Abstract

PURPOSE:

Communication skills are essential for medical practice throughout the life of a doctor. Traditional undergraduate medical teaching in pediatrics focuses on teaching students with theoretical and practical knowledge of diseases, their diagnosis, and treatment modalities. This study was done to use role play as a tool to teach basic communication skills to the final-year undergraduate students in pediatrics and to assess perceptions of students and faculty for using role play to teach counseling and communication skills in pediatrics.

METHODS:

It was an observational, questionnaire-based study conducted in the Department of Pediatrics on the final-year medical undergraduates. Two modules for role play on common pediatric topics were designed and role play was conducted. At the end of the session, student and faculty feedback were taken by a prevalidated questionnaire with both close (using the 5-point Likert scale) and open-ended questions. In pre- and post-role play sessions, communication skills assessment scoring was done. Statistical evaluation of the collected data was then carried out using SPSS 22.

RESULTS:

A total of 98 final-year students participated in this study. Role play was found to be the most preferred tool (33%) for teaching communication skills to the students. Majority of the students (88.78%) and faculty (91.67%) felt that role play helped in teaching communicating skills. Comparison of pre- and post-role play scores on communication skills showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

Role play can be used as an effective tool to teach communication skills to undergraduate medical students in pediatrics.

Keywords: Communication skills, medical students, pediatrics, perceptions, role play

Introduction

Communication skills are essential for medical practice throughout the life of a doctor. Traditional undergraduate medical teaching in pediatrics focuses on teaching students with theoretical and practical knowledge of diseases, their diagnosis, and treatment modalities. However, it does not address communication skills which are one of the essential elements of dealing with patients and the role of a future Indian Medical Graduate (IMG).[1,2]

Communication skills of doctors have a significant impact on patient care and finally correlates with improved health-care outcomes in the future.[3] Better communication between doctor and patient builds confidence, improves compliance, and also leads to a reduction of medical litigations due to perceived medical negligence. Good communication skills and counseling techniques need to be taught to medical undergraduates to make them doctors of greater clinical competence.[4]

Doctor–patient communication is the backbone and the mainstay of patient care. Communication skills comprise of first contact patient interviews, probing for associated and additional problems, explaining about the illness, its complications, treatment options, and advising follow-up. It is also necessary for explaining risks to the patient, counseling in case of bereavement or mishap, providing information about a surgical procedure and its complications, taking informed consent, and many other areas of patient care.

It is “the need of the hour” to train medical professionals in communication skills because it has become an ignored aspect of clinical medicine.[5] The medical system all over the world has witnessed an increase in the incidences of conflict between doctors and patients or their attendants. There has been an increase in both the number of lawsuits against doctors as well as the mass level agitations by doctors. These incidents are not only appalling but also deplorable and shameful for the noble medical profession. There is enough evidence in literature to suggest that poor communication between doctors and patients is an important attributing factor.[6,7]

Didactic lectures are not able to teach communication skills to students. Role plays in the safe environment of classrooms help students experience and understand both the doctor's as well as patient's perspectives and also learn the complexity of the doctor–patient interview. Role play helps students learn to empathize with patients and also allow students to have fun while learning. The present study was undertaken to determine the perceptions of the final-year medical students and faculty in an Indian medical college about the use of role play in teaching communication skills to undergraduate medical students.

The goal of the study was to make IMG fulfill the role of a communicator by learning good communication skills besides having cognitive and psychomotor skills. The aim was to teach good communication and counseling skills to undergraduate medical students so that they become doctors of better clinical competence.

The objective of the study was to use role play as a tool to teach basic communication and counseling skills to the final-year undergraduate students in pediatrics who would very soon be dealing with real patients during internship. The study was also done to assess perceptions of students and faculty for using role play to teach counseling and communication skills in pediatrics.

Methods

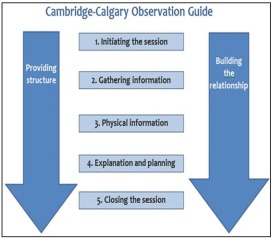

The study was an observational, questionnaire-based study and was conducted in the Department of Pediatrics.First, ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IRB No. 39/2017 dt 06 Nov, 2017 of Base Hospital, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi, India). After sensitizing all the faculty of the department, two modules were designed and finalized by the departmental subject experts keeping in mind the learning objectives. Each module consisted of one commonly encountered medical problem in pediatrics. The topics chosen were “febrile convulsions” and “acute gastroenteritis.” The basic structure and objectives of the module for the role play was to deal with common and important case scenarios, teach communication skills to the students in the form of taking a brief history and counselling mother about the nature of the illness, home management (identifying danger signs and giving medications), and prognosis of the condition. The “Calgary–Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview”[8,9] and “Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist” (adapted)[10] was considered as the reference for preparing the module for the students [Annexure 1 and 2].

Final-year students were taken for the study as in a few months’ time, they would be starting their internship and would be directly dealing with the patients in the outpatient departments as well as the patients admitted in the wards. These medical students of the final year have already acquired a reasonable amount of knowledge and psychomotor skills in all clinical specialties including pediatrics. This would have been the right and most crucial time to intervene and teach them communication skills to deal with the patients in a well-structured method as outlined in Calgary–Cambridge Communication Skills Guide.

Student volunteers of the final-year MBBS (8th term) participated in the role play sessions. Written informed consent was obtained from student volunteers. For each role play, four students were chosen. One week in advance, the role player team was given the module for preparation of the role play. Lecture on the same topic was taken at this time. Two faculties were assigned to each role play team and they guided the students in the conduct of the role play.

The script of role play was in Hindi and the actors used their own properties. Remaining students of the batch became observers. Each group was allocated 15–20 min to present their role play. The faculty acted as facilitators for the role play team. At the end of the role play, there was a debriefing session stressing on the communication skills as formulated in the module. One week later, the second role play was done similarly followed by the debriefing session. Thereafter, the students and the faculty completed a questionnaire.

The questionnaires contained both close-ended (using a 5-point Likert scale as a response scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree)[11] and open-ended questions to elicit their perceptions regarding the use of role play in pediatrics as a teaching method for communication skills [Annexure 3 and 4]

The data were analyzed on IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Cronbach's alpha coefficient test was used to assess the reliability of the questionnaire collected from students. The value of Cronbach's alpha coefficient test was 0.78, thus representing that the questionnaire was good in content. The results were obtained in the form of frequencies and percentages.

Pre role play communication skills score based on “Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist” (collected during the 7th-term end practical examination) were compared with 8th-term ward leaving practical examinations scores which were held after the role play examinations. The paired t-test was applied to compare these scores and P < 0.001 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

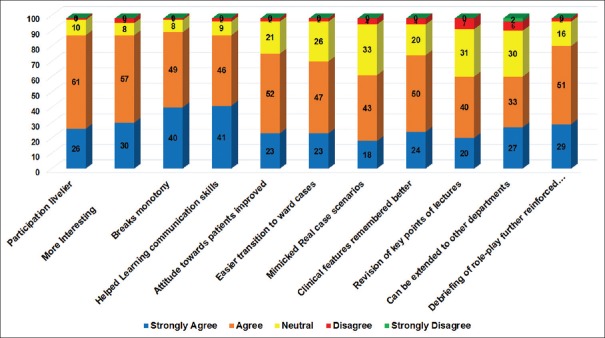

A total of 104 final-year (8th term) MBBS students participated in curriculum innovation project of role play. Only 98 of them submitted the filled questionnaires. Twelve faculties (including the postgraduate residents) were present for the role play and all of them filled the feedback questionnaire. The results showed that students preferred role play (33%), case-based learning (29%), tutorials (16%), small group discussions (12%), and lectures (10%) as the most preferred instructional tool to teach communication skills [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Instructional tool preferred by students

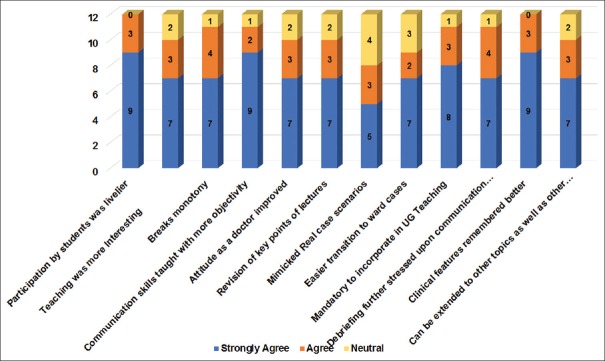

The perceptions of the students about the roleplay are as shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. About 88.78% agreed or strongly agreed that role play helped in learning communication skills, 76.53% felt that their attitude toward patients improved, and 71.43% of students felt that it would help them in easier transition toward cases. Role play was found to be more interesting and participation was found to be livelier by 88.78% of students. 90.82% of students found that it broke the monotony of learning.

Table 1.

Perception of students about using role play in teaching communication skills

| Questions | Strongly agree (n) | Agree (n) | Total % (SA + A) | Neutral (n) | Disagree (n) | Strongly disagree (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation livelier | 26 | 61 | 88.78 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 98 |

| More Interesting | 30 | 57 | 88.78 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 98 |

| Breaks monotony | 40 | 49 | 90.82 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 98 |

| Helped learning communication skills | 41 | 46 | 88.78 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

| Attitude toward patients improved | 23 | 52 | 76.53 | 21 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

| Easier transition to ward cases | 23 | 47 | 71.43 | 26 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

| Mimicked real case scenarios | 18 | 43 | 62.24 | 33 | 4 | 0 | 98 |

| Clinical features remembered better | 24 | 50 | 75.51 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 98 |

| Revision of key points of lectures | 20 | 40 | 61.22 | 31 | 7 | 0 | 98 |

| Can be extended to other departments | 27 | 33 | 61.22 | 30 | 6 | 2 | 98 |

| Debriefing of role play further reinforced communication skills | 29 | 51 | 81.63 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 98 |

n=Number of students, SA=Strongly agree, A=Agree

Figure 2.

Perception of students about using role play in teaching communication skills

Nearly 75.51% of students felt that role play helped them in remembering clinical features better, 61.22% students felt that it also helped in revision of key points of lectures, and 61.22% felt that it could be extended to other departments to teach communication and counseling skills. 81.63% of students felt that debriefing further helped in reinforcing communication skills.

Feedback from students for the open-ended questions

“It was very beneficial and I think it is a great innovative idea.”

“I wish other departments would also do role plays to get a flavor of how they communicate about diseases.”

“I think it would be even better to witness a real session.”

“Knowing it is fake made me feel a bit awkward at times.”

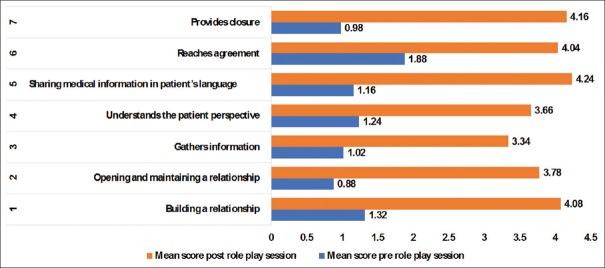

The perceptions of faculty about using role play in teaching communication skills are as shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. About 91.67% of faculty agreed or strongly agreed that role play helped teaching communication skills with more objectivity and 83.33% of faculty felt that the attitude of students toward the patients improved. 100% of faculty felt that role play made participation of students livelier and 83.33% faculty felt that teaching was made more interesting. 91.67% students felt that monotony in the classroom was broken.

Table 2.

Perception of teachers about using role play in teaching communication skills

| Questions | Strongly agree (n) | Agree (n) | Total % (SA + A) | Neutral (n) | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation by students was livelier | 9 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 12 |

| Teaching was more interesting | 7 | 3 | 83.33 | 2 | 12 |

| Breaks monotony | 7 | 4 | 91.67 | 1 | 12 |

| Communication skills taught with more objectivity | 9 | 2 | 91.67 | 1 | 12 |

| Attitude as a doctor improved | 7 | 3 | 83.33 | 2 | 12 |

| Revision of key points of lectures | 7 | 3 | 83.33 | 2 | 12 |

| Mimicked real case scenarios | 5 | 3 | 66.67 | 4 | 12 |

| Easier transition to ward cases | 7 | 2 | 75.0 | 3 | 12 |

| Mandatory to incorporate in UG teaching | 8 | 3 | 91.67 | 1 | 12 |

| Debriefing further stressed upon communication skills | 7 | 4 | 91.67 | 1 | 12 |

| Clinical features remembered better | 9 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 12 |

| Can be extended to other topics as well as other departments | 7 | 3 | 83.33 | 2 | 12 |

n=Number of faculty, SA=Strongly agree

Figure 3.

Perception of teachers about using role play in teaching communication skills

About 83.33% faculty felt that it would help in easy revision of key points of lectures, 66.67% faculty felt that role play mimicked real case scenarios, 75% of faculty felt that it would help in easier transition toward cases, and 100% faculty felt that this would help in remembering clinical features better. 91.67% faculty felt that role play can be extended to other departments to teach communication skills and it should be mandatory to incorporate in undergraduate teaching. 83.33% faculty felt that can be extended to other topics as well as to other departments.

Feedback from the faculty for the open-ended questions

“Faculty crunch and the existing faculty being busy with nonacademic/administrative jobs, where is the time to teach the students communication skills.”

“First, the faculty should be sensitized toward correct ways of teaching communication skills as most of us have learned it by chance from our teachers and seniors.”

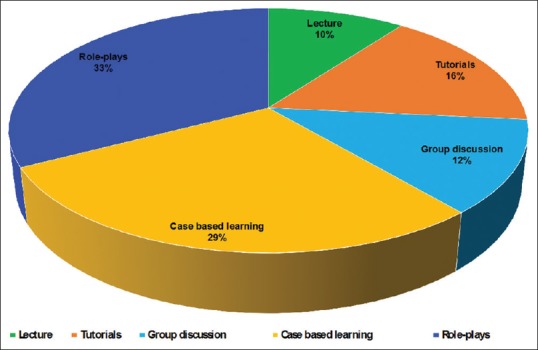

Comparisons of scores as per Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist before and after sensitization to role plays showed statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001) for all the points on the checklist [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Comparisons of scores as per Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist before and after sensitization to role plays

Discussion

Communication and counseling form a vital aspect of every doctor–patient interaction. Clinical practice requires a delicate synergy of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Our present medical curriculum does not address learning of attitudes and communication skills. Medical students usually end up learning the affective domain from either their teachers or their seniors (a hidden curriculum) and the process of learning is left to chance.

Role play is a powerful tool to make students learn communication skills in dealing with realistic clinical situations which require counseling or communication. Role play in a simulated scenario gives students a chance to develop their affective domain and also the opportunity for feedback and correction of their errors. Good communication skills can be taught to undergraduate through role play.[12]

Role plays were identified as the most effective method of teaching by a significantly greater number of students in other studies also.[13,14] Majority of students in our study felt that the role play helped them learn the correct attitudes required of a doctor to treat his patients. They felt that the role play could be an effective means for teaching communication skills. Perception of the students regarding role play in teaching communication skills was like in other studies.[13,14]

Manzoor et al. recommended that by engaging students in role plays, the components of both cognitive as well as the affective domain of medical education can be delivered.[15] In addition, role play offers the advantages of fostering affective skill development and empathy toward patients. He says it thus warrants inclusion in the medical curriculum. Another study also found that students had positive perceptions about role playing because it simulated life experience into the classroom or training session.[16]

In another study, it was found that besides role play being used as an effective training tool for teaching communication skills, it also increased the clinical knowledge of the students.[17] In our study also, a majority of the students felt that role play mimicked real cases and would facilitate the transition from classroom to the wards. During the role play, students are in a realistic yet nonthreatening environment in the classroom. They get an opportunity to practice affective skills as well as clinical skills without harming real patients.

Majority of our students had a positive perception of role play and felt that it could be adopted by other departments for training undergraduate students. This study differed from those of Stevenson and Sander[18] where the majority of the students had a negative perception about role play. The students felt the role play was very lively and encouraged active participation because of well-structured modules of common pediatric cases. The majority of our students felt that the debriefing session with group discussion and feedback helped them learn more from the role play.

The reasons for the overall positive perception of role play could be because an adequate time for preparation for the role play was given, involved all students either as role player or observer and defined ground rules very well. Debriefing, feedback, and reflection were done well and a sense of humor was also maintained to keep the students active, engaged, and entertained.[19] The reason for the overall positive perception of role play by our students could be because we used the guidelines of Nestel and Tierney for maximizing benefits of role play.[19] These guidelines were similar to those used in Joyner and Young's tips for successful role play.[20]

Comparison of test scores before and after the role play showed statistically significant improvement in scores for communication skills because we attempted to follow “Calgary–Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview” and “Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist” for successful role play.

The system of multiple re-enforcements consisting of lectures followed by role play and then PowerPoint slides summarizing key features presented in the role play could be the reason for perceived better knowledge and learning also. The open-ended questions of the facilitator prompted students for reflection and subsequent discussion and ensured the active involvement of the students in the learning process. The whole process of role play was based on principles of adult learning identified by Knowles et al., such as “the need to know, readiness to learn, and orientation/problem centeredness,”[21] which could explain why our students too perceived the role play positively.

The outcome of the study was that role play sessions had a positive impact in improving communication skills in undergraduate students. This study offers a realistic basis for the use of role play in undergraduate pediatric students for the acquisition of communication skills and would go a big way in shaping doctors of tomorrow for their future clinical practice.

The feedback from both students and faculty was so overwhelming that it is time to seriously consider incorporation of role play in the current medical curriculum to foster learning attitude and communication skills.

Limitations

Only two topics were taken up for role play. There could have been an element of response bias as the student knows the researcher and consciously, or subconsciously, gives the response that they think that the interviewer wants to hear. Only quantitative data of a structured questionnaire of the study were analyzed. Even though a few open-ended questions to analyze the qualitative aspects regarding students’ perceptions has been incorporated, it has not been explored at depth. A focused group discussion of both faculty and students’ perspectives about the sessions would have added significant information too.

The effects of counseling skills training can also be tested in real patient encounters in the clinical setting using assessment methods such as mini-clinical evaluation exercise or objective structured clinical examination. The long-term impact of role play sessions in bringing around behavioral changes may be further investigated.

Conclusion

Majority of the students and faculty felt that role play can be used as an effective tool to improve the communication skills of undergraduate students. Besides the communication skills, knowledge was enhanced and would make dealing with real patients an easy transition. This would help in producing a competent IMG who would be a physician of the first contact with good communication skills. It can be very well incorporated in the undergraduate curriculum. Extra efforts and a wise planning from faculty can make a change in the attitude and communication skills in the doctors of tomorrow.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was a part of “Advance Course in Medical Education” and I would acknowledge the guidance of Dr. Tejinder Singh and Dr. Dinesh Badyal throughout the study. I am highly grateful to the faculty and staff of the Department of Paediatrics of Army College of Medical Sciences for providing all the support for this study.

Annexure 1

Annexure 2

Kalamazoo Essential Elements Communication Checklist (adapted for Memorial Medical School)

Student's Name:

Facilitator's Name:

Date of Session:

How well does the learner do the following:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| A. Builds a Relationship (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Greets and shows interest in patient as a person

Uses words that show care and concern throughout the interview

Uses tone, pace, eye contact, and posture that show care and concern

Responds explicitly to patient's statements about ideas and feelings

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| B. Opens the Discussion (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Allows patient to complete opening statement without interruption

Asks “Is there anything else?” to elicit full set of concerns

Explains and/or negotiates an agenda for the visit

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| C. Gathers Information (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Begins with patient’s story using open-ended questions (e.g.“tell me about…”)

Clarifies details as necessary with more specific or “yes/no” questions

Summarizes and gives patient opportunity to correct or add information

Transitions effectively to additional questions

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| D. Understands the Patient’s Perspective (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Asks about life events, circumstances, other people that might affect health

Elicits patient’s beliefs, concerns, and expectations about illness and treatment

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| E. Shares Information (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Assesses patient’s understanding of problem and desire for more information

Explains using words that patient can understand

Asks if patient has any questions

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| F. Reaches Agreement (if new/changed plan) (includes the following): □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Includes patient in choices and decisions to the extent s/he desires

Checks for mutual understanding of diagnostic and/or treatment plans

Asks about patients ability to follow diagnostic and/or treatment plans

Identifies additional resources as appropriate

Comments:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Poor | Fair | Good | V. Good | Excellent | |

| G. Provides Closure (includes the following): | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Asks if patient has questions, concerns or other issues

Summarizes

Clarifies follow-up or contact arrangements

Acknowledges patient and closes interview

Comments:

Adapted from Essential Elements: The Communication Checklist,

©Bayer-Fetzer Group on Physician-Patient Communication in Medical Education, May 2001, and from: The Bayer-Fetzer Group on Physician-Patient Communication in Medical Education. Essential Elements of Communication in Medical Encounters: The Kalamazoo Consensus Statement. Academic Medicine 2001; 76:390-393.

Annexure 3

Annexure 3.

Role play questionnaire for students

| 1 | Name (optional) | |||||

| 2 | Role | Observer | Role Player | |||

| 3 | Teaching tool preference | Lecture | Tutorials | Group discussion | Case-based learning | Role play |

| 4 | Use of role play in learning communication skills in pediatrics | |||||

| 5 | Variables | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| 6 | Participation livelier | |||||

| 7 | More interesting | |||||

| 8 | Breaks monotony | |||||

| 9 | Helped Learning communication skills | |||||

| 10 | Attitude toward patients improved | |||||

| 11 | Easier transition to ward cases | |||||

| 12 | Mimicked real case scenarios | |||||

| 13 | Clinical features remembered better | |||||

| 14 | Revision of key points of lectures | |||||

| 15 | Can be extended to other departments | |||||

| 16 | Debriefing of role play further reinforced communication skills | |||||

19. Any suggestions or comments on role play from student's perspective?

Annexure 4

Annexure 4.

Role play questionnaire for faculty

| 1 | Name (optional) | Designation | Teaching experience | |||

| 2 | Use of role play in learning communication skills in pediatrics | |||||

| 3 | Variable | Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| 4 | Participation by students was livelier | |||||

| 5 | Teaching was more Interesting | |||||

| 6 | Breaks monotony | |||||

| 7 | Communication skills taught with more objectivity | |||||

| 8 | Attitude as a doctor improved | |||||

| 9 | Revision of key points of lectures | |||||

| 9 | Mimicked Real case scenarios | |||||

| 10 | Easier transition to ward cases | |||||

| 11 | Mandatory to incorporate in UG Teaching | |||||

| 12 | Debriefing further stressed upon communication skills | |||||

| 13 | Clinical features remembered better | |||||

| 14 | Can be extended to other topics as well as other departments | |||||

17. Any suggestions or comments on role play from faculty's perspective?

References

- 1.Yedidia MJ, Gillespie CC, Kachur E, Schwartz MD, Ockene J, Chepaitis AE, et al. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA. 2003;290:1157–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joekes K, Noble LM, Kubacki AM, Potts HW, Lloyd M. Does the inclusion of ‘professional development’ teaching improve medical students’ communication skills? BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rider EA, Hinrichs MM, Lown BA. A model for communication skills assessment across the undergraduate curriculum. Med Teach. 2006;28:e127–34. doi: 10.1080/01421590600726540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausberg MC, Hergert A, Kröger C, Bullinger M, Rose M, Andreas S, et al. Enhancing medical students’ communication skills: Development and evaluation of an undergraduate training program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee S, Choudhury N. Medical communication skills training in the Indian setting: Need of the hour. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5:8–10. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.75968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shukla AK, Yadav VS, Kastury N. Doctor-patient communication: an important but often ignored aspect in clinical medicine. JIACM. 2010;11:208–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virshup BB, Oppenberg AA, Coleman MM. Strategic risk management: Reducing malpractice claims through more effective patient-doctor communication. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:153–9. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz S, Draper J, Silverman J. 2nd ed. New York: CRC Press; 2004. Calgary-Cambridge guides communication process skills. In: Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine; pp. 44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyce BL, Steenbergh T, Scher E. Use of the Kalamazoo essential elements communication checklist (adapted) in an institutional interpersonal and communication skills curriculum. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:165–9. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00024.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: The Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mogra I. Roleplay in teacher education: Is there still a place for it? Teach Educ Adv Netw J. 2012;4:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikendei C, Kraus B, Schrauth M, Weyrich P, Zipfel S, Herzog W, et al. Integration of role-playing into technical skills training: A randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2007;29:956–60. doi: 10.1080/01421590701601543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosse HM, Nickel M, Huwendiek S, Jünger J, Schultz JH, Nikendei C, et al. Peer role-play and standardised patients in communication training: A comparative study on the student perspective on acceptability, realism, and perceived effect. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manzoor I, Mukhtar F, Hashmi NR. Medical students’ perspective about role-plays as a teaching strategy in community medicine. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012;22:222–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson VA, Back AL. Teaching communication skills using role-play: An experience-based guide for educators. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:775–80. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taveira-Gomes I, Mota-Cardoso R, Figueiredo-Braga M. Communication skills in medical students – An exploratory study before and after clerkships. Porto Biomed J. 2016;1:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pbj.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevenson K, Sander P. Medical students are from mars – Business and psychology students are from Venus – University teachers are from Pluto? Med Teach. 2002;24:27–31. doi: 10.1080/00034980120103441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nestel D, Tierney T. Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joyner B, Young L. Teaching medical students using role play: Twelve tips for successful role plays. Med Teach. 2006;28:225–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590600711252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. 6th ed. USA: Elsevier; 2005. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development; pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]