Abstract

To provide organisms with a fitness advantage, circadian clocks have to react appropriately to changes in their environment. High-intensity (HI) light plays an essential role in the adaptation to hot summer days, which especially endanger insects of desiccation or prey visibility. Here, we show that solely increasing light intensity leads to an increased midday siesta in Drosophila behavior. Interestingly, this change is independent of the fly's circadian photoreceptor cryptochrome and is solely caused by a small visual organ, the Hofbauer–Buchner eyelets. Using receptor knock-downs, immunostaining, and recently developed calcium tools, we show that the eyelets activate key core clock neurons, namely the s-LNvs, at HI. This activation delays the decrease of PERIOD (PER) in the middle of the day and propagates to downstream target clock neurons that prolong the siesta. We show a new pathway for integrating light-intensity information into the clock network, suggesting new network properties and surprising parallels between Drosophila and the mammalian system.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The ability of animals to adapt to their ever-changing environment plays an important role in their fitness. A key player in this adaptation is the circadian clock. For animals to predict the changes of day and night, they must constantly monitor, detect and incorporate changes in the environment. The appropriate incorporation and reaction to high-intensity (HI) light is of special importance for insects because they might suffer from desiccation during hot summer days. We show here that different photoreceptors have specialized functions to integrate low-intensity, medium-intensity, or HI light into the circadian system in Drosophila. These results show surprising parallels to mammalian mechanisms, which also use different photoreceptor subtypes to respond to different light intensities.

Keywords: circadian clock, Drosophila, photoreceptor

Introduction

Circadian clocks have evolved to allow animals and plants to predict the changes of day and night and thereby increase their fitness (Daan and Tinbergen, 1980; DeCoursey et al., 2000). A crucial property of circadian clocks is the ability to adjust their physiology and behavior to light–dark cycles, in a process called entrainment (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010).

In all clock cells, the transcriptional–translational feedback loop is believed to underlie these circadian rhythms of behavior. In short, Clock and Cycle activate period (per) and timeless (tim) transcription, respectively. PER and TIM proteins accumulate in the early night, reenter the nucleus toward the end of the night, and inhibit their own transcription (Hardin et al., 1990; Sehgal et al., 1994; Allada et al., 1998; Rutila et al., 1998).

In mammals, the circadian photoreceptor melanopsin in the retinal ganglion cells, as well as the rods and cones of the visual system, can transduce light information into the central brain clock, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Ebihara and Tsuji, 1980; Berson et al., 2002; Hattar et al., 2002). Similarly, flies can use the circadian photoreceptor cryptochrome (CRY) within most of the clock neurons as well as their visual system to synchronize their clock (Stanewsky et al., 1998; Rieger et al., 2003; Benito et al., 2008; Yoshii et al., 2008). The latter consists of the two compound eyes, three ocelli, and two Hofbauer–Buchner (HB) eyelets (Hofbauer and Buchner, 1989).

The clock neurons determine the diurnal behavior pattern of the fly. In light–dark (LD) cycles, flies show a bimodal locomotor activity pattern with a morning (M) peak and an evening (E) peak, which are clearly separated by a siesta. Essential groups of lateral neurons include the s-LNvs, which are important for morning anticipation (M activity) and are often referred to as M cells (Grima et al., 2004; Stoleru et al., 2004). The l-LNvs are important arousal centers (Shang et al., 2008). Additional circadian lateral neurons include three CRY-positive LNds, which dictate the E peak and are referred to as E cells.

In vitro experiments have investigated the connection of the visual system to the clock network. Whereas the compound eyes appear to be contacting the l-LNvs via cholinergic interneurons, the HB eyelets directly innervate the accessory medulla and increase Ca2+ and cAMP in the s-LNvs upon stimulation (Muraro and Ceriani, 2015; Schlichting et al., 2016). However, it is not understood how the visual system affects the rest of the central brain clock or how different light intensities affect these connections.

Studies in mammals and flies show that a complex visual system is required to adjust an animal clock to the light environment (Foster and Helfrich-Förster, 2001). At low intensity (LI), entrainment is predominantly performed by retinal rods, whereas melanopsin takes over at HI due to the saturation of the visual system by light (Lall et al., 2010; Lucas et al., 2012). In Drosophila, CRY is important for detecting LI due to its photon-integrating function (Vinayak et al., 2013) and four of the five rhodopsin-expressing photoreceptors of the compound eyes mediate entrainment at LI to moderate irradiances (Saint-Charles et al., 2016). Photoreception for HI is still unknown. However, flies lacking the whole visual system, as well as CRY, are unable to entrain to LD regimes of moderate light intensity (Helfrich-Förster et al., 2001).

In this study, we investigate how HI changes fly behavior and how it is incorporated into the clock network. HI significantly increases the fly siesta by delaying the E-activity onset. This phenotype is independent of CRY and the compound eyes, but does require the HB eyelets. We further show that the release of acetylcholine significantly increases in vivo Ca2+ and neuronal activity of the eyelet target neurons, the s-LNvs. Our data further suggest that HI delays PER degradation in the s-LNvs during the day. This change propagates throughout the network to change PER cycling of downstream target neurons, such as the DN1s, which have been implicated in the control of the siesta (Guo et al., 2016).

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

The following fly strains have been described previously and were used in this study: WTCS, WTALA (Sandrelli et al., 2007), WTLB (Schlichting et al., 2014), w1118, cry01 (Dolezelova et al., 2007), clieya (Bonini et al., 1993), rh61 (Cook et al., 2003), rh52 (Yamaguchi et al., 2008), ninaE17 (Kumar and Ready, 1995), sevLY3, clieya;rh61, norpAP24, nocte (Glaser and Stanewsky, 2005) hdcJK910(BL 64203), R6-GAL4 (Helfrich-Förster et al., 2007), UAS-mAchRA-RNAi (BL 44469, 27571), UAS-nAChR-RNAi (BL 31883, 28688), pdf-GS-GAL4 (Depetris-Chauvin et al., 2011), ActP-MKII::GAL4DBDo, ActP-p65AD::CaM (UAS-Tric) (Gao et al., 2015), and UAS-GFPS65T (BL 1522). All experiments were performed in male flies.

Behavior recording

Regensburg system.

Individual 2- to 5-d-old male flies were transferred into photometer half-cuvettes with water and sugar supply. The fly's activity was measured as IR beam crosses caused by the fly in 1 min intervals. Independent sets of flies were tested at LI (∼10 lux, 1 week duration) or HI (∼10.000 lux, 1week duration). Independent sets of flies were used to exclude behavioral effects due to aging.

Würzburg system.

Individual 2- to 5-d-old male flies were placed into glass tubes containing food (2% agarose, 4% sucrose). These glass tubes were placed in Drosophila activity monitors (DAMs) and the activity of the flies was measured in 1 min intervals. Flies were entrained for 1 week at LI (∼10 lux) followed by 1 week of HI (∼8000 lux). We were only able to reach 8000 lux due to a different position of the LEDs using the DAM system. Both light intensities were investigated within the same flies to follow changes in behavior within individual flies. All experiments were conducted within light boxes in climate-controlled chambers at a temperature of 20°C. To minimize fluctuations in temperature, each light box was equipped with a fan to constantly exchange the air within the light box.

Behavior analysis

All data were plotted as actograms using ActogramJ (Schmid et al., 2011). Subsequently, we calculated average activity and average sleep profiles using the last 4 d of each light condition as described previously (Schlichting and Helfrich-Förster, 2015). Sleep was measured as intervals of at least 5 min of inactivity. To determine the timing of M and E activity and onset/offset, we generated single-fly average days in 30 min bins. We then determined fly by fly the first time point when a fly's activity reached the siesta activity amount as the offset of M activity and the first time point of increased activity beyond siesta levels as E-peak onset. This analysis was done blindly by two independent investigators and we calculated the average value ± SEM. We further calculated a performance index (PI) to determine the flies' E-peak onset to overcome subjective determination of E-peak onset. The PI is calculated as follows: PI = sum of activity 3–6 h before E peak HI/sum of activity 3–6 h before E peak LI. A PI < 1 indicates a reduction of activity, which we interpret as a delay in E-peak onset. Data were compared using a Student's t test or a one-way t test comparing the PI with the value 1.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Fifteen to 20 male flies were fixed in 4% PFA in PBST (0.5% Triton X-100) for 2 h and 45 min and subsequently rinsed with 0.5% PBST 4 × 10 min each. Brains were dissected in PBST and blocked in 5% NGS in PBST for 3 h. Primary antibodies were applied overnight at RT. The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-PER (1:1000, provided by R. Stanewsky; Stanewsky et al., 1997), rat anti-TIM (1:1000, provided by J. Giebultowicz), mouse anti-pigment dispersing factor (anti-PDF, 1:2000, DSHB), and chicken anti-GFP (1:1500, Abcam). After rinsing 5 × 10 min each with PBST, secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were applied for 3 h at room temperature. After washing the brains 5 × 10 in PBST, brains were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield mounting medium.

For comparing PER and TIM profiles at LI and HI, CS and clieya;rh61 flies were entrained to the respective light intensity for 5 d and collected around the clock in 2 h intervals. For imaging the dorsal arborizations, CS and rh61 flies were entrained at the standard LD regime and collected at ZT6. To evaluate neuronal activity at LI and HI, pdf-GS>Tric>GFP flies were raised on standard cornmeal medium. Male flies between 2 and 5 d after eclosion were transferred on agar (2% agar, 4% sugar, and 200 μg/ml Ru486) and entrained for 3 d in LD 12:12 at LI and HI, respectively.

All brains were imaged using a Leica SPE or Leica SP5 confocal microscope in 2 μm sections. All settings were kept constant within the experiment. Staining intensity was determined by measuring the brightest 9 pixels of the cell of interest minus 3 different background intensities as described previously (Menegazzi et al., 2013).

Results

HI light delays the evening peak and lengthens the siesta

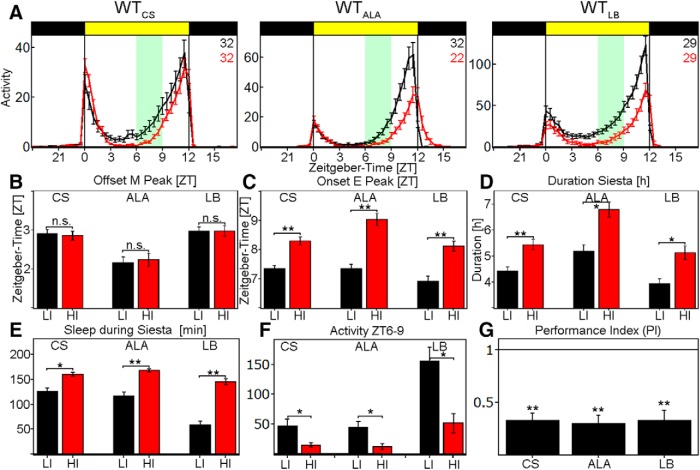

To investigate the effect of light intensity on fly behavior, we subjected three different WT strains to light dark cycles of LI and HI white light. All flies displayed the classic bimodal activity pattern with an M peak and an E peak of activity. These peaks were clearly separated by a siesta, during which flies tend to sleep (Fig. 1A). We did not observe any consistent changes in M- or E-peak amplitude or timing.

Figure 1.

Behavior of WT-flies at LI (black line) and HI (red line). A, Average activity profile of WTCS (left), WTALA (middle), and WTLB (right) at LI (10 lux, black line) and HI (10,000 lux, red line) ± SEM recorded in the Regensburg system. All flies show a bimodal activity pattern with reduced activity during the siesta. B, Quantification of M-peak offset at LI (black) and HI (red) in ZT ± SEM. All strains show a M-peak offset ∼2–3 h after lights on, but do not change the onset upon HI (WTCS: p = 0.9379, WTALA: p = 0.1859, WTLB: p = 0.3862). C, Quantification of E-peak onset at LI (black) and HI (red) in ZT ± SEM. All flies significantly delay the E-peak onset by ∼1 h upon HI simulation (p < 0.0001 for all genotypes). D, Duration of siesta in hours ± SEM. All flies show a significantly longer siesta at HI compared with LI (WTCS: p = 0.0001, WTALA: p = 0.0015, WTLB: p = 0.0012). E, Total sleep amount at LI (black) and HI (red) between ZT6 and ZT9 in minutes ± SEM. All flies significantly increase their sleep amounts at HI (WTCS: p = 0.0014, WTALA: p < 0.0001, WTLB: p < 0.0001). F, Sum of activity indicated in the green area in A. All flies significantly reduce their activity level at HI (WTCS: p = 0.0091, WTALA: p = 0.0114, WTLB: p = 0.0006). G, PI calculated by the sum of activity between ZT6 and ZT9 at HI divided by the sum of activity between ZT6 and ZT9 at LI. All genotypes show a PI significantly <1, which we interpret as a delayed E-peak onset (p < 0.0001 for all genotypes). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

We then considered the shape of the activity profiles. Upon careful inspection, all WT strains appeared to lengthen their siesta by delaying the E-peak onset by 1–2 h, whereas the M-peak offset remained unchanged (Fig. 1B–D). This change in behavior was accompanied by significantly reduced activity levels between ZT6 and ZT9 (green boxes in Fig. 1A,F). We calculated a PI from the activity levels during this period. A PI < 1 represents a reduction of activity at HI, whereas a p > 1 represents an increase. Because the PI is a more objective measurement of the E-peak onset, we focused on this value throughout the study. All WT strains showed a significant reduction of activity, which we interpret as a delayed E-activity onset (Fig. 1G). One explanation for this behavior is that HI induces a longer midday siesta. To address this possibility, we calculated sleep levels in all WT strains. Indeed, HI significantly increased the amount of sleep during the siesta by at least 30 min (Fig. 1E). HI therefore delayed the E activity onset by lengthening the siesta and increasing sleep amounts.

HB eyelets mediate light-intensity integration

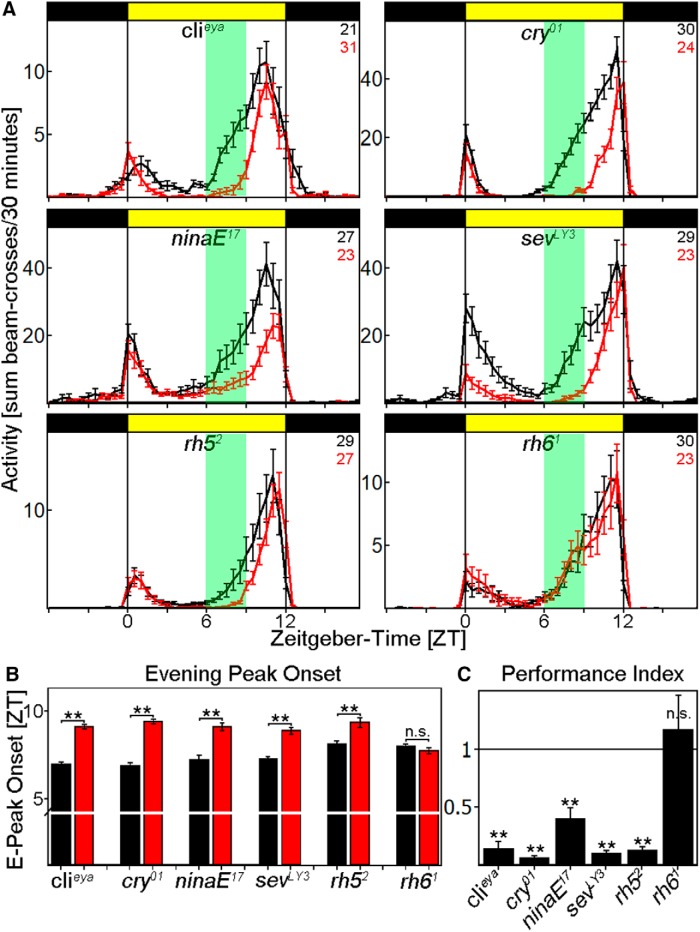

To test which light input pathway mediates this siesta response, we analyzed the behavior of several photoreceptor mutants. Cry01 flies, like WT, showed a bimodal behavior with M and E peaks around lights on or lights off, respectively (Fig. 2A). The mutant strain also responded to HI similarly if not identically to the WT strain: it significantly delayed the onset of E activity (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2B) and showed a PI significantly <1 (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2C). These results suggest that HI responses are not mediated via CRY.

Figure 2.

Behavior of photoreceptor mutants at LI and HI. A, Average activity profiles of flies exposed to LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM using the Regensburg system. Flies deficient of either compound eyes (clieya) or CRY (cry01) behave similar to WTCS, whereas the loss of rhodopsin 6 renders the flies insensitive to light-intensity changes. Consistent with the clieya data, flies affecting the compound eyes (ninaE17, sevLY3, and rh52) behave like WTCS. B, Determination of E-activity onset for all photoreceptor mutants. Clieya, cry01, ninaE17, sevLY3, and rh52 flies significantly delay the onset of the E activity at HI (p < 0.0001), whereas rh61 mutants do not change the timing (p = 0.2885). C, Clieya, cry01, ninaE17, sevLY3, and rh52 flies show a PI significantly <1 (p < 0.0001 for all), whereas the PI of rh61 flies is indistinguishable from 1 (p = 0.5619). **p < 0.001.

We also investigated mutants affecting the fly visual system. We first used the clieya mutant strain to investigate the contribution of the compound eyes for several reasons: (1) the mutant showed no residual eye structures; (2) we previously showed that ocelli and HB eyelets are still intact (Schlichting et al., 2014), and (3) several circadian studies have previously characterized this strain. As in earlier studies, clieya mutants showed a significantly reduced M-peak amplitude, as well as an advanced E peak in both LD conditions (Fig. 2A). A comparison between LI and HI in this strain indicated that HI still exhibits a delay of E activity onset (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2B) and a PI significantly <1 in response to HI (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2C). This suggests that the siesta and E peak phenotypes are independent of the compound eyes.

We then investigated the effect of the HB eyelets. Because the lack of specific drivers precluded manipulating the eyelets without perturbing the compound eyes, we examined the effect of the rh61 mutant. The mutation eliminates the photopigment of the eyelets but also of 70% of R8 in the compound eyes (Sprecher and Desplan, 2008). The mutant exhibited a reduced M-peak amplitude and an advanced E peak under both LI and HI light (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the profiles did not differ between LI and HI light: they neither delayed the onset of E activity (p = 0.2885; Fig. 2B) nor significantly reduced the PI from 1 (p = 0.5619; Fig. 2C).

To verify that the effect is solely visible in rh61 mutant flies, we monitored the behavior of several other rhodopsin mutants under LI and HI conditions: ninaE17, sevLY3, and rh52. They all significantly delayed the E-peak onset (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2A,B) and decreased their activity between ZT6 and ZT9 at HI as WT flies did, resulting in a PI significantly <1 (p < 0.0001).

To exclude the possibility that heating of the flies at HI is the reason for the observed siesta phenotype, we tested nocte flies, which were previously shown to be deficient in temperature entrainment (Glaser and Stanewsky, 2005). As expected, these flies still showed a PI significantly <1 (PI = 0.25 ± 0.06, p < 0.0001), suggesting that light input is the source for the change in behavior (data not shown).

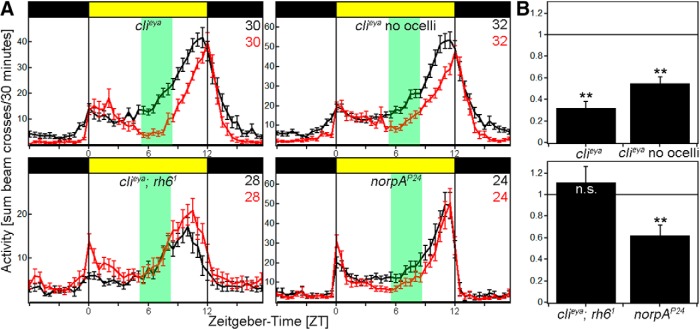

Clieya mutant flies still have working ocelli and HB eyelets. To address the possibility of the ocelli contributing to HI entrainment, we painted the ocelli of clieya mutant flies to eliminate their function. Clieya mutants with painted ocelli showed a significantly delayed E-peak onset and a PI significantly <1 at HI indistinguishably from clieya mutants with functional ocelli (Fig. 3A,B, top). This suggests that the ocelli do not or only marginally contribute to HI entrainment.

Figure 3.

Behavior of photoreceptor mutants at LI and HI. A, Average activity profiles of flies exposed to LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM using the Würzburg system. Flies deficient of either compound eyes (clieya) or compound eyes and ocelli (clieya no ocelli) and flies lacking norpA (norpAP24) still react to HI, whereas the loss of rhodopsin 6 in clieya background renders the flies insensitive to light-intensity changes. B, clieya, clieya no ocelli and norpAP24 flies show a PI significantly <1 (clieya, clieya no ocelli: p < 0.0001, norpAP24: p = 0.0014), whereas the PI of clieya;rh61 is indistinguishable from 1 (p = 0.4613). **p < 0.001.

We further created Clieya;rh61 mutants to eliminate HB eyelet function in clieya background. These flies reproduced the rh61 mutant phenotype: flies showed a reduced M-peak amplitude and an advanced E peak compared with WT flies in both light conditions; they also did not delay their E-peak onset at HI as evident by their PI, which was not different from 1 (Fig. 3A,B, bottom). These data further suggest that the HB eyelet is principally responsible for the adaptation to HI.

Rh6-positive photoreceptors were recently shown to use a norpA-independent phototransduction pathway (Ogueta et al., 2018). To address this issue, we monitored the behavior of norpAP24 flies at LI and HI. These mutant flies had a PI significantly <1 similar to WT flies (Fig. 3A,B, bottom), implicating the newly discovered norpA-independent pathway in the HB eyelets as being involved in mediating the adaptation to HI.

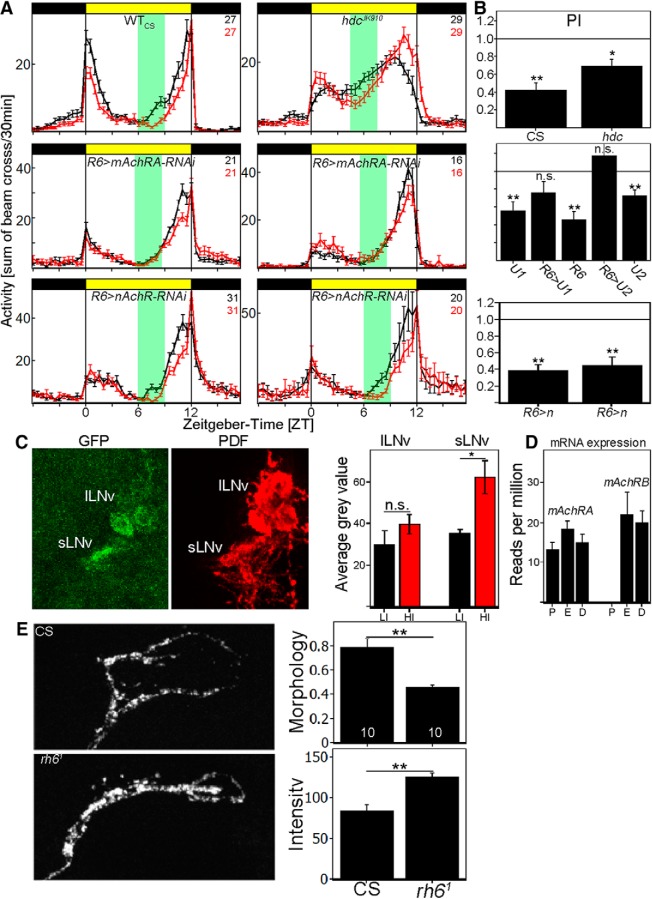

Acetylcholine mediates signal transduction to clock cells

The HB eyelets signal to the s-LNvs via acetylcholine, whereas they appear to signal to the l-LNvs via histamine (Schlichting et al., 2016). We therefore investigated which of these two neurotransmitters transduces light-intensity information to the clock neuron network. As described previously, flies unable to synthesize histamine (hdcJK910) showed a reduced M peak as well as an advanced E peak (Fig. 4A, top), but they also showed a PI significantly <1 (p = 0.0012; Fig. 4B, top); this suggests that histamine is not necessary for siesta adaptation to HI. Because histamine is the only neurotransmitter of the compound eyes (Pollack and Hofbauer, 1991), this agrees with the previous clieya data (Figs. 2A, 3A).

Figure 4.

Cholinergic input to s-LNvs is responsible for HI adaptation. A, Average activity profiles at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM measured in the Würzburg system. Top, Average activity profile of WTCS and the hdcJK910 mutant at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. Flies deficient of histamine synthesis are still reacting to HI by a reduction of activity. Middle, Average activity profiles of mAchRA (BL: 27571; left) and mAchRA (BL:44469) knock-down in sLNvs (right) at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. Knock-down of mAchRA in the sLNvs reproduces rh61-mutant phenotype. The activity profiles do not differ between LI and HI. Bottom, Average activity profiles of 2 independent nAchR (left: BL 28688, right: BL 31883) knock-down in sLNvs at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. Both genotypes show a delayed E-peak onset comparable to the GAL4 control. B, PIs calculated from A. WTCS and hdcJK910 mutants significantly reduce their PI at HI (CS: p < 0.0001, hdc: p = 0.0012). R6-GAL4 and both UAS control flies (U1: BL 27571; U2: BL 44469) show a PI significantly <1 (R6: p < 0.0001, U1: p = 0.0003, U2: p = 0.0002), whereas the PI of mAchRA knock-down in sLNvs is indistinguishable from 1 (R6>U1: p = 0.07134, R6>U2: p = 0.5529). Knock-down of nAchR subunits does not affect HI adaptation and results in significantly reduced PI values (p < 0.0001). C, Brain images of Pdf-GS>Tric-GFP stained against GFP and PDF. GFP expression was measured in s-LNvs and l-LNvs as a correlate for Ca2+ levels in the individual neurons. s-LNvs significantly increase GFP levels at HI, whereas there was no change in l-LNv GFP levels, suggesting an increase of Ca2+ in s-LNvs at HI. D, Relative AChR mRNA expression in PDF (P) cells, evening (E) cells, or DN1s (D). Whereas mAChRA is expressed in all neuron clusters, the PDF cells do not show any mAChRB expression. E, Confocal images of s-LNv dorsal projection in WTCS and rh61 flies at ZT6 HI. WTCS arborizations show a more open conformation compared with rh61 mutants (p = 0.0003), whereas rh61 mutants show a significantly higher staining intensity (p < 0.0001). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

Acetylcholine plays a key role as an excitatory neurotransmitter in mammals and insects and the Drosophila genome encodes 10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits (α1-α7 and β1-β3); subpopulations of these subunits are implicated in Drosophila behavior. In addition, the genome encodes two muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAchRA and mAchRB). To investigate the contribution of these receptors to light-intensity integration, we expressed RNAi constructs against specific receptors or receptor subunits in the s-LNvs with the R6-GAL4 driver.

We tested RNAi lines against two of the 10 existing nAchR subunits (Fig. 4A,B, bottom), and all flies showed a PI < 1 (p < 0.001). In contrast, knocking down mAchRA completely reproduced the behavior of rh61 mutants. Knock-down flies showed a significantly reduced M-peak amplitude and a significantly advanced E peak compared with both parental controls (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained in two independent RNAi lines (Fig. 4A, middle). These data suggest that mAchRA acts in the s-LNvs to integrate cholinergic input. Interestingly, RNA-sequencing data suggest that the s-LNvs are selective: whereas mAChRA is expressed in all circadian subpopulations investigated, only the PDF cells specifically exclude mAchRB expression, indicating an important role of mAchRA in these neurons (Fig. 4D; Abruzzi et al., 2017).

mAchRA is coupled to Gq/11 and interacts with IP3/Ca2+ second messenger pathways (Ren et al., 2015). Because previous dissected brain imaging experiments showed increased Ca2+ in the s-LNvs when the HB eyelets were artificially activated using the P2X2 system (Schlichting et al., 2016), we expressed TRIC-GFP in PDF neurons (Gao et al., 2015), a transcriptional reporter surrogate for Ca2+. To avoid expression during development and express Tric-GFP only in the adult, we used the gene-switch system (pdf-GS-GAL4) and measured GFP intensity in the s- and l-LNvs separately after exposing the flies to LD 12:12 of LI or HI for 3 d. There was no significant difference between LI and HI in the l-LNvs, but a 2-fold increase of GFP in the s-LNvs with HI, suggesting that the eyelets activate the s-LNvs at HI in vivo (Fig. 4C).

An increase in Ca2+ can reflect either an increase in intracellular signaling and/or an increase in neuronal activity. To address neuronal activity, we assayed the s-LNv dorsal projections, which undergo daily oscillations in fasciculation and volume that reflect changes in neuronal activity: they show an open conformation in the early daytime during times of relatively high activity, whereas the conformation is closed at nighttime during times of low activity (Fernández et al., 2008; Sivachenko et al., 2013). We compared the morphology and the staining intensity of these projections between WTCS and rh61 mutant strains in the middle of the day (ZT6), when they normally show an open conformation.

Indeed, the conformation appeared much more closed at ZT6 in rh61 mutants (Fig. 4E). We quantified this phenotype with the complexity index, which represents the number of pixels stained by the PDF antibody divided by the circumference of the stained area; that is, a smaller index reflects a more closed conformation. We found a significantly lower complexity index in the rh61 mutants compared with WT, suggesting that the s-LNvs are less active in the mutant. Consistent with this interpretation, the mutants showed a significantly higher PDF staining intensity at ZT6 in the dorsal projections than the WT. Because neuronal firing is required for neuropeptide release, a higher neuropeptide level in the terminals at ZT6 also suggests less firing in the mutant.

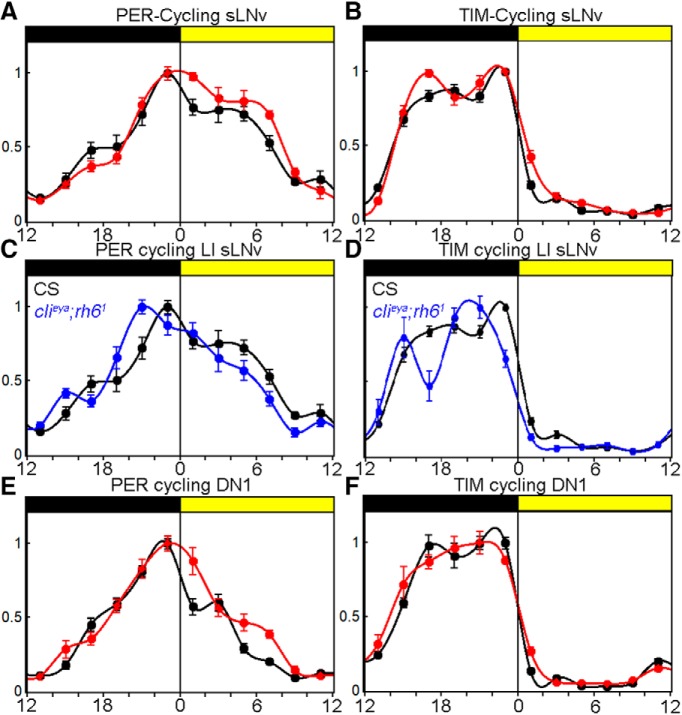

Light input significantly alters PER, but not TIM cycling, in WT s-LNvs

To investigate an effect of light intensity on the molecular circadian clock, we determined PER and TIM levels in clock neurons at 2 h intervals in WT flies under LI and HI conditions. As expected, TIM levels were extremely low during the day, started to accumulate at the beginning of the night, and reached their maximum around ZT20 (Fig. 5B). Also, as expected, PER reached its peak levels toward the end of the night and decayed more slowly than TIM during the day (Fig. 5A). There were no differences in TIM cycling between the two light conditions, most likely due to the extreme light sensitivity of CRY (Vinayak et al., 2013). However, there were significant differences in PER cycling in the s-LNvs: whereas the increase of PER during the night was unaffected, PER disappeared more slowly at HI, suggesting relative PER stabilization during the daytime degradation phase. To address whether this PER stabilization is due to light input from the visual system, we compared WT PER cycling with clieya;rh61 mutants at LI (Fig. 5C). As expected, PER was destabilized during the day compared with WT flies. Most interestingly, PER and TIM staining maxima appear to be advanced by ∼2 h (Fig. 5C), which corresponds to the advanced E-peak timing in the mutant (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that light input from the visual system stabilizes sLNv PER in an intensity-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

HI changes molecular clock synchronization. A, sLNv PER cycling in WTCS at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. PER is stabilized during the daytime at HI. B, sLNv TIM cycling in WTCS at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. TIM cycling is identical in both conditions. C, sLNv PER cycling in WTCS and clieya;rh61 mutants at LI. PER decays faster during daytime and the PER staining intensity maximum is advanced in the mutant. D, sLNv TIM cycling in WTCS and clieya;rh61 mutants at LI. TIM cycling staining intensity maximum is advanced in the mutant. E, DN1 PER cycling in WTCS at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. PER is stabilized during the daytime at HI. F, TIM cycling in WTCS at LI (black line) and HI (red line) ± SEM. TIM cycling is identical in both conditions.

Communication with dorsal neurons mediates the delay in E-peak onset

The s-LNvs were previously shown to be essential for M activity and free run, but their role in governing the timing of the siesta via a delay in E-activity onset is quite unexpected. This suggests that communication of the s-LNvs with downstream partners is necessary for proper siesta control and E-peak adjustment. A recent study showed that the DN1s regulate the siesta via direct inhibition of the E cells (LNds; Guo et al., 2016). In vitro experiments showed that the DN1s react to bath-applied PDF with an increase of neuronal firing and an increase of cAMP, similar to the positive effect of HB eyelet activation on the s-LNvs (Seluzicki et al., 2014). In addition, the s-LNvs send inhibitory PDF signals to the E cells (Liang et al., 2017). Given these strong interactions between the different clock neuron clusters, we expected the same change in PER oscillations in the DN1s such as that shown above for the s-LNvs. Indeed, there is more PER during the day the DN1s at HI (Fig. 5E). Similar to the s-LNvs, TIM staining remains largely unchanged (Fig. 5F). This indicates a HB eyelet to s-LNv to DN1/E cell connection that underlies the HI delay in the E-activity onset.

Discussion

Circadian clocks have evolved as an adaptation to the predictable changes of day and night. To optimally adjust physiology, the clock should be able to assess and respond to several external cues such as temperature, humidity and light. With respect to the latter, the clock can adapt to different levels of irradiance, at least in part to anticipate seasonal changes. Indeed, previous studies showed that the Drosophila clock is extremely light sensitive and can entrain to LD cycles of very low intensity of blue light (Vinayak et al., 2013); this is predominantly due to the photon-integrating function of CRY. In this study, we investigated the role of HI light by simulating LD cycles of 8000–10,000 lux during the day, which is comparable to the light intensity in the shade of a summer day. HI specifically alters the siesta of three WT strains; that is, the duration of the siesta increased by ∼1 h and the flies increased their amount of sleep during the day. This behavioral change was accomplished by a delay in the timing of the E-activity onset, which was accompanied by a PI < 1, which represents a reduction of activity 3–6 h before the E peak at HI compared with LI, which we interpret as a delay in E-activity onset. Because all WTs show a reduction in E-peak amplitude, the PI likely reflects a combination of activity suppression and delayed E-peak onset at HI. However, the PI data correlate well with the manually determined timing of E-activity onset, making it an objective measure for fly behavior.

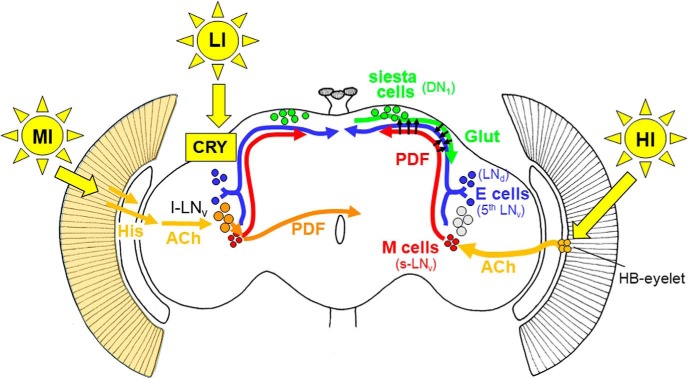

Communication from the s-LNvs is necessary for this response to HI and the neuropeptide PDF is likely to play an essential role. As shown in Figure 6, it is released in the dorsal part of the brain, where PDF activates a subset of dorsal clock neurons (DNs; Seluzicki et al., 2014). In particular, a subset of the DN1s release glutamate in response to stimulation, which directly inhibits the LNds, resulting in an enhanced siesta (Guo et al., 2016). In addition, PDF appears to inhibit the LNds directly (Liang et al., 2017). In any case, the delayed onset of E activity is reproduced by adult-specific silencing of the E cells, suggesting that s-LNv firing and PDF release ultimately affect LNd firing (Guo et al., 2017).

Figure 6.

Model for light input to the circadian clock network of Drosophila. LI light is sensed by CRY in the clock neurons themselves (indicated in the left brain hemisphere) and can quickly reset their oscillations to light (Vinayak et al., 2013). MI light is perceived by the compound eyes, transferred via histamine (His) to the optic lobes and via acetylcholinergic (ACh) interneurons to the large ventrolateral neurons (l-LNv; Muraro and Ceriani, 2015; indicated in the left brain hemisphere). The l-LNv signal via the neuropeptide PDF to the morning (M) and evening (E) cells, respectively (short orange arrow), and to the contralateral hemisphere (long orange arrow). The signaling of HI is shown in the right hemisphere. HI light is perceived by the HB eyelets that signal via ACh to the M cells (s-LNv; Schlichting et al., 2016). The M cells might signal via PDF directly to the E cells (shown by arrows) and inhibit E-cell activity or to the siesta cells (DN1) in the dorsal brain (Guo et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2017). The siesta cells then signal via glutamate (Glut) to the E cells (3 CRY-positive LNd and the fifth sLNv) and delay the onset of E activity (Guo et al., 2016).

In contrast to the CRY-dependent extreme sensitivity of the fly clock to LI light, adaptation to HI light is strictly dependent on the visual system. This result parallels the role of the visual system in adapting fly behavior to natural conditions such as twilight or moonlight (Schlichting et al., 2014, 2015). The compound eyes are clearly involved in synchronizing the clock to a wide range of light intensity and to adapt daily behavior to medium-intensity (MI) light, but by investigating different photoreceptor mutants, we excluded the compound eyes as HI sensors; neither flies lacking the eyes (clieya) nor lacking the important visual system neurotransmitter histamine (hdcJK910) fail to adapt to HI. In contrast, flies lacking Rh6 cannot respond to HI. Because this is the only rhodopsin expressed in the HB eyelets and given that the phenotype is reproduced in the clieya rh61 background, the data indicate that it mediates HI light input to the clock (Sprecher and Desplan, 2008).

The HB eyelets are a major source of visual information in larvae and persist throughout the pupal stage into adulthood. They undergo changes in photopigment (Rh5 to Rh6) as well as in neurotransmitter (ACh to ACh and His) during metamorphosis and are conserved in other fly species such as the blowfly (Sprecher and Desplan, 2008). The HB eyelets directly innervate the adult accessory medulla, which is an important pacemaker center of other insects and contains dendrites of the LNvs in Drosophila (Helfrich-Förster et al., 2002; Malpel et al., 2002).

Previous studies implicated the eyelets in adult entrainment. For example, flies lacking CRY and neurotransmitter output from the entire visual system completely fail to re-entrain to a phase delay of 6 h, whereas functional eyelets alone allows 50% of the flies to re-entrain (Veleri et al., 2007). Similarly, our data here show that flies lacking HB eyelet function cannot delay the E-activity onset in response to HI; this delay may therefore resemble a more traditional circadian phase delay.

It is interesting to contrast these results with mammalian entrainment. Very low irradiance entrainment is predominantly performed by the rods due to their high light sensitivity. The circadian photoreceptor melanopsin functions predominantly at high intensities, which saturate rod and cone signaling (Lall et al., 2010). Here, we show that there are also different pathways for LI and HI light in Drosophila: CRY mediates entrainment to extremely low irradiances, whereas the HB eyelet mediates HI adaptation. This suggests some similarity if not an evolutionary relationship between the HB eyelet and the melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells of mammals.

Another goal of this study was to find the neuronal pathways downstream of the eyelets. In a previous study, we showed that eyelet activation with the P2X2 system leads to increases of Ca2+ and cAMP in the s-LNvs (Schlichting et al., 2016). If this connection is relevant to HI adaptation, then we expected to see Ca2+ increases in the s-LNvs in response to HI. To this end, we used the previously described Tric-GFP tool and showed that s-LNv Ca2+ levels are indeed higher at HI than at LI.

We suggest that this Ca2+ increase reflects increased s-LNv activation by the HB eyelet and HI illumination. This interpretation is buttressed by the fact that rh61 mutants retain a closed conformation of the s-LNv dorsal projections, which is known to reflect relatively low s-LNv activity (Fernández et al., 2008).

s-LNv activation leads to release of neuropeptides/neurotransmitters at its axonal terminals. This also explains the behavioral phenotype of rh61 mutants: as described previously, they show a reduced M-peak amplitude and an advanced E-peak timing (Schlichting et al., 2014). The latter is present even more strongly in the complete loss-of-function pdf01 mutant strain (Renn et al., 1999). This suggests that rh61 mutant phenotype resembles that of a partial PDF loss-of-function; that is, the s-LNvs do not release as much PDF in the dorsal brain as WT flies, as evident by still high PDF staining intensity in the dorsal brain of rh61 mutants in the middle of the day.

Circadian second messengers have previously been implicated in PER expression/stabilization, especially downstream of PDF signaling (Li et al., 2014). We therefore investigated changes of s-LNv PER and TIM cycling in HI versus LI. Whereas TIM expression was not detectably different between the two conditions, PER staining was enhanced and shifted into the daytime by HI, consistent with PER stabilization. This delay of the PER staining profile nicely correlates with the ∼1 h delayed onset of the E activity. The response to HI also fits with observations under long photoperiods: If one compares PER and TIM cycling in LD 12:12 and LD 18:6, only the maximum of PER staining intensity is significantly delayed under long day conditions. The E activity peak is similarly delayed (Menegazzi et al., 2013). Although this suggests that a similar mechanism regulates the integration of light intensity and exposure to long photoperiods, the molecular relationship between the PER cycle and behavior is unknown and awaits further study.

Footnotes

The work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and German Research Foundation (DFG) projects A2 and A1 of the Collaborative Research Center (SFB1047). M.S. was further sponsored by a Hanns–Seidel Excellence Grant sponsored by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and a DFG research scholarship (SCHL2135 1/1). We thank Ralf Stanewsky and Jaga Giebultowicz for providing antibodies and Martin Heisenberg and Claude Desplan for providing fly strains. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grant P40OD018537), were used in this study.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abruzzi KC, Zadina A, Luo W, Wiyanto E, Rahman R, Guo F, Shafer O, Rosbash M (2017) RNA-seq analysis of Drosophila clock and non-clock neurons reveals neuron-specific cycling and novel candidate neuropeptides. PLoS Genet 13:e1006613. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allada R, White NE, So WV, Hall JC, Rosbash M (1998) A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell 93:791–804. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81440-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito J, Houl JH, Roman GW, Hardin PE (2008) The blue-light photoreceptor CRYPTOCHROME is expressed in a subset of circadian oscillator neurons in the Drosophila CNS. J Biol Rhythms 23:296–307. 10.1177/0748730408318588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M (2002) Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 295:1070–1073. 10.1126/science.1067262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini NM, Leiserson WM, Benzer S (1993) The eyes absent gene: genetic control of cell survival and differentiation in the developing Drosophila eye. Cell 72:379–395. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Pichaud F, Sonneville R, Papatsenko D, Desplan C (2003) Distinction between color photoreceptor cell fates is controlled by prospero in Drosophila. Dev Cell 4:853–864. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00156-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daan S, Tinbergen J (1980) Young guillemots (Uria lomvia) leaving arctic breeding cliffs: a daily rhythm in numbers and risk. Ardea 67:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- DeCoursey PJ, Walker JK, Smith SA (2000) A circadian pacemaker in free-living chipmunks: essential for survival? J Comp Physiol A 186:169–180. 10.1007/s003590050017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depetris-Chauvin A, Berni J, Aranovich EJ, Muraro NI, Beckwith EJ, Ceriani MF (2011) Adult-specific electrical silencing of pacemaker neurons uncouples molecular clock from circadian outputs. Curr Biol 21:1783–1793. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezelova E, Dolezel D, Hall JC (2007) Rhythm defects caused by newly engineered null mutations in Drosophila's cryptochrome gene. Genetics 177:329–345. 10.1534/genetics.107.076513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara S, Tsuji K (1980) Entrainment of the circadian activity rhythm to the light cycle: effective light intensity for a zeitgeber in the retinal degenerate C3H mouse and the normal C57BL mouse. Physiol Behav 24:523–527. 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90246-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández MP, Berni J, Ceriani MF (2008) Circadian remodeling of neuronal circuits involved in rhythmic behavior. PLoS Biol 6:e69. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RG, Helfrich-Förster C (2001) The regulation of circadian clocks by light in fruitflies and mice. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356:1779–1789. 10.1098/rstb.2001.0962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XJ, Riabinina O, Li J, Potter CJ, Clandinin TR, Luo L (2015) A transcriptional reporter of intracellular Ca(2+) in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci 18:917–925. 10.1038/nn.4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser FT, Stanewsky R (2005) Temperature synchronization of the Drosophila circadian clock. Curr Biol 15:1352–1363. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE (2010) Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev 90:1063–1102. 10.1152/physrev.00009.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grima B, Chélot E, Xia R, Rouyer F (2004) Morning and evening peaks of activity rely on different clock neurons of the Drosophila brain. Nature 431:869–873. 10.1038/nature02935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Yu J, Jung HJ, Abruzzi KC, Luo W, Griffith LC, Rosbash M (2016) Circadian neuron feedback controls the Drosophila sleep–activity profile. Nature 536:292–297. 10.1038/nature19097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Chen X, Rosbash M (2017) Temporal calcium profiling of specific circadian neurons in freely moving flies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E8780–E8787. 10.1073/pnas.1706608114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin PE, Hall JC, Rosbash M (1990) Feedback of the Drosophila period gene product on circadian cycling of its messenger RNA levels. Nature 343:536–540. 10.1038/343536a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, Berson DM, Yau KW (2002) Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 295:1065–1070. 10.1126/science.1069609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Förster C, Winter C, Hofbauer A, Hall JC, Stanewsky R (2001) The circadian clock of fruit flies is blind after elimination of all known photoreceptors. Neuron 30:249–261. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00277-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Förster C, Edwards T, Yasuyama K, Wisotzki B, Schneuwly S, Stanewsky R, Meinertzhagen IA, Hofbauer A (2002) The extraretinal eyelet of Drosophila: development, ultrastructure, and putative circadian function. J Neurosci 22:9255–9266. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09255.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich-Förster C, Shafer OT, Wülbeck C, Grieshaber E, Rieger D, Taghert P (2007) Development and morphology of the clock-gene-expressing lateral neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol 500:47–70. 10.1002/cne.21146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer A, Buchner E (1989) Does Drosophila have seven eyes? Naturwissenschaften 76:335–336. 10.1007/BF00368438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar JP, Ready DF (1995) Rhodopsin plays an essential structural role in Drosophila photoreceptor development. Development 121:4359–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall GS, Revell VL, Momiji H, Al Enezi J, Altimus CM, Güler AD, Aguilar C, Cameron MA, Allender S, Hankins MW, Lucas RJ (2010) Distinct contributions of rod, cone, and melanopsin photoreceptors to encoding irradiance. Neuron 66:417–428. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Holy TE, Taghert PH (2017) A series of suppressive signals within the Drosophila circadian neural circuit generates sequential daily outputs. Neuron 94:1173–1189.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Guo F, Shen J, Rosbash M (2014) PDF and cAMP enhance PER stability in Drosophila clock neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E1284–E1290. 10.1073/pnas.1402562111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RJ, Lall GS, Allen AE, Brown TM (2012) How rod, cone, and melanopsin photoreceptors come together to enlighten the mammalian circadian clock. Prog Brain Res 199:1–18. 10.1016/B978-0-444-59427-3.00001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpel S, Klarsfeld A, Rouyer F (2002) Larval optic nerve and adult extra-retinal photoreceptors sequentially associate with clock neurons during Drosophila brain development. Development 129:1443–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menegazzi P, Vanin S, Yoshii T, Rieger D, Hermann C, Dusik V, Kyriacou CP, Helfrich-Förster C, Costa R (2013) Drosophila clock neurons under natural conditions. J Biol Rhythms 28:3–14. 10.1177/0748730412471303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraro NI, Ceriani MF (2015) Acetylcholine from visual circuits modulates the activity of arousal neurons in Drosophila. J Neurosci 35:16315–16327. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1571-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogueta M, Hardie RC, Stanewsky R (2018) Non-canonical phototransduction mediates synchronization of the Drosophila melanogaster circadian clock and retinal light responses. Curr Biol 28:1725–1735.e3. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack I, Hofbauer A (1991) Histamine-like immunoreactivity in the visual system and brain of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Tissue Res 266:391–398. 10.1007/BF00318195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren GR, Folke J, Hauser F, Li S, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ (2015) The A- and B-type muscarinic acetylcholine receptors from Drosophila melanogaster couple to different second messenger pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 462:358–364. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renn SC, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, Taghert PH (1999) A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell 99:791–802. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81676-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger D, Stanewsky R, Helfrich-Förster C (2003) Cryptochrome, compound eyes, Hofbauer-Buchner eyelets, and ocelli play different roles in the entrainment and masking pathway of the locomotor activity rhythm in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Rhythms 18:377–391. 10.1177/0748730403256997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutila JE, Suri V, Le M, So WV, Rosbash M, Hall JC (1998) CYCLE is a second bHLH-PAS clock protein essential for circadian rhythmicity and transcription of Drosophila period and timeless. Cell 93:805–814. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81441-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Charles A, Michard-Vanhée C, Alejevski F, Chélot E, Boivin A, Rouyer F (2016) Four of the six Drosophila rhodopsin-expressing photoreceptors can mediate circadian entrainment in low light. J Comp Neurol 524:2828–2844. 10.1002/cne.23994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrelli F, Tauber E, Pegoraro M, Mazzotta G, Cisotto P, Landskron J, Stanewsky R, Piccin A, Rosato E, Zordan M, Costa R, Kyriacou CP (2007) A molecular basis for natural selection at the timeless locus in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 316:1898–1900. 10.1126/science.1138426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting M, Helfrich-Förster C (2015) Photic entrainment in Drosophila assessed by locomotor activity recordings. Methods Enzymol 552:105–123. 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting M, Grebler R, Peschel N, Yoshii T, Helfrich-Förster C (2014) Moonlight detection by Drosophila's endogenous clock depends on multiple photopigments in the compound eyes. J Biol Rhythms 29:75–86. 10.1177/0748730413520428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting M, Grebler R, Menegazzi P, Helfrich-Förster C (2015) Twilight dominates over moonlight in adjusting Drosophila's activity pattern. J Biol Rhythms 30:117–128. 10.1177/0748730415575245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting M, Menegazzi P, Lelito KR, Yao Z, Buhl E, Dalla Benetta E, Bahle A, Denike J, Hodge JJ, Helfrich-Förster C, Shafer OT (2016) A neural network underlying circadian entrainment and photoperiodic adjustment of sleep and activity in Drosophila. J Neurosci 36:9084–9096. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0992-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B, Helfrich-Förster C, Yoshii T (2011) A new ImageJ plug-in “ActogramJ” for chronobiological analyses. J Biol Rhythms 26:464–467. 10.1177/0748730411414264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal A, Price JL, Man B, Young MW (1994) Loss of circadian behavioral rhythms and per RNA oscillations in the Drosophila mutant timeless. Science 263:1603–1606. 10.1126/science.8128246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seluzicki A, Flourakis M, Kula-Eversole E, Zhang L, Kilman V, Allada R (2014) Dual PDF signaling pathways reset clocks via TIMELESS and acutely excite target neurons to control circadian behavior. PLoS Biol 12:e1001810. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Griffith LC, Rosbash M (2008) Light-arousal and circadian photoreception circuits intersect at the large PDF cells of the Drosophila brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:19587–19594. 10.1073/pnas.0809577105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivachenko A, Li Y, Abruzzi KC, Rosbash M (2013) The transcription factor Mef2 links the Drosophila core clock to Fas2, neuronal morphology, and circadian behavior. Neuron 79:281–292. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher SG, Desplan C (2008) Switch of rhodopsin expression in terminally differentiated Drosophila sensory neurons. Nature 454:533–537. 10.1038/nature07062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanewsky R, Frisch B, Brandes C, Hamblen-Coyle MJ, Rosbash M, Hall JC (1997) Temporal and spatial expression patterns of transgenes containing increasing amounts of the Drosophila clock gene period and a lacZ reporter: mapping elements of the PER protein involved in circadian cycling. J Neurosci 17:676–696. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00676.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanewsky R, Kaneko M, Emery P, Beretta B, Wager-Smith K, Kay SA, Rosbash M, Hall JC (1998) The cryb mutation identifies cryptochrome as a circadian photoreceptor in Drosophila. Cell 95:681–692. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81638-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoleru D, Peng Y, Agosto J, Rosbash M (2004) Coupled oscillators control morning and evening locomotor behaviour of Drosophila. Nature 431:862–868. 10.1038/nature02926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veleri S, Rieger D, Helfrich-Förster C, Stanewsky R (2007) Hofbauer-buchner eyelet affects circadian photosensitivity and coordinates TIM and PER expression in Drosophila clock neurons. J Biol Rhythms 22:29–42. 10.1177/0748730406295754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinayak P, Coupar J, Hughes SE, Fozdar P, Kilby J, Garren E, Yoshii T, Hirsh J (2013) Exquisite light sensitivity of Drosophila melanogaster cryptochrome. PLoS Genet 9:e1003615. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Wolf R, Desplan C, Heisenberg M (2008) Motion vision is independent of color in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:4910–4915. 10.1073/pnas.0711484105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii T, Todo T, Wülbeck C, Stanewsky R, Helfrich-Förster C (2008) Cryptochrome is present in the compound eyes and a subset of Drosophila's clock neurons. J Comp Neurol 508:952–966. 10.1002/cne.21702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]