SUMMARY

Background:

More than half of pregnancies in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus) result in adverse outcomes for both the mother and fetus. We sought to identify aspects of current rheumatologic care that could be improved to decrease the frequency of poor outcomes.

Methods:

Focus groups with clinical rheumatologists, based on the PRECEDE/PROCEED framework, identified factors that influenced care. A group of women with lupus on their reproductive journey contributed to our understanding of the dilemmas and care provided.

Results:

Medically ill-timed pregnancies and medication non-adherence during pregnancy were identified by rheumatologists as the two key dilemmas in care. We identified several communication gaps as key modifiable barriers to optimal management. The approach to physician/patient communication was often unsuitable to sensitive discussions about pregnancy planning. The communication of treatment plans was frequently hampered by gaps in knowledge and confidence in data, encouraging non-adherence among nervous patients. Finally, local rheumatologists and OB/GYN providers frequently did not communicate, leading to varying treatment plans and confusion for patients.

Conclusion:

To decrease the frequency of ill-timed pregnancy and medication non-adherence it will be essential to empower rheumatologists and women with lupus to have open and accurate conversations about pregnancy planning and management.

INTRODUCTION

The rates of success of pregnancies in women with systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus) have improved dramatically over the past 60 years, likely due to advances in both rheumatic and obstetric care. The recent PROMISSE (Predictors of Pregnancy Outcome: Biomarkers in APL Syndrome and SLE) study demonstrated that up to 80% of pregnancies in women with mild to moderate lupus, when managed by experts at university centers, can be delivered at term without complications.1 Whether these outcomes are reproducible outside of these rarified clinics, however, is untested. Data suggest that management of lupus in pregnancy by ‘experts’ is different from that delivered in many community clinics. For example, continuing hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) throughout pregnancy has been a fairly routine practice among experts since the mid-1990’s, with approximately 75% of pregnancies in the Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Cohort exposed to this medication since 2000.2 On the other hand, Medicaid datasets suggest that just under 40% of pregnant women with lupus take HCQ, suggesting a large gap in physician prescribing and/or patient compliance with this medication.3,4

The goal of this study was to identify the influencing factors that result in the current management of lupus during pregnancy among community and university rheumatologists. We used the structure of the PRECEDE-PROCEDE framework5 to design a mixed-methods approach to reach this goal. In this model, the target intervention population (community & university rheumatologists), were queried to identify the key factors that determined their management of lupus in pregnancy. We engaged with community rheumatologists at national, state, and local rheumatology association annual meetings, soliciting qualitative data through focus groups. We also consulted with a group of women with lupus at various stages of their reproductive course to gain insight into the patient perspective. Through this process we sought to identify key factors that influence physician decision-making and practices that may diminish their ability to provide optimal care to women with lupus during pregnancy.

METHODS:

Focus Groups:

One to two focus groups were held at each state rheumatology meeting in North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and California. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. Each focus group included between 2 and 12 rheumatologists and lasted 60–120 minutes. Each was located in a meeting room at the same location as the state-wide conference. Physician participants were invited via email from the meeting organizers and in-person during the conference so as to represent a range of ages and training programs. Physicians were compensated $100 for their time and participation. Each session was audiotaped. We met thematic saturation at the completion of 8 focus groups. This study was approved by Duke Health IRB (Pro00070302).

After providing informed consent, each participant completed a brief questionnaire about their demographics and practice characteristics as well as goals of therapy and decision-making challenges. Some participants completed this on paper and others completed it online via a Qualtrics survey; most participants completed the survey prior to the focus group but some completed it following the discussion due to time constraints.

All focus group participants were active rheumatology clinicians, the majority of whom worked in community or private practice settings. Several of the participants were nurse practitioners active in rheumatologic clinical care. Several participants were university-based rheumatology physicians; these participants were not included in the larger focus groups and underwent small-group interviews.

The focus group questions were adapted iteratively throughout the study based on the responses in the prior groups. An expert in focus group facilitation moderated the initial sessions in Virginia and South Carolina, and Dr. Clowse moderated the remaining sessions after training. Dr. Clowse attended all focus groups.

Patient Advisors & Collaborators:

The Duke Autoimmunity in Pregnancy Patient Advisors and Collaborators (DAPPAC) is a group of women with lupus or a lupus related illness between the ages of 20 and 45. All DAPPAC members provided informed consent. They were invited to attend monthly meetings to discuss the challenges of pregnancy while living with lupus, as well as assisted in interpreting the data collected from community rheumatologists. The study team presented and led a discussion about the study findings as they were obtained to understand the patient’s perspective. All meetings were recorded, and during sessions, study team members took notes and debriefed after. Recordings were listened to as needed to clarify discussion themes and to collect direct quotes. The DAPPAC was approved by Duke Health IRB (Pro00071537).

Data Analysis:

Prior to the initial focus group, a summary template that included the key components of the PRECEDE model was made by the study team.5 Following each focus group, the focus group facilitator and Dr. Clowse discussed and documented the key points learned for each of these areas. In addition, detailed notes were taken about specific answers to the questions both in the focus group guide and that evolved during discussion.

Each focus group session was recorded and transcribed. Two team members (JR and AME) independently reviewed a small sample of three transcripts to develop a preliminary list of themes. From this list, one team member (JR) reviewed all transcripts and developed a code list. Two team members (JR and AME) then independently reviewed and coded all transcripts. The two coders reviewed coded transcripts together, discussed any discrepancies, and collated codes to identify emergent themes across focus group sessions. The research team then reviewed all of the coded data, as well as the initial notes, to draw conclusions about the influencing factors identified through this exercise.6

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 36 clinicians participated in the 8 focus groups, with 32 participants completing the surveys (Table 1). Of these, 63% were female. The majority of participants were white (68%), with 21% self-identifying as Asian and 11% as black; none were Hispanic. The average age was 44 with a range between 28 and 67. While 25% of the participants were in a university practice, the rest were in private (41%), group (22%), or a hospital-managed practice (9%). Most (68%) saw patients for at least 75% of their work effort. Half of the participants worked in an urban setting, with just 7% (two people) working in rural settings. The physicians had been in practice for an average of 12 years, with three being current rheumatology fellows and one reporting 36 years in practice. They reported seeing an average of 13 lupus patients per week, with a range between 1–90, and half of the rheumatologists reported seeing fewer than 10 per week. They reported seeing a median of 3 pregnant lupus patients per year, with a few university-based physicians seeing over 20 per year. On average, the participants estimated that 16% of their patients received Medicaid with several reporting no patients with Medicaid and several with up to 30–50% representing this population. While 13 participants estimated that more than half of their patients were white, another 14 reported serving over 30% black populations and 11 reported over 30% Hispanic populations.

Table 1.

Physician and clinical practice characteristics (n=32 clinicians*)

| Physician Characteristics | |

| Female | 63% |

| Mean age (range) | 44 (28–67) |

| Race | |

| White | 68% |

| Asian | 21% |

| Black | 11% |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Mean duration in practice (range), years | 12 (fellow to 36yrs) |

| Practice Characteristics | |

| Practice Setting | |

| University | 25% |

| Non-university | 75% |

| Patient load, >75% effort patient care | 68% |

| Average lupus patients seen per week (range) | 13 (1–90) |

| Median lupus pregnancies seen per year (range) | 3 (1–50) |

| Patient Characteristics (per the rheumatologists) | |

| Medicaid | 16% (0–100%) |

| Racial make-up of patient population | |

| >30% Black | 14 MDs |

| >30% Hispanic | 11 MDs |

A total of 36 clinicians participated in the 8 focus groups, with 32 participants completing the surveys.

The DAPPAC is a self-described “mixed bag” of racially diverse women with lupus, aged 21 to 45 years, at various points in their pregnancy journey. They describe themselves as “women who want to have families regardless of their medical situation.” A total of 15 women are officially enrolled in the DAPPAC with between 6–11 presenting for each monthly meeting.

Key Clinical Dilemmas Identified by Rheumatologists (Table 2):

Table 2.

Key clinical dilemmas identified by rheumatologists.

| Theme |

|---|

| Medically ill-timed pregnancies |

| Medication adherence in pregnancy |

|

| Physician-patient communication |

| Coordination of care between rheumatologists and other physicians |

Medically ill-timed pregnancies:

A lupus patient having a medically ill-timed pregnancy, meaning a pregnancy that occurs when a woman is taking a teratogenic medication or has active lupus, is the dilemma most reported by rheumatologists in focus groups. Most rheumatologists could recall at least one pregnancy conceived on a teratogenic medication or during a period of high disease activity. Some were afraid of managing this complicated situation and having little control of the outcome: “…That’s part of the fear, I think…They come in crashing, and then it’s like you’re responsible, and you’re not sure that you’re going to be able to fix that.” Interestingly, fear of litigation was not reported as a frequent concern and no rheumatologist, when asked directly, could remember a colleague who had been sued over a pregnancy mishap. Others reported anger that women did not avoid pregnancy, feeling betrayed by the patient: “I [get] angry—when the patient comes in after multiple discussions on toxic medicine and, ‘Oops, I’m pregnant,’ despite them getting Depo or birth control or whatever it is that we’ve talked about and thought they were actually doing… And if they can’t take their birth control methods, then I worry that they’re not even taking their lupus medications appropriately.”

Medication adherence in pregnancy:

Rheumatologists identified two aspects of medication adherence in their discussions: limited patient trust in their providers’ recommendation and gaps in clinician knowledge about which medications to prescribe. Some rheumatologists reported that patient distrust in them and the available data were the main causes for limited medication compliance in pregnancy. Rheumatologists reported that some women had preconceived ideas about treatment in pregnancy – typically that all medications should be avoided – that were hard to overcome. One rheumatologist in the North Carolina focus group described this distrust by stating, “And I’ve felt a lot of times, there’s distrust in the medical community that plays into that, especially in minorities.” Another said that patients struggle with deciding “does this person want to hurt me and my baby, or do they want to help me and the baby?”

In the focus groups, 28% reported that their largest challenge was knowing which medications were safe in pregnancy. They expressed concern about using certain medications in pregnancy, with one physician stating, “…azathioprine… I know we’re supposed to use it in lupus in pregnancy, but it went from a Class C to a Class D, and that makes me really nervous when you start reading about kind of all the teratogenic effects, so it’s hard for me to counsel my patients to take something like that.” (Note: mycophenolate switched from Class C to D, not azathioprine; azathioprine has always been Class D but is felt to be the safest immunosuppressant in pregnancy.) We suspect that these knowledge gaps and the rheumatologists’ lack of confidence in drug safety make it difficult for them to discuss medication use in pregnancy with their patients in a way that would encourage a woman to take the medication.

Physician-patient communication style:

Initiating the conversation about contraception and pregnancy was identified as a common challenge. One rheumatologist noted the anxiety of not wanting a patient to bring up the topic of pregnancy by stating, “She’s doing so well, and I was almost biting my (tongue) … I didn’t want her to ask me that pregnancy question.” Another rheumatologist noted the importance of bringing up the topic of pregnancy to aide in pregnancy planning, saying, “If you don’t bring it up, they’ll just get pregnant.” Finally, there was discussion around the difficulty of patients wanting to engage in the conversation with rheumatologists, “… but sometimes they don’t want to talk about it. I try to bring it up and they kind of push it aside.”

While most rheumatologists reported bringing up contraception frequently, few had an approach that would give a woman an open opportunity to share her thoughts about pregnancy. Instead, the focus was largely on confirming that women were using contraceptives: “You’re going through their medication list and you’re going through their CellCept and their Plaquenil and then there’s birth control there and then I go, ‘Are you taking it?’ I mean, you can ask, ‘Are you taking it now?’ And then it automatically kind of leads to that, you know, ‘Because you shouldn’t get pregnant.’” For a woman who is hesitant to share her desire to get pregnant due to shyness or fear of judgement, the easiest answer to ‘Are you taking your birth control?’ is ‘Yes,’ even if this is not the truth.

Physicians also reported time limitations in clinic and some degree of fatigue in discussing contraception and pregnancy planning at every visit. Very few reported having a reminder in their clinic note to cover the topic, making it one more thing to remember in the midst of a busy visit with a complicated patient.

On the other hand, some rheumatologists use a different approach to discuss medication use in pregnancy that appealed to the patient’s desire for a healthy baby. These rheumatologists discussed medication use in pregnancy as a benefit to the baby, not primarily the mother: “I think they care more about the baby’s health than their own, so if I show them that there’s data that the baby actually has better outcomes in pregnancy if they’re on the Plaquenil, then they’re more willing to do it. But if you say, “You’re gonna do better,” then they’re not as convinced. So you have to convince them that it’s better for the baby.”

Coordination of care between rheumatologists and other physicians:

In focus groups, physicians frequently discussed the barrier of coordination of care between rheumatologists and other physicians caring for their patient. The limited communication between rheumatologists and obstetricians/gynecologists (OB/GYN) manifests in multiple ways, including differences in contraception and medication recommendations, repeating labs unnecessarily, and limited communication about specific patients as rheumatologists and OB/GYN often do not personally know each other.

Rheumatologists were frustrated with some patients not being able to obtain contraception from their gynecologist, with one physician stating that women reported gynecologists saying “[you] can’t go on birth control because [you’re] on MMF.’ Or, ‘You’re on immunosuppressants, you can’t do a foreign body like an IUD.’” As the rheumatologists reported rarely seeing gynecology notes, it is difficult to know if this is what a gynecologist told the patient or what the patient remembered incorrectly. It is clear, however, that this rheumatologist, patient, and OB/GYN are not working as a team to get a patient on effective contraceptive.

While rheumatologists reported that the majority of obstetricians supported their prescription of hydroxychloroquine and usually azathioprine in pregnancy, many had memorable cases of obstetricians stopping these drugs. One physician stated, “I get frustrated with the OB, too, because I recently had one question my judgment on continuing hydroxychloroquine.” Another physician expressed similar concerns with azathioprine, stating, “…I wanted the patient to use azathioprine, they were discussing with the other doctor, whether it was a primary care or OB/GYN said, ‘Oh, I don’t know, this is pregnancy Class [D], I’m not sure you should be on it.’”

On the other hand, some rheumatologists reported great relationships with their local obstetrical teams. One rheumatologist said, “I generally talk to the OB and let them know that she has lupus and … what she’s been on and kind of discuss what their comfort level of trying to see what we need to continue and what I think would be good for them to continue.” In the Northern California area, in particular, there is clearly a strong connection between the rheumatologists and the Maternal-Fetal Medicine teams, built around Stanford University. As one described, “There’s a maternal fetal group of four or five different gynecologists who’re very familiar with our group of patients. So, I think they’re pretty comfortable.”

The Duke Autoimmunity in Pregnancy Patient Advisors and Collaborators:

The women in the DAPPAC voiced different perspectives and experiences about their relationships and conversations with their rheumatologists (Table 3).

Table 3.

Key clinical dilemmas identified by women with lupus.

| Theme |

|---|

| Lack of open conversations about pregnancy planning |

| Lack of trust in physicians |

| Intense desire to have a baby more important that the risks of pregnancy |

| Balance of risks & benefits of pregnancy different for patients and physicians |

Lack of Open Conversations about Pregnancy Planning:

Most women, regardless of education level or socioeconomic status, reported feeling intimidated by their rheumatologist and therefore hesitant to speak up about their true pregnancy desires. Almost all of the women in the group reported that, at some point, she had been untruthful about contraceptive use to her rheumatologist. They reported that they were not honest because they did not want to hear ‘the speech,’ meaning the often guilt- and fear-laden discussion of the risks of pregnancy. They also wanted to avoid confrontation with their rheumatologist, from whom they wanted approval and needed assistance.

Lack of trust in physicians:

The DAPPAC also addressed the feeling of distrust that they have with some clinicians, reporting a strong dependence on the internet to confirm what they have been told in clinic. Most women participated in at least one online patient-driven social media group, and used this, as well as university-affiliated and foundation-affiliated websites for information. All patients confirmed that they ‘Googled’ every new prescription they were given before taking it. Many women would use the online information they found to determine whether they would take the medications, with this information potentially trumping the recommendation of their physician.

Intense desire to have a baby more important that the risks of pregnancy:

Women in the DAPPAC discussed reasons why women with lupus may not be upfront with their rheumatologist about their pregnancy intentions. The most commonly discussed reason was their intense desire to be a mother, with one DAPPAC member saying the “desire to be a mother is greater than the risk you hear.” Another member described why, even after discussing the risks of pregnancy and the appropriate medications to take, women may move forward with their own pregnancy plan even against their rheumatologist’s recommendation, “I know [getting pregnant] isn’t the best for me … but I want to get pregnant.”

Balance of risks & benefits of pregnancy different for patients and physicians:

Finally, we found a wide difference in the way that rheumatologists and patients think about the risks and benefits of pregnancy. From our discussions, many rheumatologists could not understand why women at high-risk for complications – risks to her own health, risks of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, or birth defects – would make the decision to get pregnant or remain pregnant. The women, in most situations, placed the value of becoming a mother and having a child far above these risks. While they were concerned about the risks, the idea of never becoming a mother was simply unacceptable to most of them.

Discussion

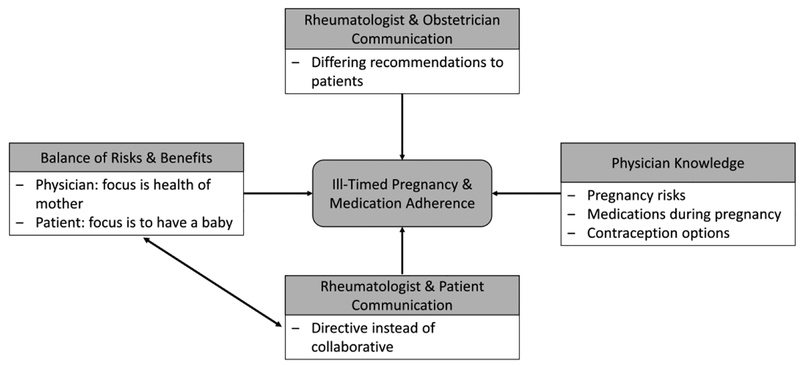

The rheumatologists in this study identified medically ill-timed pregnancies and medication non-adherence as the two main challenges that, if improved, might optimize their management of lupus in pregnancy. The perspective provided by the women in the DAPPAC transformed our understanding of the perceived physician dilemmas. What rheumatologists assumed were unplanned pregnancies that occurred due to patient disregard of their advice were actually, often, planned or at least not avoided. Women with lupus decide to have a baby based on the circumstances of their life, much like the rest of us decide to have a baby. Living with lupus, and the risks that this brings, was an obstacle that they had to overcome, but for the majority of women the drive to have a baby far outweighed these risks. Through our discussions with both rheumatologists and women with lupus, we have identified gaps in communication – between physicians and patients, as well as between different physicians – as key drivers for the frequency of these dilemmas (Figure 1). Our data suggest that enabling rheumatologists to engage in open – meaning gaining honesty from patients about pregnancy intentions – and accurate – meaning the physician provides correct information about contraception and medication – conversations about pregnancy planning will elevate the care provided during this crucial period.

Figure 1.

Patient and physician factors leading to ill-timed pregnancy and medication adherence.

The careful timing of pregnancy is essential for pregnancy success. The NIH-funded PROMISSE study demonstrated that low-risk women with lupus can have pregnancy outcomes comparable to the general population.1 Unintended pregnancies are at higher risk for congenital anomalies and poor functioning in early childhood for all women, but can be particularly risky among women with lupus.7 When unplanned pregnancies occur during a lupus flare, the risks for pregnancy loss, preterm birth, and maternal complications all increase.8 Additionally, many women with lupus of reproductive age take a “rheumatic teratogen.” These medications, including methotrexate, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and lenalidomide, dramatically increase the risk for both pregnancy loss and major birth defects.9 We have recently completed both patient and physician surveys that indicate that over 15% of lupus pregnancies are conceived on a rheumatic teratogen.10 It is not surprising that unplanned pregnancy is so common, as 1/3 of women with lupus starting teratogenic medications are given no instructions to avoid conception.11

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines for lupus management in pregnancy emphasize controlling lupus through the use of compatible medications, particularly hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and prednisone only when needed.9 They also recommend against the use of rheumatic teratogens. In addition, they encourage the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives like the intrauterine device (IUD) or progesterone implant, as well as the use of emergency contraception, if needed. Communicating these recommendations to women with lupus prior to and during pregnancy in a way that is acceptable and compelling is essential to encourage medication adherence. Gaps in this knowledge, or limited confidence in this data, prevents some rheumatologists from presenting a persuasive argument for these treatments. When women have local rheumatologists and OB/GYN with differing views on contraception and medication use in pregnancy, they are unable to follow these plans.

There are important non-modifiable barriers to improving lupus pregnancy outcomes, including limited clinic time, socio-economic circumstances, and the physiology of lupus in pregnancy. Limited time in clinic, particularly for a complicated disease like lupus in which multiple competing issues need to be discussed during a visit, can be a barrier to repeatedly discussing contraceptive needs. The socioeconomic impact and racial disparities seen in pregnancy outcomes in women with lupus is dramatic, with African-American women having 2–3-fold higher rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes.1,12 Much of this difference may be due to maternal education and community income, as recently demonstrated in the PROMISSE study.13 While rheumatologists can’t transform the socio-economic circumstances of women with lupus, it is important that we keep these in mind, and particularly focus on those with the highest level of risk, to see gains in outcomes.

The findings in this study match those of similar projects with other sub-specialists. For women with HIV, providers also often have limited knowledge of up-to-date data about contraception and conception, and thus avoid discussions about these important topics. Women who report a closer relationship with their physician and greater satisfaction in their gynecology appointment have higher uptake and continued use of contraceptive use.14–16 Communication that focuses on understanding the woman’s needs, concerns, and plans has been shown to lead to higher rates of contraceptive use than directive or authoritarian methods. Directing or coercing women to use a specific contraceptive, in fact, appears to significantly decrease her rate of use.17,18 Task-oriented communication, with the provision of accurate, useful, and patient-accessible data, is also an important component to contraceptive education.19

The gaps in physician/patient and physician/physician communication identified through this work can be overcome, we believe, through patient- and physician-oriented interventions. Coupling these programs with the publication of the upcoming American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Guidelines for Reproductive Health Management will be essential to allow the full impact of these guidelines to match the clinical need. These guidelines, with anticipated publication in 2019, will provide rheumatologists with a road-map for preconception and pregnancy care for women with lupus. Increasing physician knowledge may improve the accuracy of physician advice. But to decrease the frequency of ill-timed pregnancy and medication non-adherence, it will be essential to transform physician-patient communication to encourage patient disclosure of beliefs and attitudes and provide guidance in a format that is trusted and appropriate.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the rheumatologists and the women of the DAPPAC who participated in our study, the organizers of the state rheumatology conferences who facilitated our focus groups, Kate Murray for leading focus groups, and Dr. Jennifer Gierisch for her assistance.

Funding: This research was funded by AHRQ grant 5K18HS023443.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: MEB Clowse is a consultant for UCB and has received research grants from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer Inc. and Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. AM Eudy has received funding through a medical education grant from GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Buyon JP, Kim MY, Guerra MM, et al. Predictors of pregnancy outcomes in patients with lupus: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eudy AM, Siega-Riz AM, Engel SM, et al. Effect of pregnancy on disease flares in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77: 855–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, et al. Brief report: patterns and secular trends in use of immunomodulatory agents during pregnancy in women with rheumatic conditions. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 1183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmsten K, Simard JF, Chambers CD, Arkema EV. Medication use among pregnant women with systemic lupus erythematosus and general population comparators. Rheumatology 2017; 56: 561–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gielen A, McDonald E, Gary T, Bone L. Using the precede-proceed model to apply health behavior theories In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods 2006; 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Gynecology. Committee Opinion No. 654: Reproductive life planning to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 127: e66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. The impact of increased lupus activity on obstetric outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotestam Skorpen C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A, et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 795–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clowse M, Eudy A, Revels J, Sanders G, Criscione-Schreiber L. Rheumatologists’ knowledge of contraception, teratogens, and pregnancy risks. Obstet Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson S, Trupin L, Yazdany J, Yelin E, Barton J, Katz P. Who receives contraception counseling when starting new lupus medications? The potential roles of race, ethnicity, disease activity, and quality of communication. Lupus 2016; 25: 12–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clowse ME, Grotegut C. Racial and ethnic disparities in the pregnancies of women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 2016; 68: 1567–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplowitz ET, Ferguson S, Guerra M, et al. Contribution of socioeconomic status to racial/ethnic disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes among women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 2018; 70: 230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koenig MA, Hossain MB, Whittaker M. The influence of quality of care upon contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann 1997; 28: 278–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.RamaRao S, Lacuesta M, Costello M, Pangolibay B, Jones H. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2003: 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanogo D, RamaRao S, Jones H, N’Diaye P, M’Bow B, Diop CB. Improving quality of care and use of contraceptives in Senegal. Afr J Reprod Health 2003; 7: 57–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson JT, Raine T, Schalet A, Blum M, Harper CC. “I wouldn’t be this firm if I didn’t care”: preventive clinical counseling for reproductive health. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 82: 254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moskowitz E, Jennings B. Directive counseling on long-acting contraception. Am J Public Health 1996; 86: 787–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dehlendorf C, Krajewski C, Borrero S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2014; 57: 659–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]