Abstract

Objective:

Substance use services and supports have traditionally been funded without the benefit of a comprehensive, quantitative planning model closely aligned with population needs. This article describes the methodology used to develop and refine key features of such a model, gives an overview of the resulting Canadian prototype, and offers examples and lessons learned in pilot work.

Method:

The need for treatment was defined according to five categories of problem severity derived from national survey data and anticipated levels of help-seeking estimated from a narrative synthesis of international literature. A pan-Canadian Delphi procedure was used to allocate this help-seeking population across an agreed-upon set of treatment service categories, which included three levels each of withdrawal management, community, and residential treatment services. Projections of need and required service capacity for Canadian health planning regions were derived using synthetic estimation by age and gender. The model and gap analyses were piloted in nine regions.

Results:

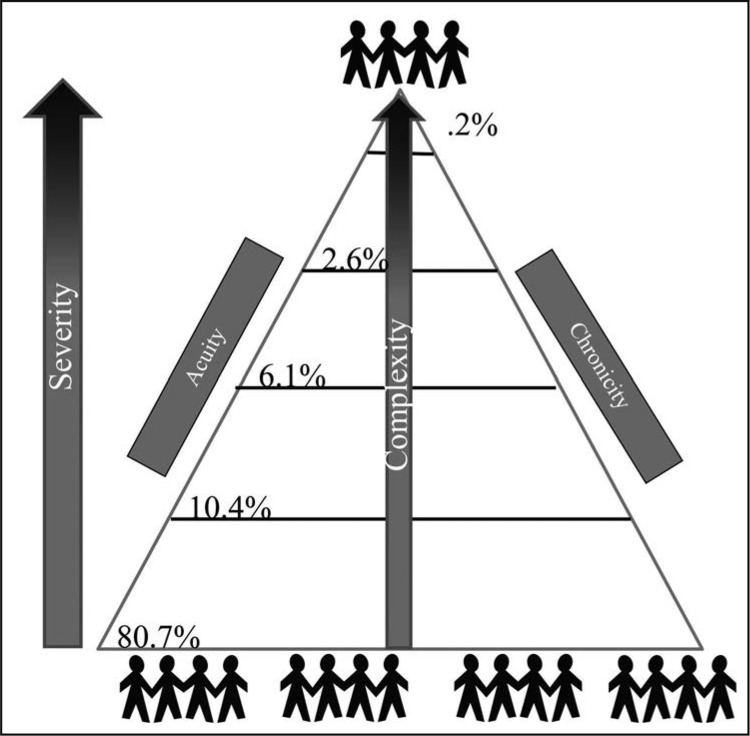

National distribution of need was estimated as Tier 1: 80.7%; Tier 2: 10.4%; Tier 3: 6.1%; Tier 4: 2.6%; and Tier 5: 0.2%. Pilot work of the full estimation protocol, including gap analysis, showed the results triangulated with other indicators of need and were useful for local planning.

Conclusions:

Lessons learned from pilot testing were identified, including challenges with the model itself and those associated with its implementation. The process of estimation developed in this Canadian prototype, and the specifics of the model itself, can be adapted to other jurisdictions and contexts.

Objectifs:

Les services liés à l’usage de substances ont traditionnellement été financés sans l’apport d’un modèle quantitatif global de planification étroitement ajusté aux besoins de la population. Cet article décrit la méthodologie utilisée pour développer et préciser les éléments-clés d’un tel modèle, donne un aperçu du prototype canadien qui en a découlé et propose des exemples ainsi que les leçons qui ont émergé dans le cadre de l’essai pilote.

Méthode :

Le besoin de traitement a été défini selon cinq catégories de sévérité du problème, élaborées à partir des données d’une enquête nationale et des niveaux anticipés de recherche d’aide qui sont estimés à partir d’une synthèse narrative des écrits scientifiques internationaux. Une démarche pancanadienne employant la méthode Delphi a été adoptée pour répartir la population des personnes en recherche d’aide dans un ensemble de catégories de services de traitement identifiées de façon consensuelle, parmi lesquelles on retrouve la gestion du sevrage, les services dans la communauté et les traitements résidentiels, chacune des catégories comprenant trois niveaux de traitements. Les projections des besoins et de la capacité de services requise pour la planification au sein des régions sociosanitaires canadiennes ont été estimées selon l’âge et le genre. Le modèle et l’analyse des écarts ont été testés dans neuf régions.

Résultats :

La répartition nationale des besoins a été estimée ainsi, soit niveau 1, 80,7%; niveau 2, 10,4%; niveau 3, 6,1%; niveau 4, 2,6%; niveau 5, 0,2%. Les travaux pilotes du modèle complet d’estimation, y compris l’analyse des écarts, ont montré que les résultats sont corroborés par d’autres indicateurs de besoins et ont été utiles pour la planification locale.

Conclusion:

Les leçons tirées des essais pilotes ont été identifiées, y compris les défis liés au modèle lui-même et ceux associés à son implantation. Le processus d’estimation développé dans ce prototype canadien ainsi que les spécificités du modèle lui-même peuvent être adaptés à d’autres contextes territoriaux.

Objetivos:

Servicios de consumo de sustancias y soportes tradicionalmente se han financiado sin el beneficio de un modelo de planificación comprensivo y cuantitativo alineados con las necesidades de la población. Este documento describe la metodología utilizada para desarrollar y refinar las características clave de dicho modelo, ofrece una visión general del prototipo canadiense resultante y ofrece ejemplos y lecciones aprendidas en el trabajo piloto.

Métodos:

La necesidad de tratamiento se definió de acuerdo con cinco categorías de gravedad del problema derivadas de los datos de encuestas nacionales y los niveles anticipados de búsqueda de ayuda que se estiman a partir de una síntesis narrativa de la literatura internacional. Se empleó un procedimiento Delphi pan canadiense para asignar esta población que buscaba ayuda a través de un conjunto acordado de categorías de servicios de tratamiento, que incluía tres niveles cada uno de los servicios de tratamiento de extracción, comunidad y tratamiento residencial. Las proyecciones de necesidad y la capacidad de servicio requerida para las regiones canadienses de planificación de la salud se obtuvieron por estimación sintética por edad y sexo. El modelo y el análisis de brechas se probaron en nueve regiones.

Resultados:

La distribución nacional de la necesidad se estimó como Nivel 1: 80.7%; Nivel 2: 10.4%; Nivel 3: 6.1%; Nivel 4: 2.6%; y Nivel 5: .2%. El trabajo piloto del protocolo de estimación completo, incluido el análisis de brechas, mostró que los resultados se triangularon con otros indicadores de necesidad y fueron útiles para la planificación local.

Conclusiones:

Se identificaron lecciones aprendidas de las pruebas piloto que incluyen desafíos con el modelo en sí y los asociados a su implementación. El proceso de estimación desarrollado en este prototipo canadiense y las características específicas del modelo en sí pueden adaptarse a otras jurisdicciones y contextos.

SUBSTANCE USE SERVICES and supports have traditionally been funded without a comprehensive planning model to help allocate resources equitably and according to population needs (Ritter et al., 2019a). This can result in perpetuated gaps in service relative to evolving population needs. The World Health Organization (WHO) Atlas (2017) reveals wide variation in type and capacity of substance use services on a global level, not explained by differences in the epidemiology of substance use and dependence. This highlights the lack of planning on the basis of need and calls for a more rational approach that can be applied in different contexts.

Decision support models and tools have been developed for individual client pathways (e.g., National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence, 2011) but rarely for treatment systems planning and evaluation. Building on the work of Ford (1985), Rush (1990) developed a needs-based planning model for Ontario, Canada—a model focused on services for people with alcohol-related problems. The goal was to estimate the number of people in need of services along a continuum of care within a defined planning area. The introduction to this supplement (Rush et al., 2019) summarizes key milestone initiatives that have been undertaken in parallel, or that have built on this early work.

An important development within this body of work, particularly since the mid-2000s, has been the shift from a “continuum model” describing hazardous, harmful, and dependent substance use to a “tiered model” that describes the epidemiology of substance use, including dependence and concomitant physical and psychiatric comorbidity, as a population health pyramid that relates to services of varying types and intensity (see Rush, 2010, for an overview of the evolution of the tiered model). Heavily influenced by the emergent view of substance use disorder as a chronic health condition (McLellan et al., 2000), researchers are seeing populations as varying along the dimensions of acuity, chronicity, and complexity and needing services of varying type, duration, and intensity in a stepped care framework. This thinking, coupled with advocacy for a broad systems approach to achieve population health impact (Babor et al., 2008; Institute of Medicine, 1990), has shaped much of the recent work in needs-based planning, including the present project.

In addition to the need for treatment systems to address a broad spectrum of severity with a network of services organized in a stepped care framework, there is a need to consider a host of barriers to seeking help, including accessibility and cost of services, as well as stigma and discrimination (Mojtabai, 2005; Wu et al., 2003a). This has resulted in relatively low help-seeking rates that vary by severity and subpopulation (e.g., Degenhardt et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2005). Self-directed efforts to reduce alcohol or drug consumption (Dunne et al., 2018), as well as natural recovery/remission without formal intervention by specialized treatment programs (Dawson et al., 2005; Sobell et al., 2000), are also important considerations for these planning models, although this does not obviate the need for planning and public investment in recovery-focused services and supports. It is also important to acknowledge that any treatment-oriented planning model should complement, not replace, a community focus on prevention and health promotion (Room et al., 2005).

The conceptualization and measurement of treatment “need” is also particularly important but challenging. For planning purposes, the need for substance use treatment can be defined normatively with diagnostic criteria or by self-report of perceived need (e.g., Meadows et al., 2000; see also Ritter et al., 2019b). The level of “unmet need” will vary with diagnostic criteria and the threshold of severity used to define need for treatment. To paraphrase Mechanic (2003), the crux of the matter is not the operational definition of need per se but rather to find a definition around which clinicians, decision makers, researchers, and other stakeholders can build consensus. This practical approach guided the present adaptation of the original Rush model. A “case-index” strategy was used that combined various indicators from population survey data to approximate an individual’s need for services resonating at a clinical level (i.e., had a high degree of face validity). A similar approach has frequently been used in the help-seeking literature (Evans-Polce & Schuler, 2016; Harris et al., 2014; Reavley et al., 2010) and in treatment system analysis (Barker et al., 2016), typically taking into account substance abuse or dependence symptom counts, indicators of psychological stress, and psychiatric comorbidity to develop the severity tiers. The approach has also been used in assessing the need for mental health services (Bijl et al., 2003; Harris et al., 2014), including housing-related supports (Goering et al., 2011)

Consistent with the tiered framework, in this kind of treatment capacity estimation process it is also necessary, for commissioning and funding purposes, to define services of different types and intensity that are deemed to be the optimal match for people at different levels of need. There is no global consensus on the definition of these service categories, in part because of varying treatment system histories and sociopolitical context (Klingemann & Hunt, 1998; Klingemann et al., 1992). Although common treatment functions can be articulated (e.g., early identification, assessment, withdrawal management, treatment intervention, continuing care), the model of service delivery to operationalize these functions is largely context bound (Rush & Urbanoski, 2019; Rush et al., 2014). There are, however, some guidelines for core components of substance treatment systems, such as those recommended by the United Nations Office on Drug and Crimes (UNODC, 2016) and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) levels-of-care (Gastfriend & Mee-Lee, 2003).

Between 2010 and 2014, Rush and colleagues extended the original “Rush model” to the pan-Canadian context (Rush et al., 2014). The present article aims to describe the methodology used to develop and refine key features of the needs-based planning model, provide an overview of the resulting prototype, and offer examples and lessons learned in pilot work.

Method

As with the original Rush model (Rush, 1990), four steps were followed to arrive at parameters and service capacity requirements based on population needs. These steps are summarized below.

Step 1: Determine the geographic area and size of the population served

The model was developed to estimate the required capacity of treatment services for people age 15 and over in Canada. At the outset of the project, the country was divided into 87 planning regions as the geographic basis for prioritization and funding of services; in some cases, one health authority covered the province/territory as a whole, and in other instances one province comprised multiple health authorities. This resulted in considerable variation in size and composition of the target population for planning purposes.

Step 2: Estimate the number of people at varying levels of risk and harm within the geographic area

Canadian Community Health Survey 1.2 data (Gravel & Béland, 2005) were used to estimate the number of people in the population age 15 and over at each of five levels of need described below. No health administrative data or monitoring systems were used. This survey was heavily oriented toward mental health and substance use, the latter covering use of a wide range of substances including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine/crack, amphetamines, heroin, ecstasy, inhalants, hallucinogens, and steroids. Based on responses to use of any of these substances, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)–based diagnostic module for substance abuse or dependence covered alcohol as well as any one of the illicit drugs (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Although tobacco use and pathological gambling were assessed, they were not factored into the present needs classification protocol because there is no consistent approach to planning and funding tobacco cessation or gambling services within the Canadian health systems.

The goal of this step was to develop need categories that were logical, had face agreement with present evidence and clinical experience of engaged stakeholders, and would be useful in separating groups of people according to their need for different services. Each survey respondent was uniquely classified into one of the following need categories:

Category 1. This category comprised abstainers and light to moderate drinkers or drug users who reported no problems related to their substance use.

Category 2. This category included heavy/binge drinkers or heavy drug users who reported few problems (three or fewer) related to their substance use. Although not meeting the DSM-IV criteria for alcohol or drug dependence, they were considered at moderate risk for health and/or social problems because of their patterns of substance use.

Category 3. Included here were substance users experiencing four or more substance use–related problems potentially indicative of substance abuse or dependence OR who fully met the DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse or dependence.

Category 4. This category comprised substance users who met the criteria of Category 3 AND one of the following criteria:

had a positive response to the survey question, “During the past 12 months, was there ever a time when you felt that you needed help for your emotions, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs but didn’t receive it?”

utilized formal health services because of mental health or substance use issues within the past 12 months;

showed significant interference in some aspect of their lives from their drug or alcohol use as indicated by the survey’s flag variables for alcohol or drug interference (at least 4 of 10 on any of the five interference questions each for drugs and alcohol).

Category 5. Substance users who met all the criteria of Category 4 AND all of the criteria listed below:

met the DSM-IV criteria for two or more (of five) mental diagnoses (major depression, manic episode, panic, social phobia, agoraphobia without panic);

had one or more mental disorders with significant interference (using the mental health interference flag variable) for at least one of these disorders; had a physical or mental condition that reduced ability sometimes/often in one of four areas (home, work, school, leisure).

These algorithms for severity categories were applied to the national data set using SPSS (Version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Individual standardized weights supplied in the Canadian Community Health Survey data set were used. Figure1 shows the resulting distribution of survey respondents within the five severity categories for Canada as a whole. The percentage in each age and sex subgroup was calculated nationally and synthetically estimated for each local planning area.

Figure 1.

Percentage of the Canadian population age 15 and over in the five severity categories

Step 3: Estimate the number of people from Step 2 that should be planned for treatment in a given year

We assumed two pathways into treatment: (a) naturalistic help-seeking, which refers to self-referral, service-referral, or mandated-referral, and (b) help-seeking via referral to treatment from services implementing systematic screening and case identification with a referral-to-treatment component (e.g., SBIRT, addiction liaison).

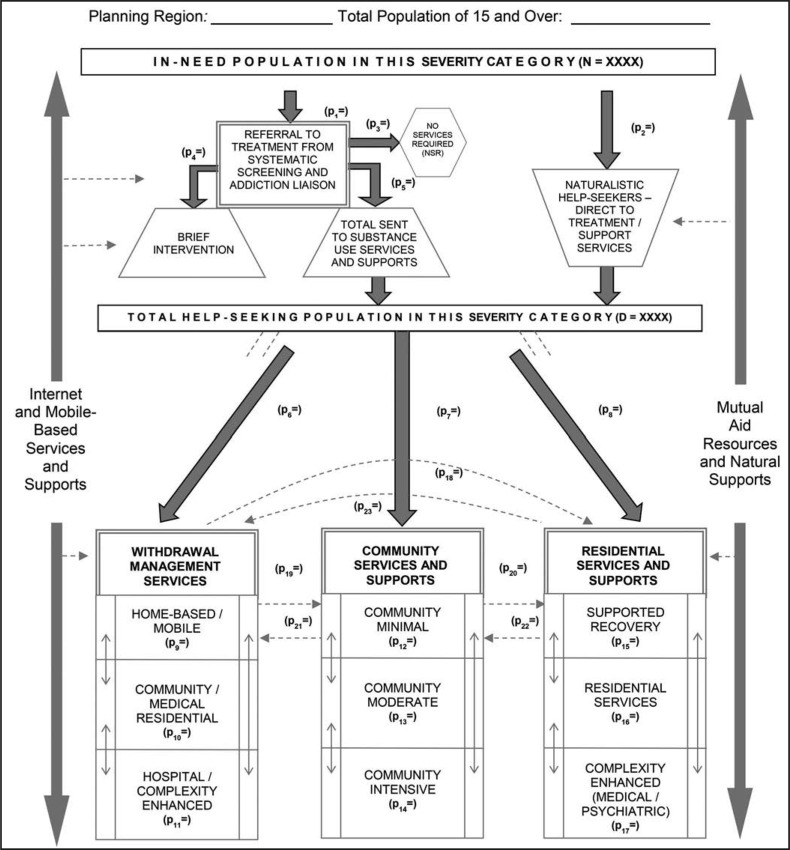

Figure 2 shows the treatment systems flow diagram; a diagram operationalized in a set of Excel spreadsheets for subsequent application. Population over age 15 is noted at the top of the diagram as well as the size of the in-need population. There would be one such diagram (or Excel sheet) for each of the five severity categories, because the distribution of the in-need population is considered to be different for different levels of severity. Parameters p1 to p23 are the proportions of estimated people accessing each level of service in the hypothetical treatment system. In some instances, the value of “p” represents the proportion of people transitioning from one service category to another (e.g., p18, which is the proportion transitioning from withdrawal management to residential services). In other instances, “p” refers to the proportion of people within a broad service category that will receive service in one of its subcategories (e.g., p9 to p11: the proportion of people needing withdrawal management that will receive service in the various subtypes of withdrawal management settings).

Figure 2.

Treatment system flow diagram: Schematic diagram of needs-based planning model for substance use services and supports

Naturalistic help-seeking (p2).

Naturalistic help seeking was estimated from a narrative review of the literature on help-seeking for substance use–related problems. The full details of the review are provided in Rush et al. (2014). Synthesis of this literature was challenging, given varying operational definitions of problem severity (e.g., abuse and/or dependence) as well as service use (i.e., specialized substance use services with inclusion or exclusion of such services as mental health, primary care, and less formal sources of help). The period under consideration for either or both substance use problems and use of services also varies across studies (i.e., lifetime or past-12-month rates). Moreover, many studies in this area merge reasons for mental health consultations with those for substance use problems, thereby preventing precise estimation of help-seeking for substance use concerns specifically. In the end, special consideration was given to three international studies that focused on 12-month substance dependence and 12-month use of specialized substance use services (Henderson et al., 2000; Wu & Ringwalt, 2004; Wu et al., 2003b) and one Canadian study that derived national estimates for 12-month substance dependence and help-seeking for “emotional, mental or alcohol/drug problems” (Urbanoski et al., 2007). Wu et al. (2003a) reported U.S.-based service use rates for alcohol or drug problems of 9% for uninsured populations. Wu and Ringwalt (2004) reported U.S.-based service use rates for alcohol-related problems of 12% for men and 12% for women. Henderson et al. (2000) reported on a large Australian sample and found the percentage using services among those meeting criteria for alcohol or drug dependence to be 14%. These estimates are in the same range as the 13.6% reported by Urbanoski et al. (2007) for a similarly defined Canadian population using the same survey as used for our derivation of the severity tiers. Based on these studies, our estimate of naturalistic help-seeking for substance use services was 13% of the in-need population for Category 4 severity.

The literature was then re-examined and findings organized by problem severity—one category higher than Category 4 based on mental health comorbidity, and one category lower based on meeting criteria for substance abuse but not dependence. Results tended to show a two-to threefold increase in the probability of help-seeking for the category of survey respondents meeting criteria for substance dependence plus one or more mental disorders (e.g., Jacobi, 2004), with increasing numbers of mental disorders being associated with an increase in help-seeking and perceived need for help (Mojtabai, 2009). The estimate for Category 5 in the needs-based planning model was, therefore, increased by a factor of 2.5 to yield an estimate of 32.5%.

The few studies that separated cases for substance abuse, but not dependence, generally showed a twofold decrease in the rate of help-seeking for the less severe group (e.g., Cunningham & Breslin, 2004). We considered this population to be the most similar to our Category 3 severity and derived an estimate of 6% help-seeking. No study reported data on help-seeking for substance use problems for cases below the threshold of substance abuse or dependence criteria (e.g., harmful or hazardous drinking or drug use). Based on the proportionate increases/decreases in help-seeking across the severity categories three to five, an estimate of 2% was projected for Category 2.

Help-seeking via systematic screening (p1, p3–p5).

In Figure 2, parameters p1 and p3–p5 refer to treatment entry via systematic screening efforts that aim to triage individuals toward either low intensity brief interventions or referral for assessment and higher intensity treatment if needed. Examples of these service models include formal screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment initiatives (SBIRT; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013) or formal addiction liaison services in hospital or emergency services (Blanchette-Martin et al., 2016). Beyond the effectiveness of the brief interventions themselves, a review of the relevant literature indicated the high potential of such initiatives for identifying people needing substance use treatment and engaging them in services (e.g., D’Onofrio & Degutis, 2010; Grothues et al., 2008; Madras et al., 2009). However, the evidence was also clear that there exist many challenges for implementing these care pathways, despite strong evidence of efficacy (Anderson et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2010; Nilsen et al., 2006; Roche & Freeman, 2004; Williams et al., 2011). Given their limited implementation in the Canadian context, the planning model included “place-holder” parameters p1 and p3 to p5, for the present, valued at zero.

Step 4: Estimating the number of individuals that will require service in each service category

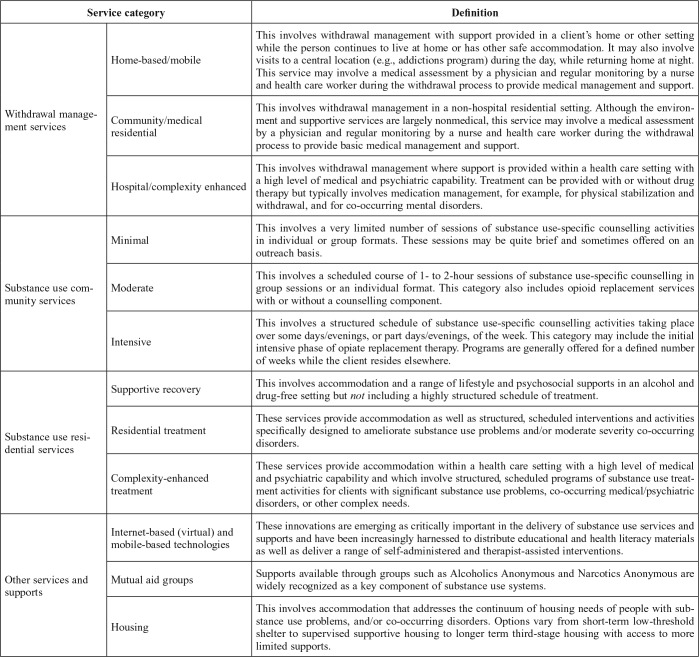

The starting place for projecting specific capacity requirements was the Service Category described in Table 1 and developed in close consultation with a multidisciplinary, pan-Canadian Project Advisory Committee. Although pan-Canadian in nature, they align with other international guidelines (Gastfriend & Mee-Lee, 2003; UNODC, 2016).

Table 1.

Categories of substance use services and definitions

| Service category |

Definition | |

| Home-based/mobile | This involves withdrawal management with support provided in a client’s home or other setting while the person continues to live at home or has other safe accommodation. It may also involve visits to a central location (e.g., addictions program) during the day, while returning home at night. This service may involve a medical assessment by a physician and regular monitoring by a nurse and health care worker during the withdrawal process to provide medical management and support. | |

| Withdrawal management services | Community/medical residential | This involves withdrawal management in a non-hospital residential setting. Although the environment and supportive services are largely nonmedical, this service may involve a medical assessment by a physician and regular monitoring by a nurse and health care worker during the withdrawal process to provide basic medical management and support. |

| Hospital/complexity enhanced | This involves withdrawal management where support is provided within a health care setting with a high level of medical and psychiatric capability. Treatment can be provided with or without drug therapy but typically involves medication management, for example, for physical stabilization and withdrawal, and for co-occurring mental disorders. | |

| Minimal | This involves a very limited number of sessions of substance use-specific counselling activities in individual or group formats. These sessions may be quite brief and sometimes offered on an outreach basis. | |

| Substance use community services | Moderate | This involves a scheduled course of 1- to 2-hour sessions of substance use-specific counselling in group sessions or an individual format. This category also includes opioid replacement services with or without a counselling component. |

| Intensive | This involves a structured schedule of substance use-specific counselling activities taking place over some days/evenings, or part days/evenings, of the week. This category may include the initial intensive phase of opiate replacement therapy. Programs are generally offered for a defined number of weeks while the client resides elsewhere. | |

| Supportive recovery | This involves accommodation and a range of lifestyle and psychosocial supports in an alcohol and drug-free setting but not including a highly structured schedule of treatment. | |

| Substance use residential services | Residential treatment | These services provide accommodation as well as structured, scheduled interventions and activities specifically designed to ameliorate substance use problems and/or moderate severity co-occurring disorders. |

| Complexity-enhanced treatment | These services provide accommodation within a health care setting with a high level of medical and psychiatric capability and which involve structured, scheduled programs of substance use treatment activities for clients with significant substance use problems, co-occurring medical/psychiatric disorders, or other complex needs. | |

| Internet-based (virtual) and mobile-based technologies | These innovations are emerging as critically important in the delivery of substance use services and supports and have been increasingly harnessed to distribute educational and health literacy materials as well as deliver a range of self-administered and therapist-assisted interventions. | |

| Other services and supports | Mutual aid groups | Supports available through groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous are widely recognized as a key component of substance use systems. |

| Housing | This involves accommodation that addresses the continuum of housing needs of people with substance use problems, and/or co-occurring disorders. Options vary from short-term low-threshold shelter to supervised supportive housing to longer term third-stage housing with access to more limited supports. | |

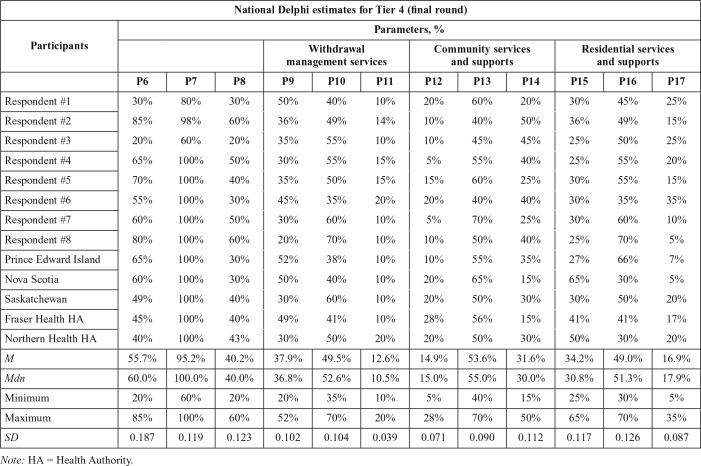

A Delphi process (Linstone & Turoff, 2002) was used to allocate the overall help-seeking population to the various service categories, with parameters p6–p17 referring to the proportions determined through this process to require each type of service. Parameters p18–p23 refer to transitions between service categories. A total of 30 participants made up nine expert panels with representation from clinicians (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, certificated addiction counselors); researchers (e.g., epidemiologists, health system analysts); and system planners or administrators (e.g., program managers, policy analysts, and information specialists). Participants came from 8 of the 13 provinces and territories in Canada, providing both rural and urban perspectives.

A three-round Delphi process with each of the nine panels yielded a consensus in each group on parameters p6–p17 (Table 2). For the national model, the median value was selected as the midpoint not influenced by extreme opinions. Parameters p18–p23 refer to transitions between service categories but were not estimated as they were seen by both the investigator team and Delphi participants to be too complex and dependent on regional, contextual factors for this type of national model building exercise based on expert opinion.

Table 2.

Results from the final round of National Delphi for Category 4 severity

| National Delphi estimates for Tier 4

(final round) | ||||||||||||

| Parameters, % |

||||||||||||

| Participants | Withdrawal management

services |

Community services and

supports |

Residential services and

supports |

|||||||||

| P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 | P13 | P14 | P15 | P16 | P17 | |

| Respondent #1 | 30% | 80% | 30% | 50% | 40% | 10% | 20% | 60% | 20% | 30% | 45% | 25% |

| Respondent #2 | 85% | 98% | 60% | 36% | 49% | 14% | 10% | 40% | 50% | 36% | 49% | 15% |

| Respondent #3 | 20% | 60% | 20% | 35% | 55% | 10% | 10% | 45% | 45% | 25% | 50% | 25% |

| Respondent #4 | 65% | 100% | 50% | 30% | 55% | 15% | 5% | 55% | 40% | 25% | 55% | 20% |

| Respondent #5 | 70% | 100% | 40% | 35% | 50% | 15% | 15% | 60% | 25% | 30% | 55% | 15% |

| Respondent #6 | 55% | 100% | 30% | 45% | 35% | 20% | 20% | 40% | 40% | 30% | 35% | 35% |

| Respondent #7 | 60% | 100% | 50% | 30% | 60% | 10% | 5% | 70% | 25% | 30% | 60% | 10% |

| Respondent #8 | 80% | 100% | 60% | 20% | 70% | 10% | 10% | 50% | 40% | 25% | 70% | 5% |

| Prince Edward Island | 65% | 100% | 30% | 52% | 38% | 10% | 10% | 55% | 35% | 27% | 66% | 7% |

| Nova Scotia | 60% | 100% | 30% | 50% | 40% | 10% | 20% | 65% | 15% | 65% | 30% | 5% |

| Saskatchewan | 49% | 100% | 40% | 30% | 60% | 10% | 20% | 50% | 30% | 30% | 50% | 20% |

| Fraser Health HA | 45% | 100% | 40% | 49% | 41% | 10% | 28% | 56% | 15% | 41% | 41% | 17% |

| Northern Health HA | 40% | 100% | 43% | 30% | 50% | 20% | 20% | 50% | 30% | 50% | 30% | 20% |

| M | 55.7% | 95.2% | 40.2% | 37.9% | 49.5% | 12.6% | 14.9% | 53.6% | 31.6% | 34.2% | 49.0% | 16.9% |

| Mdn | 60.0% | 100.0% | 40.0% | 36.8% | 52.6% | 10.5% | 15.0% | 55.0% | 30.0% | 30.8% | 51.3% | 17.9% |

| Minimum | 20% | 60% | 20% | 20% | 35% | 10% | 5% | 40% | 15% | 25% | 30% | 5% |

| Maximum | 85% | 100% | 60% | 52% | 70% | 20% | 28% | 70% | 50% | 65% | 70% | 35% |

| SD | 0.187 | 0.119 | 0.123 | 0.102 | 0.104 | 0.039 | 0.071 | 0.090 | 0.112 | 0.117 | 0.126 | 0.087 |

Note: HA = Health Authority.

Results

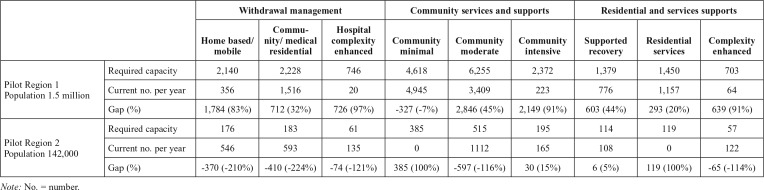

We pilot tested the model between 2011 and 2014. The 9 sites, covering 6 of the 10 provinces, included rural, urban, and coastal areas with populations from 140,000 to 1.5 million. Table 3 shows the results of the model projection and gap analysis for 2 of the pilot sites.

Table 3.

Results of gap analysis in two pilot sites

| Withdrawal management |

Community services and supports |

Residential and services

supports |

||||||||

| Home based/mobile | Community/medical residential | Hospital complexity enhanced | Community minimal | Community moderate | Community intensive | Supported recover)7 | Residential sendees | Complexity enhanced | ||

| Pilot Region 1 Population 1.5 million | Required capacity | 2,140 | 2,228 | 746 | 4,618 | 6,255 | 2,372 | 1,379 | 1,450 | 703 |

| Current no. per year | 356 | 1,516 | 20 | 4,945 | 3,409 | 223 | 776 | 1,157 | 64 | |

| Gap (%) | 1,784 (83%) | 712 (32%) | 726 (97%) | -327 (-7%) | 2,846 (45%) | 2,149 (91%) | 603 (44%) | 293 (20%) | 639 (91%) | |

| Pilot Region 2 Population 142,000 | Required capacity | 176 | 183 | 61 | 385 | 515 | 195 | 114 | 119 | 57 |

| Current no. per year | 546 | 593 | 135 | 0 | 1112 | 165 | 108 | 0 | 122 | |

| Gap (%) | -370 (-210%) | -410 (-224%) | -74 (-121%) | 385 (100%) | -597 (-116%) | 30 (15%) | 6 (5%) | 119 (100%) | -65 (-114%) | |

Note: No. = number.

Site 1. In this region, the results showed the largest gaps relative to required capacity for the most intensive services: for withdrawal management—medical detox; for community services and supports of treatment—day/evening treatment; and for residential services and supports—hospital inpatient. This reflected a trend across the majority of sites toward a shortage in the supply of the more intensive treatment options. The 1,784 / 2,140 or 83% treatment gap for home-based mobile withdrawal management was also interesting because this region had pioneered community withdrawal management for many years with considerable success in reducing emergency room visits. However, the data still reflected the need for more such community resources.

Shortly after the pilot work was completed, the respective provincial government announced that funding would be made available for a significant increase in residential treatment beds, based largely on community demand for this level of care. The results of the gap analysis were instrumental in determining the allocation of these beds to the region hosting the pilot work because they already had the largest share of such beds in the province. Enhanced education on the need for day treatment resources, to complement the residential bed allocation, was another result. The findings also helped solidify the perceived value of mobile/community withdrawal management, which had previously been determined to meet the needs of rural and indigenous communities.

Site 2. The results of the gap analysis for Site 2 were of considerable interest given the significant negative gap (i.e., over-utilization) that resulted for all categories of withdrawal management services, which was quickly flagged as a possible flaw in the model. On further investigation, the overuse of withdrawal management and the service gap for community residential treatment helped identify a treatment system continuity gap. Upon discharge from withdrawal management, people were not able to access residential treatment beds that operated as a closedcycle, single-gender model; this meant waiting upwards of 6 weeks for an appropriate space. A 10-bed residential treatment facility was opened in April 2014, supported in large part by the results of the gap analysis. The program was also converted to a continuous admission, mixed-gender model, which resulted in a significant bridge to clients in continuing treatment. This conversion was met with resistance initially; however, the evidence provided by the pilot work was considered instrumental in demonstrating the value of repurposing these beds and investing in additional programming.

Discussion

Aside from the utility of the identified service gaps, the process of working with the model meant consideration of new evidence-based service delivery models such as community mobile withdrawal management as an alternative to less cost-effective inpatient services, or intensive day/evening treatment as an alternative to community residential services. Further, regardless of the specifics of the gap analysis, the grounding of the analysis and planning process in the needs of the overall population was viewed as a new orientation for many stakeholders and a significant improvement on past practices. This is reminiscent of the various ways that evaluation results can be “used,” quite often to encourage a new perspective or value-orientation as opposed to direct “instrumental” use in decision-making (Shulha & Cousins, 1997).

The following are several lessons learned during the pilot work, organized according to challenges within the model itself and challenges with respect to its implementation.

Challenges within the needs-based planning model itself

The application of the planning model in the various pilot sites yielded interpretable information on system gaps or imbalances; this information was said to triangulate well with other local data and key informant opinion. Given this triangulation, few recommendations emerged that would change the specific parameters of the model, in particular the Delphi estimates. Broad support was also included for the approach to defining needs on the basis of a case-index measure, as opposed to strict diagnostic criteria, not unlike that used in other areas of planning in Canada (e.g., establishing the need for housing supports of varying intensity; Goering et al., 2011).

However, three important points for future consideration are the demand estimates for help-seeking (p2), the need to incorporate additional service categories, and a perceived need for a youth-focused model and a broader model for mental health services. With respect to the help-seeking estimates, we opted for estimates based on help-seeking as determined by population surveys, as opposed to setting an ideal target for penetration into the in-need population. An ideal target might be established, for example, by considering the need to, at a minimum, strike a balance between annual incidence rates and outcome, including natural recovery as well as treatment success and relapse/recidivism (see, for example, Brennan et al., 2019). The estimate of help-seeking derived from survey data, rather than a hypothetical help-seeking target, was chosen because of lack of data for the kind of simulation modeling required to generate an ideal target rate with confidence in the Canadian context.

Another challenge with respect to the help-seeking estimate was evident in the experience of some pilot sites, which led to the introduction and subsequent pilot testing of a range of help-seeking parameters in order to account for local contextual factors such as a distance to travel to services and available informatics concerning waiting times and out-of-region treatment. Allowing for such flexibility led to the identification of system gaps that better resonated with local stakeholders and that also set more realistic service delivery targets.

Challenges with respect to the delineation of the nine service categories in the model were identified. Notwithstanding general agreement with the definitions and applicability of the categories used in the model, there were notable omissions from the perspective of several stakeholders. Most notable were community needs for stabilization beds and other recovery support services that would serve as an intermediary step between withdrawal management and residential treatment; housing supports (Goering et al., 2011); harm reduction-related services such as needle exchange and safe consumption services (Jozaghi & Andresen, 2013); and Internet and mobile technology–based services (e.g., Molfenter et al., 2015). Several site participants noted the lack of attention to services for family members as well as the need for a broader focus on mental health services for more integrated systems planning (e.g., psychiatric inpatient services, crisis response, intensive case management [e.g., ACT/PACT teams; Goldner et al., 2016). Although participants were supportive of the decision to include placeholders for help-seeking from systematic screening efforts such as SBIRT, this aspect of the model was viewed as important for future enhancements as well as testing of scenarios to estimate the potential increase in required treatment capacity if SBIRT were to be implemented on a wider scale. Planning requirements for a youth-specific model were also highlighted, and a model subsequently developed for the province of Quebec (Tremblay et al., 2019) may be scalable to the national level. Although many of these enhancements are now under consideration in the next iteration of the planning model, the perceived omissions remind us of the importance of needs-based planning models to be continuously updated as new, evidence-based models of service delivery emerge in the literature.

Challenges with respect to model implementation

Challenges with the data source for population needs.

Relying on population survey data as the primary source of information for treatment needs has several advantages but also concomitant challenges from a needs assessment point of view (Dewit & Rush, 1996; Ritter et al., 2019b). In the Canadian context, a national survey with sufficient coverage of substance use, mental disorders, and chronic conditions that is required to create a comorbidity-based case index is conducted only periodically. In the present project, the 2002 Canadian Community Health Survey 1.2 was used, and no future survey is assured beyond the one replication in 2012. Aside from its periodicity and keeping data current, the national mental health survey does not include the full range of mental disorders; Axis II personality disorders being the most notable exclusion. Population surveys also are challenged to adequately estimate low frequency, but critically important, nonprescription opioid use disorder (Popova et al., 2009), a particularly noteworthy challenge identified in a number of pilot sites. Populations excluded from the survey sampling also presented significant challenges (e.g., people who are homeless or institutionalized at the time of the survey, and Indigenous people living on reserve). The exclusion of reserve-based Indigenous people was identified as a major challenge in several pilot regions given their significant representation in the population, high levels of substance use and related problems (First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2012), and their right to access off-reserve substance use and other health services.

Disconnected data collection systems.

Ritter et al. (2019b) note the challenges with disparate data collection systems capturing unduplicated service utilization data for purposes of gap analysis; challenges experienced in the majority of our pilot sites. This challenge was exacerbated in treatment systems that have responded to the call for closer integration of mental health and substance use services (Rush & Nadeau, 2011) and is likely to become even more of a challenge given the international trend toward increased collaboration with primary care (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Thus, although a population-based approach calls for such a broad multi-sectoral response (Babor et al., 2008), this yields a corresponding problem in data linkage for gap analysis and planning purposes. Interestingly, the senior administrators in the pilot sites expressing a desire for a needs-based planning model that projects required capacity for mental health services also acknowledged the current state of nonlinkable client information systems across mental health and substance use services.

Mismatch between ecological catchment areas and planning zones.

An underlying assumption in the planning model is that the commissioning of services is typically undertaken on a geographic basis. However, some residents of the planning region may need, or choose, to travel outside of their area to access appropriate treatment services. Residential facilities, in particular, have large catchment areas that may span several local planning regions. In addition, having correctional facilities or seasonal or resource-based employment opportunities in a region may cause an influx of clients into local services who are not native to the region, and thereby not reflected in local health survey data.

Consideration of for-profit treatment services.

One significant challenge applicable to several of the pilot sites was the presence of independent or for-profit treatment services, particularly for residential treatment. These services are not always bound by the same minimum standards as publicly funded services, and there is often no mandatory mechanism in place to accurately assess service utilization at these independent facilities for inclusion in a gap analysis. Their exclusion can lead planners to overestimate the treatment gap. In Canada’s largely publicly funded health care system, varied opinions were noted as to whether our quantitative gap analysis should include or exclude that part of the treatment gap filled by private providers.

Need for support in implementation.

An important realization during and after pilot testing concerned the level of support required for implementation of the model. This included support for interpretation of the tiered severity categories, considerations for flexibility in the help-seeking parameters, and assistance estimating current service utilization and interpreting the gap analysis. This remains a concern going forward and reflects the need for an implementation science framework (Fixsen et al., 2005) that considers this needs-based planning approach as an evidence-informed practice for system design that requires thoughtful knowledge translation. Implementation may require a designated implementation coaching role that also includes up-to-date knowledge of current evidence-informed practices at the intervention levels to ensure that system planning is not divorced from the ensuing specific interventions in which prospective clients will ultimately be engaged.

Conclusion

There is no one simple formula to assist with treatment system planning but rather a collection of tools that can be used together to inform treatment gaps and resource allocation. That being said, evaluation feedback from stakeholders indicated that they are highly motivated to use a needs-based planning model as was developed and tested in this project but also cautioning, however, that it be used as one piece of a larger planning process and not solely as a stand-alone “formula” to determine quantitative service gaps. System planners should also use other indicators of need (e.g., social indicators, key informant opinion, wait lists) and regional indicators (e.g., accessibility to services based on distance and travel time). Further, the model should be applied with the support of people trained in community needs assessment to ensure the results are being interpreted correctly and with the larger community and sociopolitical context in mind.

It is important to reiterate the challenges in modeling treatment systems that, in the end, must speak to complex environments, nonlinear individual treatment trajectories, and reverse directionality (Ritter et al., 2019b). The body of work in this area of research and development speaks to the need for much more sophisticated simulation modeling than can be undertaken at present in Canada given available data and information systems. This, however, should be the longer-term goal of this foundational work in the Canadian context. It is also important to note that less complex models may be a better starting place for low-income countries given known challenges with mental health and substance use information systems and infrastructure in these jurisdictions (Upadhaya et al., 2016). The process of development and key features of this Canadian model can no doubt be adapted to other jurisdictions and contexts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank other members of the project—Chantal Fougere, Renée Behrooz, Wendi Perez, Julia Fineczko, Anna Marie Danielson, Eric Mintz, and the 15 members of the project Advisory Committee—for their support bringing this phase of the work to fruition. We would also like to thank representatives of the various project pilot sites across Canada.

Footnotes

This work was supported with funding from the Health Canada Drug Treatment Funding Program. Support to CAMH for salary of scientists and infrastructure was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P., Laurant M., Kaner E., Wensing M., Grol R. Engaging general practitioners in the management of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption: Results of a meta-analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:191–199. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.191. doi:10.15288/jsa.2004.65.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T. F., Stenius K., Romelsjö A. Alcohol and drug treatment systems in public health perspective: mediators and moderators of population effects. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17(Supplement 1):S50–S59. doi: 10.1002/mpr.249. doi:10.1002/mpr.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S. F., Best D., Manning V., Savic M., Lubman D. I., Rush B. A tiered model of substance use severity and life complexity: Potential for application to needs-based planning. Substance Abuse. 2016;37:526–533. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1143907. doi:10.1080/08897077.2016.1143907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijl R. V., de Graaf R., Hiripi E., Kessler R. C., Kohn R., Offord D. R., Wittchen H.-U. The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Affairs. 2003;22:122–133. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.122. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette-Martin N., Tremblay J., Ferland F., Rush B., Garceau P., Danielson A.-M. Co-location of addiction liaison nurses in three Quebec City emergency departments: Portrait of services, patients, and treatment trajectories. Canadian Journal of Addiction. 2016;7:34–40. Retrieved from https://www.csam-smca.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/CJA-vol7-no-3-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan A., Hill-McManus D., Stone T., Buykx P., Ally A., Pryce R. E., Drummond C. Modelling the potential impact of changing access rates to specialist treatment for alcohol dependence for local authorities in England – the Specialist Treatment for Alcohol Model (STreAM) Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2019;(Supplement 18):96–109. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.96. doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J. A., Breslin F. C. Only one in three people with alcohol abuse or dependence ever seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:221–223. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00077-7. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Stinson F. S., Chou P. S., Huang B., Ruan W. J. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002. Addiction. 2005;100:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Glantz M., Evans-Lacko S., Sadikova E., Sampson N., Thornicroft G., Kessler R. C. the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Surveys collaborators. Estimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: An analysis of data from the World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:299–307. doi: 10.1002/wps.20457. doi:10.1002/wps.20457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewit D. J., Rush B. Assessing the need for substance abuse services: A critical review of needs assessment models. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1996;19:41–64. doi:10.1016/0149-7189(95)00039-9. [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G., Degutis L. C. Integrating Project ASSERT: A screening, intervention, and referral to treatment program for unhealthy alcohol and drug use into an urban emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17:903–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00824.x. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne J., Kimergård A., Brown J., Beard E., Buykx P., Michie S., Drummond C. Attempts to reduce alcohol intake and treatment needs among people with probable alcohol dependence in England: A general population survey. Addiction. 2018;113:1430–1438. doi: 10.1111/add.14221. doi:10.1111/add.14221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce R., Schuler M. S. Rates of past-year alcohol treatment across two time metrics and differences by alcohol use disorder severity and mental health comorbidities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;166:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.010. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Information Governance Centre. Ottawa, Ontario: Author; 2012. First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen D. L., Naoom S. F., Blase K. A., Friedman R. M., Wallace F. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida; 2005. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Retrieved from http://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/NIRNMonographFull-01-2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ford W. E. Alcoholism and drug abuse service forecasting models: A comparative discussion. International Journal of the Addictions. 1985;20:233–252. doi: 10.3109/10826088509044908. doi:10.3109/10826088509044908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastfriend D. R., Mee-Lee D. The ASAM patient placement criteria: Context, concepts, and continuing development. In: Gastfriend D. R., editor. Addiction treatment matching. Research Foundations of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Criteria (pp. 1–8) New York, NY: The Haworth Medical Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goering P. N., Streiner D. L., Adair C., Aubry T., Barker J., Distasio J., Zabkiewicz D. M. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: A pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner E. M., Blisker D., Jenkins E. Toronto, Ontario: Scholar’s Press; 2016. A concise guide to mental health in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Gravel R., Béland Y. The Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:573–579. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001002. doi:10.1177/070674370505001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothues J. M., Bischof G., Reinhardt S., Meyer C., John U., Rumpf H. J. Differences in help seeking rates after brief intervention for alcohol use disorders in general practice patients with and without comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17(Supplement 1):S74–S77. doi: 10.1002/mpr.253. doi:10.1002/mpr.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. G., Diminic S., Burgess P. M., Carstensen G., Stewart G., Pirkis J., Whiteford H. A. Understanding service demand for mental health among Australians aged 16 to 64 years according to their possible need for treatment. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;48:838–851. doi: 10.1177/0004867414531459. doi:10.1177/0004867414531459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S., Andrews G., Hall W. Australia’s mental health: An overview of the general population survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;34:197–205. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00686.x. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. Division of Mental Health and Behavioral Medicine.Broadening the base of treatment for alcohol problems. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi F., Wittchen H. U., Hölting C., Höfler M., Pfister H., Müller N., Lieb R. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: Results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS) Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:597–611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001399. doi:10.1017/S0033291703001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M., Jackson R., Guillaume L., Meier P., Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Journal of Public Health. 2010;33:412–421. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq095. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozaghi E., Andresen M. M. Should North America’s first and only supervised injection facility (InSite) be expanded in British Columbia, Canada? Harm Reduction Journal. 2013;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-1. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann H., Hunt G. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Drug treatment systems in an international perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann H., Takala J., Hunt G. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1992. Cure, care, or control. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone H. A., Turoff M. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; Advanced Book Program: 2002. The Delphi method: Techniques and applications (Vol. 18) [Google Scholar]

- Madras B. K., Compton W. M., Avula D., Stegbauer T., Stein J. B., Clark H. W. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: Comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;99:280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Lewis D. C., O’Brien C. P., Kleber H. D. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. doi:10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows G., Harvey C., Fossey E., Burgess P. Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: Development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s001270050260. doi:10.1007/s001270050260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Is the prevalence of mental disorders a good measure of the need for services? Health Affairs. 2003;22:8–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.8. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Use of specialty substance abuse and mental health services in adults with substance use disorders in the community. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Unmet need for treatment of major depression in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:297–305. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molfenter T., Boyle M., Holloway D., Zwick J. Trends in telemedicine use in addiction treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2015;10:14. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0035-4. doi:10.1186/s13722-015-0035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence (Great Britain) Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society; 2011. Alcohol-use disorders: Diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence (NICE Clinical Guidelines No. 115) Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0042164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P., Aalto M., Bendtsen P., Seppä K. Effectiveness of strategies to implement brief alcohol intervention in primary healthcare. A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2006;24:5–15. doi: 10.1080/02813430500475282. doi:10.1080/02813430500475282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova S., Patra J., Mohapatra S., Fischer B., Rehm J. How many people in Canada use prescription opioids non-medically in general and street drug using populations? Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique. 2009;100:104–108. doi: 10.1007/BF03405516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N. J., Cvetkovski S., Jorm A. F., Lubman D. I. Help-seeking for substance use, anxiety and affective disorders among young people: Results from the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:729–735. doi: 10.3109/00048671003705458. doi:10.3109/00048671003705458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A., Gomez M., Chalmers J. Measuring unmet demand for alcohol and other treatment: The application of an Australian population-based planning model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2019a;(Supplement 18):42–50. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.42. doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A., Mellor R., Chalmers J., Sutherland M., Lancaster K. Key considerations in planning for substance use treatment: Estimating treatment need and demand. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2019b;(Supplement 18):22–30. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.22. doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche A. M., Freeman T. Brief interventions: Good in theory but weak in practice. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2004;23:11–18. doi: 10.1080/09595230410001645510. doi:10.1080/09595230410001645510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R., Babor T., Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. The Lancet. 2005;365:519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. A systems approach to estimating the required capacity of alcohol treatment services. British Journal of Addiction. 1990;85:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. Tiered frameworks for planning substance use service delivery systems: Origins and key principles. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;27:617–636. doi:10.1177/145507251002700607. [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. R., Nadeau L. On the integration of mental health and substance use services and systems. In: Cooper D. B., editor. Responding in mental health—Substance use (pp. 148–175) Oxford, England: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. R., Tremblay J., Babor T. Needs-based planning for substance use treatment systems: The new generation of principles, methods and models. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement 18. 2019a:5–8. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.5. doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B., Tremblay J., Fougere C., Behrooz R. C., Perez W., Fineczko J. Toronto, Ontario: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2014. Development of a needs-based planning model for substance use services and supports in Canada: Final report 2010–2014. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. R., Urbanoski K.2019bSeven core principles of substance use treatment system design to aid in identifying strengths, gaps and required enhancement Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , Supplement189–21.doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulha L. M., Cousins J. B. Evaluation use: Theory, research, and practice since 1986. American Journal of Evaluation. 1997;18:195–208. doi:10.1177/109821409701800302. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Ellingstad T. P., Sobell M. B. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: Methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95:749–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Author; 2013. Systems-level implementation of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 33. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4741. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay J., Bertrand K., Blanchette-Martin N., Rush B., Savard A.-C., L’Espérance N., Genois R.2019Estimation of need for addiction services: A youth model Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs , Supplement1864–75.doi:10.15288/jsads.2019.s18.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Vienna, Austria: Author; 2016. International standards in the treatment of drug use disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhaya N., Jordans M. J. D., Abdulmalik J., Ahuja S., Alem A., Hanlon C., Gureje O. Information systems for mental health in six low and middle income countries: Cross country situation analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2016;10:60. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0094-2. doi:10.1186/s13033-016-0094-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanoski K. A., Rush B. R., Wild T. C., Bassani D. G., Castel S. Use of mental health care services by Canadians with co-occurring substance dependence and mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:962–969. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.962. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Author; 2016. Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Retrieved from https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. S., Lane M., Olfson M., Pincus H. A., Wells K. B., Kessler R. C. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. C., Johnson M. L., Lapham G. T., Caldeiro R. M., Chew L., Fletcher G. S. Bradley K. A. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:206–214. doi: 10.1037/a0022102. doi:10.1037/a0022102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2017. ATLAS on substance use 2017: Resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. T., Kouzis A. C., Schlenger W. E. Substance use, dependence, and service utilization among the US uninsured nonelderly population. American Journal of Public Health. 2003a;93:2079–2085. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2079. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. T., Ringwalt C. L. Alcohol dependence and use of treatment services among women in the community. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1790–1797. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.10.1790. doi:10.1176/ajp.161.10.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. T., Ringwalt C. L., Williams C. E. Use of substance abuse treatment services by persons with mental health and substance use problems. Psychiatric Services. 2003b;54:363–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.363. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]