluded. Our final sample included 31 papers. An additional 23 articles and reports were identified by the hand searches (figure 1: Flow diagram). Tables 2 and 3 provide an overview of the 45 original research studies and review papers that are included in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Table 2.

Original research articles

| First author and year | Country | Study population | Study design | Sample size (children only) | Summary of findings |

| Huemer et al

41

(2011) |

Austria | African UASC 15–18 years old | Observational cohort | 41 | 56% of African UASC had at least one mental health diagnosis by structured clinical interview. The most common diagnoses were adjustment disorder, PTSD and dysthymia. |

| Derluyn et al

42

(2007) |

Belgium | UASC* | Cross-sectional survey | 142 | Between 37% and 47% of the unaccompanied refugee youths had severe or very severe symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress when screened with the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 37A. Girls and those having experienced many traumatic events are at even higher risk for the development of these emotional problems. |

| Derluyn43

(2008) |

Belgium | Migrant and native adolescents 10–21 years | Cross-sectional survey | 1249 migrant/602 native | Migrant adolescents experienced more traumatic events than their Belgian peers and showed higher levels of peer problems and avoidance symptoms. Non-migrant adolescents demonstrated more symptoms of anxiety, externalising problems and hyperactivity. Factors influencing the prevalence of emotional and behavioural problems were the number of traumatic events experienced, gender and the living situation. |

| Van Berlaer et al

10

(2016) |

Belgium | Asylum seekers | Single facility cross-sectional study | 391 | Primarily reported outcomes in adults. Nearly half of asylum seekers and two-thirds of children<5 years suffered from infections. Among children<5 years, 50% had respiratory diseases (n=76), 20% digestive disorders (n=30), 14% skin disorders (n=21) and 7% suffered from injuries (n=10). |

| Vervliet et al

44

(2014) |

Belgium | UASC 14–17 years old | Longitudinal cohort | 103 | UASC reported an average of 7.5 traumatic experiences at the study start. The mean number of reported daily stressors increased over the study period. Participants had high scores for anxiety, depression and internalising symptoms. There were no significant differences in mental health scores over time. The number of traumatic experiences and the number of daily stressors were associated with significantly higher symptom levels of depression (daily stressors), anxiety and PTSD (traumatic experiences and daily stressors). |

| Hatleberg et al

14

(2014) |

Denmark | Children<15 years old in Denmark | Epidemiological surveillance study | 323 | 323 TB cases were reported in children aged<15 years in Denmark between 2000 and 2009. The incidence of childhood TB declined from 4.1 per 100 000 to 1.9 per 100 000 during the study period. Immigrant children comprised 79.6% of all cases. Among Danish children, the majority were<5 years and had a known TB exposure. Pulmonary TB was the most common presentation. |

| Montgomery38

(2008) |

Denmark | Refugees 11–23 years old | Longitudinal cohort | 131 | Follow-up study in refugee children after 9 years. Participants reported a mean of 1.8 experiences of discrimination. An association was found between discrimination, psychological problems and social adaptation. Perceived discrimination predicted internalising behaviours. Social adaptation was protective, correlating negatively with discrimination as well as externalising and internalising behaviours. |

| Montgomery37

(2010) |

Denmark | Refugees 11–23 years old | Longitudinal cohort | 131 | Same population as Montgomery (2008). On arrival, the children experienced high rates of clinically significant psychological problems which reduced markedly at 9-year follow-up. Persistent symptoms were associated with higher number of types of stressful events after arrival, suggesting environmental factors play an important role in resilience and recovery from psychological trauma. |

| Heudorf et al 20 (2016) | Germany | UASC<18 years old | Observational cohort | 119 | UASC arriving in Frankfurt during October–November 2015 had high levels of drug resistant microbial flora. Enterobacteriaceae with ESBL were detected in 42 of 119 (35%) youth. Nine youth had flora with additional resistance to fluoroquinolones (8% of total screened). |

| Kulla et al 31 (2016) | Germany | Refugee infants and children* rescued at sea | Observational cohort | 293 | Among the 2656 refugees rescued by a German Naval Force frigate between May and September 2015, 19 (0.7 %) were infants and 274 (10.3 %) were children. 27% of all patients required treatment by a physician due to injury or illness and were defined as ‘sick’. One infant (5.2%) and 38 children (13.9%) were identified as sick. Predominant diagnoses were dermatological diseases, internal diseases and trauma. |

| Marquardt et al 11 (2016) | Germany | UASC 12–18 years old | Cross-sectional survey | 102 | Pilot study that employed purpose sampling for a non-representative subset of UASC in Bielefeld, Germany. 59% of the youth had at least one infection and 20% suffered parasitic infections. 13.7% were diagnosed with mental illness. 17.6% were found to have iron deficiency anaemia. Overall, the youth had a low prevalence of non-communicable diseases (<2.0%). |

| Michaelis et al 23 (2017) | Germany | Asylum seekers with Hepatitis A | Epidemiological surveillance study | 231 | Asylum seeking children 5–9 years old accounted for 97 of 278 (35%) reported HAV cases among asylum seekers during September 2015 to March 2016. The predominant subgenotype was 1B, a strain previously reported in the Middle East, Turkey, Pakistan and East Africa. There was one case of transmission from an asymptomatic child to a nursery nurse working in a mass accommodation centre. |

| Mellou et al 24 (2017) | Greece | Refugees, asylum seekers and migrants† living in hosting facilities in Greece | Observational study | 152 | Report on HAV infection among refugees in hosting facilities in Greece April–December 2016. A total of 177 cases were found, of which 152 were in children<15 years old. |

| Pavlopoulou et al 33 (2017) | Greece | Migrant and refugee‡ children 1–14 years old | Single facility prospective cross-sectional study | 300 | Survey of immigrant and refugee children presenting for health examination within 3 months of their arrival, May 2010 and March 2013. The main health problems found included unknown vaccination status (79.3%), elevated blood lead levels (30.6%), dental problems (21.3%), eosinophilia (22.7%) and anaemia (13.7%). Eight children (2.7%) were diagnosed with latent tuberculosis based on Mantoux and chest X-ray and two cases were confirmed with QuantiFERON-TB Gold testing. |

| Ciervo et al 19 (2016) | Italy | Asylum seeking adolescents<18 years | Case series | 3 | Description of Louse-borne relapsing fever in three Somali adolescents who were seeking asylum. |

| Bean et al 45 (2007) | The Netherlands | UASC<18 years old | Prospective cohort study | 582 | The self-reported psychological distress of refugee minors was found to be severe (50%) and of a chronic nature (stable for 1 year) and was confirmed by reports from the guardians (33%) and teachers (36%). The number of self-reported adverse life events was strongly related to the severity of psychological distress. |

| Seglem et al 46 (2011) | Norway | UASC | Cross-sectional survey | 414 | Surveyed of UASC who were granted a residence permit in Norway from 2000 to 2009. The youth ranged from 11 to 27 years at the time of the survey. The study found that UASC are a high-risk group for mental health problems also after resettlement in a new country, with high prevalence of depression and PTSD. |

| Belhassen-Garcia et al 15 (2015) | Spain | Immigrant children and young people†<18 years old | Observational cohort | 373 | Immigrants<18 years of age coming from Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and Latin America were prospectively screened between January 2007 and December 2011. Latent tuberculosis was found in 12.7% (36/285), Active TB infection in 1% (3/285), HBV in 4.3% (15/350) and HCV in 2.35% (8/346). None (0/358) were HIV positive. |

| Bennet16 (2017) | Sweden | UASC<18 years old | Observational cohort | 2422 | 2422 UASC were screened for tuberculosis with a Mantoux tuberculin skin test or a QuantiFERON-TB Gold. 349 had a positive test, of which 16 had TB disease and 278 latent tuberculosis infections (LTBI). Children originating from the horn of Africa had high prevalence of latent TB and TB disease. |

| Hjern et al 39 (2013) | Sweden | Migrant and native 15 year- olds | Cross-sectional survey | 76 229 | In a national survey using the KIDSCREEN instrument, the psychological well-being in foreign-born children from Africa and Asia was found to be much lower (−0.8 in Z-scores) compared with the majority population if the student body consisted mainly of native students from the majority population. Scores were very similar to the majority population in schools where at least 50% had two foreign-born parents. Bullying explained much of this difference. |

| Riddel59 (2016) | Sweden | UASC 9–18 years old | Qualitative interviews | 53 | The youth described experience of extreme violence and exploitation as well as lack of access to physical and mental healthcare. They describe lengthy asylum procedures, delays in receiving a guardian, lack of access to interpreters and inexperienced and inadequately trained staff among guardians in the accommodation centres. Girls and younger children reported being housed with older boys and experiencing bullying and harassment in their accommodation facilities. |

| Alkahtani et al 8 (2014) | England | Refugee children in the East Midlands compared with native controls | Case-control | 117 migrant/99 native | Comparison made between the children of 50 refugee parents (n=117 children) with children of 50 English parents (n=99 children), with median ages 5 and 4 years, respectively. Refugee children were more likely to receive prescribed medicines during the previous month (p=0.008) and 6 months (p<0.001) than English children and were less likely to receive over the counter (OTC) medicines in the past 6 months (p=0.009). The findings suggest financial barrier in access to medication. |

| Bronstein47 (2012) | UK | Afghan UASC 13–18 years | Cross-sectional survey | 222 | One third of youth were found to score above the cut-off on a validated PTSD-screening instrument. |

| Bronstein48 (2013) | UK | Afghan UASC 13–18 years | Cross-sectional survey | 222 | In a survey using the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 37A, 31.4% scored above cut-offs for emotional and behavioural problems, 34.6% for anxiety and 23.4% for depression. Scores increased with time after arrival in the UK and load of premigration traumatic events. |

| Hodes et al 49 (2008) | UK | UASC (13–18 years old) and accompanied refugee children (13–19 years old) | Cross-sectional survey | 78 UASC and 35 accompanied | UASC had experienced high levels of traumatic events (mean of 6.8 events, range 0–16) and reported high levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms compared with accompanied children. Predictors of high posttraumatic symptoms included low-support living arrangements, female gender and experience of trauma. Among UASC, post-traumatic symptoms increased with age. High depressive scores were associated with female gender and region of origin in UASC. |

| Baillot et al 32 (2018) | Multiple | Asylum seekers | Literature review, in-depth interviews with experts in EU-based FGM interventions | N/A | FGM is an important basis for asylum claims girls and women in Europe. Monitoring and interventions vary between countries. There are no pooled data, however, as variations in reporting practices between countries preclude the evaluation or monitoring of FGM-based asylum claims in the EU. |

| Odone et al 18 (2015) | Multiple | Migrants to the EU† | Literature review, analysis of European Surveillance System data and information from experts | N/A | Primarily reported outcomes in adults. From 2000 to 2009, 15.3% of reported paediatric TB cases in the EU/EEA were of foreign origin. This figure is lower than the proportion of foreign-born reported TB cases in the overall population (26%). Norway, Sweden and Austria reported a higher number of foreign-origin TB cases than native-origin TB cases among children<15 years. Risk-based analysis is limited because surveillance data in most EU/EEA countries do not distinguish between children born in the host country to foreign-born parents from those born to native parents. |

| Stubbe Østergaard et al 57 (2017) | Multiple | Asylum seekers and undocumented migrant children<18 years | Survey and desk review | N/A | Surveyed child health professionals, NGOs and European Ombudspersons for Children in 30 EU/EEA countries and Australia and reviewed official documents. Entitlements for asylum seeking, refugee and irregular migrants in the EU are variable; however, only five countries (France, Italy, Norway, Portugal and Spain) explicitly entitle all migrant children, irrespective of legal status, to receive equal healthcare to that of its nationals. The needs of irregular migrants from other EU countries are often overlooked in European healthcare policy. |

| Villadsen et al 30 (2010) | Multiple | Stillbirths and neonatal deaths of infants born to mothers of Turkish origin | Retrospective prevalence study | 239 387 | Includes data from nine EU countries. The stillbirth rates were higher in infants born to Turkish mothers than in the native population in all countries. The neonatal mortality was variable, with elevated risks for infants of Turkish mothers in Denmark, Switzerland, Austria and Germany, and lower rates in Netherlands, the UK and Norway when compared with the native populations. |

| Williams et al 22 (2016) | Multiple | Migrants§ | Literature review, survey of 30 countries, and information from experts | N/A | National surveillance systems do not systematically record migration-specific information. Experts attributed measles outbreaks to low vaccination coverage or particular health or religious beliefs and considered outbreaks related to migration to be infrequent. The literature review and country survey suggested that some measles outbreaks in the EU/EEA were due to suboptimal vaccination coverage in migrant populations. |

| Hjern et al 60 (2017) | EU27 | Migrant children<18 years | Cross-sectional survey to clinicians, national child ombudsmen and NGOs | N/A | Seven EU countries (Belgium, France, Italy, Norway, Portugal and Spain and Sweden) explicitly entitle all non-EU migrant children, irrespective of legal status, to receive equal healthcare to that of its nationals. Twelve European countries have limited entitlements to healthcare for asylum seeking children, including Germany that stands out as the country with the most restrictive healthcare policy for migrant children. The needs of irregular migrants from other EU countries are often overlooked in European healthcare policy. |

*Age groups not clearly defined.

†Migrant status not clearly defined.

‡Immigrants were defined as the children of parents with long- term residence permit who entered Greece for family reunification. The remaining children, including refugees, asylum seekers or irregular migrants were defined as ‘refugees’.

§Variable definitions of migrants between countries and between studies.

ESBL, extended spectrum beta-lactamases; HAV, Hepatitis A Virus; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infections; OTC, over the counter; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TB, tuberculosis.

Table 3.

Review articles

| First author and year | Study population | Study design | Sample size (children only) | Summary of findings |

| Aynsley-Green et al 53 (2012) | Refugee and asylum-seeking children and young people | Review without information on search strategy or inclusion criteria | N/A | Evidence that X-ray examination of bones and teeth is imprecise and unethical and should not be used. Further research needed on a holistic multidisciplinary approach to age assessment. |

| Bollini et al 29 (2009) | Immigrant women(a) who delivered an infant Europe | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 18 322 978 pregnancies in 65 studies | 61 studies were cross-sectional design and 27 were from single facilities. Compared data on 1.6 million in immigrant women with 16.7 million native women. Immigrant women had 43% higher risk of low birth weight, 24% of preterm delivery, 50% of perinatal mortality and 61% of congenital malformations compared with native European women. |

| Cole54 (2015) | UASC | Review article of methods for age assessment | N/A | Most individuals are mature before age 18 in hand-wrist X-rays. On MRI of the wrist and orthopantomogram of the third molar, the mean age of attainment is over 19 years; however, if there is immature appearance, these methods are uninformative about likely age; as such, the MRI and third molars have high specificity but low sensitivity. |

| Derluyn et al 43 (2008) | UASC | Review without information on search strategy or inclusion criteria | N/A | UASC are a vulnerable population with considerable need for psychological support and therefore need a strong and stable reception system. The creation of such a system would be greatly facilitated if the legal system considered them children first and refugees/migrants second. |

| Devi12 (2016) | UASC | Opinion piece | N/A | Summarises findings on infectious diseases affecting unaccompanied minors based on two Unicef and one Human Rights Watch reports. |

| Eiset17 (2017) | Refugees and asylum seekers - all ages | Narrative review | Not specified | 51 studies of infectious conditions in refugees and asylum seekers including children and adults. Findings related to children: limited evidence on infectious diseases among refugee and asylum-seeking children; relatively low vaccination rates with one study showing 52.5% of migrant children needing triple vaccine and 13.2% needing MMR and a further study showing low levels of rubella immunity among refugee children. The review reports on rates of TB, HIV, hepatitis B and C, malaria and less common infections; however, rates are not reported by age group. |

| Fazel et al 35 (2012) | Refugee children and young people | Systematic review | 5776 children and youth in 44 studies | Exposure to violence, both direct and indirect (through parents), are important risk factors for adverse mental health outcomes in refugee children and adolescents. Protective factors include being accompanied by an adult caregiver, experiencing stable settlement and social support in the host country. |

| Hjern55 (in press) | UASC | Narrative review | N/A | Many UASC come from ‘failed states’ like Somalia and Afghanistan where official documents with exact birth dates are rarely issued. No currently available medical method has the accuracy needed to replace such documents. Unclear guidelines and arbitrary practices may lead to alarming shortcomings in the protection of this high-risk group of children and adolescents in Europe. Medical participation, as well as non-participation, in these dubious decisions raises a number of ethical questions. |

| ISSOP Migration Working Group6 (2017) | Migrant children in Europe | Narrative review and position statement | N/A | Based on a comprehensive literature search and a rights-based approach, policy statement identifies magnitude of specific health and social problems affecting migrant children in Europe and recommends action by government and professionals to help every migrant child to achieve their potential to live a happy and healthy life, by preventing disease, providing appropriate medical treatment and supporting social rehabilitation. |

| Markkula et al 9 (2018) | First and second generation migrant children compared with non-migrant children | Systematic review | 10 030 311 children in 93 studies | 57% of included studies were from Europe and 36% from North America. Use of non-emergency healthcare services was less common among migrant compared with non-migrant children: in 19/27 studies reporting on general access to care, 9/19 reporting on vaccine uptake, 9/16 reporting on mental health service use, 9/14 reporting on oral health service use, 10/14 reporting on primary care and other service use. Migrant children were reported to be more likely to use Emergency and Hospital services in 9/15 studies. |

| Mipatrini et al 21 (2017) | Migrants and refugees | Systematic review | N/A | The study reports primarily on data in adults or where age classification is not specified. Overall, migrants and refugees were found to have lower immunisation rates compared with European-born individuals. Studies in migrant children found lower rates of MMR, Polio and tetanus vaccination. Reasons cited include low vaccination coverage in the country of origin and barriers in access to care in Europe. |

| Sauer et al 56 (2016) | UASC | Editorial/Position statement | N/A | Position statement by the European Academy of Paediatrics outlining medical, ethical and legal reasons for recommending that physicians should not participate in age determination of unaccompanied and separated children seeking asylum. |

| Slone36 (2016) | Children aged 0–6 years exposed to war, terrorism or armed conflict | Systematic review | 4365 children in 35 studies | Young children suffer from substantial distress including elevated Risk for PTSD or PTS symptoms, non-specific behavioural and emotional reactions and disturbance of sleep and play rituals. Parental and children’s psychopathology correlated and family environment and parental functioning moderates exposure–outcome association for children. The authors conclude that longitudinal studies are needed to describe the developmental trajectories of exposed children. |

| Williams et al 34 (2016) | Refugee children in Europe | Review without information on search strategy or inclusion criteria | N/A | Increased rates of depression, anxiety disorders and PTSD among refugee children, as well as high levels of dental decay and low immunisation coverage. |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; TB, tuberculosis; UASC, unaccompanied and separated children; FGM, female genital mutilation; NGO, nongovernmental organisation; MMR, Measles, mumps and rubella vaccination.

Overall, the papers indicate that the health needs of children on the move are highly heterogeneous, depending on the conditions in the country of origin, during the journey and after arrival in the countries of destination. Children separated or travelling unaccompanied (UASC) are particularly vulnerable to various forms of exploitation at all phases of their journey and after arrival. Structural, financial, language and cultural barriers in access to healthcare affect care-seeking behaviours as well as diagnostic evaluation, treatment and health outcomes (table 4).6 8 9

Table 4.

Barriers in access to care for children on the move

| Information | Patients and families | Unfamiliar health system, lack of knowledge about where and how to seek care |

| Variable education and literacy, with variable knowledge about health | ||

| Lack of awareness about health rights | ||

| Health professionals | Variable understanding of and experience with treating children on the move | |

| Limited epidemiological data on the health status and context-specific risks of children on the move | ||

| Lack of clear and readily available national guidance on the legal and practical aspects of healthcare for migrants | ||

| Culture and language differences | Language barriers, with limited or lack of access to medical interpreters | |

| Differing cultural and health beliefs | ||

| Expectations for healthcare encounter may differ between the health professional and patient /family | ||

| Financial | Costs associated with care may include transport to health facility, treatment, medications and medical supplies | |

| Other barriers | Distance to health facility, transportation needed to access care | |

| Insufficient time allotted to appointments | ||

| Fear, including the fear that accessing care may affect asylum decision | ||

| Breakdown in trust between patients and health workers | ||

Communicable diseases

During travel and after arrival in Europe, children may be housed in overcrowded facilities with inadequate hygiene and sanitation conditions that place them at risk of communicable diseases. The most common infection sites include the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract and skin, with a concerning prevalence of parasitic and wound infections.10–13

Children originating from low-income and middle-income countries may have been exposed to infectious agents that are rare in high income countries in Europe.14–16 Furthermore, exposure to armed conflict may increase their risk of exposure to infections.17 Notable infections among populations on the move include latent or active tuberculosis (TB),15 18 malaria,17 Hepatitis B and C,15 17 Syphilis,15 Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 or 2,15 louse-born relapsing fever,17 19 shigella17 and leishmaniasis.17 There is a notable lack of studies with age-disaggregated data on HIV prevalence among migrant children in Europe. A Spanish study which screened 358 children did not find any cases.15 While children on the move are at risk for a number of different infections, the prevalence of communicable diseases varies markedly between groups and is thought to be heavily related to the conditions during travel and after migration.17

The treatment of children on the move with infectious diseases may require different regimens than those recommended by national protocols, as these children may be at higher risk of colonisation and infection with drug-resistant organisms. In Germany, routine screening practices at hospital admission have found that children on the move have higher rates of multiple drug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains than the local population.20 MDR Infections may be more difficult to treat and carry higher morbidity and mortality risks.

Children on the move may need catch-up immunisations to match the vaccination schedule of the country of destination.17 Several studies of children on the move in Europe have identified low vaccination coverage against hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella and varicella and low immunity to vaccine preventable diseases including tetanus and diphtheria: this is coupled with a higher prevalence of previous exposure to vaccine-preventable diseases.21 Since 2015, cases of cutaneous diphtheria17 and outbreaks of measles in the EU22 have been attributed to insufficient vaccination coverage in migrant populations. Further, Hepatitis A cases have been reported in children living in camps and centres in Greece and Germany, with particularly high rates among children under 15 years.23 24 There is no evidence of increased transmission of communicable diseases from migrants to host populations.25

Non-communicable diseases and injuries

Displacement places children at risk for a broad variety of non-communicable diseases and injuries that may be exacerbated by limited and irregular access to paediatric and neonatal healthcare. Paediatric groups that are particularly vulnerable include unaccompanied minors, pregnant adolescents and infants.

In 2017, more than half of the children arriving in Europe were registered in Greece, and the largest age group were infants and small children (0–4 years old).26 Infants born during the journey may be born without adequate access to prenatal, intrapartum or postnatal care, resulting in increased birth complications, stillbirth and infant mortality.27 Further, these newborns may have lacked access to screening for congenital disorders that is routinely offered in European countries. Infant nutrition may suffer, particularly as breastfeeding is a challenge for mothers during their journey.28 The evidence regarding the risk of birth complications in children born to mothers after arrival in the destination country is mixed. Some studies in Europe have shown that these infants have higher rates of birth complications, including hypothermia, infections, low birth weight, preterm birth and perinatal mortality when compared with the native population,13 29 while other studies have found that outcomes in certain countries are similar to the national populations.30 These patterns suggest that the cause of altered risks may be related to society-specific factors such as integration policies, socioeconomic disadvantage among different migrant groups and barriers in access to care.30

Traumatic events such as torture, sexual violence or kidnapping may have long‐lasting physical and psychological effects on a child. Physical trauma related to the journey and attempts at illegal border crossings may include skin lacerations, tendon lacerations, fractures and muscle contusions. If left untreated and/or in unhygienic conditions, injuries may become infected, with severe and potentially life-threatening consequences.12 People arriving by sea are particularly susceptible to injury and illness; a recent survey of rescue ships found that dehydration and dermatological conditions associated with poor hygiene and crowded conditions were common, as well as new and old traumatic injuries from both violence and accidents.31 The risk of female genital mutilation is high in girls from certain regions and is a recognised reason for seeking asylum.32

Nutritional deficiencies and dental problems are more common in children on the move, with reported prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia ranging from 4% to 18% among children living in Germany and Greece.11 33 Dental problems are perhaps the most prevalent health issue in children on the move, and indeed caries prevalence has been reported as high as 65% among migrant and refugee children in the UK.34

While the prevalence of non-communicable chronic diseases in children on the move in the EU is not thought to differ significantly from host populations, there is little evidence to support this thinking. Further, the barriers in access to care and different health beliefs pose challenges to diagnosing and managing children on the move with chronic diseases (tables 2 and 3).

Psychosocial and mental health issues

Children on the move are at high risk for psychosocial and mental health problems, with separated and unaccompanied children at highest risk. Direct and indirect exposure to traumatic events are associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and a broad range of internalising and externalising behaviours in refugee children.35

The mental health of caregivers, especially mothers, plays an important role in their children’s mental and physical health. Maternal PTSD and depression are correlated with increased risk of PTSD, PTS symptoms, behavioural problems and somatic complaints in their children.36 Conversely, good caregiver mental health is a protective factor for the mental and behavioural health of refugee children.35

Transit and host country reception policies also impact the mental health outcomes of children on the move. Numerous studies have documented that postmigration detention increases psychological symptoms and the prevalence of psychiatric illness in children on the move.35 Detention, multiple relocations, prolonged asylum processes and lack of child-friendly immigration procedures are associated with poor mental health outcomes in refugee children and have been described in some studies as having placed the children in greater adverse situations than those which the children endured before migration.35 A longitudinal study of refugee children from the Middle East living in Denmark found that psychological symptoms improved over time, with risk factors related to war and persecution being important during the early years after arrival in Denmark.37 In the longer term, social factors in the country of resettlement were more important predictors of mental health.37

Racism and xenophobia play an important role in the psychological health and well-being of children on the move. Studies in Sweden and Denmark have found that the experience of discrimination is common among youth on the move and is associated with lower rates of social acceptance, poorer peer relations and mental health problems.38 39 In a national survey of Swedish 9th graders, rates of bullying experienced by children on the move were associated with migrant density in schools, whereby children attending schools with low migrant density reported three times the rate of bullying compared with those attending schools with high migrant density.39

Unaccompanied minors

The numbers of unaccompanied and separated children seeking asylum in Europe have increased in recent years. During 2015, 95 205, and in 2016, 63 245 UASC applied for asylum in the 28 EU member states, with Germany receiving about a third of these children.40

The mental health of unaccompanied refugee adolescents during the first years of exile has been studied in several European epidemiological studies in recent years.41–50 In the largest of these studies, a comparison was made between three groups2: (1) newly arrived, unaccompanied children aged 12–18 years in the Netherlands,3 (2) young refugees of the same age who had arrived with their parents and4 (3) an age-matched Dutch group.45 The unaccompanied youths had much higher levels of depressive symptoms than the accompanied refugee children (47% vs 27%), and this was partly explained by a higher burden of traumatic stress. Follow-up interviews 12 months later showed no indication of improvement. The level of externalising symptoms and behaviour problems were, however, lower among the unaccompanied refugees than in the Dutch comparison population. A similar picture of high levels of traumatic stress and introverted symptoms was noted in a Norwegian study of 414 unaccompanied youth; of note, this study was carried out at an average of 3.5 years after their arrival in the country.46

Age assessment

Having an assumed chronological age above or below 18 years determines the support provided for young asylum seekers in most European countries, despite the fact that many lack documents with an exact birth date.6 This has led to the use of many different methods to assess age in Europe. In the UK, social workers independent of the migration authorities undertake age assessment interviews which consider any documents or evidence indicating likely age, along with an assessment of appearance and demeanour.51 Many other European countries rely on medical examinations, primarily in the form of radiographs of the hand/wrist (23 countries), collar bone (15 countries) and/or teeth (17 countries).52 The individual variation in age-specific maturity in the later teens with these methods, and the unknown variation between high-income and low-income countries, make them unsuitable for assessing whether a young person is below or above 18 years of age.53 54

The use of these imprecise methods raise serious ethical and human rights concerns and is often experienced as unfair and stressful by the young asylum seekers.55 The European Academy of Paediatrics and several national medical associations have therefore recommended their members not to participate in age assessment procedures of asylum applicants on behalf of the state.56

Health policies and child rights

Identification of the health needs of an individual child on the move, and subsequent timely investigation and management may be suboptimal in the arrival countries for a plethora of reasons associated with legal status, healthcare system efficiencies and individual factors. A recent survey identified 12 EU/EEA countries with significant inequities in healthcare entitlements for children on the move (compared with locally born children) according to their legal status.57 In a number of countries, undocumented children only have access to emergency healthcare services.58 Worryingly, in Sweden, a recent Human Rights Watch report found that children spend months without receiving health screening.59

In an analysis of healthcare policies for children on the move, Hjern et al 60 compared entitlements for asylum seeking and undocumented children in 31 EU member and EES states in 2016 with those of resident children. Only seven countries (Belgium, France, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Sweden) have met the obligations of non-discrimination in the CRC and entitled both these categories of migrants, irrespective of legal status, to receive equal healthcare to that of its nationals. Twelve European countries have limited entitlements to healthcare for asylum seeking children. Germany and Slovakia stand out as the EU countries with the most restrictive healthcare policies for refugee children.

In all but four countries in the EU/EEA, there are systematic health examinations of newly settled migrants of some kind.58 In most eastern European countries and Germany, this health examination is mandatory, while in the rest of western and northern Europe it is voluntary. All countries that have a policy of health examination aim to identify communicable diseases, so as to protect the host population. Almost all countries with a voluntary policy also aim to identify the child’s individual healthcare needs, but this is rarely the case in countries that have a mandatory policy.

Discussion

Our review of the available evidence indicates that children on the move in Europe have particular health risks and needs that differ from both the local population as well as between migrant groups. The body of evidence from Europe remains limited; however, as it is based primarily on observational studies from individual countries, with few multicountry or intervention studies. It is important to note that our searches were limited to studies published in English and listed in the PubMed and EMBASE databases. As such, our searches may have missed relevant studies published in other languages, in the grey literature and studies listed in other databases.

A large body of evidence exists on the health needs and risks of children on the move outside of Europe, most notably in North America and Australia.34 61–64 The evidence from these areas indicates that the health determinants and patterns of risk are similar across settings; the specific health risks and needs of children are heavily dependent on the conditions before and during travel and after arrival. There are also patterns that are shared across high-income, middle-income and low-income settings, such as children’s risk of exposure to violence, risk of exploitation and a high risk of mental health problems related to these two factors.65 The similarities across regions suggest that, although context plays an important role for the individual child, there are certain health risks and needs shared by children on the move across the globe.

In light of these similarities, findings from the literature in other parts of the world may help to fill in some of the existing gaps in the evidence in Europe. For example, there is little good quality evidence from Europe on the risk of injury during the early period after arrival to the country of destination. However, a large Canadian study found that refugee children have an increased risk of injury after resettlement. The study reported a 20% higher rate of unintentional injury in refugee youth compared with non-refugee immigrant youth for most causes of injury, with notably higher rates of motor vehicle injuries, poisonings, suffocation and scald burns.66 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that provide data on the prevalence of disability or its effect on the health and development of children on the move.

There are important contextual factors that are likely to affect the health of children on the move differently across the world. Basic needs such as clean water, sanitation and food security may more profoundly influence child health and well-being in refugee camps in developing countries as compared with Europe. Other contextual factors may include the nature of rights violations, such as the large-scale detention and separation of children on the move from their caregivers in the USA.67 68 Studies in Finnish children separated from their parents for a period during World War II found that these children exhibited altered stress physiology, earlier menarche and lower scores on intelligence testing.69–71 The detention of children together with their families was demonstrated to cause significant, quantifiable harm to children in a comparison study from Australia.72 The interplay between common or widespread health risks, contextual factors, access to care and health promotion activities is likely to play a major role in the ultimate health outcomes of children on the move in a given geographical area.

Newly settled children have greater health needs than the average European child; however, access to healthcare remains a major obstacle for them. Although there have been very few studies assessing access to healthcare by migrant families, it has been proposed that unfamiliar healthcare systems and financial costs of over the counter medications pose specific challenges to the migrant family.8 In the UK, UASC have their specific health needs identified as part of statutory health assessments, where the state has assumed the role of the corporate parent and undertakes the responsibility for the needs of the child. However, accompanied children (those children who arrive with and remain in the care of their migrant, refugee or asylum-seeking parent/s), depend on their newly arrived parent(s) to negotiate unfamiliar healthcare systems.

Other important barriers to care in Europe are similar to those found in other settings, including language barriers, lack of professional medical interpreters and variable cultural competence of health personnel. Health workers may lack knowledge or experience in caring for children on the move, may be unaware of their health rights and may lack guidance on the health needs and risks of the newly arrived population. The International Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health released a position paper characterising these barriers and providing recommendations for health policy, healthcare, research and advocacy.6 These recommendations are grounded in child rights and can serve as a guide for individuals, groups and organisations seeking to improve the health and well-being of children on the move.

The main health risks and the main challenge for health services for children on the move in Europe are in the domain of mental health. A small prospective longitudinal study from Australia identified modifiable protective factors for refugee children’s social and emotional well-being that related to resettlement practices, family factors and community support.73 This review highlights an important knowledge gap in the evidence in Europe for programmes and policies that address early recognition and intervention, access to care and the development of effective preventive services for mental health. There is an urgent need for research on the effect of interventions and policies intended to promote and protect the health, well-being and positive development of children on the move in Europe.

The remarkable resilience observed among displaced children has been a topic of significant discourse and study.6 Healthy and positive adaptive processes have been associated with social inclusion, supportive family environments, good caregiver mental health and positive school experiences.35 74 Although the evidence base for interventions remains limited, research and experience suggest that the most effective way to protect and promote refugee child mental health is through comprehensive psychosocial interventions that address psychological suffering in the context of the child’s family and environment; such interventions necessarily include family, education and community needs and caregiver mental health.75

Conclusion

Asylum seeking, refugee and undocumented children in Europe have significant health risks and needs that differ between groups and from children in the local population. Health policies across EU and EES member states vary widely, and children on the move in Europe face a broad range of barriers in access to care. The CRC provides children with the right to access to healthcare without discrimination and to the conditions that promote optimal health and well-being. With children increasingly on the move, it is imperative that individuals and sectors that meet and work with these children are aware of their health risks and needs and are equipped to respond to them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ISSOP Migration Working Group, whose work inspired this review paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors collectively identified the need for the paper. AK designed and carried out the database searches. NS, AH and AK screened titles and abstracts, and all authors screened full text papers. AK, AB and AH wrote sections of the first draft. AK led development and compilation of the first draft and carried out subsequent revisions. All authors contributed to critical review of the drafts and to the development of the supporting tables and figures.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. IOM. International migration law: glossary on migration. 2004. (Accessed 16 Mar 2017).

- 2. UNHCR. Global trends: forced displacement in 2017: Geneva; UNHCR, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF. Uprooted: the growing crisis for refugee and migrant children: UNICEF, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. EUROSTAT. Asylum statistics explained: 2017. 2018. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Asylum_statistics (Accessed 13 Oct 2018).

- 5. UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM. Refugee and Migrant Children in Europe: overview of trends 2017: UNICEF, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. ISSOP Migration Working Group. ISSOP position statement on migrant child health. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:161–70. 10.1111/cch.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Human Rights. Convention on the rights of the child. 1989.

- 8. Alkahtani S, Cherrill J, Millward C, et al. . Access to medicines by child refugees in the East Midlands region of England: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006421 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Markkula N, Cabieses B, Lehti V, et al. . Use of health services among international migrant children - a systematic review. Global Health 2018;14:52 10.1186/s12992-018-0370-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Berlaer G, Bohle Carbonell F, Manantsoa S, et al. . A refugee camp in the centre of Europe: clinical characteristics of asylum seekers arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013963 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marquardt L, Krämer A, Fischer F, et al. . Health status and disease burden of unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents in Bielefeld, Germany: cross-sectional pilot study. Trop Med Int Health 2016;21:210–8. 10.1111/tmi.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Devi S. Unaccompanied migrant children at risk across Europe. Lancet 2016;387:2590 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30891-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Noori T. Assessing the burden of key infectious diseases affecting migrant populations in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hatleberg CI, Prahl JB, Rasmussen JN, et al. . A review of paediatric tuberculosis in Denmark: 10-year trend, 2000-2009. Eur Respir J 2014;43:863–71. 10.1183/09031936.00059913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belhassen-García M, Pérez Del Villar L, Pardo-Lledias J, et al. . Imported transmissible diseases in minors coming to Spain from low-income areas. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:370.e5–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bennet R, Eriksson M. Tuberculosis infection and disease in the 2015 cohort of unaccompanied minors seeking asylum in Northern Stockholm, Sweden. Infect Dis 2017;49:501–6. 10.1080/23744235.2017.1292540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eiset AH, Wejse C. Review of infectious diseases in refugees and asylum seekers-current status and going forward. Public Health Rev 2017;38:22 10.1186/s40985-017-0065-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Odone A, Tillmann T, Sandgren A, et al. . Tuberculosis among migrant populations in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:506–12. 10.1093/eurpub/cku208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ciervo A, Mancini F, di Bernardo F, et al. . Louseborne relapsing fever in young migrants, Sicily, Italy, July-September 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:152–3. 10.3201/eid2201.151580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heudorf U, Krackhardt B, Karathana M, et al. . Multidrug-resistant bacteria in unaccompanied refugee minors arriving in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, October to November 2015. Euro Surveill 2016;21 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.2.30109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mipatrini D, Stefanelli P, Severoni S, et al. . Vaccinations in migrants and refugees: a challenge for European health systems. A systematic review of current scientific evidence. Pathog Glob Health 2017;111:59–68. 10.1080/20477724.2017.1281374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams GA, Bacci S, Shadwick R, et al. . Measles among migrants in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:6–13. 10.1177/1403494815610182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michaelis K, Wenzel JJ, Stark K, et al. . Hepatitis A virus infections and outbreaks in asylum seekers arriving to Germany, September 2015 to March 2016. Emerg Microbes Infect 2017;6:e26 10.1038/emi.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mellou K, Chrisostomou A, Sideroglou T, et al. . Hepatitis a among refugees, asylum seekers and migrants living in hosting facilities, Greece, April to December 2016. Euro Surveill 2017;22:30448 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.4.30448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization. Migration and communicable diseases: no systematic association. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. UNICEF. Refugee and migrant crisis in europe: humanitarian situation report. 28. https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/sitreprandm.pdf.

- 27. Keygnaert I, Ivanova O, Guieu A, et al. . What is the evidence on the reduction of inequalities in accessibility and quality of maternal health care delivery for migrants? A review of the existing evidence in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. IOM, UNICEF. Data brief: migration of children to Europe. 2015. http://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/press_release/file/IOM-UNICEF-Data-Brief-Refugee-and-Migrant-Crisis-in-Europe-30.11.15.pdf (Accessed 5 December 2016).

- 29. Bollini P, Pampallona S, Wanner P, et al. . Pregnancy outcome of migrant women and integration policy: a systematic review of the international literature. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:452–61. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villadsen SF, Sievers E, Andersen AM, et al. . Cross-country variation in stillbirth and neonatal mortality in offspring of Turkish migrants in northern Europe. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:530–5. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kulla M, Josse F, Stierholz M, et al. . Initial assessment and treatment of refugees in the Mediterranean Sea (a secondary data analysis concerning the initial assessment and treatment of 2656 refugees rescued from distress at sea in support of the EUNAVFOR MED relief mission of the EU). Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016;24:75 10.1186/s13049-016-0270-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baillot H, Murray N, Connelly E, et al. . Addressing female genital mutilation in Europe: a scoping review of approaches to participation, prevention, protection, and provision of services. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:21 10.1186/s12939-017-0713-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pavlopoulou ID, Tanaka M, Dikalioti S, et al. . Clinical and laboratory evaluation of new immigrant and refugee children arriving in Greece. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:132 10.1186/s12887-017-0888-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams B, Cassar C, Siggers G, et al. . Medical and social issues of child refugees in Europe. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:839–42. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, et al. . Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012;379:266–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Slone M, Mann S. Effects of war, terrorism and armed conflict on young children: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2016;47:950–65. 10.1007/s10578-016-0626-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Montgomery E. Trauma and resilience in young refugees: a 9-year follow-up study. Dev Psychopathol 2010;22:477–89. 10.1017/S0954579410000180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Montgomery E, Foldspang A. Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. Eur J Public Health 2008;18:156–61. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hjern A, Rajmil L, Bergström M, et al. . Migrant density and well-being-a national school survey of 15-year-olds in Sweden. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:823–8. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. EUROSTAT. Asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors. 2017. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=migr_asyunaa&lang=en (Accessed 19 Nov 2018).

- 41. Huemer J, Karnik N, Voelkl-Kernstock S, et al. . Psychopathology in African unaccompanied refugee minors in Austria. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2011;42:307–19. 10.1007/s10578-011-0219-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Derluyn I, Broekaert E. Different perspectives on emotional and behavioural problems in unaccompanied refugee children and adolescents. Ethn Health 2007;12:141–62. 10.1080/13557850601002296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Derluyn I, Broekaert E. Unaccompanied refugee children and adolescents: the glaring contrast between a legal and a psychological perspective. Int J Law Psychiatry 2008;31:319–30. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vervliet M, Lammertyn J, Broekaert E, et al. . Longitudinal follow-up of the mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23:337–46. 10.1007/s00787-013-0463-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bean TM, Eurelings-Bontekoe E, Spinhoven P. Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: one year follow-up. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1204–15. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seglem KB, Oppedal B, Raeder S. Predictors of depressive symptoms among resettled unaccompanied refugee minors. Scand J Psychol 2011;52:457–64. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bronstein I, Montgomery P, Dobrowolski S. PTSD in asylum-seeking male adolescents from Afghanistan. J Trauma Stress 2012;25:551–7. 10.1002/jts.21740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bronstein I, Montgomery P, Ott E. Emotional and behavioural problems amongst Afghan unaccompanied asylum-seeking children: results from a large-scale cross-sectional study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;22:285–94. 10.1007/s00787-012-0344-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hodes M, Jagdev D, Chandra N, et al. . Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum seeking adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;49:723–32. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Derluyn I, Broekaert E, Schuyten G. Emotional and behavioural problems in migrant adolescents in Belgium. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;17:54–62. 10.1007/s00787-007-0636-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Busler D, Cowell K, Johnson H, et al. . Age assessment guidance: guidance to assist social workers and their managers in undertaking age assessments in England. Association of directors of children’s services. 2015. http://adcs.org.uk/assets/documentation/Age_Assessment_Guidance_2015_Final.pdf (Accessed 13 October 2018).

- 52. European Asylum Support Office. European asylum support office. Age assessment practice in Europe. 2014. https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/public/EASO-Age-assessment-practice-in-Europe1.pdf (Accessed 1 March 2017).

- 53. Aynsley-Green A, Cole TJ, Crawley H, et al. . Medical, statistical, ethical and human rights considerations in the assessment of age in children and young people subject to immigration control. Br Med Bull 2012;102:17–42. 10.1093/bmb/lds014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cole TJ. The evidential value of developmental age imaging for assessing age of majority. Ann Hum Biol 2015;42:379–88. 10.3109/03014460.2015.1031826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hjern A, Ascher H, Vervliet M. Age assessment of young asylum seekers – science or deterrence? Semovilla D, Handbook of research with unaccompanied children. edn: In press. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sauer PJ, Nicholson A, Neubauer D. Advocacy and ethics group of the European Academy of Paediatrics. Age determination in asylum seekers: physicians should not be implicated. European Journal of Pediatrics 2016;175:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stubbe Østergaard L, Norredam M, Mock-Munoz de Luna C, et al. . Restricted health care entitlements for child migrants in Europe and Australia. Eur J Public Health 2017;27:869–73. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hjern A, Stubbe-Østergaard L. Migrant children in Europe: entitlements to health care. London: EU Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Riddell R. Seeking refuge: unaccompanied childre in Sweden: Human Rights Watch, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hjern A, Østergaard LS, Norredam M, et al. . Health policies for migrant children in Europe and Australia. The Lancet 2017;389:249 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chilton LA, Handal GA, Paz-Soldan GJ. Council on community pediatrics. providing care for immigrant, migrant, and border children. Pediatrics 2013;131:e2028–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. . Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2011;183:E824–925. 10.1503/cmaj.090313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Foundation House. Promoting refugee health: a guide for doctors, nurses and other health care providers caring for people from refugee backgrounds. 3rd edn Melbourne: Foundation House, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zwi K, Woodland L, Mares S, et al. . Helping refugee children thrive: what we know and where to next. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:529–32. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reed RV, Fazel M, Jones L, et al. . Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012;379:250–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60050-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saunders NR, Macpherson A, Guan J, et al. . Unintentional injuries among refugee and immigrant children and youth in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cross-sectional study. Inj Prev 2018;24:337–43. 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Linton JM, Griffin M, Shapiro AJ. Detention of immigrant children. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20170483 10.1542/peds.2017-0483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kraft C. AAP Statement on executive order on family separation: American academy of pediatrics. 2018. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/AAP-Statement-on-Executive-Order-on-Family-Separation.aspx (Accessed 8 Oct 2018).

- 69. Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Feldt K, et al. . Childhood separation experience predicts HPA axis hormonal responses in late adulthood: a natural experiment of World War II. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010;35:758–67. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, et al. . Reproductive traits following a parent-child separation trauma during childhood: a natural experiment during World War II. Am J Hum Biol 2008;20:345–51. 10.1002/ajhb.20735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pesonen A-K, Räikkönen K, Kajantie E, et al. . Intellectual ability in young men separated temporarily from their parents in childhood. Intelligence 2011;39:335–41. 10.1016/j.intell.2011.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zwi K, Mares S, Nathanson D, et al. . The impact of detention on the social-emotional wellbeing of children seeking asylum: a comparison with community-based children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:411–22. 10.1007/s00787-017-1082-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zwi K, Woodland L, Williams K, et al. . Protective factors for social-emotional well-being of refugee children in the first three years of settlement in Australia. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:261–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008;20:317–28. 10.1080/09540260802090363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fazel M, Betancourt TS. Preventive mental health interventions for refugee children and adolescents in high-income settings. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:121–32. 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30147-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.