Modulation of pore environment is an effective strategy to optimize guest binding in porous materials.

Modulation of pore environment is an effective strategy to optimize guest binding in porous materials.

Abstract

Modulation of pore environment is an effective strategy to optimize guest binding in porous materials. We report the post-synthetic modification of the charge distribution in a charged metal–organic framework, MFM-305-CH3, [Al(OH)(L)]Cl, [(H2L)Cl = 3,5-dicarboxy-1-methylpyridinium chloride] and its effect on guest binding. MFM-305-CH3 shows a distribution of cationic (methylpyridinium) and anionic (chloride) centers and can be modified to release free pyridyl N-centres by thermal demethylation of the 1-methylpyridinium moiety to give the neutral isostructural MFM-305. This leads simultaneously to enhanced adsorption capacities and selectivities (two parameters that often change in opposite directions) for CO2 and SO2 in MFM-305. The host–guest binding has been comprehensively investigated by in situ synchrotron X-ray and neutron powder diffraction, inelastic neutron scattering, synchrotron infrared and 2H NMR spectroscopy and theoretical modelling to reveal the binding domains of CO2 and SO2 in these materials. CO2 and SO2 binding in MFM-305-CH3 is shown to occur via hydrogen bonding to the methyl and aromatic-CH groups, with a long range interaction to chloride for CO2. In MFM-305 the hydroxyl, pyridyl and aromatic C–H groups bind CO2 and SO2 more effectively via hydrogen bonds and dipole interactions. Post-synthetic modification via dealkylation of the as-synthesised metal–organic framework is a powerful route to the synthesis of materials incorporating active polar groups that cannot be prepared directly.

Introduction

The release of CO2 and SO2 into the atmosphere from combustion of fossil fuels causes significant environmental problems and health risks.1,2 The wholesale replacement of the carbon-based energy supply is highly challenging, not least because of the existing infrastructure.3 It is therefore vital to mitigate the emissions of these acidic gases post combustion. At present, several technologies are used to capture CO2 and SO2, such as amine scrubbing, absorption in organic solvents, ionic liquids and limestone slurry.4–7 However, the considerable costs and the substantial energy input required for system regeneration significantly limit their long-term application. Powerful drivers therefore exist to develop new systems showing high adsorption capacity, selectivity, storage density and excellent reversibility to sequester these gases.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) constructed from metal ions and clusters bridged by organic ligands are an emerging class of porous materials showing highly crystalline structures and great promise for gas adsorption and storage.8 MOFs can exhibit very high surface areas and, more importantly, have tunable pore environments with predictable pore size9 and can incorporate specific functional groups.10–14 MOFs have been studied extensively as sorbents for CO2 under post-combustion conditions.11,13–22 In contrast, adsorption of SO2 in MOFs has been rarely reported due to the limited stability of coordination compounds to highly reactive and corrosive SO2.21–27 Development of new stable porous materials with optimal SO2 and CO2 adsorption property thus remains significant challenge. Optimising the interactions between hosts and substrate molecules to enhance the storage capacity, density and selectivity is the key to overcoming these barriers. For this reason, visualisation of the host–guest interactions involved in the MOF–gas binding interactions is crucial for the design of new materials. Interrogation of adsorption mechanisms by in situ experiments as a function of gas loading can afford key insights into the preferred binding sites within pores and the interaction to the pore interior.13,14,21,22 Open metal sites11,28 and pendent functional groups (e.g., amine, hydroxyl group and nitrogen-containing aromatic rings)13,14,21,22,29 have been found to act as specific sites for CO2 and SO2 binding.

Ionic liquids are composed of cations such as ammonium, pyridinium, phosphonium and imidazolium groups, and the solubility of CO2 and SO2 in these systems is often high owing to strong acid–base interaction.6,30–32 The incorporation of functionalized organic ligands within MOFs,23–25 and post synthetic modification can be used to control the number and types of functional groups within the pores.15–17 Cleavage of C–N bonds and hydrolysis of methyl viologen in alkaline solution have been observed.18,19 However, the dealkylation of pre-formed MOFs has not been reported previously, although adsorption of CO2 in two imidazolium–pyridinium cation-containing MOFs has been observed.10,33 We report the synthesis of a highly unusual charged material MFM-305-CH3, [Al(OH)(L)]Cl, [(H2L)Cl = 3,5-dicarboxy-1-methylpyridinium chloride] incorporating cationic (methylpyridinium) and anionic (chloride) components giving the material zwitterionic features. By heating MFM-305-CH3 at 180 °C, the 1-methylpyridiniumdicarboxylate ligand undergoes in situ demethylation to give the pyridine-based neutral complex MFM-305 showing the same overall framework topology. Demethylation coupled to loss of chloride anion exposes the bridging hydroxyl group in the MOF pore for hydrogen bonding to substrates, with MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 showing distinct charge distributions and pore environments decorated with different functional groups. This provides a unique platform to investigate the precise roles of Lewis acid, Lewis base, chloride, methyl, pyridine and hydroxyl groups in the binding of guest molecules. Through in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction, neutron diffraction, IR, 2H NMR and neutron spectroscopic experiments, the binding of CO2 and SO2 has been comprehensively investigated in these two porous materials. All experiments show that the binding domains for CO2 and SO2 molecules are directly affected by the tuning of surface charge distribution and functional groups. Significantly, simultaneously enhanced adsorption capacity and selectivity have been observed on going to MFM-305. We also report a unique study of structural dynamics of restricted guest molecules in MOFs as a function of temperature, showing the unprecedented mobility of CO2 molecule within the pores.

Results and discussion

Structural analysis of MFM-305-CH3

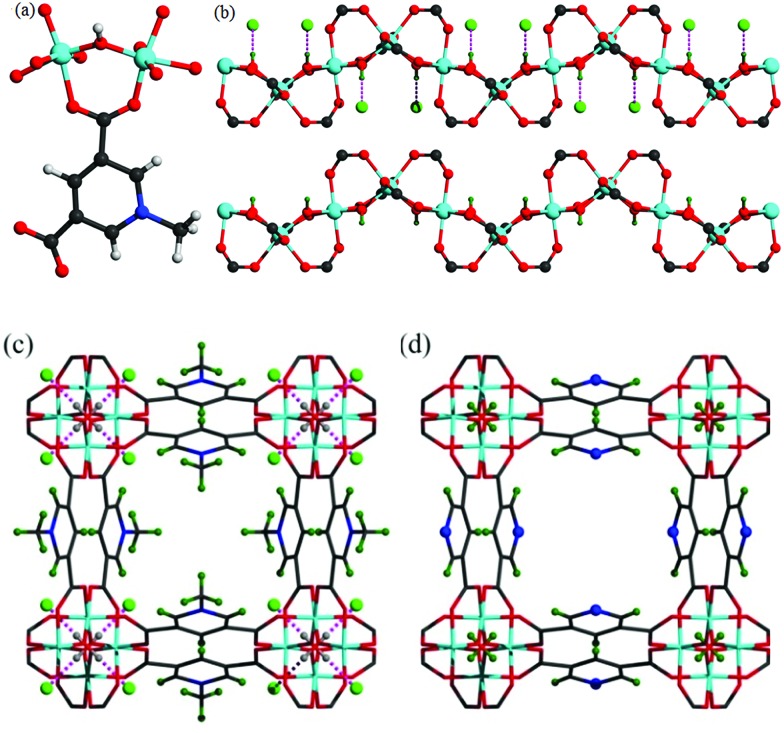

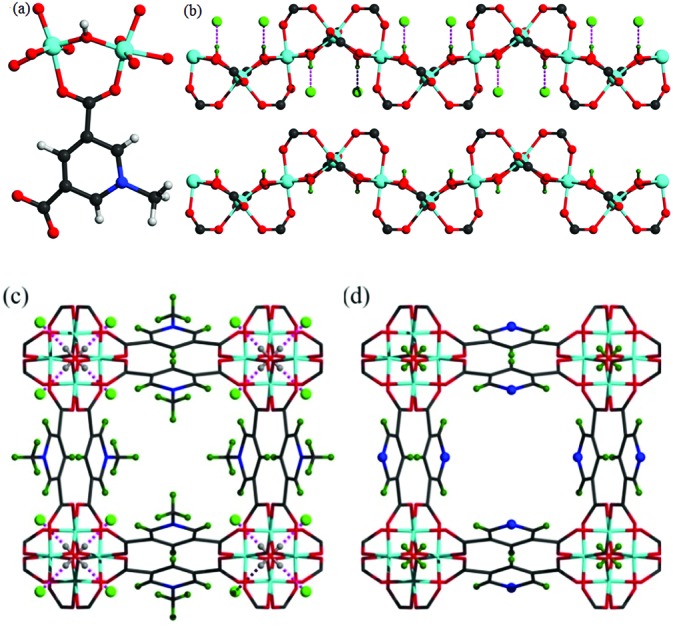

Solvothermal reaction of AlCl3·6H2O, [H2L]Cl ([H2L]Cl = 3,5-dicarboxy-1-methylpyridinium chloride) in a mixture of methanol and water (v/v = 12) at 130 °C for 3 days afforded MFM-305-CH3-solv, [Al(OH)(L)]Cl·solv, as a white crystalline powder in ca. 45% yield. The structure of MFM-305-CH3-solv has been determined by high resolution synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction (SPXRD). MFM-305-CH3-solv crystallizes in the space group I41/amd and has an open structure comprising cis-connected, corner-sharing chains of [AlO4(OH)2]∞ bridged by dicarboxylate ligands. The AlIII centre shows octahedral coordination defined by four carboxylate oxygen atoms from the ligand [Al–O = 2.048(8) and 1.881(3) Å; each appears twice] and two oxygen atoms from two μ2-hydroxyl groups [Al–O = 1.776(6) Å]. Adjacent AlIII centers are linked by a μ2-hydroxyl group to form an extended chain of [AlO4(OH)2]∞ along the c axis. The ligands further bridge [AlO4(OH)2]∞ chains to give a three dimensional network with square-shaped channels filled with disordered guest solvents. The window size of the channel is approximately 4.6 × 4.6 Å taking van der Waals radii into consideration (Fig. 1 and S23†). Overall, the metal–ligand connection in MFM-305-CH3-solv is comparable to that in MFM-300 (ref. 21) and CAU-10.34 The total free solvent volume in MFM-305-CH3-solv was estimated by PLATON/SOLV to be 28.5%.35

Fig. 1. (a) View of the coordination environment for ligand L– and the Al(iii) centre. (b) View of the corner-sharing octahedral chain of [AlO4(OH)2]···Cl. The μ2-(OH) groups form hydrogen bond to Cl–. Views of (c) MFM-305-CH3 and of (d) MFM-305. The pore size is ∼4.6 × 4.6 Å for MFM-305-CH3 and ∼5.6 × 5.6 Å for MFM-305 taking into consideration van der Waals radii. The methyl groups (olive) and chloride ions (green) in MFM-305-CH3; N atoms (blue) and hydroxyl group (olive) in MFM-305.

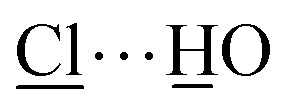

Guest solvent molecules in the pores can be removed by heating at 110 °C under vacuum for 10 h to give the desolvated material MFM-305-CH3, which retains the structure of the solvated material as determined by SPXRD. As expected, the framework of desolvated MFM-305-CH3 is cationic since it incorporates pyridinium moieties, and these are balanced by chloride ions that hydrogen bond to the hydroxyl groups and aromatic –CH groups on the pyridinium ring [ = 2.01(1) Å;

= 2.01(1) Å;  = 2.47(1) Å].36,37 As a result, the μ2-OH groups in MFM-305-CH3 are hindered by the Cl– ions and are thus not accessible to guest molecules, leaving 1-methylpyridinium and chloride ion as potential sites for guest interaction. The stability and rigidity of the framework in MFM-305-CH3 has been confirmed by variable temperature PXRD (50–550 °C) (Fig. S2†), which confirms framework decomposition above 450 °C.

= 2.47(1) Å].36,37 As a result, the μ2-OH groups in MFM-305-CH3 are hindered by the Cl– ions and are thus not accessible to guest molecules, leaving 1-methylpyridinium and chloride ion as potential sites for guest interaction. The stability and rigidity of the framework in MFM-305-CH3 has been confirmed by variable temperature PXRD (50–550 °C) (Fig. S2†), which confirms framework decomposition above 450 °C.

Structural analysis of MFM-305

TGA-MS measurements of desolvated MFM-305-CH3 shows that the methyl and chloride groups can be removed from the pore at 150–300 °C (Fig. S3†) giving the iso-structural neutral material MFM-305. To prepare a bulk sample of MFM-305, as-synthesized MFM-305-CH3-solv was heated at 180 °C under vacuum for 16 h to completely remove the guest solvents and CH3+/Cl– (Fig. S4†). A change in color from white to pale yellow is observed on going from MFM-305-CH3 to MFM-305. SPXRD analysis of MFM-305 confirms that it retains the same space group I41/amd, but shows a slight contraction along the a/b axis (Δ = 0.06%) and c axis (Δ = 4%) with an extended channel size of 5.6 × 5.6 Å. The total free solvent volume in MFM-305 was estimated by PLATON/SOLV to be 39.9%.35 The most significant change is conversion of the methylpyridinium species in MFM-305-CH3 to a free pyridyl moiety in MFM-305 and formal loss of CH3Cl. The bridging hydroxyl groups in MFM-305 are now exposed because of the removal of chloride (see below). Moreover, the pyridyl groups are now accessible within the pores of MFM-305, and IR spectroscopy confirms the loss of the stretching vibration of the –CH3 group at 2988 cm–1 on going from MFM-305-CH3 to MFM-305 (Fig. S7†). The complete removal of Cl– in MFM-305 has been confirmed by XPS spectroscopy (Fig. S5 and S6†). Interestingly, the post-synthetic modification leads to distinct pore environments for isostructural MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305, and thus provides an excellent platform to examine their capabilities of guest binding and selectivity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of studying the mechanism of guest adsorption within an isostructural pair of MOFs with charged and neutral pore environments of this kind (Table 1).

Table 1. Unit cell parameters of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305.

| MFM-305-CH3 | MFM-305 | |

| Formula | Al(OH)(C8H6NO4)Cl | Al(OH)(C7H3NO4) |

| M r | 259.6 | 209.1 |

| Space group | I41/amd | I41/amd |

| a, b (Å) | 21.48(6) | 21.495(3) |

| c (Å) | 10.90(3) | 10.457(2) |

| Volume (Å3) | 5030(30) | 4831.6(1) |

| BET surface area/m2 g–1 | 256 | 779 |

| Pore volume (P/P0 = 0.95)/cm3 g–1 | 0.181 | 0.372 |

| Pore size (HK)/Å | 5.2 | 6.2 |

| Pore volume (Cal.)/cm3 g–1 | 0.209 | 0.347 |

| Pore size (Cal.)/Å | 4.6 | 5.6 |

| CO2 uptake/mmol g–1 (273/298 K) | 2.98/2.39 | 3.55/2.65 |

| SO2 uptake/mmol g–1 (273/298 K) | 5.29/5.16 | 9.05/6.99 |

Gas adsorption analysis

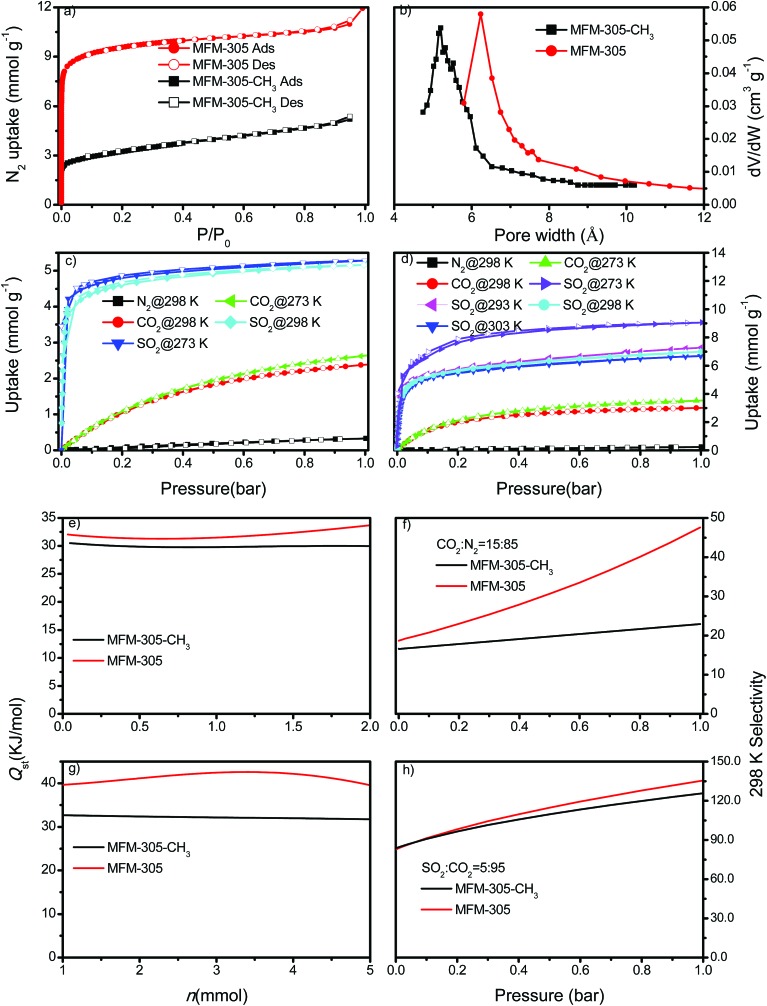

N2 isotherms at 77 K for desolvated MFM-305-CH3 and desolvated MFM-305 both show type-I profiles confirming retention of microporosity. The BET surface area and total pore volume for MFM-305-CH3 are estimated to be 256 m2 g–1 and 0.181 cm3 g–1, respectively, and 779 m2 g–1 and 0.372 cm3 g–1, respectively, for MFM-305 confirming a ∼2.0 fold increase in porosity upon the modification (Fig. 2a, Table S1†). Horváth–Kawazoe (HK) analysis38 of the N2 isotherm confirms a pore size distribution centered at 5.2 and 6.2 Å for MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305, respectively (Fig. 2b). The increase in pore size is consistent with those confirmed by X-ray structural analysis.

Fig. 2. Gas adsorption data. (a) Adsorption isotherms for N2 in MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 at 77 K and 1.0 bar. (b) Comparison of the pore size of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305. (c) Adsorption isotherms for CO2, SO2 and N2 in MFM-305-CH3 at 273 and 298 K and 1.0 bar. (d) Adsorption isotherms for CO2, SO2 and N2 in MFM-305 at 273, 293, 298 and 303 K and 1.0 bar. Variation of isosteric heat of adsorption Qst as a function of (e) CO2 and (g) SO2 uptake for MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 calculated from adsorption isotherms measured at 273 and 298 K. Comparison of the IAST selectivity of (f) CO2/N2 (15 : 85) and (h) SO2/CO2 (5 : 95) in MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 at 298 K.

CO2 isotherms at 195 K and 1.0 bar show saturated uptake capacities of 4.23 and 5.69 mmol g–1 for MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305, respectively (Fig. S24†). The increase (ca. 33%) is much smaller than that of N2 isotherm, consistent with the reduced kinetic diameter of CO2 (3.30 Å) comparing to N2 (3.89 Å). At 273 K and 298 K, MFM-305-CH3 shows CO2 uptakes of 2.67 and 2.41 mmol g–1, respectively, at 1.0 bar (Fig. 2c and d). In comparison, the values for MFM-305 were recorded as 3.55 and 3.02 mmol g–1, respectively. The CO2 uptake at 0.15 bar, which is relevant to its partial pressure in flue gas, are 0.86 mmol g–1 for MFM-305-CH3 and 1.76 mmol g–1 for MFM-305. This uptake is higher than that of H3[(Cu4Cl)3(BTTri)8]-en (BTTri = 1,3,5-tris(1H-1,2,3-triazol-5-yl)benzene) (0.682 mmol g–1)39 and NH2–MIL-101(Cr) (0.5 mmol g–1),47 but lower than that of MFM-300(Al) (2.64 mmol g–1),21 MOF-74(M) (M = Mg, Ni, Co) (5.3, 2.7, 2.7 mmol g–1, respectively)48 and the amine-modified MIL-101 (4.2 mmol g–1)49 under the same conditions.

The excellent stability of these two MOFs motivated us to measure the adsorption isotherm of SO2. At 298 K and 1.0 bar, MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 show SO2 adsorption capacities of 5.16 and 6.99 mmol g–1, respectively (Fig. 2c and d). Importantly, the SO2 uptake is fully reversible in both materials, and no loss of crystallinity or porosity was observed for the regenerated samples. At 298 K and 1.0 bar, the SO2 uptake of MFM-305 is notably higher than that of most solid sorbents in the literature (Fig. S29,† Table S2†), and only lower than that of MFM-300(In) (8.28 mmol g–1), Mg-MOF-74 (8.6 mmol g–1), Ni(bdc)(ted)0.5 (9.97 mmol g–1) (H2bdc = terephthalic acid; ted = triethylenediamine), MFM-202a (10.2 mmol g–1) and SIFSIX-1-Cu (11.01 mmol g–1), which have higher surface areas of 1071, 1525, 1783, 2220 and 3140 m2 g–1, respectively.21–27 At 303 K, MFM-305 shows an adsorption capacity for SO2 of 6.70 mmol g–1 at 1.0 bar, and a high uptake of 3.94 mmol g–1 at 0.025 bar, comparable to the best-behaving MOFs.50 Using the total pore volume, the storage density of SO2 in a given MOF system can be estimated; those for MFM-305-CH3, SIFSIX-1-Cu-i, MFM-305 and MFM-300(In) are calculated to be 1.83, 1.70, 1.20 and 1.27 g cm–3, respectively at 298 K and 1.0 bar. Thus, MFM-305-CH3 gives a notably higher storage density that is 70% of liquid density of SO2 at 263 K (2.63 g cm–3), indicating the presence of efficient packing of adsorbed gas molecules within the pore.

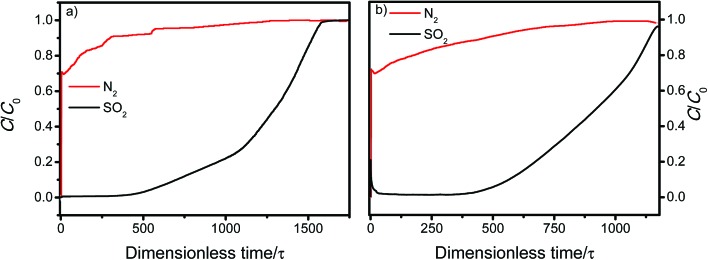

Both MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 show highly selective SO2 uptakes. At 298 K, MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 exhibit very steep adsorption profiles for SO2 between 0 and 20 mbar, leading to an uptake of 3.59 and 3.94 mmol g–1, respectively, accounting for 70% and 56% of the total uptake at 1.0 bar. In contrast, under the same conditions, MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 show a much lower uptake of CO2 (i.e., 0.15 and 0.40 mmol g–1, respectively). Moreover, the uptakes of N2 under the same conditions are negligible (<0.01 mmol g–1) in these two materials. The isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) for CO2 in MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 both lie in the range of 29–34 kJ mol–1; on average the Qst of MFM-305 is ca. 3 kJ mol–1 higher than MFM-305-CH3 (Fig. 2e). The Qst for adsorption of SO2 in MFM-305 and MFM-305-CH3 is estimated to be 39–43 kJ mol–1 and 30–32 kJ mol–1, respectively (Fig. 2g). MFM-305 displays a higher Qst value for SO2 uptake than MFM-305-CH3, indicating the presence of enhanced host–guest binding affinity upon the pore modification. To further evaluate their potential for gas separation, the selectivities for CO2/N2(SCN), SO2/CO2 (SSC) and SO2/N2 (SSN) at 298 K have been calculated using ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST)40 over a wide range of molar compositions (i.e., 1 : 99 to 50 : 50) (Fig. 2f, h, S31 and S32†). Significantly, for a 5 : 95 mixture of SO2/CO2 and a 15 : 85 mixture of CO2/N2, MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 both show exceptionally high IAST selectivities, and these are enhanced by the pore modification. The calculations for SSN are subject to large uncertainties due to the extremely low uptake of N2. The adsorptive removal of low concentration SO2 by MFM-305 has been confirmed by breakthrough experiments in which a stream of SO2 (2500 ppm diluted in He/N2) was passed through a packed bed of MFM-305 under ambient conditions (Fig. 3a). As expected, He and N2 were the first to elute through the bed, whereas SO2 was retained selectively under dry condition (Fig. 3a). On saturation (dimensionless time > 500), SO2 breaks through from the bed and reaches saturation gradually. The ability of MFM-305 to capture SO2 in the presence of moisture has also been demonstrated by breakthrough experiments using a wet stream of SO2 (Fig. 3b). In the presence of water vapor, the breakthrough of SO2 from MFM-305 slightly reduces to 420 (dimensionless time) as a result of competitive adsorption of water. Thus, the marked differences in adsorption profiles, uptake capacities, Qst between SO2, CO2 and N2, the corresponding IAST selectivity and the dynamic adsorption experiments indicate the potential of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 have the potential to act as selective adsorbents for CO2 and SO2.

Fig. 3. Dimensionless breakthrough curve of 0.25% SO2 (2500 ppm) diluted in He/N2 under (a) dry and (b) wet conditions through a fixed-bed packed with MFM-305 at 298 K and 1 bar.

Determination of binding domains for adsorbed CO2 and SO2

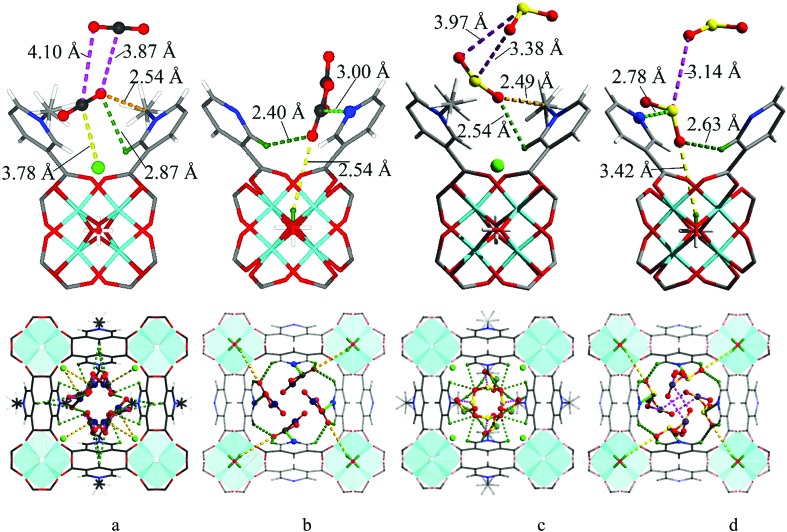

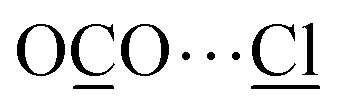

We sought to determine the binding domains for CO2 and SO2 in the pores of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 since comparison between the binding sites within these two materials affords a direct observation of the effect of pore environment on guest binding. High resolution SPXRD data were collected at 198 K for CO2-loaded samples and at 298 K for SO2-loaded samples at 1 bar. SPXRD data enabled full structural analysis via Rietveld refinement (Fig. S8–S22†) to yield the positions, orientations and occupancies of adsorbed CO2 and SO2 molecules (Fig. 4 and S33†). Overall, all gas-loaded samples retain the I41/amd space group and two crystallographically independent binding sites (I and II) are observed in each case.

Fig. 4. The crystal structures of CO2 and SO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 studied by powder diffraction at 298 K. (a) Interactions of CO2 molecule with the methyl, chloride ions and the –CH on pyridyl groups in MFM-305-CH3. (b) Interactions of CO2 molecule with the N- and C–H groups of pyridyl centre and the hydroxyl group in MFM-305. (c) Interactions of SO2 molecule with the methyl, chloride ions and the –CH on pyridyl groups in MFM-305-CH3. (d) Interactions of SO2 molecule with the N– and –CH centres of pyridyl and the hydroxyl group in MFM-305. Carbon, black; hydrogen, olive; oxygen, red; interactions between CO2 and frameworks C–H are shown in olive dashed line; interactions between adsorbed CO2 molecules and hydroxyl are shown in orange dashed line; interactions between adsorbed CO2 molecules and chloride ions are shown in yellow dashed line; interactions between adsorbed CO2 molecules and N atoms are shown in light green dashed line.

In CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3, COI2 (occupancy = 0.32) interacts with the methyl group with a H3C[combining low line]···O[combining low line]CO distance of 2.54(1) Å, indicating the formation of a weak hydrogen bond. COI2 also forms supramolecular interactions with aromatic –CH groups on neighboring pyridinium rings [OCO[combining low line]···H[combining low line]C = 2.87(2) Å]. Additionally, dipole interactions were observed between COI2 and Cl– [ = 3.78(1) Å, ∠O–C···Cl = 99.2(8)°].30,41 COII2 (occupancy = 0.41) binds to the aromatic –CH group [OCO[combining low line]II···H[combining low line]C = 3.50(1) Å]. Further dipole interactions were observed between COI2 and COII2 [OI···CII = 3.87(1) Å; OII···CI = 4.10(1) Å] in a typical T-shape arrangement.42

= 3.78(1) Å, ∠O–C···Cl = 99.2(8)°].30,41 COII2 (occupancy = 0.41) binds to the aromatic –CH group [OCO[combining low line]II···H[combining low line]C = 3.50(1) Å]. Further dipole interactions were observed between COI2 and COII2 [OI···CII = 3.87(1) Å; OII···CI = 4.10(1) Å] in a typical T-shape arrangement.42

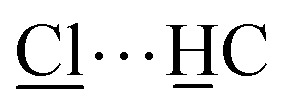

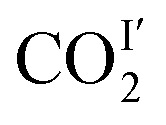

In CO2-loaded MFM-305,  (occupancy = 0.48) interacts with the hydroxyl group in an end-on mode [OH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]CO = 3.45(3) Å]. This distance is longer than that obtained for CO2-loaded MFM-300(Al) [2.298(4) Å] studied by PXRD at 273 K.20

(occupancy = 0.48) interacts with the hydroxyl group in an end-on mode [OH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]CO = 3.45(3) Å]. This distance is longer than that obtained for CO2-loaded MFM-300(Al) [2.298(4) Å] studied by PXRD at 273 K.20 also interacts with the exposed pyridine nitrogen atom via a dipole interaction [OC[combining low line]O···N = 2.89(1) Å]. Additionally, a series of weak supramolecular contacts of

also interacts with the exposed pyridine nitrogen atom via a dipole interaction [OC[combining low line]O···N = 2.89(1) Å]. Additionally, a series of weak supramolecular contacts of  to surrounding –CH groups [OCO[combining low line]···H[combining low line]C = 2.44(1); 2.73(1) Å] are also observed. Further dipole interactions are found between COI2 and COII2 with intermolecular CI′···OII′/CII′···OI′ distances of 3.09(1)/3.14(1) Å, comparable to that observed in dry ice [3.178(1) Å].42

to surrounding –CH groups [OCO[combining low line]···H[combining low line]C = 2.44(1); 2.73(1) Å] are also observed. Further dipole interactions are found between COI2 and COII2 with intermolecular CI′···OII′/CII′···OI′ distances of 3.09(1)/3.14(1) Å, comparable to that observed in dry ice [3.178(1) Å].42

At 298 K SO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 shows the SOI2 molecule (occupancy = 0.30) binding to two adjacent methyl groups simultaneously [OSO[combining low line]···H3C[combining low line] = 2.49(3) Å]. SOI2 also forms hydrogen bonds with surrounding –CH groups [OSO[combining low line]···H[combining low line]C = 2.54(2) Å]. SOII2 (occupancy = 0.47) lies perpendicular to SOI2 [SI···OII/SII···OI = 3.38(2) and 3.97(3) Å] and parallel to the pyridinium ring [OS[combining low line]O···HC[combining low line] = 3.95(1) Å]. The SO2 intermolecular distances within MFM-305-CH3 are comparable to that observed in the crystal structure of SO2 (3.10 Å),43 confirming the very efficient packing of adsorbed SO2 molecules leading to its high observed storage density.

In MFM-305,  (occupancy = 0.39) primarily binds to the pyridyl N-atom via a dipole interaction [OS[combining low line]O···N = 2.78(1) Å] and also forms hydrogen bonds with the exposed hydroxyl group [–OH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]SO = 3.42(4) Å] as well as the surrounding –CH groups [–CH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]SO = 2.63(3) and 3.14(3) Å]. Further dipole interactions were observed between SO2 molecules on sites I′ and II′ with intramolecular distance of 4.29(2) Å. Overall, these observations confirm that the methyl group and –CH groups are the primary binding sites in MFM-305-CH3 for both CO2 and SO2. In contrast, modulation of the pore environment in MFM-305 induces notable shifts of binding sites to the free pyridyl nitrogen center and hydroxyl group. This study offers a comprehensive understanding of the synergistic effect of functional groups on the binding of CO2 and SO2 in these materials.

(occupancy = 0.39) primarily binds to the pyridyl N-atom via a dipole interaction [OS[combining low line]O···N = 2.78(1) Å] and also forms hydrogen bonds with the exposed hydroxyl group [–OH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]SO = 3.42(4) Å] as well as the surrounding –CH groups [–CH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]SO = 2.63(3) and 3.14(3) Å]. Further dipole interactions were observed between SO2 molecules on sites I′ and II′ with intramolecular distance of 4.29(2) Å. Overall, these observations confirm that the methyl group and –CH groups are the primary binding sites in MFM-305-CH3 for both CO2 and SO2. In contrast, modulation of the pore environment in MFM-305 induces notable shifts of binding sites to the free pyridyl nitrogen center and hydroxyl group. This study offers a comprehensive understanding of the synergistic effect of functional groups on the binding of CO2 and SO2 in these materials.

Analysis of host–guest binding via inelastic neutron scattering (INS)

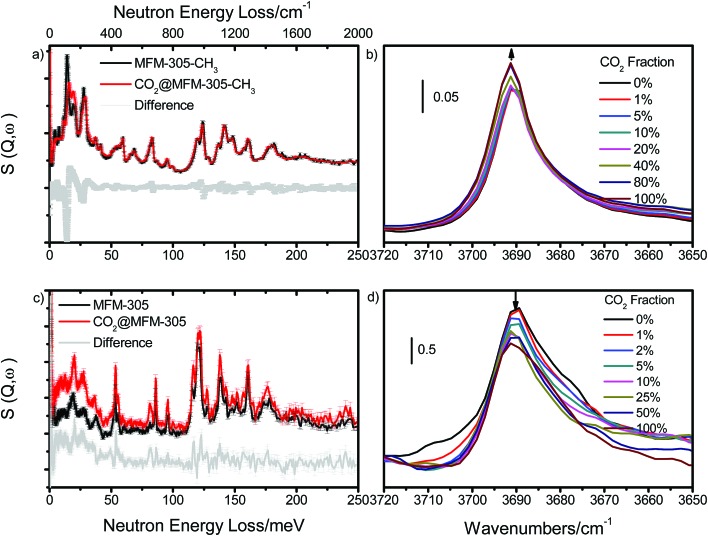

To directly visualise the multiple supramolecular host–guest binding modes in these systems, INS spectra of bare and CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 (1 gas/Al) were collected at 5 K (Fig. 5). In addition, the structural models obtained from X-ray crystallographic studies were optimized by DFT calculations. The corresponding DFT-calculated INS spectra show good agreement with the experimental data (Fig. S35–S39†). Comparison of the INS spectra of desolvated MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 shows (Fig. S35†) three distinct low-energy peaks at 13, 27, 36 and 19, 28, 37 meV, respectively, related to the lattice modes of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305. The most significant change is the absence of the –CH3 rotation/torsion mode at 20 meV in MFM-305, confirming full demethylation by the post-synthetic modification procedure. The groups of peaks observed at 40–85 meV and 85–200 meV in MFM-305-CH3 are assigned to wagging/bending modes of the bridging hydroxyl group and of the aromatic C–H bonds, respectively. As crystallographic studies confirm above, the hydroxyl groups within MFM-305-CH3 form hydrogen bonds to the chloride ion in the pores. Upon demethylation, the peaks at 40, 69 and 83 meV in MFM-305-CH3 shifts to higher energies at 53, 83, 115 and 119 meV in MFM-305, consistent with the removal of the chloride ions.

Fig. 5. Comparison of (a and c) the INS spectra and (b and d) IR spectra for bare MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305. INS and IR spectra offer vibrational information on the –CH3/–CH/–OH stretching and deformation region. (a) Comparison of the INS spectra for bare and CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3. (b) IR spectra in the ν(μ2-OH) stretch region of CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3. (c) Comparison of the INS spectra for bare and CO2-loaded MFM-305. (d) IR spectra of the ν(μ2-OH) stretch region of MFM-305 for CO2-loading. IR and INS data were collected at 298 K and 5 K, respectively.

Addition of CO2 in MFM-305-CH3 is accompanied by significant change to peaks at 13 and 27 meV, indicating stiffening of the lattice modes as a result of CO2 inclusion. Large intensity changes were observed for the peaks at 20 meV, indicating the hindrance of rotation motion of –CH3 groups upon CO2 binding, consistent with the formation of hydrogen bonds as observed in the structural models. This is further accompanied by small red shifts for the peaks between 85 and 200 meV (bending modes of –CH groups). Thus, the INS result confirms that the methyl and –CH groups are the effective binding sites for CO2 in MFM-305-CH3. Addition of CO2 in MFM-305 leads to similar changes of peaks at 19, 28 and 37 meV. Significant changes to peak at 53, 83, 115 and 119 meV indicate that the bridging hydroxyl is directly involved in binding to CO2. The peaks between 120 and 200 meV also show notable changes in the C–H modes on CO2 binding. This result confirms unambiguously that the –OH group and pyridine ring are the primary binding site for CO2 in MFM-305, in excellent agreement with the crystallographic results. Thus, the INS results have confirmed the shifts of primary binding sites upon the modification of pore charge distribution.

Analysis of CO2 binding via in situ synchrotron infrared micro-spectroscopy

In order to study the interaction between adsorbed CO2 molecules and the MOF hosts at 298 K, an in situ synchrotron IR micro-spectroscopic study22 was carried out as a function of CO2 loading. Upon desolvation of MFM-305-CH3 under a dry He flow, an absorption band at 3690 cm–1 corresponding to the ν(μ2-OH) stretching mode is observed. Upon dosing CO2 up to 1.0 bar, this peak remained at the same position, but the peak intensity increased slightly indicating a through-space effect due to the weak interaction between Cl– and CO2 molecules (Fig. 5b). In contrast, upon dosing desolvated MFM-305 with 1.0 bar CO2, the peak at 3690 cm–1 shifts very slightly but the peak intensity decreases notably (Fig. 5d) indicating the presence of an strong interaction between CO2 and hydroxyl groups, entirely consistent with the crystallographic study. The combination bands of the –C C– vibrations44 within MFM-305-CH3 centered at 1555 cm–1 shift to 1560 cm–1, and that at 1552 cm–1 in MFM-305 shifts to 1566 cm–1 upon CO2 loading, consistent with the formation of supplementary interactions between CO2 molecules and pyridinium or pyridyl rings (Fig. S40†). Thus, the observed changes in IR experiments gives further evidence and supports the distinct interactions between guest CO2 molecules and these two porous MOFs.

Analysis of host–CO2 binding via in situ2H NMR spectroscopy

The –CH3 group in the 1-methylpyridinium dicarboxylate linker represents a fast stochastic rotor or natural isolated gyroscope. As such, its rotational parameters can be used to track the possible binding interaction with the guest molecules.45 We were interested to probe further the dynamic changes of the methyl groups on CO2 binding by synthesising MFM-305-CD3 and studying it by solid state 2H NMR spectroscopy over a wide temperature range (90–300 K). MFM-305-CD3 was obtained using the same synthetic route described above but using the deuterated ligand, 3,5-dicarboxy-1-methyl-d3-pyridinium chloride. Two samples were used in this 2H NMR study: guest-free MFM-305-CD3 and CO2-loaded MFM-305-CD3.

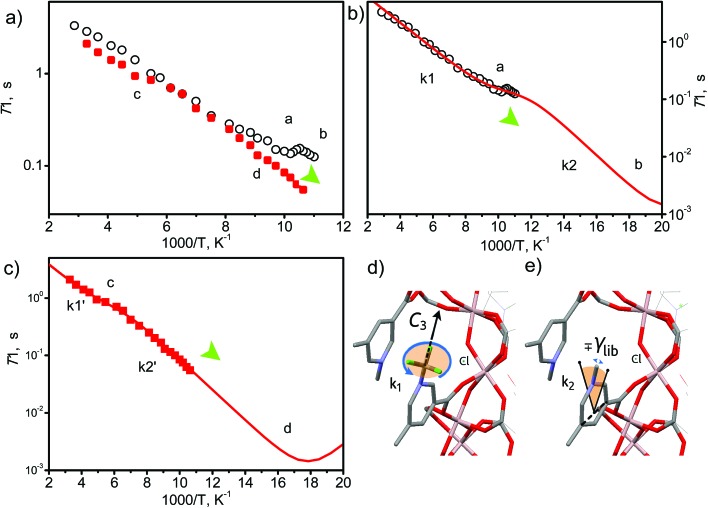

Typically the –CD3 group is expected to exhibit very fast uniaxial rotation and hence its dynamics can be probed by 2H NMR spin-lattice (T1) relaxation, which is sensitive to rapid (rate > 106 s–1) motions.45,46 The T1 relaxation curves (Fig. 6) show for both materials that the temperature dependence is characterised by two regions of monotonous decrease separated by a local minimum (marked as a and c in Fig. 6). Such behavior shows that in addition to the usual uniaxial rotations, the methyl groups perform another type of motion – a faster one, as it governs the relaxation curve notably at lower temperatures (marked b and d in Fig. 6). In CO2-loaded MFM-305-CD3, both modes are notably slower which is reflected in the behavior of the T1 curves behavior at ∼180 K and ∼100 K. A quantitative analysis requires a model of rotation (Fig. 6d and e): considering the close contact of the –CD3 group with the neighboring linker (d ∼ 3 Å), it is reasonable to assume that the slower (a, c) motion (k1, k1′) reflects the uniaxial rotation of the –CD3 group about its C3 symmetry axis aligned along the N–CD3 bond, while the faster (b, d) motion (k2, k2′) represents small angular librations of the rotating axis restricted within borders ±γlib.

Fig. 6. View of the temperature dependence of 2H NMR spin-lattice relaxation for –CD3 groups. (a) Experimental results for guest free MFM-305-CH3 (black circles) and for CO2@MFM-305-CH3 (1 mol per cavity) (red squares). (b and c) The simulated curve for MFM-305-CH3 and CO2@MFM-305-CH3 based upon two relaxation mechanisms corresponding to the two dynamic states of the –CD3 groups. (d and e) Representation of possible –CD3 motions in MFM-305-CH3 cavity.

Parameters derived within such a model confirm that the rotation along N–CD3 axis (E1 = 4.2 kJ mol–1, k10 = 2.1 × 1010 s–1) reaches a rate of k1 ∼ 108 s–1 at 100 K (a), while in the presence of the CO2 it is ∼10 times slower with k1′ ∼ 107 s–1 (E1′ = 4.2 kJ mol–1, k10′ = 1.8 × 109 s–1), and reaches 108 s–1 at 180 K (c). Hence, by interacting with CO2, the pre-exponential factor of the –CD3 rotation is affected. This indicates that although the interaction with CO2 is not sufficient to increase the activation barrier of the rotation, the dynamic density of guests around the methyl groups is tight enough and sufficient to slow down the rotation rate by 10-fold by random collisions. Similarly, the libration mode is affected as well and the pre-exponential is faster and reaches its characteristic minimum45 below 90 K (b, d). For MFM-305-CD3 its rate at 100 K is k2 ∼ 1011 s–1, while for CO2-loaded MFM-305-CD3 it is notably slower and can be resolved unambiguously (E2′ = 5.1 kJ mol–1, k20′ = 0.65 × 1013 s–1) with k2′ ∼ 1010 s–1 (100 K). Notably, the amplitude of the restricted librations also sense the presence of CO2 with γlib ∼ 5° decreasing to γlib′ ∼ 2°. This decrease in libration angle coupled with the strong deceleration of both motional modes by ∼10 times in the presence of CO2 evidences the interaction of CO2 guests with the methyl groups within the MOF pores.

Structural dynamics of restricted CO2 molecules in the pore

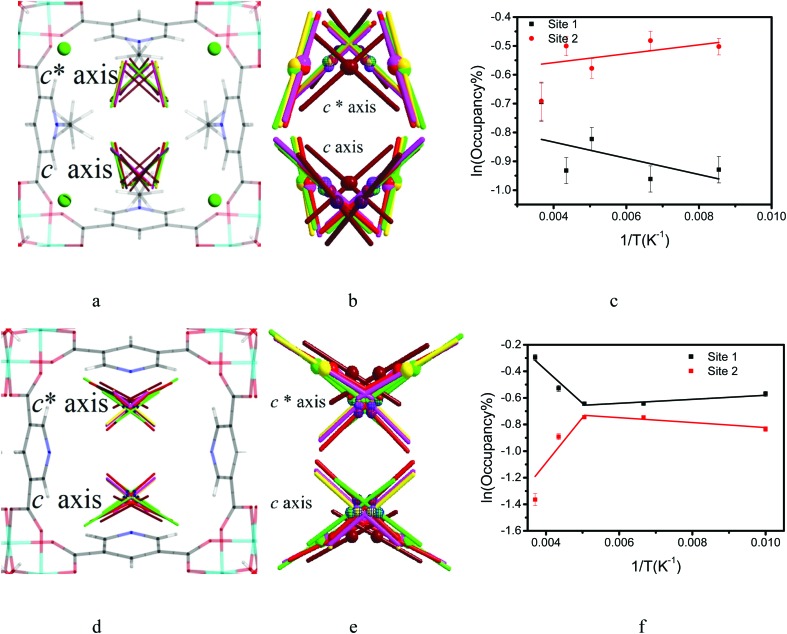

To investigate the dynamics of host–guest interaction, we sought to study the structural flexibility of restricted CO2 molecules (e.g., positions, orientations and occupancies) within the pores of MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 via variable temperature SPXRD. Le Bail analysis reveals changes in lattice parameters of CO2-loaded samples as a function of temperature (Fig. 7, Table S3†). As the temperature decreases from 273 K to 117 K, the lattice parameters of CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 contract along all directions (ΔV/V = 0.7%), whereas MFM-305 expands along c axis (Δc/c = 1.3%) and contracts along the a/b axes (Δa/a = 0.02%) as the temperature decreases from 270 K to 100 K (Fig. S41†). Throughout the temperature range studied, two independent binding sites for CO2 molecules were observed in both samples. In general, the intermolecular distances of MOF–CO2 and CO2–CO2 decrease continuously as the temperature decreases (Tables S3 and S4†).

Fig. 7. Comparison of the crystal structures of CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 and MFM-305 studied by synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction at variable temperatures. Dynamic structures of CO2 under different temperature (270 K, dark red; 230 K, red; 198 K, pink; 150 K, yellow; 117/100 K, bright green) in (a) MFM-305-CH3 and (d) MFM-305. (b and e) Enlarged views of the multiple CO2 regions in (a) and (d) at site I (solid symbol) and site II (patterned symbol). Occupancies of CO2 at site I and II in (c) MFM-305-CH3 and (f) MFM-305.

The CO2 supply was maintained at 1.0 bar on going from room temperature to 198 K. In MFM-305-CH3 the occupancy of CO2 (I + II) increased from 0.60 to 0.70 from 273 K to 230 K, with COI2 hydrogen bonding with the methyl group and the –CH groups on the pyridyl ring. The hydrogen bond distances [OCO[combining low line]I–H3C[combining low line]] decrease steadily from 3.10(2) to 2.38(2) Å from 273 K to 117 K, indicating that the strength of these hydrogen bonds is highly sensitive to temperature (Fig. 7, Table S4†). Interestingly, as the temperature decreases, we observe significant re-arrangement of restricted CO2 molecules at site I and II. COI2 molecules move closer to the pore surface and rotate to drive the oxygen atoms closer to the ligands to form stronger hydrogen bonds. COI2 and COII2 retain their T-shape arrangement, but move closer to each other. From 273 K to 117 K, the ratio [i.e. COI2/(COI2 + COII2) × 100%] of the occupancy of site I decreases from 50(2)% to 40(2)%, while the occupancy of site II increases from 50(2)% to 60(1)%. The activation energy (Ea) of the site configuration and occupancy was calculated using the Arrhenius equation as a function of temperature. From 273 K to 117 K, Ea for site I is 0.233 kJ mol–1, and for site II it is –0.128 kJ mol–1. The changes of site configuration and occupancy reveal that the host–guest binding is highly sensitive to temperature via intra-pore re-arrangement.

Variable temperature PXRD data were collected for MFM-305 using the same method.  forms hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl group and the –CH groups of the pyridyl ring, and the free N-center of the pyridyl ring interacts with CO2via dipole interactions. The hydrogen bond distance (OCO[combining low line]I′–H[combining low line]O) and the distance of CO2 to the N-center (N–OC[combining low line]OI′) both reduce from 4.20(3) to 3.34(4) and from 3.16(1) to 2.96(1) Å, respectively, as the temperature is lowered from 270 K to 100 K. The intermolecular distances between

forms hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl group and the –CH groups of the pyridyl ring, and the free N-center of the pyridyl ring interacts with CO2via dipole interactions. The hydrogen bond distance (OCO[combining low line]I′–H[combining low line]O) and the distance of CO2 to the N-center (N–OC[combining low line]OI′) both reduce from 4.20(3) to 3.34(4) and from 3.16(1) to 2.96(1) Å, respectively, as the temperature is lowered from 270 K to 100 K. The intermolecular distances between  and

and  (OCO[combining low line]I′–OC[combining low line]OII′ and OC[combining low line]OI′–O[combining low line]COII′) reduce from 5.03(2) to 3.07(1) Å and 5.04(3) to 2.94(1) Å, respectively, from 270 to 100 K (Fig. 7, Table S4†). From 270 K to 198 K, the total CO2 occupancy increases from 0.5 to 0.92, which was retained to 100 K. From 270 K to 198 K, the ratio of

(OCO[combining low line]I′–OC[combining low line]OII′ and OC[combining low line]OI′–O[combining low line]COII′) reduce from 5.03(2) to 3.07(1) Å and 5.04(3) to 2.94(1) Å, respectively, from 270 to 100 K (Fig. 7, Table S4†). From 270 K to 198 K, the total CO2 occupancy increases from 0.5 to 0.92, which was retained to 100 K. From 270 K to 198 K, the ratio of  decreases from 74(1)% to 53(1)%, and that of

decreases from 74(1)% to 53(1)%, and that of  increases from 26(1) to 47(1)%. Below 198 K, the ratio of

increases from 26(1) to 47(1)%. Below 198 K, the ratio of  increase slightly to 57(1)% and that of

increase slightly to 57(1)% and that of  decreases to 43(1)%.

decreases to 43(1)%.  is in a cross-tunnel mode at 270 K.

is in a cross-tunnel mode at 270 K.  molecules are parallel to the pyridine ring at 270 K, and rotate to be almost parallel to

molecules are parallel to the pyridine ring at 270 K, and rotate to be almost parallel to  with reducing temperature. From 270 K to 198 K, the Ea of

with reducing temperature. From 270 K to 198 K, the Ea of  and

and  are 2.068 and –2.842 kJ mol–1, respectively, and from 198 K to 100 K, the Ea values are –0.125 kJ mol–1 and 0.154 kJ mol–1 for

are 2.068 and –2.842 kJ mol–1, respectively, and from 198 K to 100 K, the Ea values are –0.125 kJ mol–1 and 0.154 kJ mol–1 for  and

and  , respectively. The Ea for adsorbed CO2 molecules in MFM-305 is significantly higher than that of MFM-305-CH3 at 270–198 K, indicating the formation of stronger host–guest interactions in MFM-305. This study confirms that the host–guest interaction between functional groups and CO2 molecules in these two MOFs follows the trend of hydroxyl/pyridyl groups–CO2 > CO2–CO2 > methyl group–CO2. Thus, the simultaneous enhancements of adsorption capacity and host–guest binding affinity upon pore modification on going from MFM-305-CH3 to MFM-305 can be fully rationalised.

, respectively. The Ea for adsorbed CO2 molecules in MFM-305 is significantly higher than that of MFM-305-CH3 at 270–198 K, indicating the formation of stronger host–guest interactions in MFM-305. This study confirms that the host–guest interaction between functional groups and CO2 molecules in these two MOFs follows the trend of hydroxyl/pyridyl groups–CO2 > CO2–CO2 > methyl group–CO2. Thus, the simultaneous enhancements of adsorption capacity and host–guest binding affinity upon pore modification on going from MFM-305-CH3 to MFM-305 can be fully rationalised.

The crystal structure of CO2-loaded MFM-305-CH3 was also determined at 7 K by neutron powder diffraction which confirms retention of the space group I41/amd. Interestingly, a completely new structure was resolved where only one binding domain for adsorbed CO2 was located near the methyl group (Fig. S34†). The adsorbed CO2 molecules are disordered about a 2-fold rotation axis and in a cross-tunnel mode interacting with the methyl group with a C[combining low line]H3···O[combining low line]CO distance of 3.58(2) Å. CO2 also binds to the pyridinium–hydrogen atoms with a CH[combining low line]···O[combining low line]CO distance at 3.08(2) Å. This result confirms the significant impact of temperature on the binding sites and orientation of adsorbed CO2 molecules in MFM-305-CH3.

Conclusions

We have reported here the synthesis and characterisation of porous MFM-305-CH3, and its transformation via post-synthetic demethylation to give the isostructural, neutral MFM-305. The post-synthetic modification has enabled direct modulation of the pore environment, including changes in charge distribution and accessible functional groups. Significantly, MFM-305 shows simultaneously enhanced CO2 and SO2 uptake and CO2/N2 and SO2/CO2 selectivities over MFM-305-CH3; these two factors are widely known to display a trade-off in porous materials. A comprehensive investigation of the host–guest binding using a combinations of synchrotron X-ray and neutron powder diffraction, INS, 2H NMR and IR spectroscopy and modelling has unambiguously revealed the role of Lewis acid, Lewis base, chloride ions, methyl and hydroxyl groups in the supramolecular binding of guest molecules within the pores of both MOFs. Considering that these two MOFs have similar pore shape and size, the distinct binding mechanisms to guest molecules between these two samples is a direct result of the charge modulation. We have also confirmed that post-synthetic modification via dealkylation of the as-synthesised metal–organic framework is a powerful route to the synthesis of materials incorporating active polar groups, in this case a free pyridyl N-donor. Thus, deprotection of the as-synthesized MOF allows the synthesis of materials that cannot as yet, in our hands, be synthesized directly.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank EPSRC (EP/I011870 to MS), ERC (AdG 742041 to MS) and University of Manchester for funding. We are especially grateful to STFC and the ISIS Neutron Facility for access to the Beamlines TOSCA and WISH, to Diamond Light Source for access to Beamlines I11 and B22 and to ORNL for access to Beamline VISION. LL thanks for the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program from China and the Sino-British Fellowship (Royal Society) for support. The computing resources were made available through the VirtuES and ICEMAN projects, funded by Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at ORNL. DIK and AGS acknowledge financial support within the framework of the budget project #AAAA-A17-117041710084-2 of the Boreskov Institute of Catalysis.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Synthetic details, structural data, figures, PXRD patterns, TGA, IR spectroscopic and sorption analyses. This material is available in the online version of paper. Correspondence of requests for materials should be addressed to S. Y. and M. S. CCDC 1580818–1580823, 1580825–1580829, 1580831, 1580832, 1580833, 1580834. For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: 10.1039/c8sc01959b

References

- Monastersky R. Nature. 2013;497:13–14. doi: 10.1038/497013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. J., van Aardenne J., Klimont Z., Andres R. J., Volke A., Arias S. D. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:1101–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar N. L., Kaushik S. C., Kothari S. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2011;15:1513–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Songolzadeh M., Soleimani M., Ravanchi M. T., Songolzadeh R. Sci. World J. 2014;2014:34. [Google Scholar]

- Rochelle G. T. Science. 2009;325:1652–1654. doi: 10.1126/science.1176731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G. K., Wang J. J., Zhang S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:4307–4339. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00462d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R. K., Jozewicz W. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2001;51:1676–1688. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2001.10464387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H., Cordova K. E., O'Keeffe M., Yaghi O. M. Science. 2013;341:974. doi: 10.1126/science.1230444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H. X., Grunder S., Cordova K. E., Valente C., Furukawa H., Hmadeh M., Gandara F., Whalley A. C., Liu Z., Asahina S., Kazumori H., O'Keeffe M., Terasaki O., Stoddart J. F., Yaghi O. M. Science. 2012;336:1018–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1220131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M., Tanaka D., Horike S., Sakamoto H., Nakamura K., Takashima Y., Hijikata Y., Yanai N., Kim J., Kato K., Kubota Y., Takata M., Kitagawa S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10336–10337. doi: 10.1021/ja900373v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X. Q., Scott E., Ding W., Mason J. A., Long J. R., Reimer J. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14341–14344. doi: 10.1021/ja306822p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H. X., Doonan C. J., Furukawa H., Ferreira R. B., Towne J., Knobler C. B., Wang B., Yaghi O. M. Science. 2010;327:846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1181761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z. Z., Godfrey H. G. W., da Silva I., Cheng Y. Q., Savage M., Tuna F., McInnes E. J. L., Teat S. J., Gagnon K. J., Frogley M. D., Manuel P., Rudic S., Ramirez-Cuesta A. J., Easun T. L., Yang S. H., Schröder M. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14212. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidhyanathan R., Iremonger S. S., Shimizu G. K. H., Boyd P. G., Alavi S., Woo T. K. Science. 2010;330:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1194237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molavi H., Eskandari A., Shojaei A., Mousavi S. A. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018;257:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fracaroli A. M., Siman P., Nagib D. A., Suzuki M., Furukawa H., Toste F. D., Yaghi O. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8352–8355. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Luo Y. P., Sun L., Pu S., Fang M., Yuan R. X., Du H. B. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:8614–8621. doi: 10.1039/c6dt00992a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm H., Ha H., Kim S., Jung B., Park M. H., Kim Y., Heo J., Kim M. CrystEngComm. 2015;17:5644–5650. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., Fu Z. Y., Chen H. J., Liu C. C., Liao S. J., Dai J. C. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:8114–8116. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33823h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Thallapally P. K., McGrail B. P., Brown D. R., Liu J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2308–2322. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15221a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. H., Sun J. L., Ramirez-Cuesta A. J., Callear S. K., David W. I. F., Anderson D. P., Newby R., Blake A. J., Parker J. E., Tang C. C., Schröder M. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:887–894. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage M., Cheng Y. G., Easun T. L., Eyley J. E., Argent S. P., Warren M. R., Lewis W., Murray C., Tang C. C., Frogley M. D., Cinque G., Sun J. L., Rudic S., Murder R. T., Benham M. J., Fitch A. N., Blake A. J., Ramirez-Cuesta A. J., Yang S. H., Schröder M. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:8705–8711. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:970–1000. doi: 10.1021/cr200179u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C., Kong C. L., Chen L. RSC Adv. 2016;6:32598–32614. [Google Scholar]

- Islamoglu T., Goswami S., Li Z. Y., Howarth A. J., Farha O. K., Hupp J. T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:805–813. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X. L., Yang Q. W., Yang L. F., Krishna R., Zhang Z. G., Bao Z. B., Wu H., Ren Q. L., Zhou W., Chen B. L., Xing H. B. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1606929. doi: 10.1002/adma.201606929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K., Canepa P., Gong Q. H., Liu J., Johnson D. H., Dyevoich A., Thallapally P. K., Thonhauser T., Li J., Chabal Y. J. Chem. Mater. 2013;25:4653–4662. [Google Scholar]

- Luo F., Yan C. S., Dang L. L., Krishna R., Zhou W., Wu H., Dong X. L., Han Y., Hu T. L., O'Keeffe M., Wang L. L., Luo M. B., Lin R. B., Chen B. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5678–5684. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J., Geib S. J., Rosi N. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:38–39. doi: 10.1021/ja909169x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tome L. C., Marrucho I. M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:2785–2824. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00510h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. Z., Han B. X., Gao H. X., Liu Z. M., Jiang T., Huang J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:2415–2417. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Lu Y. X., Peng C. J., Hu J., Liu H. L., Hu Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:3949–3958. doi: 10.1021/jp111194k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Roberts J. M., Farha O. K., Sarjeant A. A., Scheidt K. A., Hupp J. T. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:9971–9973. doi: 10.1021/ic901174p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinsch H., van der Veen M. A., Gil B., Marszalek B., Verbiest T., de Vos D., Stock N. Chem. Mater. 2013;25:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. L. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan V., Jacob W., Mukherjee J., Mukherjee R. CrystEngComm. 2004;6:396–400. [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Li L., Zhang J. Y., Han X. R., Jiang L., Li F. W., Su C. Y. Chem. Mater. 2012;24:480–485. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth G., Kawazoe K. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1983;16:470–475. [Google Scholar]

- Demessence A., D'Alessandro D. M., Foo M. L., Long J. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8784–8785. doi: 10.1021/ja903411w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. L., Prausnitz J. M. AIChE J. 1965;11:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka K., Mizuse S. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;87:3647–3652. [Google Scholar]

- Simon A., Peters K. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1980;36:2750–2751. [Google Scholar]

- Post B., Schwartz R. S., Fankuchen I. Acta Crystallogr. 1952;5:372–374. [Google Scholar]

- Katcka M., Urbanski T. Bull. Acad. Pol. Sci., Ser. Sci. Tech. 1964;9:615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokolov D. I., Stepanov A. G., Jobic H. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:27512–27520. [Google Scholar]

- Hoatson G. L., Vold R. L., Tse T. Y. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;100:4756–4765. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C., Kong C. L., Chen L. RSC Adv. 2012;2:6417–6419. [Google Scholar]

- Caskey S. R., Wong-Foy A. G., Matzger A. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10870–10871. doi: 10.1021/ja8036096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C., Yan Q. J., Kong C. L., Chen L. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1859. doi: 10.1038/srep01859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Albelo L. M., López-Maya E., Hamad S., Ruiz-Salvador A. R., Calero S., Navarro J. A. R. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14457. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.