Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the impact of bacteriospermia on semen parameters.

Materials and methods: We used the Medline (1966-2017), Scopus (2004-2017), Clinicaltrials.gov (2008-2017), EMBASE, (1980-2017), LILACS (1985-2017) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL (1999-2017) databases in our primary search along with the reference lists of electronically retrieved full-text papers. Meta-analysis was performed with the RevMan 5.3 software.

Results: Eighteen studies were finally included. Men were stratified in two groups, healthy controls (5,797 men) and those suffering from bacteriospermia (3,986 men). Total sperm volume was not affected by the presence of bacteriospermia when all pathogens were analyzed together (MD 0.02 95%CI -0.13,0.17). Both sperm concentration (MD -27.06, 95% CI -36.03, -18.08) and total sperm count (MD -15.12, 95% CI -21.08, -9.16) were significantly affected by bacteriospermia. Decreased rates of normal sperm morphology were also found (MD -5.43%, 95% CI -6.42, -4.44). The percentage of alive sperm was significantly affected by bacteriospermia (MD -4.39 %, 95% CI -8.25, -0.53). Total motility was also affected by bacteriospermia (MD -3.64, 95% CI -6.45, -0.84). In addition to this, progressive motility was significantly affected (MD -12.81, 95% CI -18.09, -7.53). Last but not least, pH was importantly affected (MD 0.03, 95% Cl 0.01, 0.04).

Conclusion: Bacteriospermia significantly affects semen parameters and should be taken in mind even when asymptomatic. Further studies should evaluate the impact of antibiotic treatment on semen parameters and provide evidence on fertility outcome.

Key Words: Sperm, Semen, Infection, Fertility, Bacteriospermia, Meta-Analysis

Introduction

Bacteriospermia is diagnosed when bacteria in the ejaculate exceed 1000 cfu/ml (1). It is usually the result of acute or chronic bacterial infections and is regarded as a major health care problem which has a negative impact on male fertility (1-3). Specifically, it has been shown that approximately 15% of infertile men have significant number of bacterial pathogens in the sperm (1). Bacterial infections may affect various sites of the male genitourinary system, such as the prostate, the epididymis, the testis and the urethra (1, 3). The most common isolated pathogenic bacteria are Escherichia Coli, Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasmaurealyticum, Mycoplasma, Staphylococci, Streptococci and Enterococcus faecalis (1, 4).On the other hand, the male urinary system is not completely sterile as it has been already shown that certain bacteria, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, are identified in otherwise healthy reproductive men (4). The impact of different bacteria on sperm quality remains to date unknown (5).

The last decades, the constantly increasing population of infertile couples, has turned scientific interest towards the investigation of the impact of bacteriospermiaon male reproductive ability (6). Various pathophysiologic mechanisms have been investigated to confirm the correlation ofbacteriospermia with seminal parameters, including motility and vitality (7). It is speculated that both the direct bacterial interaction and the participation of the immune competent cells influence spermatogenesis, impair semen function and obstruct the urogenital tract (7, 8). However, the actual impact of each pathogen on seminal parameters remains unknown.

The purpose of our meta-analysis is to accumulate current knowledge in the field and to provide recommendations for clinical practice, as well as new scientific targets for the future.

Materials and methods

Study design: We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to design this systematic review (9). Eligibility criteria were predetermined by the authors. Language and date restrictions were avoided during the literature search. All observational studies (both prospective and retrospective, randomized and non-randomized) that reported the impact of bacteriospermia (irrespective of the pathogen) on seminal parameters were held eligible for inclusion and tabulation. Case reports and review articles were excluded. Animal studies were also excluded.

The study selection took place in three consecutive stages. In the first stage, two researchers (VP, NK) independently reviewed the titles and/or abstracts of all electronic articles to assess their eligibility. Next, the articles that met or were presumed to meet the criteria for inclusion in the present meta-analysis were retrieved in full text. During the third stage, two authors (NK, PK) tabulated the selected indices in structured forms. Potential disagreementsin the evaluation of the methodological quality, retrieval of articles, and statistical analysis were resolved after discussing with the remaining authors.

Literature search and data collection: We used the Medline (1966-2017), Scopus (2004-2017), Clinicaltrials.gov (2008-2017), EMBASE, (1980-2017), LILACS (1985-2017) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL (1999-2017) databases in our primary search along with the reference lists of electronically retrieved full-text papers. The date of our last search was set at 31stDecember, 2017. Search strategies and results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Search plot diagram

Our search strategy included the words semen; sperm; bacteria; bacteriospermia; infection; ureaplasma; mycoplasma; Neisseria; chlamydia; gardnerella; Escherichia coli; streptococcus. The PRISMA flow diagram schematically presents the stages of article selection (Figure 1).

Quality assessment: We assessed the methodological quality of all included studies using the Oxford Level of Evidence criteria and the GRADE list (10).

Statistical analysis: Statistical meta-analysis was performed with the RevMan 5.3 software (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011). Confidence intervals were set at 95%. We calculated pooled odds ratios (OR), mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) with the DerSimonian-Laird random effect model due to the significant heterogeneity of included studies (11). Similarly, publication bias was not tested due to the small number of studies and their gross heterogeneity (significant confounders that may influence the methodological integrity of these tests) (12).

Analyzed indices and subgroup analysis: The analyzed indices were tabulated in structured forms, which included significant sperm characteristics, such as sperm volume, Ph, total sperm count, concentration, normal morphology, total motile sperm count, progressive and total motility, sperm vitality and WBC. Subgroup analysis according to the type of pathogen was performed.

Results

Excluded studies: Twelve studies were excluded from the present meta-analysis as they either did not include a control group of infertile men or did not investigate the outcomes of interest (13-24).

Included Studies: Eighteen studies were finally included (25-42). Men were stratified in two groups, healthy controls (5,797 men) and those suffering from bacteriospermia (3,986 men). In the latter group, 858 patients suffered from mixed bacterial infection, 204 from Chlamydia trachomatis, 640 from Mycoplasma, 2,255 from Ureaplasma Urealyticum, 5 from Ureaplasma Parvum and 24 from Gardnerella vaginalis. The majority of available evidence was drawn from studies of low quality (Level of Evidence 2b and 3b –Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Date; author | Type of study | GRADE | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985; Grizard G. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men with significant bacteriospermia were included in the study. None of them had any clinical or gormonal abnormalities. |

| 1997; Bussen S. |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men who consecutively entered the IVF program of the clinic during a seven-month period in 1995 were included in the study. None of these patients had symptoms of genital tract infection or were treated with antibiotics 4 weeks before the treatment cycle. |

| 2003; L.Knox C. |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Male partners from couples who participated in an assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment cycle were included inb the study. |

| 2003; Rodin M.D. |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Asymptomatic men who were undergoing infertility evaluation were included in the study. |

| 2004; Hosseinzadeh S. |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men who attended the University Research Clinic (Jessop Hospital for Women, Sheffield, United Kingdom) for diagnostic semen analysis. All men were undergoing semen analysis as a part of a work-up for infertility suggestions after failing to conceive with their partner after one year of unprotected intercourse. |

| 2005; Sanocka- Maciejewska |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men with or without genital tract infection were included in the study. Men had no ability to conceive for at least 2 years of sexual intercourse. |

| 2005; Motrich R.D. |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men with Chronic Prostatitis Syndrome, whose age was 20-50 years, were included in the study. |

| 2006; De Barbeyrac B, |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men from couples who were undergoing an IVF program between January 1998 and November 2001 were included in the study. Men were between 18 and 55 years old and they didn’t have azoospermia. |

| 2006; Wang Y. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men aged 20-45 years who attended the andrology clinic in Shanghai Tonghi Hospital and SanghaiRenji Hospital from March 1, 2001 to March 1, 2003 were included in the study. All men did not present any reproductive abnormalities and had not received any antibiotic treatment. |

| 2008; Gdoura R. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men who were attending obstetrics and gynecology clinics in Sfax for infertility were included in the study. All patients did not present any clinical symptoms of genital tract infections except for their infertility health problem. |

| 2009; Andrade- Rocha |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men who had history of infertility for at least one year and had never received antibiotic treatment before semen analysis were considered as the patient group. |

| 2009; Gallegos – Avila G. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men from couples who were attending the andrology infertility clinic with diagnosed genitourinary infection from Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma were included in the study. The age of men ranged from 25-51 years. |

| 2009; A El feky | Case control | 3b | Men with leycocytospermia, who were attending the out- patient infertility clinic in the department of Dermatology, Venereology and Andrology, Assiut University Hospital during June 2007 to May 2008, were included in the study. Their age ranged from 24 to 49 years old. |

| 2010 Kokab A. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Consecutive men who were attending the Avesina Research Institute in Tehran, Iran for diagnostic semen analysis were included in the study. All men were undergoing semen analysis as a part of a work-up for infertility investigations with their partner after failing to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse. None of them reported any symptoms of genital tract infections. |

| 2011; De Francesco M.A. |

Retrospective cohort |

2b | Men who were referred to the Microbiology Laboratory Group of Brescia’s main hospital for semen analysis, as a part of infertility work-up were included in the study. Patients had visited the clinic between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2008. |

| 2012; Rybar R. et al |

Prospective cohort |

2b | Men with no urogenital tract discomfort with a minimum sexual abstinence of 2 days were included in the study. |

| 2013; Lee J.S. | Prospective study |

2b | Male partners from infertile couples without female factor subfertility and without reproductive or hormonal abnormalities were included in the study. |

| 2015; Huang C. et al |

Prospective study |

2b | Men of infertile couples who visited the Reproductive Center, the Reproductive and Genetic Hospital of CITIC, Xiangya, China, from January to December 2014 were included in the study. The men had failed to impregnate their wives after at least one year of unprotected intercourse. |

Outcomes: Total sperm volume was not affected by the presence of bacteriospermia when all pathogens were analyzed together (MD 0.0295%CI -0.13,0.17, Figure 2). However, mixed infection, Mycoplama hominis and Ureaplasmaparvum may be associated with decreased volume (evidence from eight studies).A significant increase of pH was observed (MD 0.03 95%CI 0.01, 0.04, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Mean differences of total sperm volume according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was not statistically significant (p = 0.80). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Figure 3.

Mean differences in pH according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

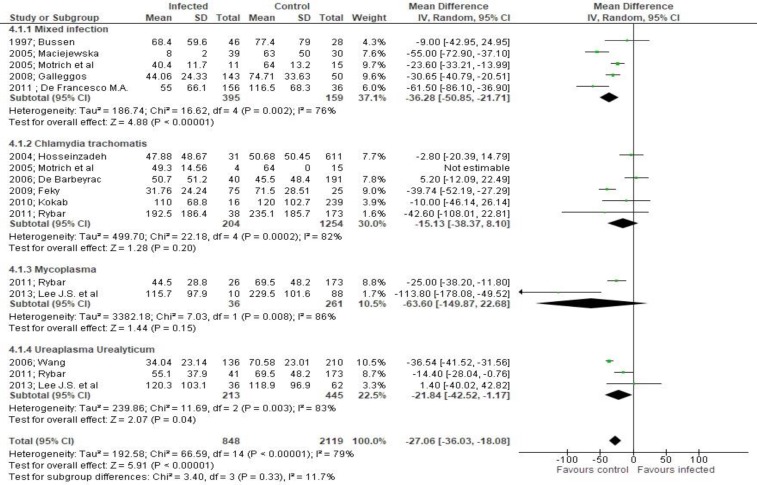

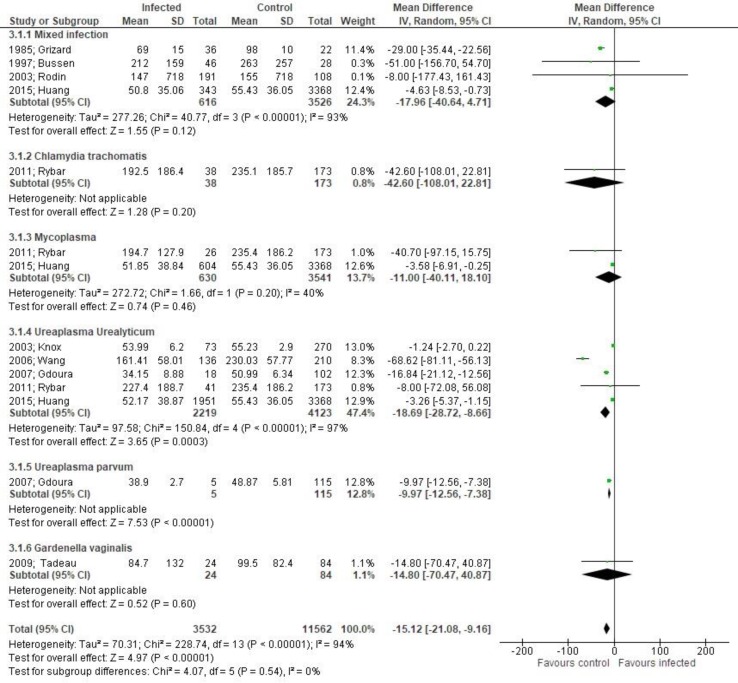

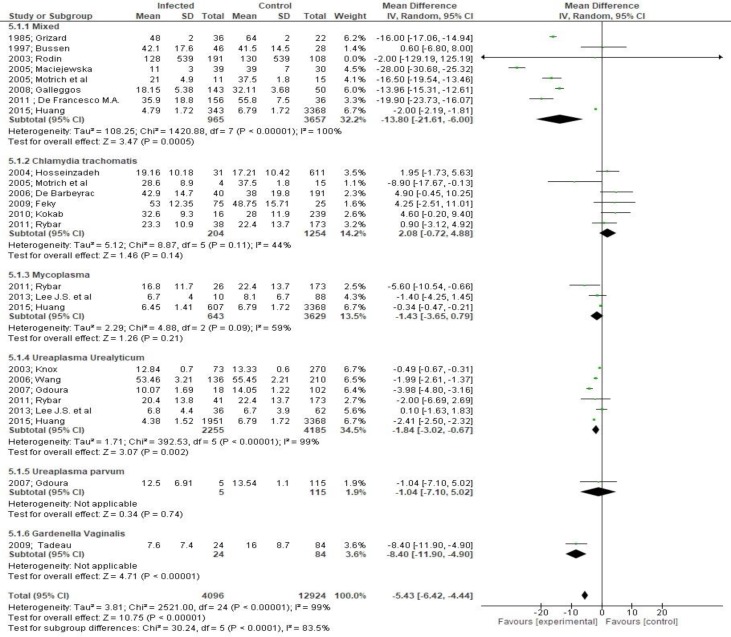

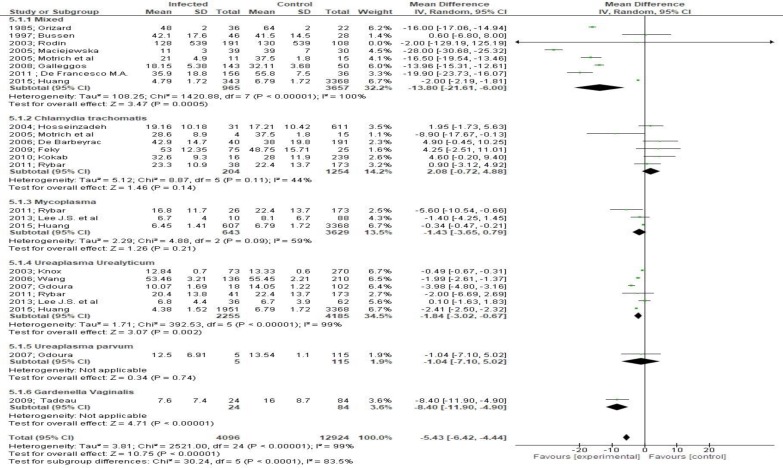

Both sperm concentration (MD -27.06, 95% CI -36.03, -18.08, Figure 4) and total sperm count (MD -15.12, 95% CI -21.08, -9.16, Figure 5) were significantly affected by bacteriospermia. Decreased rates of normal sperm morphology were also found (MD -5.43%, 95% CI -6.42, -4.44, Figure 6). The percentage of alive sperm was also affected by bacteriospermia (MD -4.39 %, 95% CI -8.25, -0.53, Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Mean differences of sperm concentration according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Figure 5.

Mean differences of total sperm count according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Figure 6.

Mean differences in normal sperm morphology according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Figure 7.

Mean differences in percentage of alive cells according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

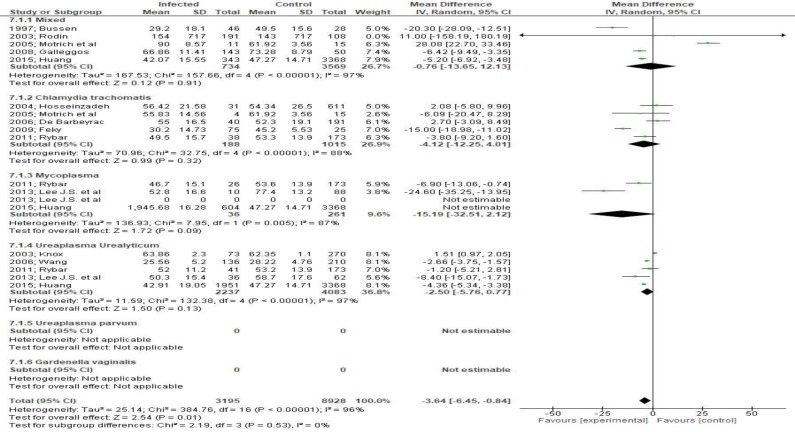

The assessment of motility parameters revealed that total motility was quite affected by bacteriospermia (MD -3.64, 95 CI -6.45, - 0.84 Figure 8). Moreover, progressive motility was alsoaffected significantly (MD -12.81, 95% CI -18.09, -7.53, p < 0.001 Figure 9) an effect that was not, however, evident in patients with Ureaplasma infection.

Figure 8.

Mean differences in sperm motility according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p < 0.01). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Figure 9.

Mean differences in progressive cell motility according to presence of bacteriospermia. The overall effect was statistically significant (p<.001). (Vertical line = "no difference" point between two groups. Squares = mean differences; Diamonds = pooled mean differences for all studies. Horizontal lines = 95% CI).

Sensitivity analysis: The findings of the sensitivity analysis did not significantly affect the aforementioned results.

Discussion

Both acute and chronic infections of the genitourinary tract are considered significant causative factors in male infertility (4).

The effect of bacteriospermia in semen quality is not fully understood as the accurate pathophysiologic impact of the various bacteria in semen parameters remains vague (7).

To date, to our knowledge, no previous meta-analyses in the field have been undertaken. In our meta-analysis we sought to gather all available evidence from the international literature to evaluate the influence of bacteriospermia in semen quality and male infertility.

According, to our findings significantly decreased rates have been found in several parameters such as total sperm concentration, total sperm count, normal morphology and progressive motility.

During the last decades, several studies have investigated the contribution of male factor and especially the role of bacteriospermia in couples’ infertility. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriospermia is associated with both acute and chronic inflammation of the genitourinary tract. Specifically, inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and reactive oxygen species, restrain the normal function of Sertoli cells leading to restricted spermatogenesis and unsuccessful acrosome reaction. As a consequence, many couples due to various unsuccessful efforts of automatic pregnancy, are led to in vitro fertilization. However, because of reduced inducibility of acrosome reaction, in vitro fertilization efforts often fail (43). Thus, appropriate antibiotic treatment, according to Bieniek et al., is necessary to improve semen characteristics and reduce couple subfertility rates.

Implications for current clinical practice and future research: According to the findings of the present systematic review, bacteriospermia clearly affects several semen parameters.

However, the impact of the various bacteria seems to differ. The clinical symptomatology does not necessarily correlate with the severity of these symptoms, as mild pathogens such as mycoplasma spp. may lead to significant alterations. Given these, clinicians should perform routine semen cultures when evaluating infertile couples and treat potential infections, despite the lack of substantial evidence for the effect of antibiotics on semen parameters.

Taking in mind the gaps in current literature, we strongly believe that future studies are needed to determine clearly the accurate impact of symptomatic or asymptomatic bacteriospermia in semen characteristics and to evaluate the effect of the various bacteria. Furthermore, given the lack of clinical data in the field of antibiotic treatment and fertility outcomes, future randomized trials will help us to evaluate the impact of the various antibiotics and compare them to placebo.

Strengths and limitations of the study: Our study is based in a meticulous review of the current literature as we investigated thoroughly the majority of electronic databases and the grey literature. However, selection bias partially limits interpretation of our findings as the majority of included studies did not use data from the general population, but rather couples attending IVF centers; hence, it remains unclear whether the actual differences reflect the truth in the general population.

Conclusion

Bacteriospermia seems to deteriorate semen parameters from normal values. However, current data are very limited as well as our understanding on the impact of antibiotic therapy on semen values. Future studies should focus on the impact of the various bacteria to corroborate our findings and enhance our knowledge in the pathophysiology and treatment of male infertility.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests.

Notes:

Citation: Pergialiotis V, Karampetsou N, Perrea DN, Konstantopoulos P, Daskalakis G. The Impact of Bacteriospermia on Semen Parameters: A Meta-Analysis. J Fam Reprod Health 2018; 12(2): 73-83.

References

- 1.Rusz A, Pilatz A, Wagenlehner F, Linn T, Diemer T, Schuppe HC, et al. Influence of urogenital infections and inflammation on semen quality and male fertility. World J Urol. 2012;30:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diemer T, Huwe P, Ludwig M, Hauck EW, Weidner W. Urogenital infection andsperm motility. Andrologia. 2003;35:283–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swenson CE, Toth A, Toth C, Wolfgruber L, O'Leary WM. Asymptomatic bacteriospermia in infertile men. Andrologia. 1980;12:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1980.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domes T, Lo KC, Grober ED, Mullen JB, Mazzulli T, Jarvi K. The incidence andeffect of bacteriospermia and elevated seminal leukocytes on semen parameters. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1050–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boitrelle F, Robin G, Lefebvre C, Bailly M, Selva J, Courcol R, Lornage J, Albert M. [Bacteriospermia in Assisted Reproductive Techniques: effects of bacteria on spermatozoa and seminal plasma, diagnosis and treatment]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2012;40:226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee HS, Park YS, Lee JS, Seo JT. Serum and seminal plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 in male infertility. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2016;43:97–101. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2016.43.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keck C, Gerber-Schäfer C, Clad A, Wilhelm C, Breckwoldt M. Seminal tract infections: impact on male fertility and treatment options. Hum Reprod update. 1998;4:891–903. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieterle S. Urogenital infections in reproductive medicine. Andrologia. 2008;40:117–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reportingsystematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health careinterventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, GreenhalghT , HeneghanC , Liberati A, et al. OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. “The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2″. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653.

- 11.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souza JP, Pileggi C, Cecatti JG. Assessment of funnel plot asymmetry and publication bias in reproductive health meta-analyses: an analytic survey. Reprod Health. 2007;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salmeri M, Santanocita A, Toscano MA, Morello A, Valenti D, La Vignera S, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis prevalence in unselectedinfertile couples. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2010;56:450–6. doi: 10.3109/19396361003792853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eley A, Pacey AA. The value of testing semen for Chlamydia trachomatis in men of infertile couples. Int J Androl. 2011;34:391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilvanathan S, Kandasamy B, Jayachandran AL, Sathiyanarayanan S, TanjoreSingaravelu V, Krishnamurthy V, et al. Bacteriospermia and Its Impact onBasic Semen Parameters among Infertile Men. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2016;2016:2614692. doi: 10.1155/2016/2614692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallegos-Avila G, Ortega-Martínez M, Ramos-González B, Tijerina-Menchaca R, Ancer-Rodríguez J, Jaramillo-Rangel G. Ultrastructural findings in semen samples of infertile men infected with Chlamydia trachomatis and mycoplasmas. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:915–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habermann B, Krause W. Altered sperm function or sperm antibodies are not associated with chlamydial antibodies in infertile men with leucocytospermia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamalizadeh Bahaabadi S, Mohseni Moghadam N, Kheirkhah B, Farsinejad A, Habibzadeh V. Isolation and molecular identification of Mycoplasma hominis ininfertile female and male reproductive system. Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6:e22390. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.22390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohseni Moghadam N, Kheirkhah B, Mirshekari TR, Fasihi Harandi M, Tafsiri E. Isolation and molecular identification of mycoplasma genitalium from thesecretion of genital tract in infertile male and female. Iran J Reprod Med. 2014;12:601–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mändar R, Raukas E, Türk S, Korrovits P, Punab M. Mycoplasmas in semen ofchronic prostatitis patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2005;39:479–82. doi: 10.1080/00365590500199822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samra Z, Soffer Y, Pansky M. Prevalence of genital chlamydia and mycoplasma infection in couples attending a male infertility clinic. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:69–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01717455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Mously N, Cross NA, Eley A, Pacey AA. Real-time polymerase chain reactionshows that density centrifugation does not always remove Chlamydia trachomatisfrom human semen. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dehghan Marvast L, Aflatoonian A, Talebi AR, Ghasemzadeh J, Pacey AA. Semeninflammatory markers and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in male partners ofinfertile couples. Andrologia. 2016;48:729–36. doi: 10.1111/and.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pajovic B, Radojevic N, Vukovic M, Stjepcevic A. Semen analysis before andafter antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic Chlamydia- and Ureaplasma-relatedpyospermia. Andrologia. 2013;45:266–71. doi: 10.1111/and.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Barbeyrac B, Papaxanthos-Roche A, Mathieu C, Germain C, Brun JL, Gachet M, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis in subfertile couples undergoing an in vitro fertilization program: a prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;129:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosseinzadeh S, Eley A, Pacey AA. Semen quality of men with asymptomatic chlamydial infection. J Androl. 2004;25:104–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Francesco MA, Negrini R, Ravizzola G, Galli P, Manca N. Bacterial speciespresent in the lower male genital tract: a five-year retrospective study. Eur JContracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16:47–53. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2010.533219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JS, Kim KT, Lee HS, Yang KM, Seo JT, Choe JH. Concordance of Ureaplasmaurealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in infertile couples: impact on semenparameters. Urology. 2013;81:1219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motrich RD, Cuffini C, Oberti JP, Maccioni M, Rivero VE. Chlamydia trachomatisoccurrence and its impact on sperm quality in chronic prostatitis patients. JInfect. 2006;53:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodin DM, Larone D, Goldstein M. Relationship between semen cultures, leukospermia, and semen analysis in men undergoing fertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(Suppl 3):1555–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybar R, Prinosilova P, Kopecka V, Hlavicova J, Veznik Z, Zajicova A, et al. The effect of bacterial contamination of semen on sperm chromatin integrity andstandard semen parameters in men from infertile couples. Andrologia. 2012;44(Suppl 1):410–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2011.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Feky MA, Hassan EA, El Din AM, Hofny ER, Afifi NA, Eldin SS, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis: methods of identification and impact on semen quality. Egypt J Immunol. 2009;16:49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knox CL, Allan JA, Allan JM, Edirisinghe WR, Stenzel D, Lawrence FA, et al. Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum are detected in semenafter washing before assisted reproductive technology procedures. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:921–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang C, Long X, Jing S, Fan L, Xu K, Wang S, et al. Ureaplasma urealyticumand Mycoplasma hominis infections and semen quality in 19,098 infertile men inChina. World J Urol. 2016;34:1039–44. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1724-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallegos G, Ramos B, Santiso R, Goyanes V, Gosálvez J, Fernández JL. Sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile men with genitourinary infection by Chlamydiatrachomatis and Mycoplasma. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gdoura R, Kchaou W, Chaari C, Znazen A, Keskes L, Rebai T, et al. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Ureaplasma parvum, Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasmagenitalium infections and semen quality of infertile men. BMC Infect Dis. 8;7:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grizard G, Janny L, Hermabessiere J, Sirot J, Boucher D. Seminal biochemistry and sperm characteristics in infertile men with bacteria in ejaculate. Arch Androl. 1985;15:181–6. doi: 10.3109/01485018508986909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kokab A, Akhondi MM, Sadeghi MR, Modarresi MH, Aarabi M, Jennings R, et al. Raised inflammatory markers in semen from men with asymptomaticchlamydial infection. J Androl. 2010;31:114–20. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.109.008300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanocka-Maciejewska D, Ciupińska M, Kurpisz M. Bacterial infection and semenquality. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;67:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Liang CL, Wu JQ, Xu C, Qin SX, Gao ES. Do Ureaplasma urealyticuminfections in the genital tract affect semen quality? Asian J Androl. 2006;8:562–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bussen S, Zimmermann M, Schleyer M, Steck T. Relationship of bacteriologicalcharacteristics to semen indices and its influence on fertilization and pregnancyrates after IVF. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:964–8. doi: 10.3109/00016349709034910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrade-Rocha FT. Colonization of Gardnerella vaginalis in semen of infertile men: prevalence, influence on sperm characteristics, relationship with leukocyte concentration and clinical significance. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68:134–6. doi: 10.1159/000228583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moskovtsev SI, Mullen JB, Lecker I, Jarvi K, White J, Roberts M, Lo KC. Frequency and severity of sperm DNA damage in patients with confirmed cases ofmale infertility of different aetiologies. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;20:759–63. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]