Abstract

Background

The role of dietary patterns in the prevention of unipolar depression has been analyzed in several epidemiological studies. The primary aims of this study are to determine the effectiveness of an extra-olive oil-enriched Mediterranean diet in reducing the recurrence of depression and improving the symptoms of this condition.

Methods

Multicenter, two-arm, parallel-group clinical trial. Arm 1, extra-virgin olive oil Mediterranean diet; Arm 2, control group without nutritional intervention. Dieticians are in charge of the nutritional intervention and regular contact with the participants. Contacts are made through our web platform (https://predidep.es/participantes/) or by phone. Recurrence of depression is assessed by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists through clinical evaluations (semi-structured clinical interviews: Spanish SCID-I). Depressive symptoms are assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory. Information on quality of life, level of physical activity, dietary habits, and blood, urine and stool samples are collected after the subject has agreed to participate in the study and once a year.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the PREDI-DEP trial is the first ongoing randomized clinical trial designed to assess the role of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention of recurrent depression. It could be a cost-effective approach to avoid recurrence and improve the quality of life of these patients.

Trial registration

The study has been prospectively registered in the U.S. National Library of Medicine (https://clinicaltrials.gov) with NCT number: NCT03081065.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12888-019-2036-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mediterranean diet, Extra-virgin olive oil, Recurrence of depression, Clinical trial

Background

Unipolar depression is one of the leading global causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [1] and, in 2016, one of the leading causes of Years Lived with Disability (YLD) [2].

Prevention of depression recurrence is an essential goal in the management of depressive patients. Pharmacological treatment strategies are common to help prevent the risk of recurrence, as well as other alternatives, e.g., psychological interventions, which have shown promising outcomes [3].

Besides pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches, other interventions based on lifestyle changes, e.g., diet, physical activity, or alcohol and drug limitations, can be helpful can be helpful as part of the treatment of these patients. A body of research suggests the beneficial role of these factors in the etiopathogenesis of the condition and their potential utility for its management [4, 5].

Over the last years, several epidemiological studies have analyzed the role of dietary patterns, foods, food groups and nutrients, as factors that can help prevent unipolar depression. A recent systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies shows that higher quality diets associate with lower risks of developing depressive symptoms, although the authors believe that this hypothesis has to be further tested with prospective studies and randomized controlled trials [6]. Being an emerging promising field of research within nutritional epidemiology, to date there is still scarce evidence [7–9]. One of the dietary factors that has been inversely associated with depression is the adherence to the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern (MDP). Several cohort studies report an inverse relationship between following this healthy dietary pattern and the risk of developing depression [10–12]. Furthermore, two clinical trials carried out with depressive patients found significant improvement regarding depressive symptoms in patients assigned to the MDP [13, 14].

To our knowledge there are not clinical trials specifically designed to assess the role of a nutritional intervention based on the Mediterranean diet in the prevention of depression recurrence.

Objectives

The primary objective of this study, the PREDI-DEP trial, is to investigate the effectiveness of following an extra-virgin olive oil-enriched Mediterranean diet with the risk of depression recurrence and improvement of residual depressive symptoms in participants with previous episodes of mayor depression. The secondary objectives are to analyze the effect of the Mediterranean nutritional intervention in the quality of life, various biochemical parameters and changes on the microbiota of the participants. We also aim to test the relationship between the nutritional intervention with an extra-virgin olive oil Mediterranean diet with the reduction in the risk of medical and psychiatric comorbidities in patients with a previous diagnosis of unipolar depressive disorder.

Materials and methods

Design

Multicenter, two-arm, parallel-group clinical trial. One group of patients (arm 1) is assigned to a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil and the second group (control) (arm 2) has no nutritional intervention. The participants are recruited from four centers across Spain: Hospital Dr. Negrín (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Clínica Universidad de Navarra (Pamplona), Hospital Universitario (Vitoria), and Clínica Dr. Chiclana (Madrid). The intervention period lasted two years.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were established after an exhaustive review of the scientific literature and consensus among all participating psychiatric and clinical psychologists. Study subjects are aged ≥18 years, has had a previous major depressive episode within the last five years and are in a stage of total or partial remission within the last six months, based on DSM-5 criteria. One participant who has undergone a single depression episode is included for every three participants who had undergone two or more episodes.

Exclusion criteria

Table 1 shows the exclusion criteria in the PREDI-DEP trial:

Table 1.

Exclusion criteria in the PREDI-DEP trial

| 1. Presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders (current mania/hypomania or a history of bipolar disorder, psychosis or schizophrenia, predominant anxiety disorder, primary personality disorder, substance abuse or eating disorder) | |

| 2. Suspicion of depression (Score > 18 in Beck Depression Inventory) [16] | |

| 3. Participants with severe medical conditions with low survival | |

| 4. Participants with history of food allergy with hypersensitivity to any of the components of olive oil or nuts, presence of disorders of chewing or swallowing or a low predicted likelihood of changing dietary habits according to the Prochaska and DiClemente stages of change model [35] | |

| 5. Institutionalized patients and those participants who lack autonomy |

Patient recruitment

In a first phase of the selection process, we extract names of potential participants from the clinical records of the hospitals or health centers who are willing to collaborate with the study. Next, the participating psychologists and psychiatrists review the clinical records individually to identify the subjects that comply with the inclusion criteria. The potential participants are contacted by phone or during a clinical visit. When a candidate agrees to participate, a face-to-face interview with the specialist is carried out to exclude participants who do not meet the criteria. Besides the semi-structured clinical interview (Spanish SCID-I) [15], participants also self-complete the Beck Depression Inventory to assess depressive symptoms [16]. Information about the participant is completed with questions from the eligibility questionnaire, such as medical conditions or problems related with the adherence to the Mediterranean diet. During the first visit, participants receive a brief explanation of the study, are informed that are going to be given extra-virgin olive oil for the duration of the trial at no cost, and a signed informed consent is obtained. All study participants are asked to provide blood samples (previous appointment with the hospital) and a subgroup of participants is instructed to also provide urine samples (recruitment centers: Vitoria, Pamplona) and stool samples (recruitment center: Vitoria).

Randomization

Study participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups (Mediterranean diet or control) once their data are included in a centralized computer system by the specialists. Various stratification factors are considered for the randomization, sex, age group (< 65 years or ≥ 65 years) and recruitment center. At baseline, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are blinded to the allocation of the participants, following the CONSORT guidelines for randomized trials to prevent selection biases.

Intervention with the Mediterranean diet and control group

Full-time registered dietitians with experience in the PREDIMED trial are responsible for the dietary intervention in the PREDI-DEP study. The PREDIMED trial is a landmark trial of intervention with a Mediterranean diet in participants at high risk of cardiovascular disease [17, 18]. The methodology in PREDI-DEP is similar to that in PREDIMED.

Participants allocated to the Mediterranean diet receive intensive training on Mediterranean diet and supplemental foods (Table 2), as well as extra-virgin olive oil (one liter of extra-virgin olive oil rich in polyphenols every two weeks), at no cost. The authors have no conflict of interest with any food company.

Table 2.

Intervention with Mediterranean diet

| Intervention | Periodicity | Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Free food supply | Quarterly | Collected by participants in medical centers |

| Book and information regarding Mediterranean Diet | Initial | Collected by participants in medical centers |

| Buying foods list, plan of meals, cooking recipes, menus | Quarterly | Collected by participants in medical centers |

| Compliance degree, personalized goal achivement | Quarterly | Telephone |

| Mediterranean Diet news | Monthly | Web/e-mail |

| Clarification of doubts, suggestions | Any moment | Any instrument |

At the beginning of the trial, the dieticians thoroughly explain the reasons to follow a Mediterranean diet to each participant and negotiate changes in his/her diet, working with the subject to determine what he or she considers an attainable goal. The dietician does this every three months by calling the participant over the phone. To assess adherence to the Mediterranean diet and enhance future adherence (Additional file 1), the dietitians use a validated 14-point Mediterranean Diet Assessment Screener (MEDAS) [19], which was employed in the PREDIMED trial.

Every three months the participants receive written material with information on key Mediterranean foods and seasonal shopping lists, menus and specific recipes for a typical week. This material is discussed in detail with the dietitians.

The website developed for this study (https://predidep.es/participantes/) is updated monthly with news related to the Mediterranean diet and its health effects. The dieticians take into account any doubt or suggestion made by the participants at any time of the intervention period.

No nutritional intervention is employed with the control group. These participants have an email and access to the website of the project, but with limitations on the contents related with the intervention. To prevent these subjects from withdrawing from a study an incentive at trial termination is offered.

Data collection and measurements

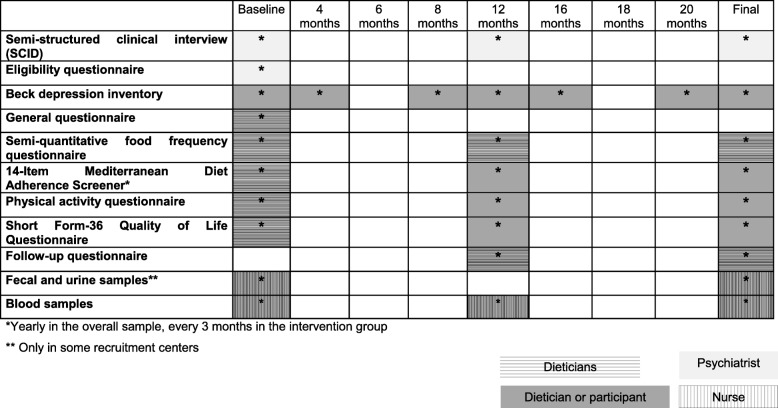

Table 3 shows the variables, their corresponding time points and the researchers implicated in the collection of the data.

Table 3.

Exposures and outcomes measures, timepoints and researchers implicated in the collection of data

The dieticians are in charge of the nutritional interventions (Mediterranean diet), as well as for the regular contact and follow-up of the participants. Contacts are made using current technologies such as our web platform (https://predidep.es/participantes/), phone calls, or email. When a participant is not familiarized with these technologies, the dieticians use postal mail to send all the information.

Assessment of exposure

Baseline information

The dieticians have the first contact with the participants over the phone to inform them in which arm they have been allocated and give instructions to the subjects who have been assigned to the Mediterranean diet as where and when to collect the food supply. Moreover, the dieticians complete the information for each participant through: 1) a general questionnaire; 2) a physical activity questionnaire; 3) a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ); 3) the 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), and 4) the Short Form-36 Quality of Life Questionnaire (SF-36).

Dietary assessment

Diet is assessed with a semi-quantitative FFQ validated in Spain [20]. The questionnaire covers 137 foods and is completed at baseline and yearly by the dietitians over the phone. The estimation of nutrient intake will be calculated as frequency multiplied by nutrient composition of the specified portion for each food item, using an ad hoc computer program developed specifically for this purpose. The repeated collection of dietary data allows us to use the PREDI-DEP trial as a unique setting for subsequent cohort studies, analyzed as a prospective observational follow-up study with repeated measurements of diet, thus improving the quality of our dietary assessment.

Changes in adherence to the Mediterranean diet is assessed through the MEDAS questionnaire at baseline and yearly in the control group and every three months in the Mediterranean diet group.

Assessment of the physical activity

Physical activity is assessed using a validated physical activity questionnaire with seventeen activities [21]. Leisure activities will be computed by assigning an equivalent metabolic score to each activity, multiplied by the time spent in each one and adding up all activities. The baseline questionnaire is completed over the phone. Yearly, participants complete the same questionnaire using the website of the project or by phone with the help of the dietician if they request it.

Assessment of other variables

Information regarding socioeconomic (educational level, employment and marital status), anthropometric (weight, height, and waist and hip circumferences), life-style (tobacco or history of illegal drug use), and medical characteristics of the participants, including medication, family history of mental disorders or the use of psychotherapy or relaxation techniques are obtained from the general questionnaire at baseline. This information is updated on a yearly basis using follow-up questionnaires.

Outcome assessment of the nutritional intervention

Recurrence of depression

The clinical evaluations by specialists are limited to yearly follow-up visits that consist of the same examinations performed at baseline. If any suspicion of depression is detected through the Beck depression inventory or the subject him/herself communicates it, the specialist arranges an appointment with the participant. Specialists review the clinical records of participants lost to follow-up in order to assess possible cases of recurrence of depression not reported by the participants or detected by their specialists at follow-up.

Assessment of depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms are assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory validated in Spain, which includes 21 questions with four possible answers sorted according to symptom severity [16].

Every four months, the participants complete this questionnaire over the phone with the aid of the dietitians or by themselves through the website. Exceptionally, at the beginning of the study or once a year the inventory is completed in the psychiatrist’s consulting room.

Quality of life assessment

Quality of life is assessed at baseline and yearly (over the phone or through the website) with the Spanish version of the SF-36 [22], a general, widely used, and thoroughly validated health scale. It contains 36 items that measure eight multi-item domains of health status: 1) physical functioning, 2) role limitations due to physical health problems (role-physical), 3) bodily pain, 4) general health perceptions, 5) vitality, 6) social functioning, 7) role limitations due to emotional problems (role-emotional), and 8) mental health. Domains 1 to 4 of the questionnaire deal with physical aspects, while domains 5 to 8 measure psychological features. For each parameter, scores will be coded, added up and transformed into a scale from 0 (the worst possible condition) to 100 (the best possible condition). For bodily pain domain a score of 100 implied complete tolerance or absence of pain.

Biological samples

Blood, urine and stool samples are collected at baseline and yearly during medical visits. EDTA plasma tubes, buffy coat, and serum are collected and aliquots are kept at − 80 °C. All the samples are correctly identified and labeled with an alphanumeric code.

Biological compliance markers (plasma proportions of oleic and α-linolenic acid and urinary levels of tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, resveratrol and ethanol) will be measured randomly in participants from the two arms of the trial at baseline and at the end of the study.

Sample size and data analyses

The original sample size calculation indicated that 250 people per group were required (assuming an attrition of 5%) to provide a statistical power of 80% for detecting a relative risk reduction of 30% in the Mediterranean diet group versus the control group for a two-year follow-up period. The assumed recurrence rate was 50% for the control group and 35% for the group assigned to the Mediterranean diet. The relative risk reduction of 30% was slightly lower than the observed in the SUN cohort study. In this latter study, we found a 40% risk reduction of depression comparing extreme quintiles of adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Score [23] and the observed among diabetic participants of the PREDIMED trial after three years of intervention with the Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts [24].

A researcher blinded to the conditions of the intervention will carry out the analysis of the data. Intention-to-treat analysis will be done. For each participant we will compute person-years of follow-up from the study inclusion date to the date of recurrence of the depression or study termination, whichever comes first.

Log Rank analysis will be used to assess the effect of the intervention on the risk of depression recurrence. If distribution differences of baseline characteristics are detected, the Cox proportional-hazards regression models will be used to check by recruitment center, age group and sex, and adjusting for possible confounding factors (educational level, marital status, prevalence of diseases, body mass index, tobacco use, leisure-time physical activity, alcohol intake, total energy intake, type, dose and use of antidepressants, psychotherapy, presence, number, and time since last of depressive symptoms/episodes, and family history of mental disorders). Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) will be calculated considering the control group as reference.

We will also carry out a protocol analysis [25]. Categories of adherence to the Mediterranean diet will be defined using information from the FFQ and MEDAS, and Cox regression models will be fitted. Marginal structural models (inverse probability of exposure-weighted estimators) will be fitted to exposure measures that vary over time [26]. Finally, to examine quantitative variables such adherence to the Mediterranean diet scorings [27], other analysis will be explored, e.g., smoothing splines and regression analysis based on fractional polynomials [28, 29].

Changes in residual depressive symptoms, quality of life or biochemical parameters were evaluated through Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models and will be adjusted for possible confounding factors and baseline values of depressive symptoms, quality of life or each biochemical parameter, respectively.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses will be done under different assumptions. To assess a possible interaction between the intervention and some variables (e.g., age, sex or the presence of non-communicable diseases), product terms will be introduced in the multivariable models. P values for the interaction will be calculated using the log-likelihood ratio test.

Multiple imputation will be employed for handling missing data [30, 31].

Monitoring of Data

Three independent clinical trial experts in Nutrition, Psychiatry and Statistics made up the data monitoring committee (DMC). They will hold an annual meeting to review the implementation of the protocol, monitor trial progress, and recommend the continuation or termination of the study based on safety, outstanding benefit, or futility criteria.

A web-based system of data access was created (https://predidep.es/participantes/), from where authorized investigators and the coordinator of the trial can download forms and datasets. For privacy and security, an ID and password are required to access the data and the forms.

Quality control reports are generated for key aspects of the trial, e.g., digit preference and variability. We perform checks on missing and/or inconsistencies of the data. Following data entry, cross-form edit checks are done. Audits are carried out periodically to detect unresolved problems. Standardized edit reports summarizing database problems reassures the quality of the data.

Discussion

Recent studies have assessed the role of the Mediterranean diet in patients with depressive disorders. Jacka et al. reported improvements in depressive symptoms in a sample of 56 depressive patients after 12 weeks of a dietary intervention with a Mediterranean diet in comparison to a social intervention [13]. Similarly, Parletta et al. observed reduced depression and higher quality of life among participants with higher MedDiet scorings in a clinical trial of 95 depressive patients based on the intervention with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with fish [14]. However, these small trials did not evaluate the long-term effect on depression of the Mediterranean diet. Moreover, the aim of the trials was to assess the role of the Mediterranean diet in the treatment of depression and not on its prevention.

The MooDFOOD prevention trial examines the feasibility and effectiveness of two different nutritional strategies (multi-nutrient supplementation and food-related behavioral change therapy). However, it does not examine the effect of a Mediterranean diet intervention in preventing depression in subjects with overweight and have elevated depressive symptoms, but with no current -or in the last six months- criteria for an episode of major depressive disorder [32].

Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, the PREDI-DEP clinical trial is the first randomized clinical trial designed to assess the role of a MDP in the prevention of recurrent depression. Preventing recurrence of depression is one of the priorities in the management of patients with depression, particularly when the number of relapses is high. Whereas the risk of recurrence is approximately 40–60% in patients with a unique depression episode, this risk raises to 90% in patients with three or more previous episodes [33, 34]. Our study provides essential evidence regarding the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of improving the diet based on a Mediterranean eating pattern for preventing the recurrence of depression and improving the quality of life of patients with previous episodes of depression.

Additional file

14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS). Description of the MEDAS questionnaire. (DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the PREDI-DEP study participants.

Funding

This study is externally funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (ISCIII), PI16/01274. The Interprofesional del Aceite de Oliva-Aceites de Oliva de España (Madrid, Spain) donated the olive oil used in the study.

None of the funding sources played a role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.

Abbreviations

- CIs

Confidence Intervals

- DALYs

Disability-Adjusted Life Years

- DMC

Data Monitoring Committee

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equation

- HRs

Hazard Ratios

- MEDAS

Mediterranean Diet Assessment Screener

- PREDIMED

Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (Prevention with the Mediterranean Diet)

- SCID-I

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

- SF-36

Short Form (36) Health Survey

- SUN

Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (University of Navarra Follow-up Project)

- YLDs

Years Lived with Disability

Authors’ contributions

ASV: Acquisition of funding, study coordination, and manuscript drafting. ASV, PM, AGP, CCA, FL, JP, FO and JLHF: substantial contributions to conception and design of the trial. BCS, PM, CCA, CC, FL, MFR, PVP, SN, RVP, YA, MJCC, and JLHF: substantial contributions to acquisition of data. All authors revised the draft critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the last version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Research Ethics Committees of Hospital Dr. Negrín of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Clinica Universidad de Navarra of Pamplona, and Hospital Universitario of Vitoria approved this study.

The psychiatrists and clinical psychologists of the project obtain a general informed consent for the collection and use of the data and biological specimens of the participants at the beginning of the trial. The informed consent includes permission to publish the data of the patients.

Future publications of clinical data of the participants does not compromise anonymity or confidentiality or breach local data protection laws.

This study was carried out following the CONSORT guidelines and the SPIRIT 2013 Checklist.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

A. Sánchez-Villegas, Email: almudena.sanchez@ulpgc.es

B. Cabrera-Suárez, Email: beatriz_mcs@hotmail.com

P. Molero, Email: pmolero@unav.es

A. González-Pinto, Email: anamaria.gonzalez-pintoarrillaga@osakidetza.eus

C. Chiclana-Actis, Email: carloschiclana@gmail.com

C. Cabrera, Email: cabreraclaudio@hotmail.com

F. Lahortiga-Ramos, Email: flahortiga@unav.es

M. Florido-Rodríguez, Email: mfloridorodriguez@gmail.com

P. Vega-Pérez, Email: patricia.vegaperez@osakidetza.eus

R. Vega-Pérez, Email: sarivega@cop.es

J. Pla, Email: jpla@unav.es

M. J. Calviño-Cabada, Email: setina007@hotmail.com

F. Ortuño, Email: fortuno@unav.es

S. Navarro, Email: santinavarro77@hotmail.com

Y. Almeida, Email: yalmeida9@hotmail.com

J. L. Hernández-Fleta, Email: jherfle@gmail.com

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2197–2123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jonge M, Bockting CL, Kikkert MJ, Bosmans JE, Dekker JJ. Preventive cognitive therapy versus treatment as usual in preventing recurrence of depression: protocol of a multi-centered randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:139. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berk M, Sarris J, Coulson CE, Jacka FN. Lifestyle management of unipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2013;443:38–54. doi: 10.1111/acps.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopresti AL, Hood SD, Drummond PD. A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):12–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molendijk M, Molero P, Ortuño Sánchez-Pedreño F, Van der Does W, Angel Martínez-González M. Diet quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-González MA, Sánchez-Villegas A. Food patterns and the prevention of depression. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(2):139–146. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Opie RS, Itsiopoulos C, Parletta N, Sánchez-Villegas A, Akbaraly TN, Ruusunen A, et al. Dietary recommendations for the prevention of depression. Nutr Neurosci. 2017;20(3):161–171. doi: 10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarris J, Alan C, Logan BA, Akbaraly TN, Amminger GP, Balanzá-Martínez V, et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):271–274. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sánchez-Villegas A, Henríquez-Sánchez P, Ruiz-Canela M, Lahortiga F, Molero P, Toledo E, et al. A longitudinal analysis of diet quality scores and the risk of incident depression in the SUN Project. BMC Med. 2015;13:197. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0428-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeulen E, Stronks K, Visser M, Brouwer IA, Schene AH, Mocking RJ, et al. The association between dietary patterns derived by reduced rank regression and depressive symptoms over time: the Invecchiare in chianti (InCHIANTI) study. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(12):2145–2153. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516001318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adjibade M, Assmann KE, Andreeva VA, Lemogne C, Hercberg S, Galan P, et al. Prospective association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of depressive symptoms in the French SU.VI.MAX cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2008;57(3):1225–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parletta N, Zarnowiecki D, Cho J, Wilson A, Bogomolova S, Villani A, et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci. 2017:1–14. 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320. [Epub ahead of print]. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Opie RS, O'Neil A, Jacka FN, Pizzinga J, Itsiopoulos C. A modified Mediterranean dietary intervention for adults with major depression: Dietary protocol and feasibility data from the SMILES trial. Nutr Neurosci. 2018;21(7):487–501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Entrevista Clínica Estructurada para los Trastornos del Eje I del DSM-IV, Versión Clínica (SCID-I-VC) Barcelona: Masson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanz J, Perdigón AL, Vázquez C. Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 2. Propiedades psicométricas en población general. Clínica y Salud. 2003;1(3):249–280. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, Estruch R, Corella D, Fitó M, Ros E, et al. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: insights from the PREDIMED study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;58(1):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Validation of a short screener for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011;141:1140–1145. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández-Ballart JD, Pinol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. 2009;103(12):1808–1816. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez-González MA, López-Fontana C, Varo JJ, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez JA. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the Nurses’ health study and the health Professionals’ follow-up study. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(7):920–927. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Rajmil L, Rebollo P, Permanyer-Miralda G, Quintana JM, et al. El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 español: una década de experiencia y nuevos desarrollos. Gac Sanit. 2005;19:135–150. doi: 10.1157/13074369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sánchez-Villegas A, Delgado-Rodríguez M, Alonso A, Schlatter J, Lahortiga F, Serra Majem L, et al. Association of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with the incidence of depression: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra/University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1090–1098. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sánchez-Villegas A, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, Corella D, Covas MI, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: the PREDIMED randomized trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:208. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porta M, Bonet C, Cobo E. Discordance between reported intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robins JM, Hernán M, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29(9):1037–1057. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. MFP: multivariable model-building with fractional polynomials. En: Royston P, editor. Multivariable model-building: a pragmatic approach to regression analysis based on fractional polynomials for modelling continuous variables. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. pp. 79–96.

- 30.Groenwold RH, Donders AR, Roes KC, Harrell FE, Jr, Moons KG. Dealing with missing outcome data in randomized trials and observational studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:210–217. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2ª ed. Hoboken: J.W. Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roca M, Kohls E, Gili M, Watkins E, Owens M, Hegerl U, et al. Prevention of depression through nutritional strategies in high-risk persons: rationale and design of the MooDFOOD prevention trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:192. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0900-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee HB, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:513–520. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–233. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nigg CR, Burbank PM, Padula C, Dufresne R, Rossi JS, Velicer WF, et al. Stages of change across ten health risk behaviors for older adults. Gerontologist. 1999;39(4):473–482. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS). Description of the MEDAS questionnaire. (DOCX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.