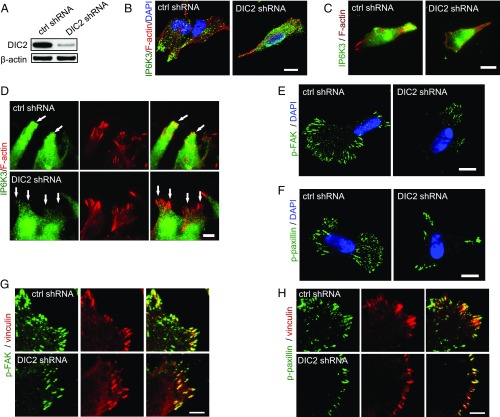

Fig. 4.

DIC2 drives IP6K3 to the leading edge. (A) Knocking down DIC2 in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells by shRNA transduction. (B–D) Immunostaining of IP6K3 in SH-SY5Y cells. (B) DIC2 knockdown disrupts the plasma membrane localization of IP6K3. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (C) TIRF microscopy reveals polarized intracellular distribution of IP6K3, which is enriched at the cell’s leading edge in control cells. Deletion of DIC2 disrupts IP6K3 distribution. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (D) TIRF microscopy demonstrates deletion of DIC2 abolishes the recruitment of IP6K3 to the leading edge in a wound-induced migration assay. (Arrows point to the leading edge.) (Scale bar: 5 μm.) (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy shows decreased density of phospho-FAK (Y397) at cell periphery in DIC2 knocked-down SH-SY5Y cells. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (F) Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates decreased density of phosphopaxillin at the cell periphery in DIC2-deleted SH-SY5Y cells. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) (G) High magnification shows at the cell periphery the density of phospho-FAK (Y397) is dramatically decreased in DIC2 knocked-down SH-SY5Y cells. (Scale bar: 5 μm.) (H) High magnification shows at the cell periphery the density of phosphopaxillin is substantially decreased in DIC2 knocked-down SH-SY5Y cells. (Scale bar: 5 μm.)