Abstract

Plant cytokinesis involves membrane trafficking and cytoskeletal rearrangements. Here, we report that the phosphoinositide kinases PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 integrate these processes in Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) roots. Cytokinetic defects of an Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant are accompanied by defects in membrane trafficking. Specifically, we show that trafficking of the proteins KNOLLE and PIN2 at the cell plate, clathrin recruitment, and endocytosis is impaired in pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants, accompanied by unfused vesicles at the nascent cell plate and around cell wall stubs. Interestingly, pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 plants also display ectopic overstabilization of phragmoplast microtubules, which guide membrane trafficking at the cell plate. The overstabilization of phragmoplasts in the double mutant coincides with mislocalization of the microtubule‐associated protein 65‐3 (MAP65‐3), which cross‐links microtubules and is a downstream target for inhibition by the MAP kinase MPK4. Based on similar cytokinetic defects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 and mpk4‐2 mutants and genetic and physical interaction of PI4Kβ1 and MPK4, we propose that PI4Kβ and MPK4 influence localization and activity of MAP65‐3, respectively, acting synergistically to control phragmoplast dynamics.

Keywords: Cell division; cell plate; clathrin‐mediated endocytosis, phosphoinositides; mitogen‐activated protein kinase 4

Subject Categories: Membrane & Intracellular Transport, Plant Biology

Introduction

Cytokinesis is the final step of cell division to separate a mother cell into two daughter cells, and of fundamental importance both in animals and in plants. In animals, cytokinesis is characterized by the formation of the cleavage furrow and contractile ring (Glotzer, 2001). The cleavage furrow is a membrane barrier dividing the cytoplasm of the mother cell onto the daughter cells, whereas the contractile ring, consisting of actin and myosin, pulls the cleavage furrow inward to isolate the daughter cells. In contrast, cytokinesis in plant cells adopts a specialized strategy because of the presence of plant cell walls and involves the formation of the cell plate as a plant‐specific membrane compartment for cell division (Jürgens, 2005; McMichael & Bednarek, 2013). In late anaphase/early telophase, the cell plate initiates between a mirrored array of microtubules, the phragmoplast, which provides guidance to membrane trafficking events delivering vesicles to the cell plate (Smertenko et al, 2017a,b). After its insertion in the cortical division site, the cell plate will mature and incorporate new plasma membrane and cell wall. During this process, the phragmoplast expands radially outward around the growing cell plate, transiting from a solid to a ring‐like structure. This process requires tight spatio‐temporal coordination of cytoskeleton and membrane trafficking (Smertenko et al, 2017b). Although details of their cell division machineries differ, cytoskeleton rearrangement and membrane trafficking are necessary and critical for successful cytokinesis in both animals and plants (D'Avino et al, 2005; McMichael & Bednarek, 2013).

The lateral expansion of phragmoplasts is regulated via the depolymerization of microtubules in the central part of the phragmoplast and polymerization of tubulins at the periphery (Nishihama & Machida, 2001; Murata et al, 2013). Several regulatory players are known to control phragmoplast expansion in plants. In tobacco bright yellow‐2 (BY‐2) cell cultures, the NPK1‐activating kinesin‐like proteins (NACKs) directly bind to and activate the mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK), nucleus‐ and phragmoplast‐localized protein kinase 1 (NPK1; Nishihama et al, 2002; Sasabe & Machida, 2012). The activated NPK1 triggers phosphorylation of downstream components of the cascade, such as the MAPKK, NQK1 (Soyano et al, 2003), and the MAPK, NRK1 (Soyano et al, 2003), constituting the NACK‐PQR pathway. NRK1 finally phosphorylates the microtubule‐associated protein 65‐1 (NtMAP65‐1), thereby decreasing its capacity to bundle microtubules, facilitating turnover and radial expansion of the phragmoplast (Sasabe et al, 2006). All counterparts for the tobacco pathway have been identified in Arabidopsis, including sequential action of the proteins HINKEL/STUD (homologs of NACK1 and NACK2) activating a MAPK cascade consisting of ANP1‐3 (MAPKKKs), MKK6/ANQ, and finally MPK4, which can phosphorylate the targets MAP65‐1, MAP65‐2, and MAP65‐3 that are supposed to promote phragmoplast expansion (Strompen et al, 2002; Tanaka et al, 2004; Beck et al, 2010; Takahashi et al, 2010; Sasabe et al, 2011). In consequence, loss‐of‐function of MPK4 results in delayed or abortive transition of mitotic and cytokinetic microtubules and causes heavily bundled microtubules, which ultimately affect the pattern of cell division orientation in the mpk4‐2 mutant (Beck et al, 2010, 2011). During cytokinesis, MPK4 and MAP65‐3 are both concentrated at the midline of the phragmoplast. MAP65‐3 is critical for cytokinesis through bundling anti‐parallel microtubules at the midline to establish the phragmoplast microtubule array, while mutation of other members of the MAP65 family does not cause cytokinetic defects (Kosetsu et al, 2010; Ho et al, 2011).The transition of the phragmoplast from a solid to a ring‐like array drives vesicles delivered along phragmoplast microtubules from the center toward the leading edges of the cell plate, resulting in their fusion and leading to the cell plate growing outward (Müller & Jürgens, 2016). Currently, little is known about how membrane trafficking is coordinated in spatio‐temporal concert with the lateral expansion of the phragmoplast.

In all eukaryotes, membrane trafficking is controlled by phosphoinositides, a minor class of regulatory phospholipids that are derived from phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) by phosphorylation of the lipid head group (Munnik & Nielsen, 2011; Gerth et al, 2017). Phosphatidylinositol 4‐phosphate (PtdIns(4)P) is thought to have functions in the regulation of endomembrane trafficking at the trans‐Golgi network (TGN; Vermeer et al, 2009; Simon et al, 2016; Gerth et al, 2017). In plant cells, secretion and endocytosis both converge at the TGN (Viotti et al, 2010) and make contributions to cell plate formation. A key player of cell plate formation is the cytokinesis‐specific syntaxin, KNOLLE, which is by default synthesized only in G2/M phase and endocytosed by clathrin‐mediated endocytosis (CME), restricting its distribution to the cell plate during late cytokinesis (Reichardt et al, 2007; Boutté et al, 2010). As in Arabidopsis PtdIns(4)P resides mainly at the plasma membrane, the TGN, and the cell plate (Vermeer et al, 2009; Simon et al, 2014), we hypothesized that this lipid may serve a function in cytokinesis and cell plate formation. PtdIns(4)P is produced in Arabidopsis by several isoforms of PI4‐kinase (PI4K), including PI4Kα1, PI4Kα2, PI4Kβ1, and PI4Kβ2 (Mueller‐Roeber & Pical, 2002). Even though knockout mutants of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 display a dwarf phenotype (Preuss et al, 2006) accompanied by cytokinesis defects (Kang et al, 2011), and PtdIns(4)P has been known to reside at the cell plate for some years (Vermeer et al, 2009), little is known about how PtdIns(4)P controls cytokinesis in plants, affecting membrane trafficking or cytoskeleton organization, or both.

Here, we show in Arabidopsis root cells that PtdIns(4)P formation affects both membrane trafficking and phragmoplast organization during cytokinesis. PI4Kβ1 furthermore influences the localization of MAP65‐3, resulting in altered dynamics of phragmoplast microtubules and defective cytokinesis. Based on similar cytokinetic defects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 and mpk4 mutants, their genetic interaction, and in vitro physical interaction of PI4Kβ1 and MPK4 proteins, we propose that both PI4Kβ isoforms and MPK4 contribute to the regulation of MAP65‐3 and act synergistically to control phragmoplast dynamics during somatic cytokinesis.

Results

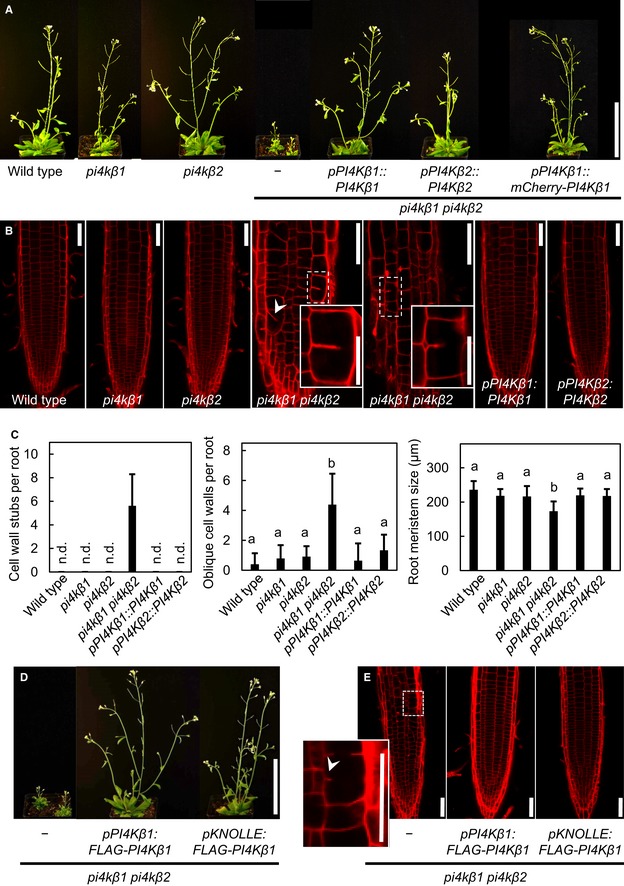

PI4Kβ1 is involved in cytokinesis and localizes to the cell plate

To explore the cytokinesis defects of the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011), we first expressed the coding sequences (CDSs) of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 under their endogenous promoters in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant background. The dwarf phenotype of the double mutant was fully rescued by the ectopic expression of either gene (Fig 1A), indicating that the phenotypes were indeed a result of mutations in PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2. Cytokinetic defects were further analyzed by propidium iodide (PI) staining in the single mutants, the double mutant, and the complemented lines. Cell wall stubs or oblique cell walls reported previously for the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Kang et al, 2011) were not found in the complemented lines (Fig 1B and C), indicating the complementation constructs were functional. The complementation also reverted the incidence of oblique cell walls and the reduced meristem size of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 1C). Further experiments were initiated to determine the subcellular localization of PI4Kβ1 in cytokinetic root cells of Arabidopsis. To our knowledge, no functional fluorescence‐tagged PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 has been reported, so the in vivo localization of PI4Kβ isoforms in Arabidopsis has remained unclear. Therefore, we developed functional complementation constructs, either fusing the CDS of an N‐terminal mCherry tag upstream of an 11‐kb genomic fragment of the PI4Kβ1 gene including introns, 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR, and parts of sequences of the upstream and downstream neighboring genes or fusing an N‐terminal FLAG tag for immunodetection. We focused on PI4Kβ1, as it has 83% identity to PI4Kβ2 and the enzymes are functionally redundant (Preuss et al, 2006). Both the mCherry‐tagged PI4Kβ1 and the FLAG‐tagged PI4Kβ1 complemented the phenotype of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 1A, D and E) and were thus found functional for further analyses. To furthermore test the contribution of PI4Kβ1 to the control of cytokinesis, a functional FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 construct was expressed in pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants under the control of KNOLLE cis‐regulatory elements (pKNOLLE:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1), aiming to confine FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 expression to cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Muller et al, 2003; Fig 1D and E). The pKNOLLE:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 rescued the growth and cytokinetic/cell division orientation defects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 1E and Appendix Fig S1A), but not previously reported root hair defects (Preuss et al, 2006; Appendix Fig S1B), suggesting involvement of PI4Kβs in cytokinesis as well as in other cellular processes. We tried to investigate PI4Kβ1 localization in pKNOLLE:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 lines and pPI4Kβ1:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 lines by immunostaining. However, the FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 fusion was not detected by staining or in Western blots even when using different anti‐FLAG antibodies, so the persistence of the expressed protein beyond G2/M phase cannot be judged. Expression of FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 was verified in a membrane fraction of the pPI4Kβ1:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 line (Appendix Fig S2A and B) using a custom anti‐PI4Kβ1 antibody against the C‐terminal fifteen amino acids of PI4Kβ1 (TRQYDYYQRVLNGIL) re‐raised as reported previously (Preuss et al, 2006). The specificity of this antibody was verified by analyzing crude extracts from wild‐type Arabidopsis, the pi4kβ1 single mutant, or the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. The antibody recognized a band at 130 kDa corresponding to the size of the PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 proteins in wild‐type protein extracts, but not in pi4kβ1 or pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutants (Appendix Fig S2A), indicating the antibody specifically recognized PI4Kβ1. While the antibody detected PI4Kβ1 on immunoblots, PI4Kβ1 was not detected by immunofluorescence in wild‐type samples nor in the partially complemented double mutants expressing PI4Kβ1 from the pKNOLLE promoter (Appendix Fig S2C). Instead, the antibody gave rise to unspecific signals in interphase cells even of root cells of pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants (Appendix Fig S2C), so the persistence of the PI4Kβ1 protein expressed from the pKNOLLE promoter could not be judged. As a kinase‐dead variant of PI4Kβ1 was previously unable to rescue the phenotypes of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Antignani et al, 2015), we concluded from the combined complementation data that one function of PI4Kβ1 in Arabidopsis is the formation of PtdIns(4)P during somatic cytokinesis, but that PI4Kβ1 also has regulatory functions in interphase cells.

Figure 1. Cytokinetic defects of the Arabidopsis thaliana pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- The growth phenotype of the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant can be complemented by ectopic expression of PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 or by mCherry‐tagged PI4Kβ1 expressed from a genomic fragment. Plants shown are 1 month old. Scale bar, 10 cm.

- The irregularities in the pattern of root epidermal cell division orientation of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant are also complemented by ectopic expression of PI4Kβ variants, as shown by propidium iodide (PI) staining of 5‐day‐old roots. Arrowhead, oblique cell wall. Insets, magnifications of areas showing cell wall stubs. Scale bars, 50 μm.

- Quantifications of cell wall stubs, oblique cell walls and root meristem size (wild type, n = 15 roots; pi4kβ1, n = 15 roots; pi4kβ2, n = 14 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 18 roots; pPI4Kβ1:PI4Kβ1, n = 14 roots, pPI4Kβ2:PI4Kβ2, n = 15 roots). n.d., not detected. Data are mean ± SD. Lowercase letters indicate a significant increase of oblique cell walls (Welch ANOVA with Games‐Howell post hoc test; P < 0.0001) or a significant reduction of root meristem size in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (one‐way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD; P < 0.001).

- Complementation of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 phenotype by functional FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 expressed from the intrinsic pPI4Kβ1 or the pKNOLLE promoters, as indicated, shown for 1‐month‐old plants. Scale bar, 10 cm. Complementation with the pKNOLLE‐driven construct indicates functionality of PI4Kβ1 during cell plate formation in G2/M phase.

- PI staining of pKNOLLE:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 expressed in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant background indicates rescue of cytokinetic defects. Arrowhead, cell wall stub in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Scale bars, 50 μm. Further phenotypic aspects of the pKNOLLE:FLAG‐PI4Kβ1‐complemented double mutants can be seen in Appendix Fig S1.

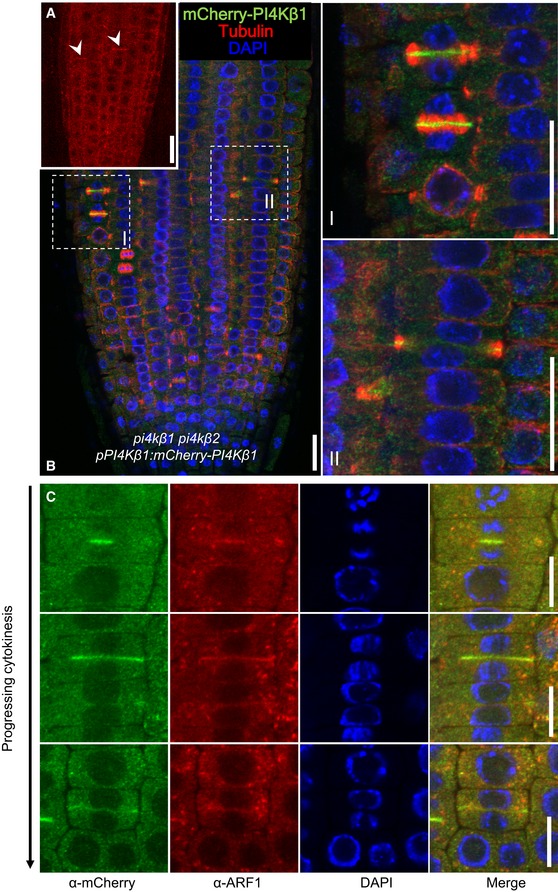

The fluorescence of the functional mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 fusion expressed in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant decorated the cell plate of cytokinetic root cells in vivo (Fig 2A). As in vivo fluorescence was weak, subsequent whole‐mount immunostaining was performed and clearly showed mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 residing in cytokinetic cells at the cell plate (Fig 2B) from early to late cytokinesis and concentrated at the leading edges of the cell plate (Fig 2B [I], [II]). No signal was observed using wild‐type plants as a negative control (Appendix Fig S3), indicating the mCherry detection was specific. Under its intrinsic promoter, the mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 fusion was also expressed in prophase and metaphase, and the marker fluorescence showed punctate and diffuse localization patterns (Fig 2B), suggesting PI4Kβ1 also has functions outside cytokinesis. Therefore, the localization of mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 was further evaluated by immunofluorescence relative to the TGN marker, ARF1 (Boutté et al, 2010), and the fluorescence patterns largely co‐localized (Fig 2C), consistent with previously reported TGN localization of PI4Kβ1 (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011).

Figure 2. PI4Kβ1 localization at the cell plate and the TGN during cytokinesis in Arabidopsis root cells.

- In vivo localization of mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 expressed from the pPI4Kβ1 promoter in root tips of 5‐day‐old complemented pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 plants. The mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 distribution was imaged using a Zeiss LSM880 in Airyscan Virtual Pinhole (VP) mode with the pinhole set to 2. Arrowheads, nascent cell plates decorated by mCherry‐PI4Kβ1. Scale bar, 20 μm.

- Whole‐mount immunostaining of 5‐day‐old seedlings expressing mCherry‐PI4kβ1 in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant background using anti‐tubulin (red) and anti‐mCherry (green) antibodies, and DAPI (blue). (I), (II), magnifications of regions marked in b, representing early and late cytokinetic stages. Scale bars, 20 μm.

- Relative localization of mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 and the TGN marker, ARF1, during cytokinesis. Four‐day‐old seedlings were immunostained with anti‐mCherry (green) and anti‐ARF1 (red) antibodies. Scale bars are 10 μm. Further controls for the use of the anti‐mCherry antibodies can be seen in Appendix Fig S3.

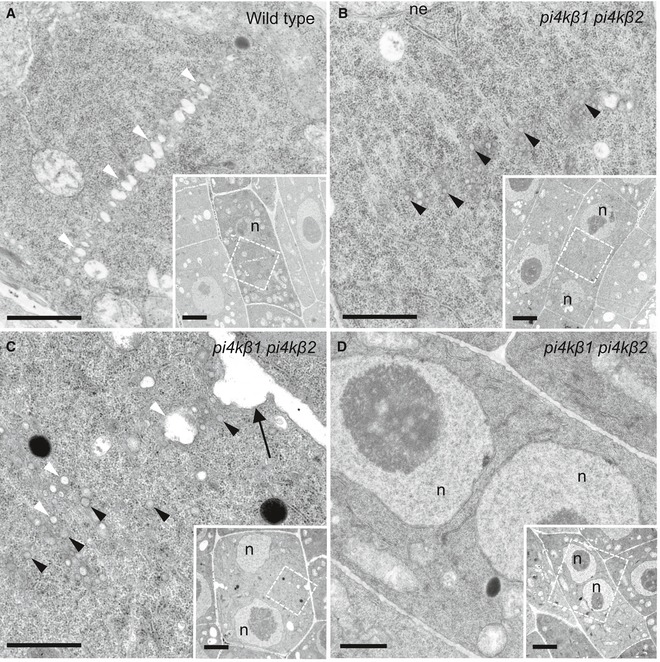

As in cytokinetic cells PI4Kβ1 was localized to leading edges of cell plates (Fig 2B and C), the main area where incoming vesicles fuse to contribute to cell plate growth (Seguí‐Simarro et al, 2004), one would expect that fusion of vesicles at the cell plate might be altered in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutant. As expected, using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) we did find numerous unfused vesicles in cytokinetic root cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutant and the cell plate was not well defined (Fig 3A and B; black arrowheads), in contrast to coordinated fusion of vesicles at a clearly defined nascent cell plate in wild‐type cells (Fig 3A). We further observed that cell wall stubs were surrounded by two types of unfused vesicles (Fig 3C; black and white arrowheads, respectively). In addition, we also observed totally blocked cytokinesis, i.e., no cross‐walls at all (Fig 3D). Overall, the TEM analysis confirms that pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutants display previously reported membrane trafficking defects (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011), which we further explored.

Figure 3. Ultrastructure of cytokinetic defects in root tips of Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants.

-

A, BThe ultrastructure of cytokinetic defects was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy of 5‐day‐old root tip meristems. Images shown are from three roots (wild type) and seven roots (pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant). In wild‐type controls (A), vesicles fused at the cell division plane to give rise to the tubular network (TN) of a nascent cell plate. White arrowheads, fused vesicles at the division plane. n = 8 cells. In the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (B), vesicles were delivered to the cell division plane at a similar stage as wild type but did not fuse. The nuclei of both wild‐type and double mutant cells were at telophase or interphase, as judged by the presence of decondensed chromatin and a nuclear envelope. At this stage, failed cell plate formation was never seen in wild type (A). Black arrowheads, unfused vesicles. n = 6 cells.

-

CUnfused vesicles clustered around a cell wall stub (arrow). White arrowheads, light vesicles; black arrowheads, dark vesicles; black arrow, cell wall stub. n = 8 cells.

-

DNo cross‐wall was seen in this cell with two nuclei. n = 6 cells.

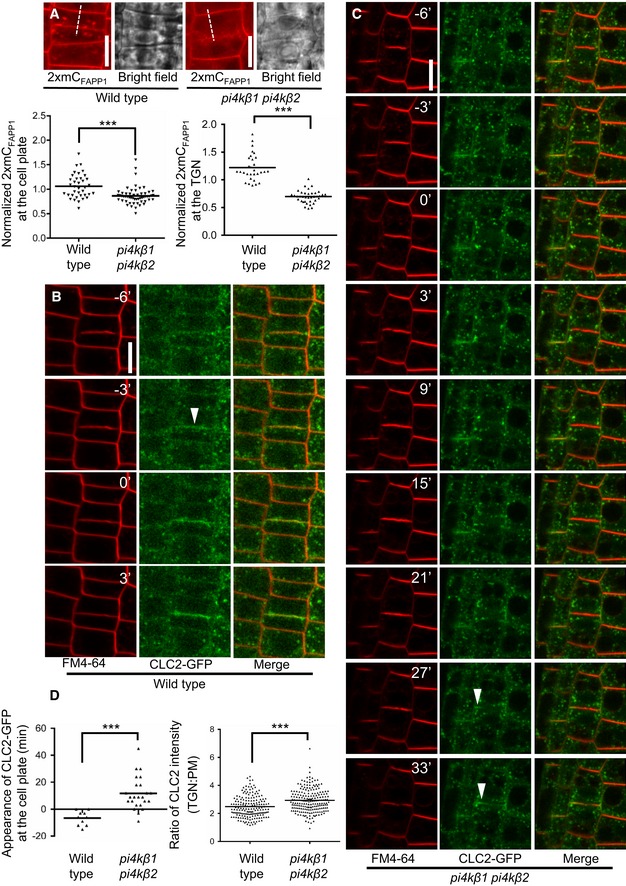

PtdIns(4)P production and clathrin‐mediated endocytosis at the cell plate are impaired in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant

The association of a biosensor for PtdIns(4)P, 2xmCherryFAPP1‐PH (Vermeer et al, 2009; Simon et al, 2014), with the cell plate appeared reduced in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant compared to wild‐type controls at equivalent stages at the end of cytokinesis (Fig 4A), suggesting a PtdIns(4)P‐dependent defect. It should be noted that in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, the cell plate appeared slightly diffuse, possibly interfering with precise quantification of reporter intensities. As furthermore the in vivo use of fluorescent reporters for phosphoinositides has its caveats (Balla et al, 2000; Varnai & Balla, 2008; Heilmann, 2016; Gerth et al, 2017), and specifically the FAPP1‐PH module may also bind to the TGN‐associated ARF1 protein (Godi et al, 2004; He et al, 2011; Liu et al, 2014), we confirmed by immunofluorescence that the distribution of ARF1 was not altered in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Appendix Fig S4). With these reservations, a decreased abundance of the 2xmCherryFAPP1‐PH reporter was observed at the cell plate (Fig 4A). This pattern is particularly interesting, because the fluorescence intensity of the reporter at the plasma membrane did not considerably change, suggesting that PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 might not contribute substantially to the production of PtdIns(4)P at the plasma membrane. This notion is also supported by biochemical analyses of lipid levels in Arabidopsis root tissue, which consists mostly of interphase cells. These analyses did not indicate a significant difference in PtdIns(4)P abundance between wild type, pi4kβ1 and pi4kβ2 single mutants, the double mutant, or complemented lines ectopically expressing either PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 from their respective intrinsic promoters in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant background (Appendix Fig S5). At the cell plate of pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant cells, the 2xmCherryFAPP1‐PH signal was reduced but not fully abolished (Fig 4A, left plot), consistent with a localized and/or limited contribution of PI4Kβ isoforms to PtdIns(4)P production even in this specialized compartment. Interestingly, the association of the 2xmCherryFAPP1‐PH with the trans‐Golgi‐network (TGN) was also reduced in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 4A, right plot). Given that in yeast the knockdown of the PI4K, Pik1p, inhibits the recruitment of clathrin to the Golgi (Gloor et al, 2010) and that plant phosphoinositides have previously been linked to clathrin dynamics (Ischebeck et al, 2013; Gerth et al, 2017), we hypothesized that clathrin dynamics may be affected in the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. While defective secretion has previously been reported for the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutant (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011), we therefore investigated whether additionally endocytosis and/or clathrin recruitment might be impaired. To test this hypothesis, a clathrin light chain 2 (CLC2)‐GFP marker (Konopka et al, 2008) was introgressed into the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant and its association with the cell plate was analyzed by live‐cell time‐lapse imaging in root cells undergoing cytokinesis (Fig 4B–D, Movies EV1 and EV2). The timing of fluorescence patterns for wild type and mutant is reported relative to the time point when the cell plate attaches to the peripheral plasma membrane, here defined as t0 (Fig 4B and C). In cytokinetic cells of wild‐type controls, the CLC2‐GFP marker was recruited at ~−6.6 ± 5.3 min relative to t0 (Fig 4B and D). In contrast, in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant the recruitment of CLC2‐GFP to the cell plate was significantly delayed and only occurred ~11.6 ± 12.1 min after the cell plate attached to the plasma membrane (Fig 4C and D). Immunostaining performed during advanced cytokinetic stages showed an association of CLC2‐GFP with the cell plate for 98.1% of analyzed cells (n = 53) of wild‐type controls, but only for 27.0% of analyzed cells (n = 126) of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, confirming reduced association of CLC2‐GFP with the cell plate in the mutant (Appendix Fig S6). The reduced or delayed recruitment of CLC2‐GFP to the cell plate of cytokinetic cells was accompanied by an enhanced intensity of the CLC2‐GFP marker at the TGN (Fig 4D, right plot), as observed by immunofluorescence experiments, suggesting that the lesion in the PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 genes influenced processes also at the TGN, with possible regulatory consequences in or apart from cytokinesis. As effects of PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 on endocytosis might not be restricted to cytokinetic cells, we also tested clathrin dynamics in interphase cells of wild type and pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants by spinning disk microscopy (Appendix Fig S7) and found a significantly increased lifetime of 24 ± 8 s for CLC2‐GFP foci at the plasma membrane in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant vs. 19 ± 4 s in wild‐type controls (Appendix Fig S7C; P < 0.0001; n = 134 events for wild type; n = 130 events for pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2). Overall, the dynamics of CLC2‐GFP were thus found to be altered in both cytokinetic and interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Based on this notion, we next tested for defects in clathrin‐mediated endocytosis (CME). During cytokinesis, CME is involved in cell plate expansion and maturation (Ito et al, 2012). A key factor for cell plate formation during cytokinesis is the syntaxin KNOLLE, which requires CME for correct trafficking (Boutté et al, 2010). Based on immunostaining of cytokinetic cells, KNOLLE displayed increased association with the plasma membrane in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 5A and B), consistent with a defect in CME during cytokinesis (Boutté et al, 2010). Moreover, we observed significantly enhanced signals for KNOLLE (Fig 5C and D) and the auxin transporter PIN‐FORMED2 (PIN2)‐GFP (Fig 5E and F) at the cell plate of cytokinetic cells of pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants, indicating defects either in CME from or in vesicle fusion with the cell plate. An impairment of CME in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant was not restricted to cytokinesis, as the formation of BFA bodies decorated by PIN2‐GFP (Fig 5G and H) and the uptake of the membrane dye, FM 4–64, from the plasma membrane (Fig 5I and J) were also significantly reduced in interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Overall, our data indicate a function of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 in endocytosis of both cytokinetic and interphase cells. During cytokinesis, PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 is likely required at the cell plate for correct trafficking of key markers of cell plate formation, such as KNOLLE and PIN2. It is possible that a role of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 in the correct trafficking of these and other markers is in maintaining the delicate balance of secretion and retrieval of vesicles upon delivery of cargoes to the cell plate, as well as—possibly—the removal of excess deposited material from the cell plate.

Figure 4. Delayed recruitment of clathrin to the cell plate in the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

-

ATop: Cell plate‐associated fluorescence of the PtdIns(4)P reporter, 2×mCherryFAPP1‐PH, was monitored at the end of cytokinesis in 5‐day‐old wild‐type controls or pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants, as indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm. Bottom: The intensity of 2×mCherryFAPP1‐PH signals was quantified at the end of cytokinesis at the cell plate (left plot) and at the TGN (right plot). Signal intensities at the cell plate were recorded along the dashed lines indicated in the images and normalized to intensities at the apical plasma membrane (wild type, n = 37 cells, 24 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 55 cells, 41 roots). TGN intensities were recorded using the Airyscan VP mode, and the mean TGN intensity was normalized to mean apical and basal plasma membrane intensity (wild type, n = 30 cells, 22 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 37 cells, 31 roots). ***, significant differences (P < 0.0001) according to two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U‐tests.

-

B, CImage series from live‐cell time‐lapse analysis of CLC2‐GFP at the cell plate in roots of wild‐type or pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 seedlings costained with FM 4‐64, as indicated. Arrowheads, appearance of CLC2‐GFP at the cell plate. Times are given relative to the instance when the cell plate contacted the peripheral plasma membrane, defined as t0. Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are from median focal planes chosen from time‐lapse series recorded as 3D stacks. 3D projections of the t0 images for wild type and double mutant and results for CLC2‐recruitment based on immunostaining can be seen in Appendix Fig S6.

-

DLeft, quantification of the time of CLC2‐GFP appearance at the cell plate in wild type (B) or the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (C) (wild type, n = 10 cells, 7 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 24 cells, 19 roots). Right, quantification of CLC2‐GFP at the TGN in interphase cells. Five‐day‐old roots expressing CLC2‐GFP were subjected to immunostaining, and the mean TGN intensity was normalized to plasma membrane intensity (wild type, n = 14 cells, 2 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 15 cells, 2 roots). ***, a significant difference (P < 0.0001) according to a two‐tailed Student's t‐test.

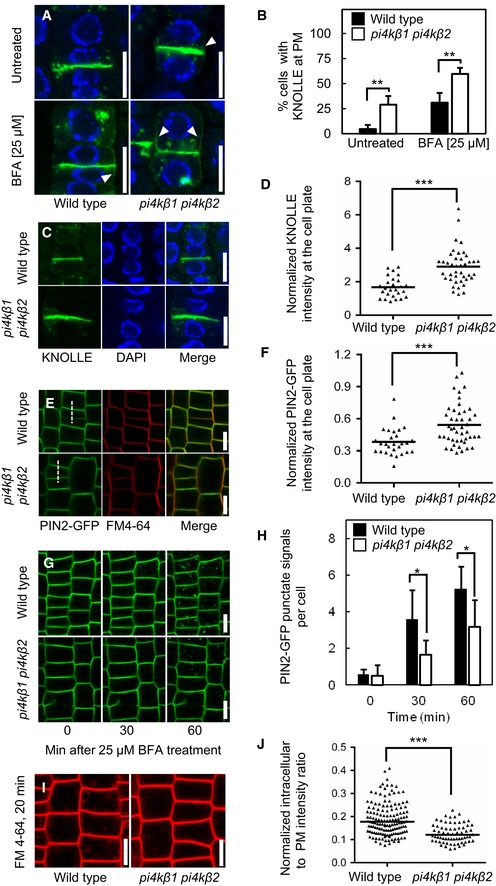

Figure 5. Impaired endocytosis in the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- Five‐day‐old seedlings were immunostained with anti‐KNOLLE (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). In the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, diffusion of KNOLLE occurred at the plasma membrane (arrowheads). Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantitative analysis of lateral diffusion of KNOLLE at the plasma membrane (PM) from (A). Data are mean ± SD from four independent experiments. **, a significant difference (P < 0.01) according to a two‐tailed Student's t‐test (untreated wild type, n = 97 cells, 25 roots; untreated pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 142 cells, 44 roots; BFA‐treated wild type, n = 126 cells, 28 roots; BFA‐treated pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 183 cells, 43 roots).

- Enhanced accumulation of KNOLLE at the cell plate at the end of cytokinesis in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Five‐day‐old seedlings were immunostained with anti‐KNOLLE antibodies (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantification of KNOLLE intensity at the cell plate from (C), normalized to the signal intensity of intracellular compartments. ***, a significant difference (P < 0.0001) according to a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U‐test (wild type, n = 26 cells, 20 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 41 cells, 37 roots).

- Enhanced accumulation of PIN2‐GFP at the cell plate at the end of cytokinesis in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Five‐day‐old seedlings were stained with 2 μM FM 4‐64 for 3 min at room temperature. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantification of PIN2‐GFP signal at the cell plate from (E), normalized to the intensity at the apical plasma membrane intensity, as indicated by the dashed lines. ***, a significant difference (P < 0.001) according to a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U‐test (wild type, n = 28 cells, 16 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 45 cells, 26 roots).

- Internalization of PIN2‐GFP was tracked over time in live roots pretreated with 50 μM CHX for 30 min, then washed, and incubated with 50 μM CHX and 25 μM BFA. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantification of punctate signals from (G) induced by BFA in wild type and pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants. Data are mean ± SD. *, a significant difference (P < 0.05) according to a two‐tailed Student's t‐test (wild type, n = 116 cells, 6 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 110 cells, 7 roots).

- Delayed internalization of FM 4‐64 from the plasma membrane in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Four‐day‐old seedlings were pulsed with 2 μM FM 4‐64 for 3 min on ice, and then, fluorescence was recorded for 20 min. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantification of intracellular FM 4‐64 signal from (i), normalized to apical and basal plasma membrane intensities. ***, a significant difference (P < 0.0001) according to a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U‐test (wild type, n = 116 cells, 6 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 66 cells, 9 roots).

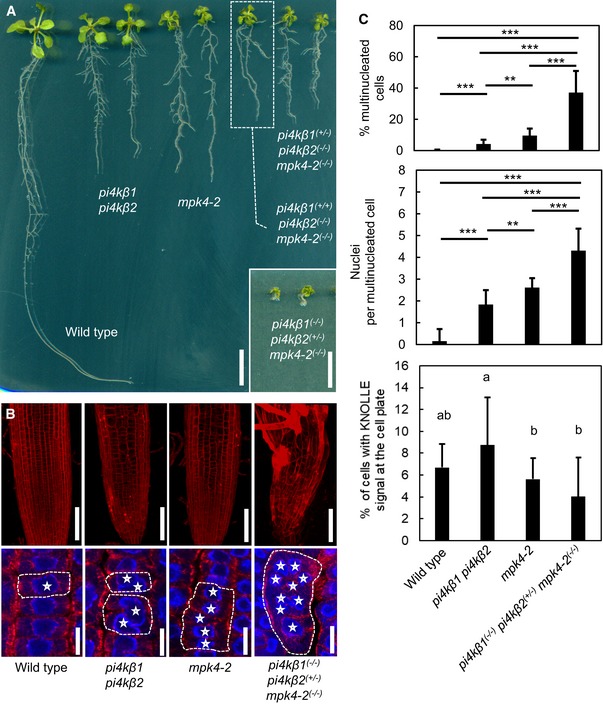

The Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant displays multinucleated cells and aberrant phragmoplasts

While impaired membrane trafficking might account for part of the cytokinetic defects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, we observed additional aspects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant phenotype that were not previously reported (Fig 6). In particular, an enhanced incidence of multinucleated cells and of cells with several persisting phragmoplasts was found in root cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 6A–C). These elements were not observed in wild‐type controls, indicating that further key aspects of cell division were impaired in the mutant. In cytokinetic wild‐type cells, immunostaining showed the phragmoplasts associated with the leading edges of the cell plate during late cytokinesis (Fig 6B), consistent with a model where central phragmoplast microtubules depolymerize and peripheral microtubules polymerize (Murata et al, 2013). In contrast, in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant the central areas of phragmoplasts were still solid even in late cytokinesis (Fig 6B), indicating that microtubules were ectopically stabilized. As phragmoplasts undergo dynamic transitions from initiation to solid, ring, and discontinuous stages during cytokinesis and finally disband to form cortical microtubules (Smertenko et al, 2017a), the defects in phragmoplast dynamics were assessed in more detail by time‐lapse imaging. To achieve this, we introgressed the microtubule marker mCherry‐TUA5 into the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant and performed live‐cell time‐lapse imaging on cytokinetic cells of wild‐type controls and double mutants (Fig 7, Movies EV3 and EV4). In cytokinetic cells of wild‐type controls, phragmoplasts persisted over a period of ~31.75 ± 12.00 min and underwent all cytokinetic stages (Smertenko et al, 2017a; Fig 7A) before disbanding to form cortical microtubule arrays (Fig 7A, Movie EV3). By contrast, in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, phragmoplasts persisted for a significantly longer time of ~72.95 ± 48.88 min (Fig 7B), appeared disordered, and did not display recognizable cytokinetic stages (Fig 7A, Movie EV4). Even though in cytokinetic cells of the double mutant microtubules were stabilized in the central zone of the cell plate and did not follow the leading edge, phragmoplast transition nonetheless progressed continuously to finally disband and form cortical microtubule arrays (Fig 7A). However, substantial proportions of microtubules lingered in an irregular pattern at the cell plate even after parts had already moved to a perinuclear or cortical orientation. It should be noted that cytokinetic defects in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant appeared to varying degrees, with cell plates ranging from close‐to‐normal to absent. For better comparison with the wild type, Fig 7A depicts a time‐lapse series of a mildly impaired cell plate, where the time between initiation and transition to cortical microtubules was roughly the same as in wild‐type controls. The data from our combined time‐lapse analyses on cytokinetic cells indicate a significant stabilization of phragmoplast microtubules in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant during cytokinesis (Fig 7B) (P < 0.001; n = 12 cells for wild type; n = 21 cells for pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2). The stabilization of phragmoplast microtubules in the central zone of the growing cell plate of cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant is further supported by the observation of an extended period of disk‐like phragmoplasts (Fig 7C) and from the extended duration between phragmoplast initiation and disbanding (Fig 7D) observed in these cells. Because of robust microtubule bundles in the phragmoplast, it is often difficult to measure the dynamics of phragmoplast microtubules. For interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, we determined dynamic parameters for cortical microtubules from cells of the root elongation zone by spinning disk microscopy (Appendix Fig S8). Most parameters of microtubule dynamics were globally unchanged in interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, including density, bundling, and the rates of polymerization, indicating there were no gross defects in microtubule arrays. However, the microtubular rate of shrinkage in interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant was at 8.3 ± 5.3 μm min−1 significantly lower than in interphase cells of wild‐type controls at 11.1 ± 7.1 μm min−1 (P < 0.05; n = 68, 6 roots for wild type; n = 53, 5 roots for pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2; Appendix Fig S8). While the information from the interphase cells does not pertain to phragmoplast microtubules in cytokinetic cells, the data are consistent with stabilized phragmoplast arrays observed in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, possibly in consequence of reduced shrinkage rates.

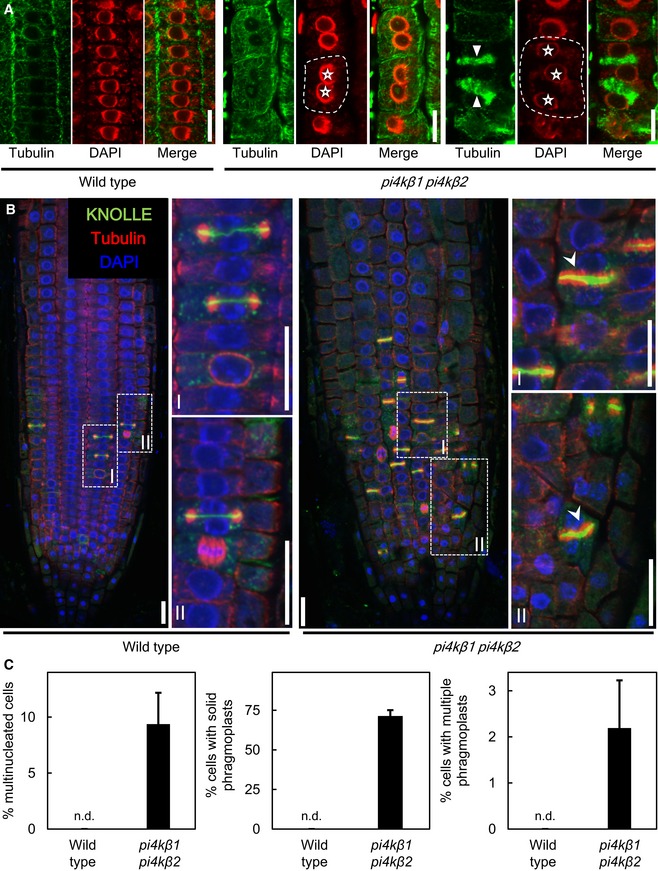

Figure 6. Multinucleated cells and aberrant phragmoplasts in root cells of the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- Immunostaining of meristem cells of 5‐day‐old plants using anti‐tubulin (green) counterstained with DAPI (false color red). Asterisks, multiple nuclei in one cell; arrowheads, multiple phragmoplasts in one cell. Dashed lines indicate the outlines of exemplary multinucleated cells. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Whole‐mount immunostaining of root tips of 5‐day‐old seedlings. Green, anti‐KNOLLE; red, anti‐tubulin; blue, DAPI. (I), (II), magnifications of areas highlighted in dashed boxes. Arrowheads, solid phragmoplasts with thicker cell plates. Scale bars, 20 μm.

- Quantification of the incidences of multinucleated cells, multiple phragmoplasts, and solid phragmoplasts during late cytokinesis (multinucleated cells: wild type, n = 316 cells, 29 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 673 cells, 44 roots; multiple phragmoplasts: wild type, n = 64 cells, 29 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 188 cells, 44 roots; solid phragmoplast in late cytokinesis: wild type, n = 41 cells, 29 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 89 cells, 44 roots). Data are mean ± SD from three independent experiments. n.d., not detected.

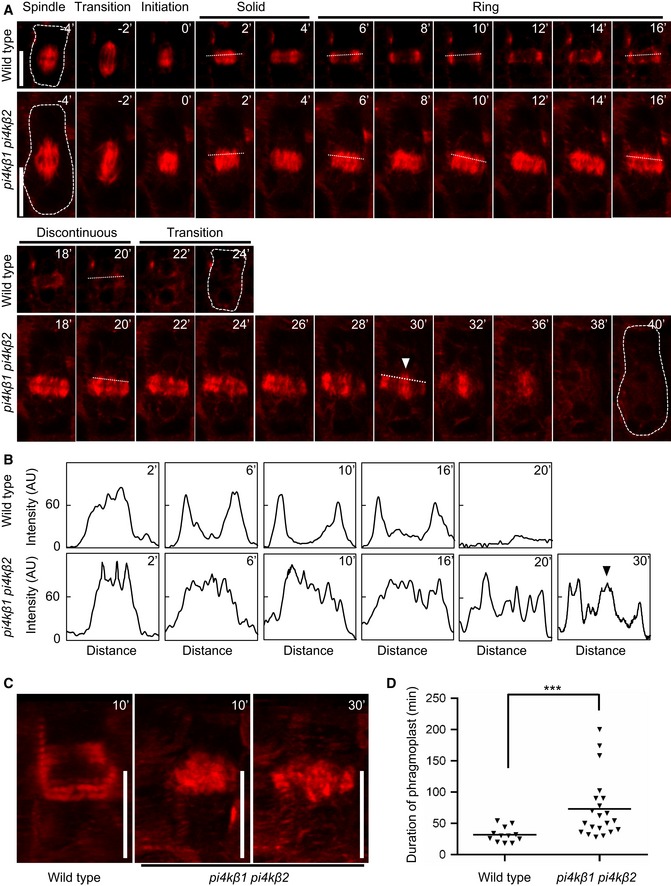

Figure 7. Disordered phragmoplast dynamics in cytokinetic root cells of the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- Five‐day‐old seedlings expressing mCherry‐TUA5 were imaged at 1 frame per 2 min. Times are given relative to the instance when the cell plate contacted the peripheral plasma membrane, defined as t0. Cells are outlined by dashed lines in the first and last frames of each series. White arrowhead, ectopic stabilization of microtubules in central phragmoplasts of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Plot profiles obtained from dashed lines marked in (A). Black arrowhead, ectopic stabilization of microtubules in central phragmoplasts of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- 3D projections from time points selected from (A), when the transition to a ring phragmoplast has occurred in wild type, but solid phragmoplast persisted in the double mutant. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Duration of phragmoplast persistence during cytokinesis, determined from initiation to disbanding. ***, a significant difference (P < 0.001) according to a two‐tailed Mann–Whitney U‐test (wild type, n = 12 cells, 9 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 21 cells, 16 roots).

MAP65‐3 mislocalizes in pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants

A key player controlling microtubule stability and phragmoplast dynamics is the microtubule‐associated protein 65‐3 (MAP65‐3), also known as PLEIADE (PLE; Müller et al, 2004). Loss‐of‐function of MAP65‐3 results in severe cytokinetic defects (Müller et al, 2004), whereas mutations in its isoforms MAP65‐1 and/or MAP65‐2 do not influence cytokinesis (Lucas & Shaw, 2012). In cytokinetic cells, MAP65‐3 is concentrated at the midline of the phragmoplast to cross‐link anti‐parallel microtubules during cytokinesis in a distribution pattern similar to that of PI4Kβ1, so we hypothesized that MAP65‐3 function and/or localization might be altered in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. To test this hypothesis, a functional GFP‐MAP65‐3 fusion (Steiner et al, 2016) was introgressed into the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 background, and the fluorescence distribution was analyzed in root cells by live‐cell time‐lapse imaging (Fig 8A–C, Movies EV5 and EV6). To better assess the exact positioning of the markers in cytokinetic cells, z‐stacks were recorded for each frame and used for 3D projections. The timing for both wild type and mutant is reported relative to the time point t0 when the cell plate would attach to the peripheral plasma membrane (Fig 8D). In cytokinetic cells of wild‐type controls, GFP‐MAP65‐3 initiated at ~−15 min, and between ~−12 min and ~−9 min, the marker would undergo a transition from a disk to a ring shape (Fig 8A and C), which decorated the leading edge of the expanding cell plate (Fig 8A, Movie EV5). Beyond ~6 min after t0, the GFP‐MAP65‐3 marker would dismantle from the cell plate (Fig 8A, Movie EV5). In cytokinetic cells of the double mutant, the GFP‐MAP65‐3 marker initiated at ~−12 min and subsequently persisted for an extended period of time beyond 24 min after t0 (Fig 8B). The transition from a disk to a ring shape occurred in the double mutant between ~15 min and ~18 min (Fig 8B and C, Movie EV6), and in contrast to wild‐type controls, the ring retained substantial signal in its center (Fig 8B and C, Movie EV6). Overall, prolonged disk‐shaped labeling of the cell plate by GFP‐MAP65‐3 was displayed in cytokinetic cells of the mutant until t0 and beyond, and the marker persisted substantially into the maturation phase of the cell plate. The in vivo findings were further supported by immunofluorescence, and in contrast to cytokinetic wild‐type cells, in which GFP‐MAP65‐3 formed ring‐like structures during late cytokinesis (100%, n = 43 cells), in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant GFP‐MAP65‐3 still persisted at the center of the midline (69.4%, n = 121 cells; Appendix Fig S9). Analysis of this pattern by super‐resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM) further detailed the differences in GFP‐MAP65‐3 distribution in 3D reconstructions (Fig 8E). While the relative timing cannot be defined with accuracy in the immunofluorescence experiments, the combined data indicate that the localization and turnover of MAP65‐3 were altered in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. The accumulation of MAP65‐3 at the midline of cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant would overstabilize noninterdigitating microtubules (nIMTs) of phragmoplasts to form interdigitating microtubules (IMTs), which are thought to be more stable than nIMTs (Ho et al, 2011), and prevent the formation of ring‐like phragmoplasts, consistent with the phragmoplast patterns observed in the double mutant (cf. Fig 7). We conclude that the defective phragmoplast progression in cytokinetic cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant may be a consequence of mislocalized and/or dysfunctional MAP65‐3, raising the question how PI4Kβ isoforms may contribute to controlling the function of MAP65‐3.

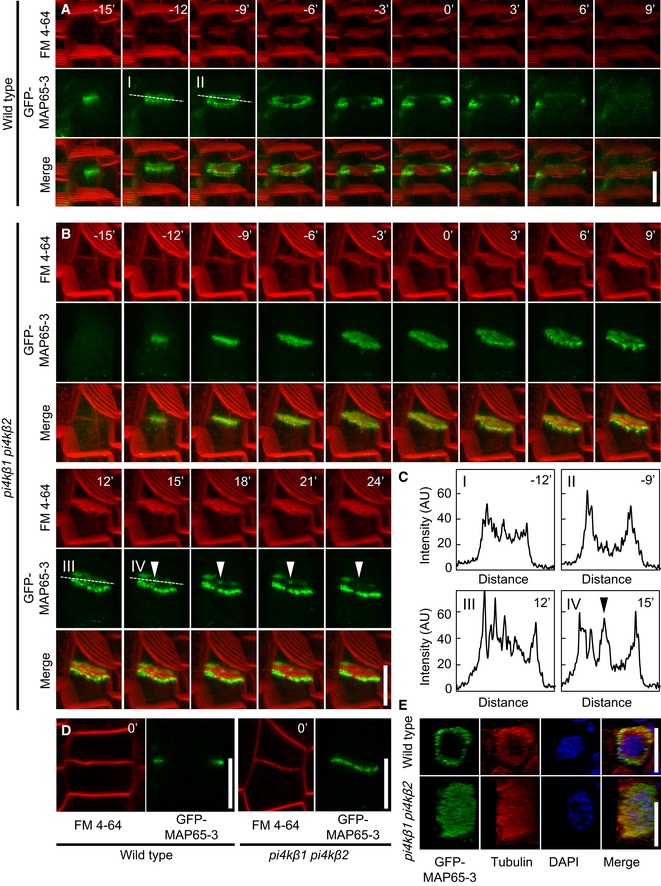

Figure 8. Mislocalization of GFP‐MAP65‐3 during cytokinesis in root cells of the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant.

- Image series of 3D projections of GFP‐MAP65‐3 costained with FM 4‐64 in root tips of 4‐day‐old wild‐type seedlings. The best angle for visualization was obtained by rotation of the x‐axis. Images are representative for 8 cells from 5 roots. Scale bar, 10 μm.

- Image series of 3D projections of GFP‐MAP65‐3 costained with FM 4‐64 in root tips of 4‐day‐old pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 seedlings. The best angle for visualization was obtained by rotation of the x‐axis. Images are representative for 11 cells from 10 roots. Arrowheads, persisting signal of GFP‐MAP65‐3 in the center of the cell division plane. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Plot profiles were obtained from medial confocal planes at time points displaying the transition from disk to ring phragmoplasts, marked by dashed lines in (A) and (B). Arrowhead, persisting signal of GFP‐MAP65‐3 in the center of the cell division plane.

- Medial confocal planes from z‐stacks from (A) and (B) demonstrating attachment of the FM 4‐64‐stained cell plate with the peripheral plasma membrane, defining t0. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- 3D reconstruction of ring‐ and disk‐shaped immunofluorescence patterns for GFP‐MAP65‐3 and microtubules, based on super‐resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM), costained with DAPI. Top panels, wild type; bottom panels, pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants. Scale bars, 10 μm.

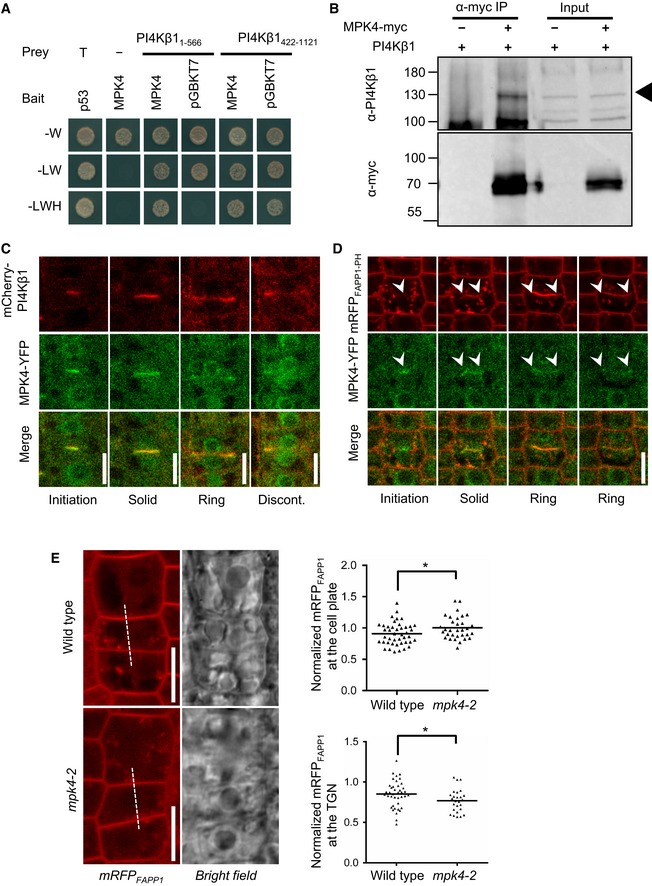

PI4Kβ1 and the MAP65‐3 regulator, MPK4, interact genetically, co‐immunoprecipitate, and interact in yeast and directly in vitro

Three MAP65 family members (MAP65‐1, MAP65‐2, and MAP65‐3) are well‐characterized targets for phosphorylation by the MAPK, MPK4 (Sasabe et al, 2011). MPK4 acts in the Arabidopsis equivalent of the tobacco NACK‐PQR pathway and is thus required for maintaining microtubule organization (Beck et al, 2010, 2011). Importantly, during cytokinesis MPK4 regulates the activity of MAP65‐3 by phosphorylation at the cell plate (Kosetsu et al, 2010). As we have previously described a regulatory link between MAPKs and phosphoinositide kinases in plants (Hempel et al, 2017), we next asked whether similarly MPK4 is functionally linked to the role of PI4Kβs in phragmoplast progression during cytokinesis. This hypothesis is supported by the similarity of the cytokinesis phenotype of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant reported here and the cytokinesis phenotype of the mpk4 mutant, which includes similar cytokinetic defects (Kosetsu et al, 2010; Beck et al, 2011), multinucleated cells, and stabilized microtubules (Beck et al, 2010). Other phenotypic similarities of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant and the mpk4‐2 mutant not related to cytokinesis have also previously been reported, including constitutive salicylic acid accumulation (Šašek et al, 2014; Antignani et al, 2015) and enhanced systemic acquired resistance (Petersen et al, 2000; Antignani et al, 2015), suggesting a functional relation between PI4Kβ isoforms and MPK4 also apart from cytokinesis. To test for a functional relation of PI4Kβ isoforms with MPK4, we first analyzed whether PI4Kβ1 or PI4Kβ2 genetically interacted with MPK4. For this purpose, the mpk4‐2 mutant was crossed with the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, and the offspring of self‐pollinated pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (+/−) plants was analyzed. The overall segregation pattern obtained from these crosses (Appendix Table S1) diverged significantly from Mendelian law (P < 0.0001). Among 181 progenies, we could not isolate a triple homozygous plant, suggesting that fertilization, the survival of gametes, or the viability of triple homozygotes might have been affected. It is interesting to note that the mpk4‐2 allele significantly repressed the distribution of the pi4kβ2 allele, or vice versa. The combined genotypes pi4kβ1 (+/−) pi4kβ2 (−/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) and pi4kβ1 (+/+) pi4kβ2 (−/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) displayed slightly reduced growth, whereas a pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) mutant was much smaller than either the mpk4‐2 or pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutants (Fig 9A). The pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) mutant displayed enhanced distortion of cell division orientation (Fig 9B). Furthermore, the proportion of multinucleated cells as well as the number of nuclei per multinucleated cell was significantly increased compared to the mpk4‐2 or pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutants (P < 0.001), suggesting that cytokinetic defects were more pronounced (Fig 9C). As the distortion of the tissue made it difficult to identify cell wall stubs, we evaluated the proportion of KNOLLE‐positive cells in the roots by immunostaining, revealing a significantly lower percentage of cytokinetic cells in the pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) mutant than in pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutants (Fig 9C). Taken together, these results suggest a synergistic genetic interaction of PI4Kβ1 and/or PI4Kβ2 with MPK4. While epistasis effects are not clear from the patterns observed, the data suggest that in vivo action of MPK4 and PI4Kβ1 and/or PI4Kβ2 converges at a common biological process. We therefore analyzed next whether PI4Kβ1 physically interacted with MPK4. For yeast two‐hybrid analysis, the PI4Kβ1 sequence was divided into two fragments, PI4Kβ11‐566 and PI4Kβ1422‐1121, as reported previously (Preuss et al, 2006). This was done, because the full‐length PI4Kβ1 has previously been shown to not interact with its partner protein, RabA4b, whereas the truncations showed positive interactions (Preuss et al, 2006). In these experiments, PI4Kβ11‐566 clearly interacted with MPK4 (Fig 10A). A positive result observed for PI4Kβ1422‐1121 cannot be interpreted, as the negative control for this fusion also gave a positive signal (Fig 10A), possibly resulting from non‐specific protein binding. The interaction of PI4Kβ1 and MPK4 was further corroborated by co‐immunoprecipitation (co‐IP) from plant protein extracts (Fig 10B). Using the re‐raised PI4Kβ1 antibody, PI4Kβ1 was detected in protein complexes immunoprecipitated from Arabidopsis seedlings expressing MPK4‐myc when MPK4‐myc was pulled down using an anti‐myc antibody (Fig 10B). Please note that the large apparent size detected for the MPK4 fusion results from the use of a previously reported functional MPK4 fusion (Berriri et al, 2012), which adds nine c‐Myc tags along with a polyhistidine tag and additional linker sequences. No PI4Kβ1 signal was detected upon immunoprecipitation from wild‐type seedlings used as a negative control (Fig 10B), demonstrating that the observed in planta association of PI4Kβ1 and MPK4 in a complex was specific. In cytokinetic Arabidopsis root cells, MPK4‐YFP co‐localized with mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 at the leading edge of the growing cell plate through different cytokinetic stages (Fig 10C). Furthermore, an mRFPFAPP1‐PH reporter for PtdIns(4)P also appeared synchronously with MPK4‐YFP at the cell plate, albeit not concentrated at the leading edge (Fig 10D). Together the data indicate that PI4Kβ1 and MPK4 either directly interact or occur in a protein complex with functional relevance for cell plate formation in cytokinetic cells.

Figure 9. Synergistic genetic interaction of Arabidopsis PI4Kβ1 and/or PI4Kβ2 with MPK4 during cytokinesis.

- Crosses of pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 and mpk4‐2 mutants resulted in combined genotypes with increased growth defects, as indicated. Fourteen‐day‐old seedlings are shown. Scale bars, 1 cm.

- Top: The severe growth defects of the combined genotypes were accompanied by increased tissue distortion, as shown by 3D projections after propidium iodide staining of root tips of 14‐day‐old seedlings. Scale bars, 100 μm. Bottom: Multinucleation of cells was increased in the combined genotypes, as evident from immunofluorescence of microtubules (red) counterstained with DAPI (blue). Asterisks, multiple nuclei in one cell. Dashed lines indicate the outlines of exemplary multinucleated cells. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Quantification of cytokinetic defects, as shown in the bottom panels of (B). Cytokinetic defects were enhanced in pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−) (for multinucleated cells, including the percentage of multinucleated cells and the average number of nuclei in multinucleated cells, both according to a Welch ANOVA with Games‐Howell post hoc test; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01 (wild type, n = 1,650 cells, 13 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 1,441 cells, 19 roots; mpk4‐2, n = 1,429 cells, 16 roots; pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−), n = 574 cells, 16 roots); and the incidence of cells displaying KNOLLE fluorescence at the cell plate according to a one‐way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD; P < 0.05, lowercase letters (wild type, n = 1,981 cells, 13 roots; pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, n = 1,758 cells, 19 roots; mpk4‐2, n = 1,721 cells, 16 roots, pi4kβ1 (−/−) pi4kβ2 (+/−) mpk4‐2 (−/−), n = 660 cells, 16 roots).

Figure 10. Functional association of PI4Kβ1 and MPK4 in a protein complex at the cell plate.

- PI4Kβ1 interacts with MPK4 in yeast two‐hybrid tests. MPK4 was used as a bait, while PI4Kβ1 was divided into two fragments to be used as prey. The results are representative for three independent experiments.

- In vivo co‐immunoprecipitation of MPK4 and PI4Kβ1 from 14‐day‐old plants. PI4Kβ1 was specifically co‐precipitated with MPK4‐myc using anti‐myc antibodies. Arrowhead, Migration of PI4Kβ1. The results are representative for three independent experiments.

- Coordination of MPK4‐YFP and mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 during cytokinesis in 5‐day‐old root meristem cells. MPK4 co‐localized with PI4Kβ1 from early to late cytokinesis and gradually concentrated at the leading edges of cell plates. Images were obtained with an LSM880 in Airyscan super‐resolution (SR) mode. Scale bars, 10 μm.

- Live‐cell time lapse of MPK4‐YFP and mRFPFAPP1‐PH during cytokinesis, obtained with an LSM880 in Airyscan resolution versus sensitivity (R‐S) mode. The time series is representative for six cells from five roots. Arrowheads indicate the initiation and leading edges of the growing cell plate. Scale bar, 10 μm.

- Left panels: The distribution of mRFPFAPP1‐PH was observed at the cell plate at the end of cytokinesis in root meristem cells of wild‐type controls (top) and mpk4‐2 mutants (bottom). Intensity profiles were recorded as indicated by the dashed lines. Scale bars, 10 μm. Right top, intensity of mRFPFAPP1‐PH at the cell plate normalized vs. the intensity at the apical plasma membrane (wild type, n = 43 cells, 34 roots; mpk4‐2, n = 32 cells, 28 roots). Right bottom, intensity of mRFPFAPP1‐PH at the TGN normalized vs. the intensity at the apical plasma membrane (wild type, n = 40 cells, 29 roots; mpk4‐2, n = 26 cells, 23 roots). *, a significant difference (P < 0.05) according to a two‐tailed Student's test.

Based on the genetic and physical interaction of MPK4 with PI4Kβ1, we next asked whether MPK4 would influence the formation of PtdIns(4)P in cytokinetic cells. To test this hypothesis, the mRFPFAPP1‐PH reporter was introgressed into the mpk4‐2 mutant background and the fluorescence intensity of the reporter was analyzed at the cell plate or the TGN (Fig 10E). In cytokinetic cells of the mpk4‐2 mutant, the ratio of cell plate‐associated vs. plasma membrane fluorescence was slightly but significantly increased (P < 0.05, n = 43 cells for wild type; n = 32 cells for pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2), indicating that MPK4 may exert an inhibitory effect on PtdIns(4)P production at the cell plate. At the same time, the reporter fluorescence at the TGN was slightly but significantly decreased (Fig 10E (P < 0.05, n = 40 cells for wild type; n = 32 cell for mpk4‐2). These experiments suggest functional interplay of MPK4 and PI4Kβ1 at the cell plate and at the TGN. While it remains to be seen whether the slight differences shown in Fig 10E are by themselves biologically relevant, MPK4 is known to regulate MAP65‐3 (Kosetsu et al, 2010) in cytokinetic cells. Our combined data suggest close functional interplay of MPK4, PI4Kβ1, and MAP65‐3 to control phragmoplast dynamics during somatic cytokinesis.

Discussion

The regulatory membrane phospholipid, PtdIns(4)P, has previously been detected at the cell plate and the TGN, and the Arabidopsis pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant has been shown to display cytokinetic defects. However, no focused study on the functional role of PtdIns(4)P in cell plate formation has been reported to date. Our data provide several lines of evidence for the function of PtdIns(4)P and PI4Kβ1 in cell plate formation of cytokinetic cells: a functional mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 fusion localized to the cell plate in vivo (Fig 2); loss of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 resulted in delayed recruitment of CLC2‐GFP to the cell plate (Fig 4B–D), in impaired CME during cytokinesis (Fig 5A–F), in ectopically stabilized phragmoplast microtubules (Figs 6B and 7), and in mislocalized MAP65‐3 (Fig 8); and the PI4Kβ pathway interacted genetically (Fig 9) and physically with the MAP65‐3 regulator, MPK4 (Fig 10A and B), which furthermore influenced PtdIns(4)P formation at the cell plate (Fig 10E). In sum, our results indicate a dual role for Arabidopsis PI4Kβ1 in the control of membrane trafficking via influencing clathrin recruitment to the cell plate, and in the control of phragmoplast microtubules in cytokinetic cells.

Impaired membrane trafficking is consistent with the defects in cell plate formation observed in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (cf. Figs 1 and 3). While PI4Kβs were reported to influence secretion in plants (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011), whether PI4Kβs were also involved in the regulation of endocytosis currently lacked evidence. Here, we found that PI4Kβs affected endocytosis in Arabidopsis through influencing clathrin recruitment to the cell plate of cytokinetic cells (Fig 4B–D), which is relevant for cell plate association of KNOLLE and PIN2 (Fig 5A–F). Roles of PI4Kβs in membrane trafficking, affecting both secretion and endocytosis, have also been found in animal cells (de Graaf et al, 2004; Kapp‐Barnea et al, 2006; Burke et al, 2014) and yeast (Audhya et al, 2000; Yamamoto et al, 2018), suggesting PI4Kβ proteins retained functionality for regulating both secretion and endocytosis in the course of evolution. By what molecular mechanism PI4Kβs influence clathrin recruitment in Arabidopsis remains to be examined in the future, for instance, to elucidate the possible involvement of the adaptor proteins TPLATE or AP‐2 (Di Rubbo et al, 2013; Yamaoka et al, 2013; Gadeyne et al, 2014), which recruit clathrin coats for endocytosis in Arabidopsis. Besides delayed recruitment of clathrin to the cell plate and to the TGN in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, we observed altered clathrin dynamics also in interphase cells (Appendix Fig S7). Several lines of evidence support the notion that a main function of PI4Kβs is in cytokinesis, including (i) the cytokinetic phenotype of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Preuss et al, 2006; Kang et al, 2011); (ii) the reduced intensity of mCherryFAPP1‐PH at the cell plate and the TGN (Fig 4A), combined with the failure to detect changes in PtdIns(4)P levels in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Appendix Fig S5), which suggests a limited, localized and/or transient contribution of PI4Kβ isoforms to global PtdIns(4)P production; (iii) the delayed recruitment of CLC2‐GFP to the cell plate in the mutant, based on time‐lapse imaging (Fig 4B–D); (iv) the peripheral plasma membrane association of KNOLLE in the double mutant, consistent with a CME defect during cytokinesis (Fig 5A and B); and (v) the enhanced abundance of KNOLLE and PIN2 at the cell plate in the mutant (Fig 5C–F). However, it appears that PI4Kβ isoforms also play a role in membrane trafficking and microtubule organization in interphase cells, as evident from the observations that (i) expression of PI4Kβ1 from the pKNOLLE promoter rescued only the cytokinetic but not the root hair defects of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 1 and Appendix Fig S1B); (ii) in the mutant the lifetime of CLC2‐GFP foci at the plasma membrane of interphase cells was increased (Appendix Fig S7); (iii) the formation of PIN2‐decorated BFA bodies in the mutant was reduced (Fig 5G and H); and (iv) in the mutant the internalization of FM 4–64 from the plasma membrane was reduced in interphase cells (Fig 5I and J). In sum, our data indicate a global functionality of PI4Kβ isoforms in the control of membrane trafficking at the TGN, with a predominant focus on cytokinetic cells. It is possible that in interphase cells, other PI4‐kinase isoforms can partially complement the genetic lesion of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant, so that the phenotype of the double mutant is mainly the observed cytokinetic defect. While the cytokinetic defects prompted us to focus on processes at the cell plate, the production of PtdIns(4)P and the abundance of the clathrin marker CLC2‐GFP were also altered at the TGN (Fig 4A and D), suggesting that PI4Kβ isoforms may influence the function of the TGN, with possible ramifications for cell plate formation.

Besides a role in membrane trafficking, we found evidence for an additional role of PI4Kβs in cytoskeletal control, because the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant also displayed solid phragmoplasts at late stages of cytokinesis in cytokinetic root cells (Figs 6B and 7), indicating that the turnover of microtubules may be impaired. Further analysis showed an ectopic association of MAP65‐3 protein with central areas of the maturing cell plate of cytokinetic cells (Fig 8). The depolymerization rate of microtubules was inhibited in interphase cells of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Appendix Fig S8), and decreased depolymerization rates are consistent with the occurrence of solid phragmoplast arrays in cytokinetic cells of these plants. Our data suggest that the defective lateral expansion of phragmoplasts in cytokinetic cells of pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants was a consequence of compromised regulation and/or localization of MAP65‐3 during cytokinesis to overstabilize microtubules at the center of the cell plate (Fig 7A–C). The central stabilization of microtubules is relevant, because the successful transition of phragmoplast microtubular arrays from solid to ring‐like structures is critical for cell plate expansion during cytokinesis (Strompen et al, 2002; Sasabe et al, 2006; Kosetsu et al, 2010). The defects in microtubule depolymerization in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutants might thus be a reason for impaired lateral expansion of the phragmoplast and failing cytokinesis (Nishihama et al, 2002; Sasabe et al, 2006), similar to the effects of inhibiting microtubule depolymerization with taxol, which also hinders phragmoplast expansion (Yasuhara et al, 1993). In both Arabidopsis and tobacco, the activities of the MAPKs, MPK4 (Beck et al, 2011), and NRK1 (Sasabe et al, 2006), respectively, are required for the control of phragmoplast dynamics during cytokinesis. For instance, malfunction of the HINKEL kinesin protein in the NACK‐PQR pathway also induces arrest of phragmoplast expansion and results in incomplete cytokinesis and cell wall stubs (Strompen et al, 2002), similar to the effects observed in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant. It is currently unclear whether the phragmoplast defects in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant are related to the membrane trafficking defects and the altered abundance of PtdIns(4)P at the TGN (Fig 4A). It is possible that microtubules, which orient vesicles in the correct position, may not be recycled efficiently if vesicle fusion is impaired or delayed (cf. Fig 3). However, the observation of MAP65‐3 mislocalization in the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 double mutant (Fig 8) suggests a direct regulatory effect. While the activity of MAP65‐3 is regulated at the cell plate of Arabidopsis cells by the NRK1 homolog, MPK4 (Kosetsu et al, 2010), our data suggest that PtdIns(4)P formation by PI4Kβ1 is required for the correct localization of MAP65‐3 at the leading edge of the expanding cell plate (Fig 8). Together with the data on genetic and physical interaction of PI4Kβ1 with MPK4 (Figs 9 and 10), we are led to speculate that all three proteins might act in a cell plate‐associated protein complex to regulate phragmoplast dynamics. Assuming that such a protein complex is required for correct progression of cytokinesis, then a missing partner might dissolve the complex and result in cytokinetic defects, as seen in the mpk4‐2, pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2, or map65‐3 mutants. Importantly, the other partners now released from the complex might then display added functionality in their respective alternative roles, e.g., in defense. Thus, it may be that reported correlations between failed cytokinesis and salicylic acid accumulation (Šašek et al, 2014; Antignani et al, 2015) or enhanced defense (Petersen et al, 2000; Antignani et al, 2015) might be due to a functional shift of the respective PI4Kβ or MPK4 proteins toward alternative cellular roles. Future work will be directed toward elucidating the functional interrelations between the proposed protein partners of the postulated complex and their effects on phragmoplast dynamics.

As a first step to elucidate the functional interplay of MPK4 and PI4Kβ isoforms, we found increased intensity of the PtdIns(4)P reporter mRFPFAPP1‐PH at the cell plate in mpk4‐2 mutants (Fig 10E) and decreased intensity of the reporter at the TGN (Fig 10E). However, the observed effects were slight and the biological significance of these observations remains currently unclear. Based on the recent report that PI4Kβ1 can be a target for phosphorylation by MPK4 (Latrasse et al, 2017), we performed a number of further experiments to delineate the molecular mechanism by which MPK4 might control PI4Kβ1 function. We could confirm this phosphorylation event in vitro using recombinant proteins (Appendix Fig S10A), and the modification of purified PI4Kβ1 by purified MPK4 supports a direct physical interaction of the proteins in vitro (cf. Fig 10). In analogy to the in vitro inhibition of the phosphoinositide kinase PIP5K6 by the MAPK, MPK6 (Hempel et al, 2017), we then tested the catalytic activity of PI4Kβ1 protein which had been prephosphorylated in vitro by MPK4, but found no change (Appendix Fig S10B). We also tested whether MPK4 exerted an effect on the subcellular localization of PI4Kβ1, but found no change in the localization of an mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 marker introgressed into the mpk4‐2 mutant background (Appendix Fig S10C). As these two obvious parameters (activity or localization) of PI4Kβ1 were not influenced by MPK4, the nature of the regulatory effect of MPK4 on PI4Kβ1 appears more complex and remains to be resolved in future studies.

Here, we demonstrate the interplay of two ancient signaling pathways, the NACK‐PQR pathway, and the phosphoinositide system of Arabidopsis in the context of membrane trafficking and somatic cytokinesis. While a role for phosphoinositides in controlling membrane trafficking has previously been shown, here we report an additional role for PtdIns(4)P in the control of microtubule dynamics, furthering our understanding of coordinated signaling pathways during somatic cytokinesis in plants and possibly other eukaryotic models.

Materials and Methods

Plant material, genotyping, and phenotyping

All materials used in this study were in the Arabidopsis Columbia background (Col‐0). pi4kβ1 (Preuss et al, 2006), pi4kβ2 (Preuss et al, 2006), and pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 (Preuss et al, 2006) were used as described before. The lines PIN2‐GFP (Ischebeck et al, 2013), 2×mCherryFAPP1‐PH (Simon et al, 2014), GFP‐MAP65‐3 (Steiner et al, 2016), MPK4‐YFP (Berriri et al, 2012), mCherry‐TUA5 (Endler et al, 2015), mRFPFAPP1‐PH (Vermeer et al, 2009), CLC2‐GFP (Konopka et al, 2008), and MPK4‐myc (Berriri et al, 2012) in this study have been described previously. mpk4‐2 (SALK_056245) was obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC, UK). All markers were crossed into corresponding mutants, respectively, and homozygous F3 lines were used.

For genotyping of pi4kβ1, pi4kβ2, and pi4kβ1×β2, pi4kbeta1‐LP, GAATAGAAGCCTGCAGGAAGGG, and pi4kbeta1‐RP, AGTGCCTGTGCTTGCTATTGTCC, were used for amplification of the PI4Kβ1 allele; pi4kbeta2‐LP, CATGGTGTCACATCTCACACAATTTGC, and pi4kbeta2‐RP, GTAAAGTGCCTGTGTCCTGCTTGAT, were used for amplification of the PI4Kβ2 allele; LB6316, TCAAACAGGATTTTCGCCTGCT, and pi4kbeta1‐RP or pi4kbeta2‐RP were used for amplification of the pi4kβ1 or pi4kβ2 specific allele. Genotyping of mpk4‐2 was performed as previously described (Kosetsu et al, 2010).

Molecular cloning and plant transformation

For genetic complementation of the pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutant, coding sequences (CDSs) of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 were amplified by PCR with the following primers: PI4Kβ1, forward: ATGCGTCGACATGCC GATGGGACGCTTTCTAT (underlined, SalI), reverse: ATGCGGATCCTCACAATATTCCATTTAAGAC (underlined, BamHI); and PI4Kβ2, forward: ATGCGTCGACATGCAGATGGCACAGTTTCT (underlined, SalI), reverse: ATGCGGATCCTCATCGTATTCCATTCAACAC (underlined, BamHI). The fragments were subsequently digested and ligated into pEntry vectors. Then, 1,360‐bp and 1,198‐bp genomic DNA sequences upstream of start codons of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2 were amplified, respectively, with the following primers: PI4Kβ1, forward: ATGCGGCCATTACGGCCATGTTTTCTCTCACACCCTCATA (underlined, SfiI), reverse: ATGCGGCCGAGGCGGCCCCTAATCAGCCAAGCATAAAAAGC (underlined, SfiI); and PI4Kβ2, forward: ATGCGGCCATTACGGCCCAACCGTCGGTGTTCCTCGTAA (underlined, SfiI), reverse: ATGCGGCCGAGGCGGCCTTTTGATGATCAGTCTTAGAATAA (underlined, SfiI). These two fragments were digested and ligated into pEntry vectors in front of CDSs of PI4Kβ1 and PI4Kβ2, respectively, called pPI4Kβ1‐PI4Kβ1 and pPI4Kβ2‐PI4Kβ2. The FLAG tag was also introduced into the N‐terminus of PI4Kβ1 by restriction site free cloning. Then, pPI4Kβ1‐PI4Kβ1, pPI4Kβ2‐PI4Kβ2, and pPI4Kβ1‐FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 cassettes were moved into pMDC123 binary vectors via LR reaction (Invitrogen), respectively.

For generation of pKNOLLE‐FLAG‐PI4Kβ1;pi4kβ1 × β2, 3,013 bp of KNOLLE cis‐regulatory elements upstream of the start codon was amplified using KN‐F: ATGCGGCCATTACGGCCCTTAGGATGGAGAGCCTTGCAGC (underlined, SfiI) and KN‐R: ATGCGGCCGAGGCGGCCCTTTTTCACCTGAAAGTCAAC (underlined, SfiI). Then, the native promoter pPI4Kβ1 of pPI4Kβ1‐FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 was excised by SfiI, and pKNOLLE digested by SfiI was inserted in front of the FLAG‐PI4Kβ1 cassette to produce pKNOLLE‐FLAG‐PI4Kβ1. Subsequently, pKNOLLE‐FLAG‐PI4Kβ1, which had been verified by sequencing, was transferred into the pMDC123 binary vector by LR reaction.

For mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 cloning, as genomic DNA of PI4Kβ1 (gPI4Kβ1) is quite large around 11,000 bp, mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 was divided into five fragments with the following five sets of primers using RF cloning: RF‐pi4kbeta1‐F1: CAACTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGGCCTCCTTCTTCAGGGAACGATGGAT, RF‐pi4kbeta1‐R1: CGTCTCGCATATCTCATTAAAGCAGCCTAACTTCCTCCATGGCAACAGTAC; RF‐pi4kbeta1‐F2: GTACTGTTGCCATGGAGGAAGTTAGG, RF‐pi4kbeta1‐R2: GCCAACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGAGTACCTGCAGAAGGTAACAGACCAAAG; RF‐pi4kbeta1‐F3: CTTTGGTCTGTTACCTTCTGCAGG, RF‐pi4kbeta1‐R3: GCCAACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGAGTAGTAAACAGCGAGAGTAAACGGTAGACT; and RF‐pi4kbeta1‐F4: AGTCTACCGTTTACTCTCGCTGTTTAC, RF‐pi4kbeta1‐R4: GCCAACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGAGTAGGATCCGAGTTAGTTACCGGG‐TAAATCAGGAGG. After assembly of whole‐genomic PI4Kβ1 into pEntry E vector, mCherry including a short linker SGPSG encoded by TCTGGTCCATCTGGT was amplified using the following primers: mCherry‐gPI4Kb1‐F: GGGCTTTTTATGCTTGGCTGATTAGGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGA, mCherry‐SGPSG‐gPI4Kb1‐R: AGATAGAAAGCGTCCCATCGGCATACCAGATGGACCAGACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGC (underlined, SGPSG). Then, it was fused at the N‐terminus upstream of the start codon of PI4Kβ1 via RF cloning. The construct was sequenced and moved into pMDC123 vector before transformation into Agrobacterium for further complementation analysis. The positive seedlings were selected with Basta and genotyped with gPI4Kβ1‐LP: TCCAGTCCCTAGACATGATTTGTCTGTA, and gPI4Kβ1‐RP: ATGGAAAGTTACCTGGTTGGGACC for the wild‐type allele‐specific fragment amplification; and LB6316: TCAAACAGGATTTTCGCCTGCT and gPI4Kβ1‐RP for the pi4kβ1 allele‐specific fragment amplification, respectively.

All vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain AGL0 and then transformed into pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 to check genetic complementation by floral dipping. Positive T1 seedlings were selected with Basta (Bayer) in soil or on 1/2 MS plates containing 10 μg/ml Phosphinothricin (Duchefa). T2 or T3 lines were used for further analyses.

Propidium iodide staining

Five‐day‐old or fourteen‐day‐old seedlings of wild type (Col‐0) and mutants were stained by propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) in H2O for 2 min, and then washed with water. The seedlings were mounted in water and immediately analyzed by confocal microscopy. We took z‐stacks from surface to median section of each root with 1 μm step size for quantification of cell wall stubs, oblique cell walls, and root meristem size. Cell wall stubs and oblique cell walls were quantified manually from all slices of z‐stacks. For measurement of meristem size, the median section of propidium iodide stained root was used, and the meristem size was measured from quiescent center to the first visible elongating cell.

Whole‐mount immunostaining

Immunostaining was carried out as described before (Sauer et al, 2006) with some modifications. In brief, seedlings were fixed in vacuo with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in PEM buffer (50 mM PIPES, pH 6.9, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgCl2) plus 0.05% (v/v) Triton X‐100 for 1 h, followed by three times of washing. The materials were partially digested using 2% (w/v) macerozyme R‐10 (28302, SERVA) in PEM buffer with 0.4 M mannitol at room temperature for 30 min–1 h, with subsequent three times of washing in PEM buffer and one time of washing in PBS buffer. Samples were permeabilized with 2% (w/v) IGEPAL CA‐630 and 10% (v/v) DMSO in PBS buffer for 1 h. The seedlings were washed with PBS three times and blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 30 min. Next, the samples were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 3% (w/v) BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C at the required concentrations, with successive washing. Then, they were labeled with secondary antibodies diluted in 3% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 2 h at room temperature with the adequate concentrations, followed by series of washing. Finally, samples were counterstained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 30 min. The samples were directly mounted in PBS and immediately observed. The concentrations for primary and secondary antibodies were used as follows:

Rat monoclonal anti‐α tubulin, clone YOL 1/34 (1:100, EMD Millipore; 1:2,000, Abcam); rabbit polyclonal anti‐KNOLLE (1:4,000, provided by Prof. Gerd Jürgens, Tübingen, Germany); rabbit polyclonal anti‐mCherry (1:2,000, ab167453, Abcam); rabbit polyclonal anti‐GFP (1:2,000, A11122, Invitrogen). All secondary antibodies were purchased from Abcam or Invitrogen: Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti‐rat IgG (H + L) (1:2,000, Abcam or Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti‐rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:2,000, Invitrogen).

For double immunostaining of ARF1 and mCherry‐PI4Kβ1 in which two primary antibodies were both raised from rabbit, a modified method (Wessel & McClay, 1986) was used. Seedlings were fixed, digested, and permeabilized as described above. Then, samples were blocked with 2% (v/v) donkey serum for 30 min and then incubated with anti‐ARF1 (AS08325, provided by Prof. Karin Schumacher, Heidelberg University, 1:2,000 diluted in 2% donkey serum) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with excessive goat anti‐rabbit monovalent F(ab) fragments (1:20, diluted in 2% donkey serum, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat# 111‐007‐003) overnight at 4°C to convert rabbit IgG to goat IgG. Subsequently, samples were postfixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde dissolved in PBS for 1 h, followed by blocking with 2% donkey serum for 1 h. Then, the first secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti‐goat IgG (H + L) (Invitrogen) were added to samples and incubated for 2 h. Next, samples were incubated with the rabbit anti‐mCherry antibodies (1:2,000, ab167453, Abcam) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti‐rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:2,000, Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the samples were counterstained with DAPI for 30 min. Negative controls without second primary antibodies were performed in parallel clearly showing no signal due to Alexa Fluor 488.

Protein expression and enrichment

The CDSs of MPK4, MKK6, and PI4Kβ1 were amplified and ligated into pGEX‐4T‐1 to produce GST‐tagged fusion proteins, respectively. Subsequently, a constitutively active kinase MKK6DE (S221D, T227E) was generated by mutation in the Ser (S221) and Thr (T227) residues in the activation loop in MKK6. All proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). Briefly, for the GST‐MPK4 and GST‐MKK6DE expression, the preculture of cells was diluted into 200 ml LB liquid medium in 1:50 and allowed to grow till OD600 reached 0.6–0.8 at 37°C. Then, 1 mM IPTG was added to the cell culture for protein expression for 6–8 h at 30°C. For GST‐PI4Kβ1 expression, the cells were grown till OD600 reached ∼1.0 at 37°C. Then, 5 ml of the cells was transferred into 200 ml of LB medium filled in a 1‐l flask containing 0.1 mM IPTG and incubated overnight at 25°C. Cells were harvested and purified with glutathione‐Sepharose 4B beads (Thermo), following the manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro protein phosphorylation

In vitro phosphorylation of proteins was assessed as described previously (Li et al, 2017). Recombinant GST‐tagged MPK4 (0.3 μg) was activated by incubation with recombinant MKK6DE (0.2 μg) in the reaction buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ATP and 1 mM DTT) at 30°C for 40 min. Activated MPK4 was then used to phosphorylate recombinant GST‐PI4Kβ1 proteins (3 μg, 1:10 enzyme substrate ratio) in the same reaction buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ATP, and 1 mM DTT) at 30°C for 30 min in the presence of 10 μCi γ‐[32P]ATP (Hartmann Analytic GmbH, Germany). Then, all proteins were loaded into SDS–PAGE gel and processed as described above.

In vitro lipid phosphorylation assay for PI4Kβ1 activity

The catalytic activity of PI4Kβ1 was assayed as described before (Cho & Boss, 1995). The prephosphorylated GST‐PI4Kβ1 (30 μl reactions) was added to 30 μl reaction buffer to give rise to final concentrations of 30 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM cold ATP, 1 mM Na2MoO4, 15 mM MgCl2, and 10 μCi γ‐[32P]ATP in the presence of 6 μg PtdInsP substrate presolubilized in 2% Triton X‐100. Reactions were incubated at RT for 1 h. Then, the reaction was stopped by adding 1.5 ml of CHCl3:MeOH (1:2, v/v). The lipids were extracted and analyzed by thin‐layer chromatography (TLC). The TLC plates were scanned by the BAS 1500 image analyzer (Fujifilm), and the intensity of phospho‐labeled PtdIns(4)P was determined by using Fiji software (https://fiji.sc/).

Yeast two‐hybrid analysis

PI4Kβ1422‐1121 and PI4Kβ11‐566 fragments were amplified using the following two pairs of primers: PI4Kβ1422‐1121‐F: ATGCCCCGGGTAGGGAGGGGTTTTTCAAAAAATTC (underlined, XmaΙ), PI4Kβ1422‐1121‐R: ATGCGGATCCCTCACAATATTCCATTTAAGACCC (underlined, BamHΙ); and PI4Kβ11‐566‐F: ATGCCCCGGGTATGCCGATGGGACGCTTTCTATC (underlined, XmaΙ), PI4Kβ11‐566‐R: ATGCGGATCCCATATGACGTTTCACATAACGC (underlined, BamHΙ). Fragments were digested and inserted into prey vectors pGADT7. The MPK4 CDS was isolated via PCR amplification using MPK4‐F: ATGCCCATGGAGATGTCGGCGGAGAGTTGTTTCG (underlined, NcoΙ), MPK4‐R: AT‐GCGGATCCCTCACACTGAGTCTTGAGGATTGA (underlined, BamHΙ). Then, MPK4 CDS was digested and moved into the bait vector pGBKT7. All constructs were verified by sequencing. Prey and bait vectors were co‐transformed into the yeast strain Y2H Gold using a LiAc‐mediated transformation protocol. Cells were selected by omitting corresponding amino acids. In order to test auto‐activation, MPK4 in bait vector pGBKT7 alone was also transformed into Y2H Gold and selected on the same media which only lacked tryptophane (Trp, W). All positive colonies were resuspended and diluted to OD600 of 0.5, of which 3‐μl drops were spotted onto media lacking Trp only or Trp and leucine (Leu, L) or Trp, Leu, and histidine (His, H) to check protein interaction and auto‐activation. The yeast was allowed to grow for 3 days at 30°C.

Generation of the rabbit anti‐AtPI4Kβ1 antibody

The AtPI4Kβ1 C‐terminus CTRQYDYYQRVLNGIL was synthesized (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium) as an antigen and cross‐linked to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) by an additional amino‐terminal cysteine (underlined). IgG was purified from rabbit serum and affinity‐purified against the column‐coupled antigen (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium). The antibody specificity was tested against protein extracts from wild type, pi4kβ1, and pi4kβ1 pi4kβ2 mutant plants before application in downstream experiments.

Co‐immunoprecipitation (Co‐IP) from Arabidopsis