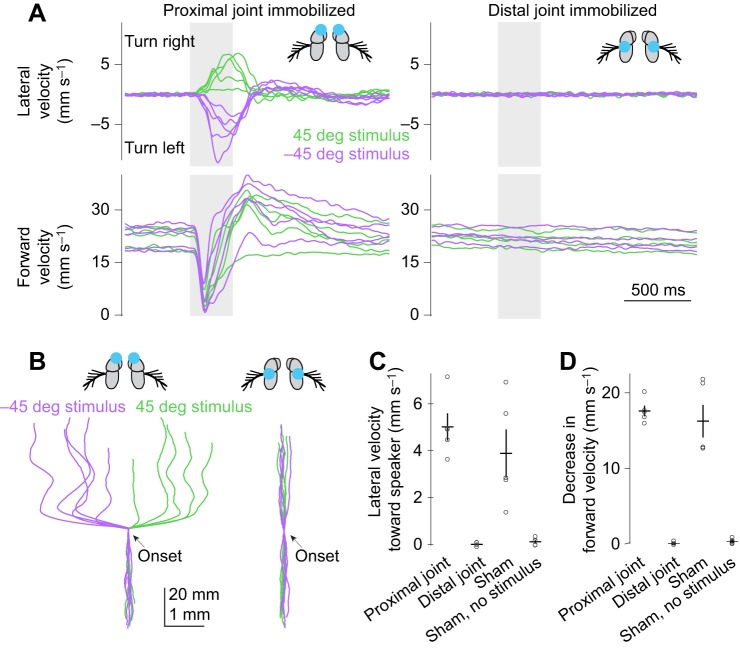

Fig. 4.

Phonotaxis requires vibration of the distal antennal segment. (A) Left: immobilizing the proximal antennal joint (the a2–a1 joint) does not eliminate phonotaxis or acoustic startle. Right: immobilizing the distal antennal joint (the a3–a2 joint) completely eliminates both behaviors. Speakers were positioned at 45 and −45 deg. In each plot, each trace shows data for one fly (left: n=5 flies; right: n=4 flies) averaged across trials. Blue dots in schematics represent glue drops. With regard to baseline forward velocity, note that both groups of manipulated flies are similar to unmanipulated flies (Fig. 2D). (B) Trial-averaged paths (x and y displacements) for each fly. (C) Lateral velocity toward the speaker, averaging data from the two speaker positions. Lateral velocity is significantly different when the distal joint is immobilized compared with either immobilizing the proximal joint or ‘sham-glued’ controls (P<0.05 in both cases, Games–Howell test; sham data are a subset of the data from Figs 2, 3). When the proximal joint is immobilized, lateral velocity is not significantly different from that of ‘sham-glued’ controls. Each dot is one fly. Lines are means±s.e.m. across flies. (D) Decrease in forward velocity, averaging data from the two speaker positions. Decrease in forward velocity is significantly different when the distal joint is immobilized compared with either immobilizing the proximal joint or ‘sham-glued’ controls (P<0.05 in both cases, Games–Howell test; sham data are a subset of the data from Figs 2, 3). When the proximal joint is immobilized, the decrease in forward velocity is not significantly different from that of ‘sham-glued’ controls (P>0.05, Games−Howell test).