Abstract

The long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) Maternally Expressed Gene 3 (Meg3) is encoded within the imprinted Dlk1-Meg3 gene locus and is only maternally expressed. Meg3 has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of cellular proliferation and functions as a tumor suppressor in numerous tissues. Meg3 is highly expressed in mouse adult hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and strongly down-regulated in early progenitors. To address its functional role in HSCs, we used MxCre to conditionally delete Meg3 in the adult bone marrow of Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice. We performed extensive in vitro and in vivo analyses of mice carrying a Meg3 deficient blood system, but neither observed impaired hematopoiesis during homeostatic conditions nor upon serial transplantation. Furthermore, we analyzed VavCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice, in which Meg3 was deleted in the embryonic hematopoietic system and unexpectedly this did neither generate any hematopoietic defects. In response to interferon-mediated stimulation, Meg3 deficient adult HSCs responded highly similar compared to controls. Taken together, we report the finding, that the highly expressed imprinted lncRNA Meg3 is dispensable for the function of HSCs during homeostasis and in response to stress mediators as well as for serial reconstitution of the blood system in vivo.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are characterized by their unique self-renewal capacity and multipotency1. As most mature blood cells are relatively short-lived, there is a constant need for the replenishment of functional effector cells. Along a hematopoietic cascade, HSCs first give rise to multipotent progenitor populations (MPPs) which differentiate into committed progenitors and will eventually give rise to mature effector cells2. In homeostasis, HSCs are characterized by a deeply quiescent cell status, called dormancy, protecting them from DNA damage and preserving their genomic integrity2,3. During stress response, such as upon infection and inflammation, HSCs exit the G0 dormant state and enter the cell division cycle4,5. The unique characteristics and the potential of HSCs have long been known2,6, however, only recently molecular expression signatures, signaling pathways and cell surface markers were identified by state-of-the-art OMICs analyses on a population and at the single-cell level7–9. Especially genes that show a very high and specific expression in HSCs are of major interest, as these genes are potential candidates involved in controlling HSC function, self-renewal and multipotency. Besides protein-coding genes, multiple long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, >200 nucleotides) were identified to be expressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitors and are known to play functional roles during normal and malignant hematopoiesis such as Lnc-HSC-2 and Xist10–12. One of the genes we and others identified as very highly and specifically expressed in HSCs is the lncRNA Maternally Expressed Gene 3 (Meg3)8,9,13.

Meg3, also known as gene trap locus 2 (Gtl2), is a lncRNA encoded in the imprinted Dlk1-Meg3 gene locus14,15. The cis-elements regulating Meg3 expression consist of two differentially methylated regions (DMRs), intergenic (IG)-DMR and Meg3-DMR, respectively16. Meg3, together with multiple non-coding RNAs and small non-coding RNAs, including the largest mammalian miRNA mega-cluster, is expressed from the maternally inherited allele only. IG-DMR and Meg3-DMR are unmethylated on the maternal allele, whereas they are methylated on the paternally inherited allele, from which three protein-coding genes (Dlk1, Rtl1 and Dio3) are expressed16. Meg3 gene deletion, either by targeting of Meg3 or IG-DMR, is embryonically lethal and different phenotypes are observed depending on the knock-out (KO) model17–19. In addition, Meg3 seems to act as a tumor suppressor and as an important regulator of cellular proliferation14,15. Interestingly, the imprinted gene network was described to be predominantly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells, including Meg320. Moreover, Qian and colleagues recently reported that IG-DMR is essential to maintain fetal liver HSCs21. Qian et al. performed an in-depth study using a global constitutive KO approach to show that the long-term repopulating capacity of fetal liver HSCs is impaired upon loss of imprinting of the Dlk1-Meg3 locus. Fetal liver HSCs and adult HSCs greatly differ in their cellular properties such as cycling22–24. Thus, due to the specific expression of Meg3 in adult HSCs, we aimed to address the role of Meg3 in adult mouse hematopoiesis. Since constitutive Meg3-Dlk1 knockout mouse models are embryonically lethal, we employed a floxed Meg3 mouse model created by Klibanski and colleagues (Klibanski et al. unpublished) to generate inducible HSC Meg3 knockout mice. Here, we provide genetic evidence that Meg3 in adult HSCs is dispensable for adult hematopoiesis not only during homeostasis and recovery from inflammatory conditions, but also for reconstitution upon HSC transplantation.

Results

Loss of Meg3 expression does not impair adult hematopoiesis

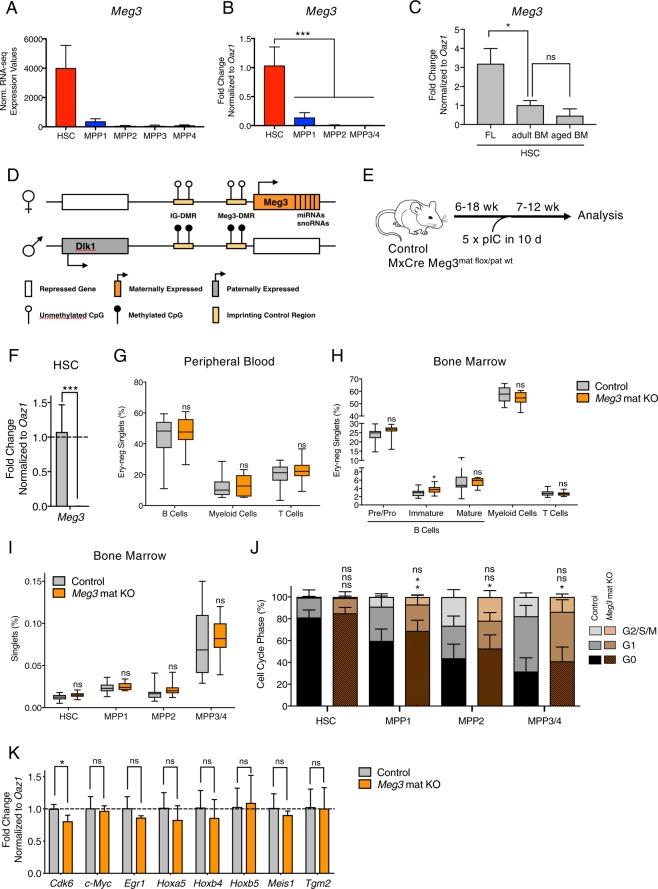

RNA-seq analysis of adult HSC and MPP populations revealed the lncRNA Meg3 to be highly and specifically expressed in HSCs when compared to progenitors (Fig. 1A)8. We confirmed these observations by qPCR analysis (Fig. 1B). Meg3 expression is high in HSCs independent of age and decreases from the fetal liver towards the aged bone marrow (BM) stage (Fig. 1C). To investigate the functional role of Meg3 in adult HSCs, we used an inducible transgenic mouse model in which exon 1 to 4 of the Meg3 allele are floxed (Meg3mat-flox/pat-flox, Fig. 1D). We crossed female Meg3mat-flox/pat-flox mice to male MxCre driver mice to generate MxCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice (from now on Meg3 mat KO)25. The Meg3 locus is imprinted and Meg3 is only expressed from the maternally inherited allele harboring unmethylated DMRs (Fig. 1D). To delete Meg3 in the hematopoietic compartment, we injected adult mice with Poly(I:C) (pIC) to induce Cre expression (Fig. 1E). We kept KO mice for a minimum of 7 weeks prior to analysis to allow recovery of the hematopoietic system to a homeostatic state. After this recovery phase, we sacrificed mice and analyzed primary and secondary hematopoietic organs. First, we confirmed KO efficiency by sorting HSCs (Lineage- Sca1+ Kit+ (LSK) CD150+ CD48− CD34−) and performing qPCR analysis (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Fig. 1A). Deletion of the maternal allele was sufficient to completely disrupt Meg3 expression. In addition, we analyzed differentially expressed miRNAs by “small RNA-Seq” from LSK CD150+ CD48− cells (Supplementary Fig. 1B). We detected 12 mature miRNAs to be differentially expressed between KO and control cells. Ten of these miRNAs belong to the Dlk1-Meg3 locus and were all found to be strongly downregulated in Meg3 KO cells. However, we observed no differences in lineage composition in the peripheral blood as determined by flow cytometry analysis. The numbers of B cells, T cells as well as myeloid cells were not affected by loss of Meg3 expression (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Fig. 1C). Next, we analyzed total blood counts of white blood cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes and observed no significant differences (data not shown). Subsequently, we analyzed the BM composition and in line with peripheral values, we observed no differences in mature cells (myeloid, B, T cells) between control and Meg3 mat KO mice (Fig. 1H, Supplementary Fig. 1D). Similarly, we did not detect any signs of impairment in spleen and thymus upon Meg3 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 1E,F). Next, we analyzed the effects of Meg3 deletion on the HSC/MPP compartment. Our analyses did not reveal any differences in HSC and MPP frequencies (Fig. 1I, Supplementary Fig. 1G). We observed a minor increase in G0 of MPPs in cell cycle analysis, however no differences were observed in HSCs (Fig. 1J, Supplementary Fig. 1H). To analyze the molecular profile of Meg3 mat KO HSCs, we performed qPCR analysis of HSC-specific and -regulatory genes in control and KO cells (Fig. 1K). Genes were selected based on gene expression signatures identified in previous publications8,9. Except for slightly reduced Cdk6 levels in Meg3 mat KO HSCs, we did not observe any deregulation of HSC-specific genes upon loss of Meg3 expression. Collectively, our data show no apparent impairment of adult hematopoiesis in Meg3 mat KO mice despite the high and specific expression of the lncRNA Meg3 in adult HSCs.

Figure 1.

Meg3 is highly and specifically expressed in HSCs, however Meg3 mat KO mice exhibit normal hematopoiesis. (A,B) Meg3 expression was analyzed by RNA-seq (data derived from8) (A, n = 3–4, mean + SD) or qPCR analysis (B, n = 3, mean + SD, one-way ANOVA) in sorted homeostatic HSCs (LSK CD48− CD150+ CD34− (CD135−)), MPP1 (LSK CD48− CD150+ CD34+ (CD135−)), MPP2 (LSK CD48+ CD150+ (CD135−)), MPP3 (LSK CD48+ CD150− (CD135−)), MPP4 (LSK CD48+ CD150− (CD135+)) or MPP3/4 (LSK CD48+ CD150−) cells. For details on employed surface marker combinations see Supplementary Fig. 1A and Material and Methods (C) Meg3 expression in fetal liver (FL) E13.5, adult bone marrow (BM) and aged BM HSCs analyzed by qPCR. n = 3, mean + SD, student’s t-test. For details on employed surface marker combinations see Supplementary Fig. 1A and Material and Methods (D) Schematic Representation of the Dlk1-Meg3 locus (Modified after38). (E) Workflow of Cre induction by pIC and consecutive analysis. (F) qPCR analysis of Meg3 in sorted control and Meg3 mat KO HSCs. n = 7, mean + SD, unpaired student’s t-test. (G,H) Flow cytometry-based analysis of differentiated PB (G) and BM cells (H). Percent of erythrocyte negative cells is depicted. n = 12–18, unpaired student’s t-test. (I) HSC, MPP1, MPP2, and MPP3/4 frequencies determined by flow cytometry analysis. Percentage of BM HSC/MPPs are represented. n = 11–16, unpaired student’s t-test. (J) Cell cycle analysis of HSCs/MPPs. Relative percentage within each cell-cycle phase is shown. n = 9–15, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. (K) qPCR analysis of HSC signature genes in sorted control and Meg3 mat KO HSCs. n = 3, mean + SD, unpaired student’s t-test. For all experiments: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. n indicates number of biological replicates; all panels: 3 independent experiments.

Meg3 expression is dispensable for HSC engraftment and long-term function in serial BM transplantation experiments

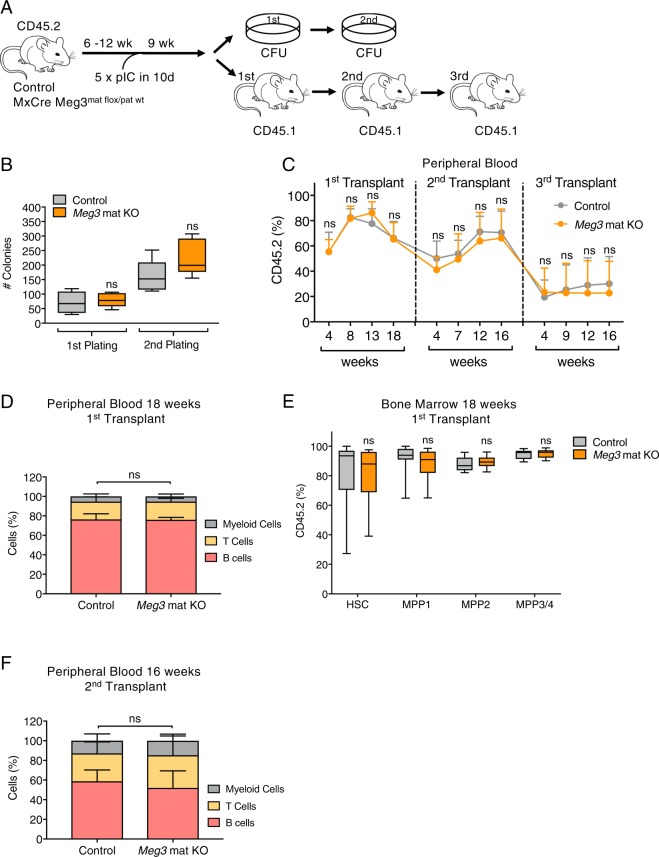

Analysis of steady-state hematopoiesis 7 to 12 weeks after MxCre mediated Meg3 deletion may not necessarily reveal functional HSC impairment as contribution of HSCs to mature cell output during homeostasis is small26,27. To functionally evaluate the effects of Meg3 loss in HSCs, we performed in vitro colony forming unit (CFU) assays and in vivo serial transplantation assays (Fig. 2A). We did not detect functional defects in adult Meg3 mat KO HSC/MPPs in serial CFU assays (Fig. 2B). In addition, we analyzed engraftment and lineage output in full chimeras and did not observe differences upon Meg3 mat KO (Fig. 2C–F). Overall, we detected comparable engraftment of BM cells (CD45.2) in primary lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1) 4 weeks after transplantation between KO and control cells (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. 2A). Contribution of transplanted cells to the peripheral blood was not altered by Meg3 mat KO over time in primary recipients. We performed endpoint analysis after 18 weeks and observed no lineage bias of the transplanted cells in the peripheral blood (Fig. 2D). In addition, we conducted analysis of the BM and detected comparable engraftment of Meg3 mat KO and control HSCs and MPPs (Fig. 2E). To ensure that Meg3 mat KO was maintained in HSCs and no escapees grew out, we performed qPCR analysis of sorted CD45.2+ HSCs from 18-week primary recipients (Supplementary Fig. 2B). We did not detect Meg3 expression in KO HSCs, confirming stable KO and contribution of KO cells to lineage output. Furthermore, we did not observe differences in the differentiated lineages in the BM and the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Reconstitution of full chimeras and lineage output is not impaired in Meg3 mat KO mice. (A) Workflow depicting Cre induction and functional analysis by colony forming unit (CFU) assays and generation of full chimeras. (B) Functional analysis by serial CFU assays. n = 5–6, unpaired student’s t-test. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of serial transplantation experiments. CD45.2% outcome is shown. n = 9, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. (D) Lineage output in PB of primary recipients 18 weeks after transplantation as determined by flow cytometry analysis in CD45.2+ cells. n = 9, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of HSC/MPP cells in BM of primary recipients 18 weeks after transplantation. CD45.2% outcome is shown. n = 9, unpaired student’s t-test. (F) Lineage output in PB of secondary recipients 16 weeks after transplantation as determined by flow cytometry analysis in CD45.2+ cells. n = 9, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. For all experiments: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. n indicates number of biological replicates; B: 2 independent experiments; C-F: 1 independent experiment.

To investigate long-term engraftment potential, we performed serial transplantation assays. Re-transplantation of total BM cells into secondary recipients did not show impaired engraftment and contribution capacity of Meg3 mat KO HSCs (Fig. 2C). Analysis of secondary recipients 16 weeks after transplantation revealed no differences in lineage output in the peripheral blood (Fig. 2F). Finally, we performed tertiary transplantation assays and again failed to detect differences between control and KO settings (Fig. 2C). No differences in peripheral blood contribution and generation of B cells, T cells or myeloid cells were detected in serial BM transplantation assays (Supplementary Fig. 2E–G). Overall, we conclude that long-term engraftment and functional potential of adult Meg3 mat KO HSCs is not impaired indicating that Meg3 is dispensable for adult hematopoiesis.

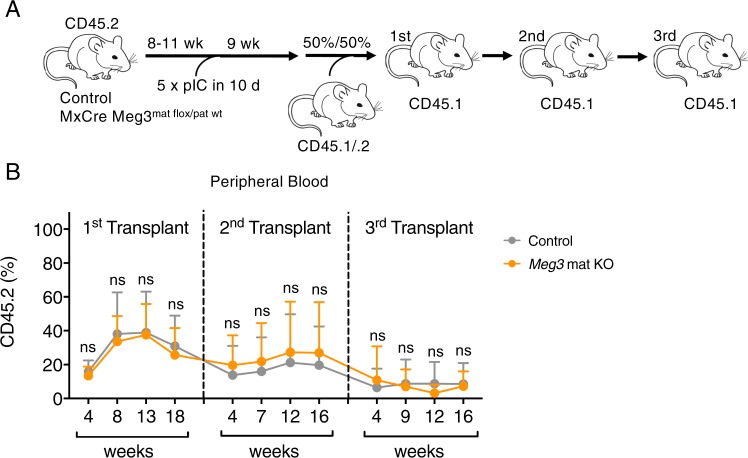

Loss of Meg3 expression does not impair the competitive potential of HSCs

To ensure that Meg3 mat KO HSCs hold equal functional capacities as wildtype HSCs, we set up 50/50 competitive transplantation experiments. 9 weeks after Meg3 deletion in donor mice, we mixed total BM cells of CD45.2 Meg3 mat KO or control mice with CD45.1/2 total BM cells and transplanted them into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice (Fig. 3A). 4 weeks after transplantation, we did not detect competitive disadvantages in transplanted Meg3 mat KO cells compared to control cells (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

No functional impairment of Meg3 mat KO BM is detected in serial competitive repopulation experiments. (A) Workflow depicting Cre induction and functional analysis by serial competitive transplantation experiments. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of serial transplantation experiments. CD45.2% outcome is shown. n = 7–9, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. n(primary) = 9, n(secondary) = 9, n(tertiary) = 7–9, unpaired student’s t-test. For all experiments: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. n indicates number of biological replicates; 1 independent experiment.

As for full chimeras, we performed serial transplantation assays by re-transplanting total BM cells into secondary and tertiary recipients, respectively. We did not observe any competitive disadvantages in peripheral blood contribution over time (Fig. 3B). In addition, no differences in peripheral blood contribution and generation of B cells, T cells or myeloid cells were detected (Supplementary Fig. 3B–D). These findings show that even in competitive transplantation settings, HSCs lacking Meg3 expression do no exhibit functional impairments or deficiencies.

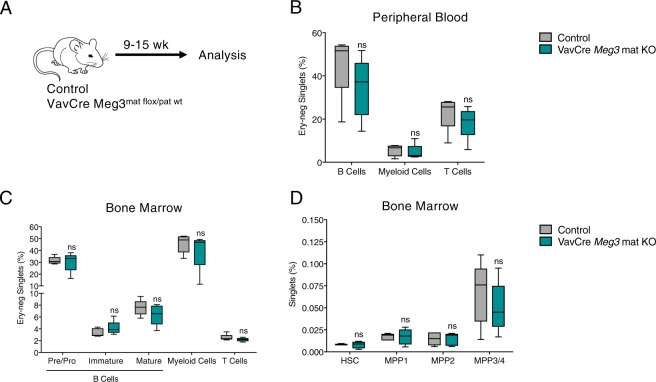

The lncRNA Meg3 is dispensable in HSCs expressing Vav1

Constitutive loss of imprinting of the Dlk1-Meg3 locus leads to impairments in fetal liver HSCs21. To understand the role of Meg3 in definitive HSCs during embryogenesis we generated VavCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice. VavCre mediated deletion has been detected in embryonic stage 11.5 CD45+ aorta–gonad–mesonephro (AGM) and CD45+ fetal liver cells28. Thus, Meg3 is deleted in all cells expressing Vav1, leading to deletion of Meg3 after the endothelial-cell-to-HSC transition during embryogenesis. VavCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice were born and appeared healthy (data not shown). In depth analysis of the hematopoietic system was performed 9–15 weeks after birth (Fig. 4A). Analysis of differentiated cells in the peripheral blood and in the bone marrow did not reveal any alterations in adult mice upon loss of Meg3 in HSCs during embryonic development (Fig. 4B,C). In addition, we analyzed the HSC/MPP compartment and did not observe any changes compared to control mice (Fig. 4D). Complete loss of Meg3 expression was confirmed in adult HSCs by qPCR analysis (data not shown). In summary, Meg3 is not only dispensable in adult HSCs but hematopoiesis is also not impaired upon loss of Meg3 expression in Vav1-expressing hematopoietic cells during embryogenesis.

Figure 4.

VavCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice are viable and exhibit normal hematopoiesis. (A) Workflow. (B,C) Flow cytometry-based analysis of differentiated PB (B) and BM cells (C). Percent of erythrocyte negative cells are depicted. n = 5, unpaired student’s t-test. (D) HSCs, MPP1, MPP2, and MPP3/4 frequencies determined by flow cytometry analysis. Percentage of BM HSC/MPPs are represented. n = 5, unpaired student’s t-test. For all experiments: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. n indicates number of biological replicates; B-D: 2 independent experiments.

Interferon-mediated HSC stress response is marginally affected by lack of Meg3 expression

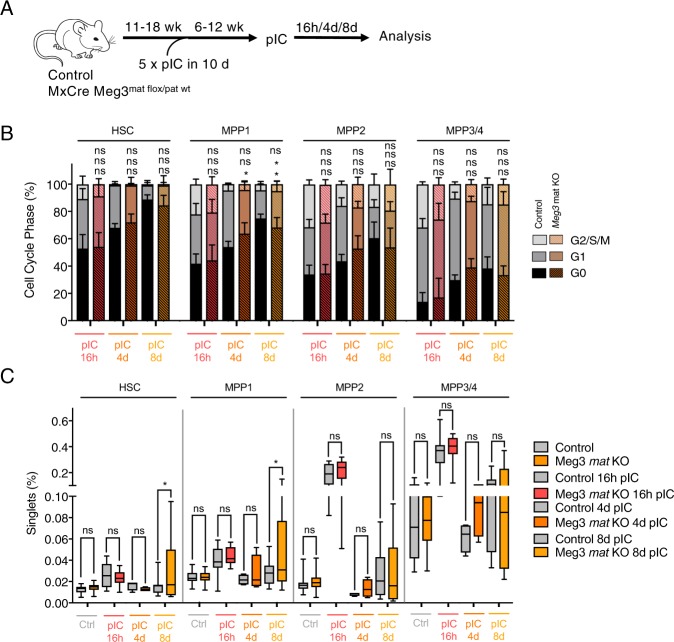

As Meg3 is known to be involved in cell cycle control, we asked whether Meg3 deficiency could impair HSC activation or return to quiescence in response to inflammatory stress conditions. To investigate the interferon-mediated response in HSCs, we performed additional pIC injections 6 to 12 weeks following Meg3 deletion (Fig. 5A). pIC is a dsRNA-analogue and induces a type I interferon (IFNα/β) response, which strongly induces proliferation in the HSC/MPP compartment, including exit from G05. Cells become activated within 16 h after injection and return to quiescence within 8 days. We analyzed the effects of pIC treatment 16 h, 4 days and 8 days after injection to monitor the stress response (Fig. 5A). As expected, HSCs and MPP cells exit G0 16 h after pIC injection (Fig. 5B). This proliferative response was not impaired in any of the analyzed HSC/MPP subsets upon loss of Meg3 expression. From 4 to 8 days we observed a stepwise return to the respective cell cycle status of HSCs and MPPs. We did not see any significant differences between control and Meg3 mat KO HSCs, MPP2 and MPP3/4 cells in the return to a quiescent state. MPP1 cells lacking Meg3, however, showed a slightly increased percentage of cells in G0 after 4 days and a slightly decreased percentage of cells in G0 after 8 days compared to the respective control, indicating a marginally decreased return of mutant cells to quiescence.

Figure 5.

HSC stress response is only marginally affected in Meg3 mat KO HSCs. (A) Workflow depicting pIC-mediated Cre and interferon-mediated stress induction. (B) Flow cytometry-based cell cycle analysis of HSCs/MPPs. Relative percentage within each cell-cycle phase is shown. n = 4–11, mean + SD, two-way ANOVA. (C) HSCs, MPP1, MPP2, and MPP3/4 frequencies determined by flow cytometry analysis. Percentage of BM HSC-MPPs are represented. n = 4–18, one-way ANOVA. For all experiments: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. n indicates number of biological replicates; B-C: 1–4 independent experiments.

In addition to the cell cycle state, we monitored the frequency of the HSC/MPP compartments in the BM (Fig. 5C). As expected, we detected an increase in the respective compartments 16 h after pIC injection that can be explained by the proliferative response5. Over time (4–8 days), the frequency of the respective HSC/MPP compartment was reduced again. This response was not impaired in Meg3 mat KO HSCs and MPPs. Only in HSC and MPP1 cells we observed slightly increased frequencies 8 days after pIC injection in Meg3 mat KO animals. To address whether this slight increase was of biological relevance, we performed serial colony forming unit assays 16 h and 8 days after pIC injection (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We did not observe any significant differences in colony forming capacity in serial plating between control and Meg3 mat KO cells, even though we observed a slight increase in HSC frequency upon Meg3 mat KO during recovery from stress response (Fig. 5C). We conclude, that the slight increase in the HSC compartment during stress recovery is not of major biological relevance for the hematopoietic system. To further strengthen our observations, we performed serial stress experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Ten weeks after Meg3 deletion, mice were injected with pIC for 4 weeks. After an 8-week recovery phase, mice were sacrificed and analyzed. As expected, serial stress led to a reduction in HSC/MPP frequencies. This effect was not altered in Meg3 mat KO cells. Overall, this indicates that Meg3 is not required for the proliferative response and recovery upon interferon-mediated inflammatory stress.

Discussion

Meg3 is known to play an important functional role in embryonic development as shown in several mouse genetic studies17–19. The severity of the observed developmental phenotypes depends on the applied genetic targeting strategy. For example, IG-DMR KO and Meg3 KO models were recently used to investigate the effects of Dlk1-Meg3 imprinting loss on fetal liver HSCs17,18,21. Using these models, Qian et al. observed reduced fetal liver HSC frequency and showed their functional impairment by transplantation into adult mice. Interestingly, expression patterns of the Dlk1-Meg3 locus in fetal liver and adult HSCs seem to be highly conserved21. Here we employed an inducible MxCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mouse model to induce deletion of Meg3 in mice after the establishment of adult homeostatic hematopoiesis. Thereby, we were able to directly investigate the consequences of loss of Meg3 expression on adult hematopoiesis, excluding potential developmental and microenvironmental impairments that could eventually affect HSCs. Since adult HSCs are deeply quiescent/dormant and Meg3 is known to be involved in cell cycle regulation via the p53- and Rb-pathways, we used straight and competitive transplantation assays to challenge HSCs and to further investigate HSC function over time22,29–31. We performed extensive analyses and observed no biologically relevant differences in homeostatic and stressed hematopoiesis upon loss of Meg3 expression. To address the role of Meg3 during embryonic development, we deleted Meg3 in CD45+ cells in the murine embryo by using Vav1 as a Cre driver. Surprisingly, mice were viable and no signs of hematopoietic impairments were observed in adult mice. Therefore, Meg3 seems to be dispensable for embryonic establishment of hematopoiesis and Meg3 does not seem to be important for HSC function after the endothelial-cell-to-HSC transition28. However, Meg3 might be important for this transition step during development leading to the defects in fetal liver HSCs observed by Qian et al.21. Importantly, our model is targeting exon 1–4 of the Meg3 locus, leading to loss of Meg3 expression and loss of expression of the miRNA cluster, and does not target DMRs. A broader disruption of the imprinted locus could potentially lead to globally altered expression patterns, which in turn could affect hematopoiesis – independent of Meg3 and the miRNA cluster itself. Future studies will need to shed light on the effects of DMR targeting affecting the entire Meg3-Dlk1 locus in adult hematopoiesis. Meg3 is additionally known to act as a tumor suppressor in several types of cancer including leukemia14,15,32. Meg3 has been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo and acts via a p53-dependent and -independent axis in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines15,32. In our study, we show that loss of Meg3 alone did not lead to the development of leukemia or myeloproliferative diseases even in long-term experiments such as tertiary transplantations. Furthermore, no proliferative advantages of Meg3 mat KO cells were observed. Thus, based on these observations the loss of the tumor suppressor Meg3 alone is not sufficient for cell transformation in the hematopoietic system. In line with our results, loss of Meg3 mostly occurs upon epigenetic silencing supporting the concept that Meg3 dysregulation might result as a secondary event during the development of leukemia15. Future studies will be necessary to better understand the role of Meg3 in development and maintenance of leukemia.

Methods

Mice

Meg3 flox mice were generated by Klibanski et al., loxP sites flank exon 1 to 4 (Klibanski, unpublished). Female Meg3 flox mice were crossed to male MxCre driver mice25, generating MxCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice. Cre+ animals were used in experiments. As control mice, MxCre mice or Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice were used. All animals were injected 5 times over 10 days intraperitoneally with pIC (100 µg pIC in PBS) 6–18 weeks after birth. Analysis or further experiments were started 6–12 weeks after deletion. Female Meg3 flox mice were crossed to male VavCre driver mice33 for analysis of embryonic Meg3 deletion, generating VavCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice. Mice were analyzed 9–15 weeks after birth. As control mice, Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt littermates were used. C57BL/6 J mice, 11–17 weeks old (CD45.2, CD45.1 or CD45.2/CD45.1) were either purchased from Harlan Laboratories (now Envigo) (the Netherlands) or Janvier Labs (France) or bred in-house. Euthanization of mice by cervical dislocation and all animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the German authorities, Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe (Nr. A23/17, Z110/02, DKFZ 299 and G149-16). Generation of “small RNA-Seq data” was performed using residual material from Meg3 KO and control mice generated during the reported experiments under the test number G149-16

Cell Suspension and Flow Cytometry

Peripheral Blood and BM Analysis

For isolation of BM, spleen and thymus cells, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Femur, tibia, hip and spine bones, spleen and thymus were isolated. Bones were crushed in ice-cold PBS using pistil and mortar. The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 40 µM cell strainer and pelleted by centrifugation. Total BM cells were used for colony forming unit or transplantation assays. For flow cytometry analysis and FACS, erythrocytes were lysed using ACK Lysing Buffer (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). BM cells were counted using a Vi-CellXR Cell Viability Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and used for flow cytometry stainings.

FACS

For FACS, total BM cells were lineage depleted by using the Dynabeads Untouched Mouse CD4 Cells Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, total BM was stained with a 1:5 dilution of the Lineage Cocktail provided in the Kit for 30 min. Cells were incubated for 20 min with 1.5 mL beads per mouse of washed Dynabeads. A magnet was used for cell depletion to enrich for the lineage-negative cell fraction. To purify HSCs, the depleted cells were stained for 30 min using the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-lineage [anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti- B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-GR1 (RB6-8C5) and anti-TER119 (Ter-119)] all PE-Cy7; anti-CD117/c-Kit (2B8)-PE; anti-Ly6a/Sca-1 (D7)-APC-Cy7; anti-CD34 (RAM34)-FITC; anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2)-PE-Cy5; anti-CD48 (HM48-1)-PB. For isolation of transplanted HSCs, the following monoclonal antibodies were used: anti-lineage [anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti- B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-GR1 (RB6-8C5) and anti-TER119 (Ter-119)] all AF700; anti-CD117/c-Kit (2B8)-APC; anti-Ly6a/Sca-1 (D7)-APC-Cy7; anti-CD34 (RAM34)-FITC; anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2)-PE-Cy5; anti-CD48 (HM48-1)-PE; anti-CD45.1 (A28)-PE-Cy7; anti-CD45.2 (104)-PB. Monoclonal antibody conjugates were purchased from eBioscience (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) or BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Cell sorting was performed on a FACS Aria II (Becton Dickinson). Sorted cells were collected into RNA lysis buffer (ARCTURUS PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)) for qPCR analysis and stored at −80 °C.

Flow Cytometry

Ery-lysed peripheral blood and BM cells were used for flow cytometry stainings. Supplementary Table 1 defines the monoclonal antibodies applied for the different surface staining approaches. Cells were stained for 30 min at 4 °C. For cell cycle stainings, surface stainings were performed and cells were fixed and permeabilized by using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Buffer (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Subsequently, intracellular Ki-67 (B56)-AF647 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) staining was performed in PermWash solution (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Then cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 15 min at RT. Monoclonal antibody conjugates were purchased from eBioscience (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) or BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA).

Gene Expression Analysis by qPCR

HSCs (MxCre or MxCre Meg3mat flox/pat wt LSK CD150+ CD48− CD34− or fetal liver HSCs: embryonic stage 13.5 CD48− CD41+ cKit+ CD34+; adult HSCs (8–12 weeks): LSK CD150+ CD48− CD34− CD135−; aged HSCs (24 month): LSK CD150+ CD48− CD34− CD135−) were FACS sorted into RNA lysis buffer (ARCTURUS PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)) for qPCR analysis and stored at −80 °C. RNA was isolated using the ARCTURUS PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. For cDNA synthesis, reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used on a ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for qPCR analysis. RNA expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene Oaz1 and presented as relative quantification (Ratio = 2−DDCT). For Primer Sequences see Supplementary Table 2.

Small RNA Sequencing

Sample Preparation and Library Generation

Approximately 10,000–20,000 LSK SLAM cells (LSK CD150+ CD48−) were FACS sorted into 100 µl QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Total RNA Extraction was performed by adding 20 µl Chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Samples were incubated at RT and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 5 min at RT. The aqueous phase was taken and 0.4 µl glycoblue (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and 75 µl Isopropanol were added per sample. Samples were stored at −20 °C for at least 5 days. Samples were centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were washed with 70% Ethanol and centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was discarded and the pellet was dried for 1 min. The Pellet was resuspended in 8 µl H2O. RNA quality was analyzed using the Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries for small RNA-Seq were generated using the SMARTer® smRNA-Seq Kit for Illumina® (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga Prefecture, Japan) according to manufacturer’s instructions. 23 ng of total RNA were used and 15 cycles were applied for PCR amplification. Quality was checked using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Size selection was performed by using AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on a HiSeq 2000 device (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

MiRNA Sequencing Analysis

Genomic Mapping

The adapter sequences ATGATCGGAAGAG, GATGAAGAACGCAG, AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGTAGGGAAAGAGTGT, GGTCTACG, TGGAATTCTCGGGTGCCAAGG, TCGTATGCCGTCTTCTGCTTG, AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCA were removed with Trimmomatic34 (version 0.32, parameters: SE ILLUMINACLIP:adapter:2:30:10 HEADCROP:4 TRAILING:3 MINLEN:17) from the fastq sequences, additionally all reads containing N and all sequences <17 bases were removed. HomerTools35 (v3.18, trim -3 AAAAAAAAA) for removing polyA tails and fastx_artifacts_filter (FASTX Toolkit 0.0.13 http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) were used for further cleaning. Then the clean fastq files were mapped against mouse genome 38 (NCBI) using Bowtie 2 version 2.2.436 (parameters -N 0 -L 8). The resulting SAM files were converted to BAM and sorted using samtools version 1.3.1.

miRNA Mapping and Counting

The clean fastq files were mapped with bowtie version 0.12.9 (-f -v 1 -a–best -S) against an assembled ncRNA database consisting of a unique set of miRNAs of Ensembl version 95 (http://www.ensembl.org/) and miRBase (v21, http://www.mirbase.org/). The resulting SAM files were parsed and the number of reads for each mature miRNA was counted using Perl.

Comparison of Control Cre and KO samples

For the comparison with DESeq. 237 the input tables containing the replicates for the groups to compare were created by a custom perl script. In the count matrix rows with an average count number <5 were removed, then DESeq. 2 (version 1.4.1) was run with default parameters.

Transplantation Experiments

Full Chimeras

1 × 106 total BM cells from induced MxCre control mice or induced MxCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 mice within 24 h after irradiation by tail vein injection. 18 weeks after transplantation, mice were euthanized and 3 × 106 total BM cells were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 secondary recipient mice. 16 weeks after transplantation, mice were euthanized and 3 × 106 total BM cells were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 tertiary recipient mice. Contribution of CD45.2-donor cells was monitored in peripheral blood approximately every 4 weeks by flow cytometry using the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD45.1 (A20)-PECy7, anti-CD45.2 (104)-PB, anti-CD11b (M1/70)-AF700, anti-GR1 (RB6.8C5)-APC, anti-CD8a (53.6.7)-PE, anti-CD4 (GK1.5)-PE, anti-B220 (RA3.6B2)-PE-Cy5.

50/50 Chimeras

2 × 105 total BM cells from induced MxCre control mice or induced MxCre Meg3mat-flox/pat-wt mice were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 mice within 24 h after irradiation by tail vein injection in competition to 2 × 105 total BM cells from CD45.1/2 mice. 18 weeks after transplantation, mice were euthanized and 3 × 106 total BM cells were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 secondary recipient mice. 16 weeks after transplantation, mice were euthanized and 3 × 106 total BM cells were transplanted into fully irradiated (2 × 5 Gy.) CD45.1 tertiary recipient mice. Contribution of CD45.2-donor cells was monitored in peripheral blood approximately every 4 weeks by flow cytometry using the following monoclonal antibodies: anti-CD45.1 (A20)-PECy7, anti-CD45.2 (104)-PB, anti-CD11b (M1/70)-AF700, anti-GR1 (RB6.8C5)-APC, anti-CD8a (53.6.7)-PE, anti-CD4 (GK1.5)-PE, anti-B220 (RA3.6B2)-PE-Cy5.

pIC Stress Experiments

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 µg pIC (in PBS) or PBS either 8 days, 4 days or 16 h prior to endpoint analysis. For serial stress experiments, mice were injected for a period of 4 weeks 2 times a week. Mice were analyzed 8 weeks after the last pIC injection.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired Student’s t test or two- or one-way ANOVA without correction for multiple comparison (Fisher LSD test). Significance levels were set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all technicians of the Trumpp laboratory for technical assistance; P. Werner and F. Pilz of Marieke Esser’s laboratory for generously providing cDNA samples of fetal liver HSCs; L. Becker of the Trumpp laboratory for assistance with QIAzol-Chloroform RNA extraction; S. Schmitt, M. Eich, K. Hexel, T. Rubner from the DKFZ Flow Cytometry Core Facility for their assistance; K. Reifenberg, P. Prückl, M. Schorpp-Kistner, A. Rathgeb and all members of the DKFZ Laboratory Animal Core Facility for excellent animal welfare and husbandry. We thank Dr. M.A. Goodell for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the FOR2033 and the SFB873 funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), the SyTASC consortium funded by the Deutsche Krebshilfe and the Dietmar Hopp Foundation (all to A.T).

Author Contributions

P.S., S.R., L.L., K.S., P.Z., A.P., M.S. and Y.Z. performed experiments; P.S. and A.H.-W. analyzed results and P.S. made the figures; P.S., A.K., N.C.-W. and A.T. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Data Availability

The small RNA-Seq dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available in the ArrayExpress repository, ArrayExpress accession E-MTAB-7519 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nina Cabezas-Wallscheid and Andreas Trumpp jointly supervised this work.

Contributor Information

Nina Cabezas-Wallscheid, Email: cabezas@ie-freiburg.mpg.de.

Andreas Trumpp, Email: a.trumpp@dkfz.de.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-38605-8.

References

- 1.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter D, et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2015;520:549–552. doi: 10.1038/nature14131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature09135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Essers MA, et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature07815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Till JE, Mc CE. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat Res. 1961;14:213–222. doi: 10.2307/3570892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazit R, et al. Transcriptome analysis identifies regulators of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, et al. Identification of regulatory networks in HSCs and their immediate progeny via integrated proteome, transcriptome, and DNA methylome analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, et al. Vitamin A-Retinoic Acid Signaling Regulates Hematopoietic Stem. Cell Dormancy. Cell. 2017;169:807–823 e819. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo M, et al. Long non-coding RNAs control hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yildirim E, et al. Xist RNA is a potent suppressor of hematologic cancer in mice. Cell. 2013;152:727–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez-Dominguez JR, Lodish HF. Emerging mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function during normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Blood. 2017;130:1965–1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-788695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klimmeck D, et al. Transcriptome-wide profiling and posttranscriptional analysis of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell differentiation toward myeloid commitment. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:858–875. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benetatos L, Vartholomatos G, Hatzimichael E. MEG3 imprinted gene contribution in tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:773–779. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Klibanski A. MEG3 noncoding RNA: a tumor suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48:R45–53. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.da Rocha ST, Edwards CA, Ito M, Ogata T, Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting at the mammalian Dlk1-Dio3 domain. Trends Genet. 2008;24:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SP, et al. Asymmetric regulation of imprinting on the maternal and paternal chromosomes at the Dlk1-Gtl2 imprinted cluster on mouse chromosome 12. Nat Genet. 2003;35:97–102. doi: 10.1038/ng1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi N, et al. Deletion of Gtl2, imprinted non-coding RNA, with its differentially methylated region induces lethal parent-origin-dependent defects in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1879–1888. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, et al. Activation of paternally expressed genes and perinatal death caused by deletion of the Gtl2 gene. Development. 2010;137:2643–2652. doi: 10.1242/dev.045724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg JS, et al. Imprinted genes that regulate early mammalian growth are coexpressed in somatic stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian P, et al. The Dlk1-Gtl2 Locus Preserves LT-HSC Function by Inhibiting the PI3K-mTOR Pathway to Restrict Mitochondrial Metabolism. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nygren JM, Bryder D, Jacobsen SE. Prolonged cell cycle transit is a defining and developmentally conserved hemopoietic stem cell property. J Immunol. 2006;177:201–208. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowie MB, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells proliferate until after birth and show a reversible phase-specific engraftment defect. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2808–2816. doi: 10.1172/JCI28310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun J, et al. Clonal dynamics of native haematopoiesis. Nature. 2014;514:322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature13824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busch K, et al. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2015;518:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature14242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457:887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, et al. Activation of p53 by MEG3 non-coding RNA. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24731–24742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Zhou Y, Klibanski A. Isolation and characterization of novel pituitary tumor related genes: a cDNA representational difference approach. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;326:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passegue E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC, Weissman IL. Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1599–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyu Y, et al. Dysfunction of the WT1-MEG3 signaling promotes AML leukemogenesis via p53-dependent and -independent pathways. Leukemia. 2017;31:2543–2551. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georgiades P, et al. VavCre transgenic mice: a tool for mutagenesis in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages. Genesis. 2002;34:251–256. doi: 10.1002/gene.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kameswaran V, Kaestner KH. The Missing lnc(RNA) between the pancreatic beta-cell and diabetes. Front Genet. 2014;5:200. doi: 10.3389/fgene.201400200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The small RNA-Seq dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available in the ArrayExpress repository, ArrayExpress accession E-MTAB-7519 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/).