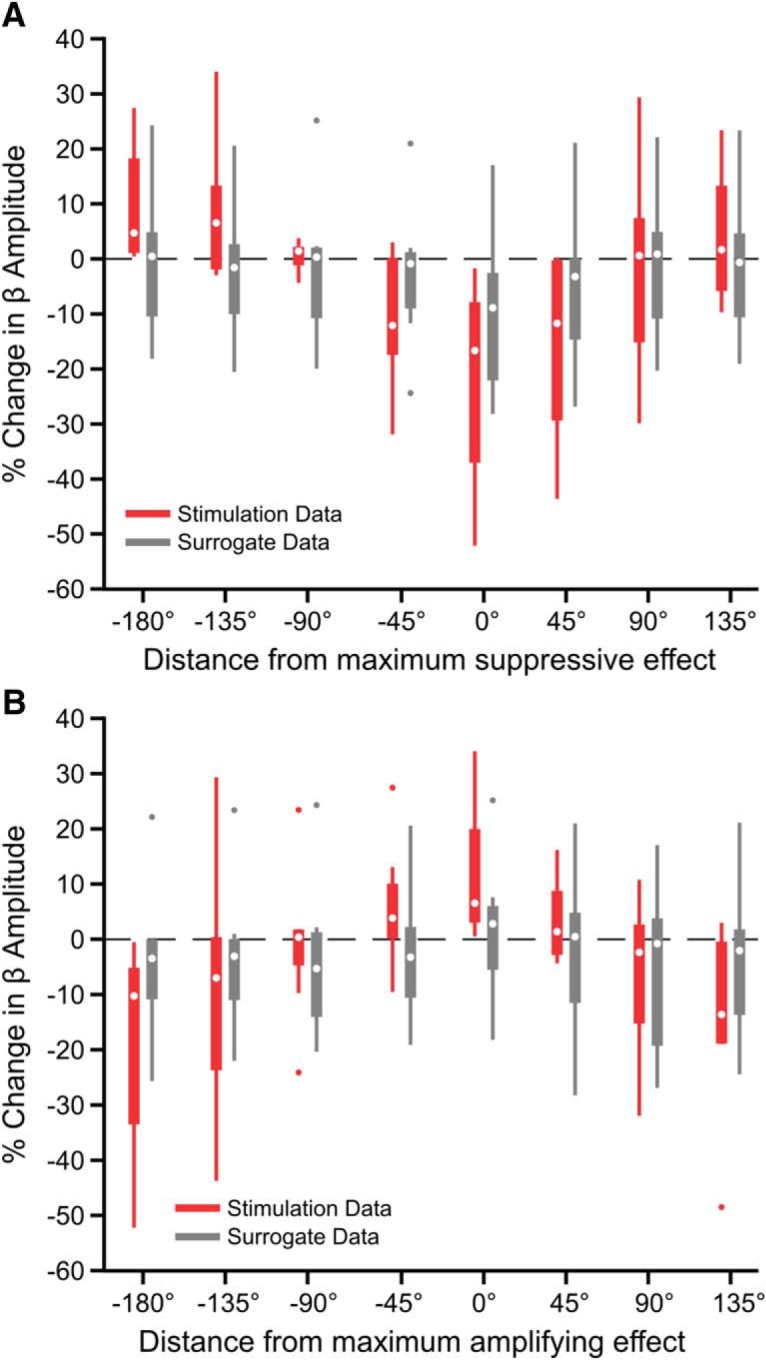

Figure 3.

Phase-dependent effects of single stimuli on beta amplitude did not exceed variability of the unstimulated LFP. Without taking into consideration the phase of past stimuli, phase-dependent effects of stimulation on beta amplitude (red) did not exceed effects seen using a time-matched unstimulated portion of the data sampled at the stimulation frequency (gray) across eight patients. All stimulus pulses were grouped into eight overlapping phase bins, ¼ of a cycle wide. Phase-dependent effects of stimulation on beta amplitude were seen when phase bins were aligned (A) to the bin showing the maximum beta suppression for each patient (χ2 = 28.74, p = 0.0002, Kruskal–Wallis test) as well as (B) to the bin showing the maximum amplifying effect for each patient. Surrogates did not show a significant phase-dependent trend for either (A; χ2 = 4.9, p = 0.673, Kruskal–Wallis test or (B; χ2 = 3.39, p = 0.847, Kruskal–Wallis test). However, stimulus-induced modulation of the beta amplitude was not significantly different from modulation seen using surrogates for any phase bin in either alignment (p > 0.05, Wilcoxon ranked sum test). Data are shown using a boxplot where the central dot is the median and box edges are the 25th and 75th percentiles. Outliers are plotted individually and defined as outside q75 − w * (q75 − q25) and q25 + w * (q75 − q25) where q25 and q75 are the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and w is the maximum whisker length.