There has been a rapid progression in the development of nanomaterials, such as nanowires, nanotubes, nanoparticles, and nanocrystals, which have showed superior electronic, magnetic, optical, and mechanical properties that may not be obtained in their bulk states. These materials are extremely attractive as future building blocks in various applications such as electronics, sensors, catalysis, magnetic storage, drug delivery, tissue engineering, ion channels, and medical imaging as their physical and chemical properties are tunable via size and shape control.[1–10] While the development of these nanometer-scale devices is getting closer to industrial applications, there are still problems in the bottom-up processing of these nanomaterials. For example, the assembly of those nanomaterials at exact locations and directions to develop certain device configurations is not an easy task. The alignment of nanowires and nanotubes on substrates has been achieved by microfluidics,[11] electric and magnetic fields,[12–15] direct mechanical transfer,[16] and hydrophobic interactions;[17] however, more robust, highly selective, and simpler techniques are desirable to assemble nanomaterials onto their targeted locations.

In nature, biological nanomaterials are routinely synthesized under ambient conditions in microscopic-sized laboratories such as cells. Peptides and proteins can undergo self-assembly processes in vivo and in vitro and they are assembled into various nanometer-scale structures, such as nanoparticles, nanotubes, and nanowires at room temperature via their molecular-recognition functions.[18–22] Applications of molecular recognition in nanofabrication have been reported where DNA and peptide nanowires were immobilized at desired locations.[20,23–28] The smart recognition function of proteins can also address biological nanomaterials to exact locations in the cells.[29,30] While the molecular recognition-driven assemblies of these biological nanowires have been examined, there has been, to our knowledge, no report to statistically evaluate the efficiency and the accuracy of the attachment of antibody-coated nanomaterials on complementary antigen-patterned surfaces. This information may have a broad impact on the application of biomaterials in device fabrications as misalignments and misplacements of nanotubes need to be reduced significantly in order to transfer this technology to practical manufacturing. Here we applied the antibody–antigen recognition functions to assemble antibody-functionalized nanotubes at specific locations on substrates where their complementary proteins were patterned, and the yield of the nanotube attachment was increased by maximizing the antibody–antigen interaction (Figure 1).

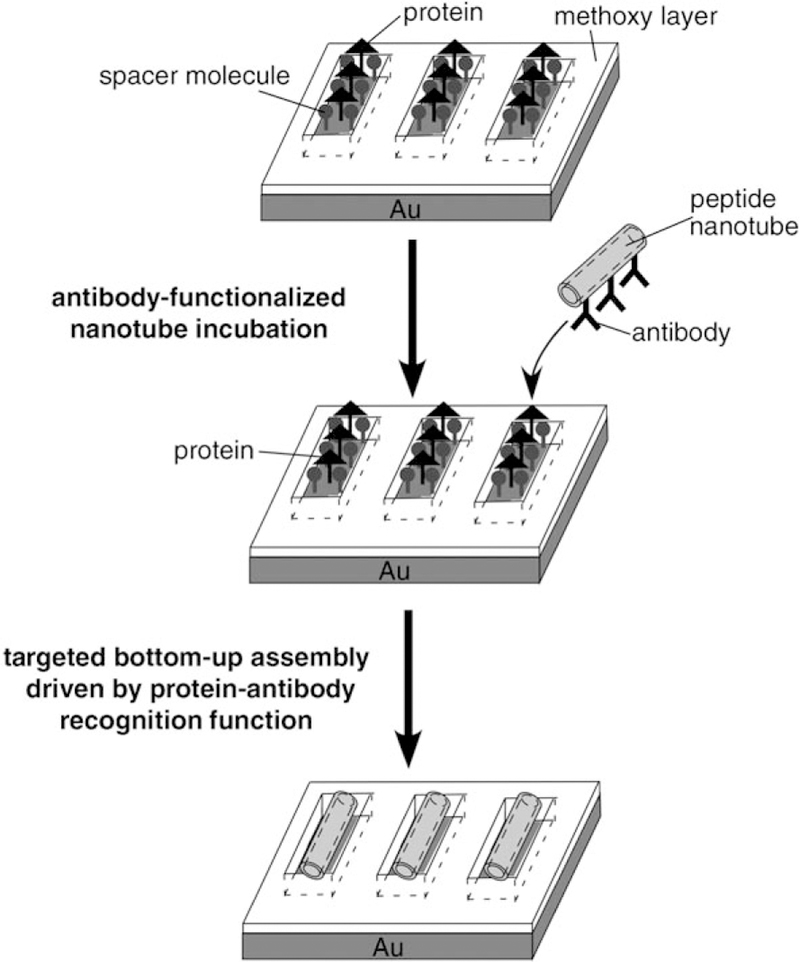

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for the assembly of antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes onto their antigen-patterned substrates via biological recognition. After trenches were shaved on the methooxythiol SAMs by using the AFM tip, and human-IgG and spacer molecules were deposited on the shaved trenches, antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes were immobilized onto the human-IgG-coated trenches via biological recognition.

In this fabrication, antibody-coated nanotubes were fabricated by coating antibodies on template peptide nanotubes, self-assembled from bolaamphiphile peptide monomers, bis(N-α-amido-glycylglycine)-1,7-heptane dicarboxylate,[31,32] which anchored the antibodies on the amide groups of the nanotube surface via hydrogen bonding.[33,34] The protein-patterned substrates were fabricated in two steps; first an array of trenches was written by shaving self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of 17-methoxyheptadecane-1-thiol on Au substrates with the tip of an atomic force microscope (AFM), and then the proteins were assembled on the shaved areas by thiol–Au interactions.[20,35] To achieve the most accurate positioning of the antibody-coated nanotubes on the complementary antigen-patterned trenches, we maximized the antibody–antigen interaction by optimizing the density and conformation of the antigen in the trenches.

The theory of maximizing the antibody–antigen interactions between nanoscale surfaces can be explained as follows. There is always an optimal surface coverage of ligand for which the ligand–acceptor binding percentage is maximal[36,37] due to the competition between the repulsive entropy between binding proteins and the attractive enthalpy between proteins and ligands.[38] As illustrated in Figure 2a, at high ligand concentration on the surface, the repulsive interaction between the bound proteins increases with increasing protein concentration on the surface.[36] However, the positive effect of the binding energy between proteins and ligands gets the upper hand over the repulsive energy when the distance between ligands increases by diluting and by spacing them out with inert molecules on the surface (Figure 2b). Under these conditions, the ligands also gain more degrees of freedom in their orientation, which increases the attractive force between proteins and ligands.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the correlation between the binding affinity of the ligand–protein on surfaces and the concentration of ligands based on the lateral repulsive interaction between proteins and the protein–ligand attractive interaction at a) high ligand concentrations and b) low ligand concentrations.

In this work, we optimized the concentrations of proteins on the surface to achieve the maximum affinity between the proteins on the surface and the antibodies on the nanotubes, which ultimately enabled us to immobilize nanomaterials at targeted locations with high accuracy. The concentration of human gamma immunoglobulin (IgG) on 150 nm× 600 nm trenches, fabricated as 5 × 3 arrays, was controlled by diluting the IgG monolayers with inert spacers, namely bovine serum albumin (BSA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG), and the attachment % of antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes onto those substrates was studied. Overall, we examined 300 trenches for each IgG concentration to obtain statistical data for the attachment % of the antibody-coated nanotubes on those trenches. Figure 3a shows a representative AFM image of the 5 × 3 trench before incubating the antibody-coated nanotubes. The array of dark bars in this image shows the positions of the trenches, whose heights are lower than the SAM/Au substrate. When the concentration of the human IgG was 70% with 30 % of BSA spacer on the trench, very few antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes could be attached to those trenches, as shown in Figure 3b. However, when the concentration of human IgG on the trench was reduced to 50%, the antibody-nanotube attachment% dramatically improved, as shown in Figure 3c. This trend continued even at the more reduced concentration of 10% of human IgG on the trench, as shown in Figure 3d. The nanotube attachment % reached a maximum of 100 % when the concentration of human IgG on the trench was 7 % (Figure 3e). For concentrations of human IgG on the trenches of less than 7 % the nanotube attachment % decreased, as shown in Figure 3f. The change in antibody-nanotube attachment % as a function of the human-IgG concentration on the trenches is summarized by the thin solid line in Figure 4. Recently, SzleiferAs group computed the binding % of protein to ligand by molecular theory as a function of the concentration of the ligand. This model contained the interaction between acceptors and ligands at the end of polymer chains on the surface.[36] The computed result (the thick line in Figure 4) showed that the concentration of human IgG on the trenches at maximum nanotube attachment is also around 7 %. This excellent agreement indicates that antibody-coated nanotubes can be attached into trenches with human IgG on surfaces with high accuracy and high yield. This is achieved when the lateral repulsive antibody–antibody interactions and the degree of freedom for protein orientation are optimized by means of spacing the human IgG over the appropriate distance on the surface.

Figure 3.

AFM images of antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes attached to trenches filled with human IgG in concentrations of a) 0 %, b) 70 %, c) 50 %, d) 10 %, e) 7 %, and f) 3 %. BSA was used as a spacer to dilute the human-IgG concentration. Scale bar= 500 nm.

Figure 4.

Experimental attachment% of antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes on human-IgG-assembled trenches as a function of the human-IgG concentration. The thin solid line represents the result when BSA was used as a spacer, while the dotted line represents the results for PEG as a spacer. The thick line is the theoretical attachment% of receptor on the ligand surface as a function of the ligand concentration.[36]

We also investigated the antibody-nanotube attachment % by using PEG spacers. As shown in the dotted line in Figure 4, maximum attachment was also obtained at 7 %, the same concentration as observed for the BSA spacer. However, in the case of the PEG spacer, a steeper decline of the attachment% was observed as the human-IgG concentration was increased over the maximum point. This rapid decrease of attachment % could be due to the conformation change of the PEG spacers on the trenches. When the concentration of human IgG on the trench is increased, the PEG spacer tends to be stretched because of the repulsive force between the closely packed IgG molecules.[36] The stretched PEG spacer likely destabilizes the antibody–IgG binding because the distance between the antihuman-IgG molecules and the PEG molecules is too close, which increases the repulsive interaction between the two molecules. This additional repulsive interaction may reduce the antibody-nanotube attachment % rapidly for increasing IgG concentrations if PEG is used as a spacer.

In conclusion, the statistical percentage of antibody-coated nanomaterial attachment on complementary antigen-patterned surfaces was evaluated as a function of antigen concentration. Antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes were immobilized on trenches patterned as an array, filled with human IgG via antibody–antigen interactions. The antibody-nanotube attachment on the trenches was nearly 100 % when the concentration of IgG on the trench was diluted to 7 % with BSA or PEG spacers. The maximum yield of the antibody-nanotube attachment on the antigen-patterned surfaces was achieved by increasing the distance between human-IgG molecules using these spacer molecules. The comparison between the experimental outcome and the theoretical model reveals new physical insights into the dynamics of antibody–antigen recognition influenced by molecular-conformation changes. It reveals that the insertion of spacing molecules on substrates reduced the antibody–antibody lateral repulsive interaction and increased the antibody–protein attractive interaction simultaneously. While the maximum nanotube attachment % occurred at the same protein concentration on trenches with both BSA and PEG spacers, the type of spacers may add another factor for controlling the tube-attachment percentage. As the IgG concentration increases, the conformation of the spacers may be changed and this stretched conformation may influence the antibody–antigen interaction. Previously, this fabrication method has shown the potential for the immobilization of two types of antibody-coated nanotubes at different locations simultaneously on the corresponding antigen areas.[28] Therefore, this biomolecular recognition-based device assembly may become a versatile method to locate multiple nanomaterials at different targeted areas on surfaces when antigen and spacer concentrations are optimized. It should be noted that capillary forces may also have a significant effect for the alignment of antibody-coated nanotubes in parallel.[39] This effect is supported by our recent observation that the yield of antibody-nanotube attachment decreased significantly when antibody-coated nanotubes were aligned perpendicularly to the trenches.[40] It is obvious, however, that antibody-coated nanotubes do not attach on trenches without the antibody–antigen recognition. Therefore, the alignment of antibody-coated nanotubes may be affected by capillary forces in addition to biomolecular recognition.

Experimental Section

Antibody-coated nanotubes and antigen-patterned substrates were fabricated by the same methods published previously.[20, 28] In order to fabricate antibody-coated nanotubes, template nanotubes were coated with antihuman-IgG. The template nanotubes were self-assembled from bolaamphiphile peptide monomers in NaOH/citric acid solution via three-dimensional intermolecular hydrogen bonds, and the synthesis of these peptide nanotubes is described in previous publications.[31, 32] After the template nanotubes were centrifuged and run through size-separation columns, a 1 mL solution of the resulting nanotubes (10 mm) with average diameters of 100 nm were incubated with a 1 mL solution of antihuman-IgG in a pH 7.2 phosphate buffer (50 µg mL–1).[41] After 48 hrs, the anti-human-IgG was coated on the template nanotubes to form the antibody-coated nanotubes.[20] The antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes were washed with nanopure water and centrifuged twice to remove unbound antihuman-IgG before mixing with the human-IgG-patterned substrates. The array of IgG-coated trenches on the surface was patterned by the following procedure. First, 17-methoxyheptadecane-1-thiol (0.01 mm) was self-assembled on Au substrates in 99 % ethanol at room temperature for 24 hrs, and then a series of trenches (150 nm; 600 nm) were written by shaving the methoxythiol SAM with a Si3N4 tip (Veeco Metrology) of an AFM (Nanoscope IIIa and MultiMode microscope, Digital Instruments).[35] 17-methoxyheptadecane-1-thiol was used because this SAM showed a strong resistance to nonspecific protein binding.[42, 43] These trenches were patterned by using customized Nanoscript software (Veeco Metrology). After the substrate was washed with nanopure water, a series of human-IgG solutions mixed with BSA or thiol-polyethylene glycol (PEG)-5000 (thiol-PEG) in various IgG concentrations were incubated with the substrates for 10 h at 4°C. All mixtures of IgG, BSA, and thiol-PEG assembled on the shaved trenches of Au substrates via thiol–Au interactions. Thiol-PEG was purchased from Nektar and all other chemicals were from Sigma–Aldrich. For all of these substrate fabrications, the sum of the IgG and spacer concentrations was adjusted to 2 % in aqueous solution. After antihuman-IgG-coated nanotubes were incubated in the pH 8 buffer solution containing the IgG-patterned substrates for 12 h at 4°C, the resulting substrates were washed with nanopure water and the attachment of the antibody-coated nanotubes was imaged by AFM. This incubation time allows the nanotube absorption to reach equilibrium,[44] which was necessary to compare the experimental result to the theoretical outcome because the nanotube-attachment% was computed under equilibrium conditions. Overall, we examined 300 trenches for each IgG concentration to obtain statistical data for the attachment% of the antibody-coated nanotubes on those trenches. The attachment % was obtained by counting the number of trenches that had antibody-coated nanotubes attached to them, as seen in the AFM images.

Acknowledgments

[**] This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-FG-02–01ER45935) and the National Science Foundation CARRER Award (ECS-0103430) and partially supported by the NIH MBRS SCORE grant (2-S06-GM60654). The Hunter College infrastructure is supported by the National Institutes of Health via the RCMI program (G12-RR-03037). H.M. thanks Prof. Igal Szleifer for providing the computational results of the protein–ligand attachment percentage and also appreciates the very useful discussions.

References

- [1].Wang ZL, Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 432. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sun Y, Xia Y, Science 2002, 298, 2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gou LF, Murphy CJ, Nano Lett 2003, 3, 231. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pinna N, Weiss K, Urban J, Pileni MP, Adv. Mater 2001, 13, 261. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jin RC, Cao YW, Mirkin CA, Kelly KL, Schatz GC, Zheng JG, Science 2001, 294, 1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Puntes VF, Scher EC, Alivisatos AP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 12700. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yu L, Banerjee IA, Matsui H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 14837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Jen AKY, Schulten K, Nat. Mater 2003, 2, 577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Naik RR, Stringer SJ, Agarwal G, Jones SE, Stone MO, Nat. Mater 2002, 1, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gao X, Matsui H, Adv. Mater 2005, 17, 2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang Y, Duan X, Cui Y, Lauhon LJ, Kim KH, Lieber CM, Science 2001, 294, 1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith PA, Nordquist CD, Jackson TN, Mayer TS, Martin BR, Mbindyo J, Mallouk TE, Appl. Phys. Lett 2000, 77, 1399. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lumsdon SO, Kaler EW, Velev OD, Langmuir 2004, 20, 2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hamers RJ, Beck JD, Eriksson MA, Li B, Marcus MS, Shang L, Simmons J, Streifer JA, Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 280. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ryan KM, Mastroianni A, Stancil KA, Liu H, Alivisatos AP, Nano Lett 2006, 6, 1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Huang XMH, Caldwell R, Huang LM, Jun SC, Huang MY, Sfeir MY, O’Brien SP, Hone J, Nano Lett 2005, 5, 1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rao SG, Huang L, Setyawan W, Hong SH, Nature 2003, 425, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Niemeyer CM, Angew. Chem 2001, 113, 4254; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 4128. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Matsui H, Porrata P, Douberly GEJ, Nano Lett 2001, 1, 461. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nuraje N, Banerjee IA, MacCuspie RI, Yu L, Matsui H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 8088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reches M, Gazit E, Science 2003, 300, 625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hayashi T, Sano K, Shiba K, Kumashiro Y, Iwahori K, Yamashita I, Hara M, Nano Lett 2006, 6, 515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Braun E, Eichen Y, Sivan U, Ben-Yoseph G, Nature 1998, 391, 775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mbindyo JKN, Reiss BD, Martin ER, Keating CD, Natan MJ, Mallouk TE, Adv. Mater 2001, 13, 249. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sharma J, Chhabra R, Liu Y, Ke YG, Yan H, Angew. Chem 2006, 118, 744; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nyamjav D, Ivanisevic A, Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Park S-J, Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Science 2002, 295, 1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhao Z, Banerjee IA, Matsui H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bentzen EL, House F, Utley TJ, Crowe JE, Wright DW, Nano Lett 2005, 5, 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Alivisatos AP, Gu WW, Larabell C, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2005, 7, 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Matsui H, Gologan B, J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 3383. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kogiso M, Ohnishi S, Yase K, Masuda M, Shimizu T, Langmuir 1998, 14, 4978. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Douberly GJ, Pan S, Walters D, Matsui H, J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 7612. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Djalali R, Chen Y-F, Matsui H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu GY, Xu S, Qian YL, Acc. Chem. Res 2000, 33, 457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Longo G, Szleifer I, Langmuir 2005, 21, 11342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chen CC, Dormidontova EE, Langmuir 2005, 21, 5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nap R, Szleifer I, Langmuir 2005, 21, 12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Liu S, Tok JB-H, Locklin J, Bao Z, Small 2006, 2, 1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yang L, Matsui H, 2007, unpublished results [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gao X, Djalali R, Haboosheh A, Samson J, Nuraje N, Matsui H, Adv. Mater 2005, 17, 1753. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chapman RG, Ostuni E, Takayama S, Holmlin RE, Yan L, Whitesides GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 8303. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ostuni E, Chapman RG, Holmlin RE, Takayama S, Whitesides GM, Langmuir 2001, 17, 5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Im J, Huang L, Kang J, Lee M, Lee DJ, Rao SG, Lee N, Hong SH, J. Chem. Phys 2006, 124, 224707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]