Introduction

Healthcare disparities in quality represent one of the greatest challenges in achieving uniformly high-quality care (1). Research reporting disparities in surgical outcomes are abundant (2–6). The cornerstone of delivering high quality healthcare is ensuring optimal access for all patients. A relative lack of access to surgical services may be a contributing factor to disparities in surgical outcomes.

Access is “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible outcomes” (7). Utilization of services, the process of entering and staying in the system, and the actual quality of care received are all involved. Disparities in access arise when the system disproportionately under-performs for a specific group of patients relative to the historically advantaged population (8, 9). Surgery, because of its time sensitive, often high acuity nature, is greatly dependent on access.

In complex surgical systems, there is no established, methodical way of conceptualizing or measuring disparities in surgical access. Efforts to reduce disparities in surgical access require metrics (standardized measurable indicators), which provide the foundation for focused and tailored interventions, which can be applied broadly. The aims of this systematic review were to identify measures of disparities in surgical access in the US (US), produce a conceptual model for operationalizing them, and build an evidence map of this literature.

This study was a part of the American College of Surgeons’ collaborative effort towards reducing disparities in surgical care - MEASUR (Metrics for Equitable Access and care in SURgery). The overarching mission is to ensure optimal access and equitable healthcare for all surgical patients in every setting across the entire surgical continuum of care. Through research and expert consensus, the MEASUR project, will identify and develop measures that capture disparities in surgical care.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This review was prospectively registered in the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (2018 ID: CRD42018091926). The objective was to identify quantitative measures of surgical access disparities in the US and structure these measures into a novel conceptual model.

We defined a measure as a quantitative primary or secondary study outcome that was assessed across disparity domains (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance status, education, geographic location, and other).

Search criteria

Surgical access disparity measures are ill-defined, therefore a broad search strategy was utilized. An existing literature search strategy was employed using the following terms: healthcare disparities, health status disparities and surgery (3). A PubMed search of publications published between January 2008 and March 2018 was conducted. The date last searched was March 16th, 2018. Reference mining was utilized to identify additional publications.

Eligibility criteria

Included studies incorporated quantitative measures of disparities in surgical access. The definition for surgical access was extrapolated from the NASEM healthcare access definition (7); the timely use of surgical services to achieve the best possible outcomes including the utilization of surgical services, the process of entering and staying in the surgical system, and the quality of care received. The specific measurements of surgical access utilized and the disparity domain (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance status, education, geographic location and other) for which the measures were utilized were extracted. We extracted measures of surgical access disparities, as such, only studies which showed a statistically significant disparity in the specific surgical access measurement were included. This was done as the aim of this literature review was to extract measurable indicators in areas where significant disparities in surgical access were identified, these measurable indicators have the potential to be converted into disparity sensitive surgical access metrics. Studies were excluded if they were not written in English or not conducted in the US.

Data extraction and analysis

The individual measures of surgical access disparities were extracted from each study. Two investigators screened the articles and extracted the measures (EdJ and MG). For each measure, the reported disparity group was identified (racial/ethnic, education, insurance, income, geography and other). The measures were classified into surgical specialties by the 14 subspecialties defined by the American College of Surgeons; general, thoracic, colon and rectal, obstetrics and gynecology, gynecology oncology, neurology, ophthalmic, oral maxillofacial, orthopedic, otolaryngology, pediatric, plastic maxillofacial, urology and vascular.

Measures were categorized per a conceptual model derived from the Alkire et al, 2016 Global Access to Surgical Care model (10). The conceptual model was reviewed and refined in biweekly MEASUR project meetings with input from members of the American College of Surgeons, National Quality Forum, Eastern Virginia Medical School and the University of California—Los Angeles.

Measures were graphed on an evidence map; a systematic approach to evidence synthesis to represent gaps in knowledge and interpret individual studies within the context of a global knowledge on disparities to highlight future research needs (11). The evidence map illustrates the number of measures by surgical access domain (y-axis), surgical specialty (x-axis), disparity domain (color) and number of studies reporting disparities for each measure (diameter of the markers). This map depicts the landscape of evidence describing measures of surgical access disparities. Insights and findings from this map was derived through observation and discussion among co-authors and MEASUR project co-investigators.

Results

Search results

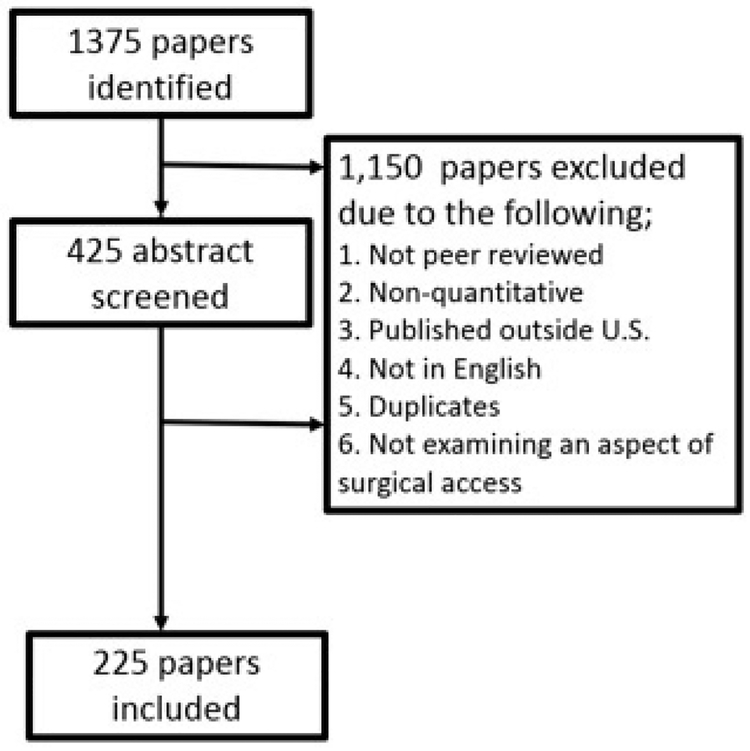

The search returned 1,375 original articles. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 225 studies were included. From these studies, 223 measures of surgical access were extracted (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of studies for inclusion in a systematic literature review of measures of surgical access in the US.

Conceptual Model of Surgical Access Disparities

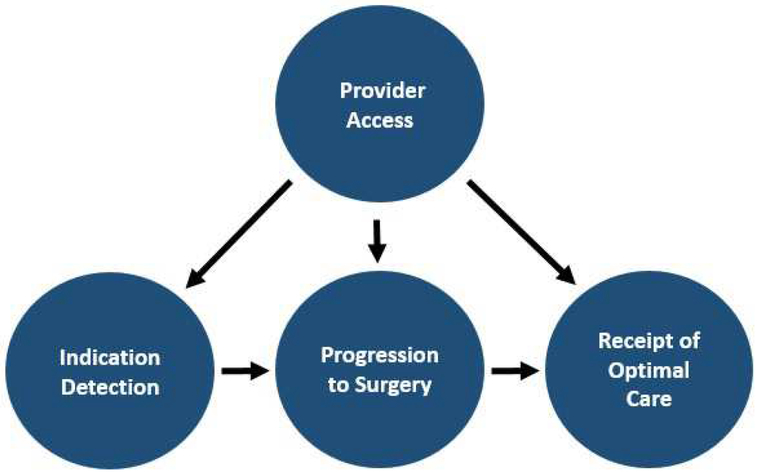

Measures were classified based on the following categories: Provider Access, Surgical Indication Detection, Progression to Surgery and Receipt of Optimal Care (Fig 2). The unidirectional arrows in the diagram suggest how each of the categories sequentially influences other categories.

Fig 2.

A conceptual model for classifying surgical access disparity measures in the US.

Provider Access

Provider access measures reflect disparities in access to the highest quality of surgical care and discharge provider facilities. A total of 30 provider access measures were identified (Table 1). Measures showed disparities in the use of low-volume hospitals, low-volume surgical practitioners, the use of safety net hospitals, and the use of hospitals with a higher risk-adjusted surgical mortality. Key examples are described. One measure reported access disparities to a Level I or II trauma center within 60 minutes via an ambulance or helicopter (12). Three measures examined disparities in optimal discharge disposition to indicated rehabilitation facilities for trauma (13), cardiac surgery (14) and traumatic brain injury patients (15–17).

Table 1:

Provider Access Measures of Surgical Access Disparities

| Measure | Disparity group examined | Surgical specialty |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical access disparity | ||

| Proportion of patients with traumatic brain injury discharged to rehabilitation, long term acute care or nursing facilities | Racial/ethnic (15–17); insurance (15, 17) |

Neurological |

| Proportion of patients receiving trauma care who are discharged to an inpatient rehab facility | Other- undocumented immigrants(13) | General |

| Proportion of patients who are referred to cardiac rehabilitation post percutaneous intervention or cardiac surgery | Other- hospital specific (14) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients with access to a level 1 or 2 trauma center within 60 minutes via ambulance or helicopter | Income (12); geography (12); insurance (12) |

General |

| Disparity in the use of low volume hospitals/ low volume surgeon/safety net hospital use/hospital use with higher risk adjusted mortality | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma liver surgeries | Racial/ethnic (93); income (93); education (93) |

General |

| Pancreatic cancer resection | Racial/ethnic (94) | General |

| Knee arthroplasty | Racial/ethnic (95) | Orthopedic |

| Total hip replacement | Racial/ethnic (96) | Orthopedic |

| Thyroidectomy | Racial/ethnic (97, 98); Insurance (98); income (98) |

General |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | Racial/ethnic (99) (100) | Thoracic |

| Adrenal operation | Racial/ethnic (101) | General |

| Endocrine surgery | Racial/ethnic (92); other - high health risk communities (92) |

General |

| Receiving radical prostatectomy at center offering robot-assisted radical prostatectomy | Racial/ethnic (102); income (102); insurance (102) |

Urology |

| Localized prostate cancer treatment by high volume urologist | Racial/ethnic (103) | Urology |

| Diagnosis by low volume and change to high volume for prostate cancer treatment | Racial/ethnic (103) | Urology |

| Colorectal cancer care | Racial/ethnic(104); insurance (104) |

Colon & rectal |

| Trauma surgery | Racial/ethnic(105) | General |

| Carotid endarterectomy | Racial/ethnic(41) | Vascular |

| Critical limb ischemia amputation or revascularization | Racial/ethnic (106); income (106); insurance (106) |

Vascular |

| Breast cancer resection for patients aged >65years | Racial/ethnic (75) | General |

| Pediatric neurooncological surgery | Racial/ethnic(107, 108); income (107) |

General |

| Brain tumor craniotomy | Racial/ethnic (42); insurance (42) |

Neurological |

| Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, coronary artery bypass grafting, angioplasty, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, carotid endarterectomy, total hip replacement | Racial/ethnic (72) | General |

| Esophageal, pancreatic and colorectal cancer procedure | Racial/ethnic (109); insurance (109) |

General |

| Ovarian cancer surgical care | Racial/ethnic (110, 111) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Endometrial/uterine cancer | Racial/ethnic (112, 113) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Benign prostatic hypertrophy treatment access to hospitals offering laser prostatectomy | Income (114) | Urology |

| Scoliosis surgical procedure | Racial/ethnic (115) | Orthopedic |

| Grouped oncology- colectomy, cystectomy, esophagectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, lung resection, pancreatectomy, prostatectomy | Racial/ethnic (116); income (116); insurance (116) |

General |

| Acute ischemic stroke admission to hospitals performing mechanical thrombectomy at high volume | Racial/ethnic (117); income (117); insurance (117) |

Neurological |

Surgical Indication Detection

Surgical indication detection measures represent disparities in the time of diagnosis, presentation or referral (detection) of a potential surgical condition (indication). There were 39 measures identified (Table 2). Twenty-one measures described a more advanced stage of cancer at the time of diagnosis including breast (18–22), lung (23), rectal (24), hepatocellular carcinoma (25) and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (26). Fourteen measures examined more advanced clinical presentations of conditions (meaning non-cancer). Examples of advanced clinical presentations include the severity (patency) of peripheral arterial disease at presentation (27–31), the time from onset of pediatric abdominal pain to presentation for appendicitis (32) and pain intensity or wellbeing scores for patients undergoing knee replacements for osteoarthritis (33).

Table 2:

Surgical Indication Detection Measures of Surgical Access Disparities

| Measure of surgical access disparity | Disparity group examined | Surgical specialty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of diagnosis for pediatric patients aged ≤ 21 diagnosed with primary sarcomas | Racial/ethnic (118) | Pediatric | |

| Stage of diagnosis for pediatric patients diagnosed with well differentiated thyroid cancer | Income (119); education (119); insurance (119) |

Pediatric | |

| Stage at diagnosis of pediatric patients aged ≤ 10 years diagnosed with melanoma | Racial/ethnic (120) | Pediatric | |

| Stage at presentation of pediatric patients aged ≤ 18 years diagnosed with primary central nervous system tumors | Racial/ethnic (121) | Pediatric | |

| Stage of diagnosis for patients diagnosed with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | Racial/ethnic (26) | Pediatric | |

| Stage of diagnosis at presentation of patients diagnosed with adenocarcinomas | Racial/ethnic (122); geography (122) |

General | |

| Stage of diagnosis for patients diagnosed with rectal cancer | Insurance (24) | Colon & rectal | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with endometrial cancer | Racial/ethnic (112, 123, 124) | Gynecologic oncology | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with cervical cancer | Insurance (125); racial/ethnic (126, 127) |

Gynecologic oncology | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with breast, prostate or colorectal cancer | Income (128) education (128) |

General | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with breast cancer (female) | Racial/ethnic (18, 19); income (18–20); geography (20) ; insurance (21) |

General | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with breast cancer (male) | Income (22) | General | |

| Proportion of patients with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis of small bowel carcinoid tumor | Racial/ethnic (129) | General | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with soft tissue sarcoma (in the extremity) | Racial/ethnic (130) | Orthopedic | |

| Proportion of patients with well differentiated thyroid cancer detected incidentally on unrelated imaging | Insurance (131) | General | |

| Stage of tumor disease severity at presentation for patients with brain tumors | Racial/ethnic (42); insurance (42) |

Neurological | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma | Racial/ethnic (25); insurance (25) |

General | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with lung cancer | Racial/ethnic (23) | Thoracic | |

| Stage at diagnosis of patients with vestibular schwannoma | Racial/ethnic (132) | Neurological | |

| Later stage of diagnosis for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer measured by prostate specific antigen (psa) level or gleason scores | Racial/ethnic (133) | Urology | |

| Proportion of patients with chronic venous insufficiency presenting with advanced disease requiring ulcer debridement | Racial/ethnic (134) | Vascular | |

| Clinical severity score in venous insufficiency patients presenting for radiofrequency ablation | Racial/ethnic (135) | Vascular | |

| Proportion of patients with peripheral artery disease presenting with critical limb ischemia | Racial/ethnic (136) | Vascular | |

| Proportion of peripheral artery disease presenting with critical limb ischemia who undergo a revascularization attempt (limb salvage) vs amputation | Racial/ethnic (27, 137) | Vascular | |

| Severity of patients with peripheral artery disease at presentation (patency) | Racial/ethnic (27–29); insurance (28, 29, 31); income (29, 30) |

Vascular | |

| Rate of limb salvage in patients presenting with advanced peripheral arterial disease | Racial/ethnic (27, 29, 138); insurance (29, 31); income (29, 30) |

Vascular | |

| Proportion of patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis | Insurance (139) ; racial/ethnic (139) |

Vascular | |

| Age at first presentation of patients presenting with pediatric nonsyndromic craniosynotosis | Racial/ethnic (140) | Pediatric | |

| Age at first surgical intervention for patients presenting with pediatric nonsyndromic craniosynotosis | Insurance (141); racial/ethnic (141) |

Pediatric | |

| Proportion of pediatric patients with perforated appendicitis | Racial/ethnic (32, 46); income (32, 46); Insurance (32) |

Pediatric | |

| Proportion of pediatric appendicitis patients experiencing symptoms > 48 hours before surgical presentation | Racial/ethnic (32) | General | |

| Proportion of patients with perforated appendicitis | Insurance (142) | General | |

| Pre-operative knee replacement wellbeing scale | Racial/ethnic (33) | Orthopedic | |

| Pre-operative knee replacement pain intensity scale | Racial/ethnic (33) | Orthopedic | |

| Complexity score of presenting problems at a tertiary care hand surgery facility (higher) | Insurance (143) | Orthopedic | |

Progression to Surgery

Progression to surgery measures reflect disparities in the process of attaining a surgical opinion or procedure once a surgical indication has been detected. One hundred measures describing progression to surgery were identified (Table 3). Four measures examined disparities in persons for whom surgery was indicated being offered a surgical option for conditions like pelvic organ prolapse (34), loco-regional pancreatic cancer (35), or pediatric sensorineural hearing loss (36). Thirty-six measures examined disparities in persons with a potential surgical indication receiving the indicated surgical procedure (decision to treat) for cancer, vascular, orthopedic, cardiac, neurosurgery, otolaryngology, and bariatric surgery. Twelve measures examined disparities in the total surgical rates per population for surgeries like joint replacements (37–39), elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (40), or carotid endarterectomies (41). Five measures examined disparities in the emergency-to-elective procedure ratios for conditions in which an elective procedure may have prevented a later emergency procedure, like abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (40) or brain tumor craniotomies (42). Disparities in the time between surgical indication detection and the surgical evaluation or procedure were examined by eight measures. Examples of this include the time between a breast cancer biopsy to surgery (43–45), the time between presentation of pediatric abdominal pain to undergoing appendectomy (46) and the interval between sonographic detection of carotid stenosis warranting carotid endarterectomy and the procedure (47).

Table 3:

Progression to surgery measures of surgical access disparities.

| Measure of surgical access disparity | Disparity group examined | Surgical specialty |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of women with pelvic organ prolapse offered a surgical option | Income (34); insurance (34) |

Obstetrics & gynecology |

| Proportion of patients with advanced knee/hip replacement being recommended for a total joint replacement | Racial/ethnic (144) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with sensorineural hearing loss meeting the audiology criteria for cochlear implantation receiving pediatric cochlear implant referral | Insurance (36); other -married parents (36) |

Otolaryngology |

| Proportion of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving a surgical referral | Geography (145); insurance (145) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer receiving a surgical consult or evaluation | Racial/ethnic (35) | General |

| Cumulative proportion of patients with breast, prostate, lung or colorectal cancer, who undergo indicated surgical treatment | Income (128); education (128) |

General |

| Cumulative proportion of patients who receive indicated first course directed surgery for breast, prostate, lung, uterine, cervix, ovarian, melanoma, urinary bladder and colorectal cancer | Racial/ethnic (146) | General |

| Proportion of patients who receive all indicated treatment for breast, prostate, lung, uterine, cervix, upper gi, head & neck cancer, hodgkin lymphoma and diffuse b cell lymphoma | Other -hiv patients (147) | General |

| Proportion of patients who undergo indicated pancreatic cancer surgical resection | Insurance (90, 122); racial/ethnic (35, 122); Geography (122) |

General |

| Proportion of patients who undergo indicated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor surgical resection | Racial/ethnic (26) | General |

| Proportion of patients who undergo indicated pancreatic adenocarcinoma surgical resection | Racial/ethnic (148) ; income(149) |

General |

| Proportion of patients who undergo indicated surgery for uterine grade iii endometrial adenocarcinoma, carcinosarcoma, clear cell carcinoma & papillary serous carcinoma | Racial/ethnic (123) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients who undergo definitive surgery for high grade endometrial cancer | Racial/ethnic (150) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients who undergo definitive surgery for cervical cancer | Insurance (125) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients who undergo stage adjusted surgery for cervical cancer | Racial/ethnic (127) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients who undergo indicated prostate cancer resection | Racial/ethnic (133, 151); insurance (151); income (151) |

Urology |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection for lung cancer | Racial/ethnic (59, 152) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of stage adjusted patients undergoing surgical resection for lung cancer | Racial/ethnic (59) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for localized non-small cell lung cancer | Racial/ethnic (153, 154) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection for stage i and ii non small cell lung cancer within 6 weeks of diagnosis | Racial/ethnic (155) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection, chemotherapy or radiation for stage iii non small cell lung cancer within 6 weeks of diagnosis | Racial/ethnic (155) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection for stage i and ii non small cell lung cancer | Racial/ethnic (156) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients with lung cancer receiving the ‘standard’ therapy | Insurance (157) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection for breast cancer | Income (20, 73); geography (20) ; racial/ethnic (43, 73) |

General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgical resection for non-metastatic breast cancer | Racial/ethnic (74) | General |

| Proportion of patients aged over 65 years who receive primary surgical treatment (mastectomy or breast conserving surgery) for stage i and ii breast cancer | Racial/ethnic (75) | General |

| Proportion of patients who receive stage specific treatment for breast cancer | Insurance (71) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer | Racial/ethnic (73); income (73); Insurance (158) |

Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of patients undergoing definitive surgery for rectal cancer | Insurance (24) | Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of patients older than 80 years undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer | Racial/ethnic (159) | Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of hiv patients who receive indicated cancer treatment for cumulative solid tumor and lymphoma | Racial/ethnic (147); insurance (147) |

General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing debulking surgery for ovarian cancer | Income (160) | Obstetrics & gynecology |

| Proportion surgery for ovarian cancer | Racial/ethnic (160, 161) | Obstetrics & gynecology |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities | Racial/ethnic (130) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing hepatectomy or ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma | Racial/ethnic (162) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing esophagectomoy for esophageal cancer | Racial/ethnic (163) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for vestibular schwannomas | Racial/ethnic (132) | Neurological |

| Proportion of patients with peripheral arterial disease meeting vascular lab criteria for procedural intervention receiving the intervention (angioplasty, stenting, endarterectomy or bypass grafting) | Racial/ethnic (79) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients with carotid artery disease meeting vascular lab criteria for intervention undergoing a procedure [carotid end arterectomy or stenting] | Racial/ethnic (79) insurance (164) |

Vascular |

| Proportion of patients undergoing procedure when admitted for a traumatic brain injury | Insurance (15) | Neurological |

| Proportion of patients undergoing mechanical revascularization procedures after acute ischemic stroke | Racial/ethnic (117); income (117); insurance (117) |

Neurological |

| Proportion of elderly patients with arteriovenous fistulas among hemodialysis patients | Racial/ethnic (165) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients undergoing total joint replacement for advanced knee/hip osteoarthritis | Racial/ethnic (144, 166); income (166) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing knee replacement for knee osteoarthritis | Education (167); insurance (167) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing hip replacement for hip osteoarthritis | Education (167); insurance (167) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with scoliosis undergoing surgical intervention | Insurance (115); racial/ethnic (115) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation | Racial/ethnic (168); insurance (168) |

Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing a procedure (angiogram, per cutaneous intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting) during/after acute myocardial infarction admission | Racial/ethnic (169); sex (169) |

Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing coronary revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention) after myocardial infarction | Racial/ethnic (170); education (170); insurance (170) |

Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis | Racial/ethnic (171) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients declining indicated aortic valve replacement recommendation for severe aortic stenosis | Racial/ethnic (171) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients receiving indicated bariatric surgery | Racial/ethnic (172, 173); geography (172); income (173, 174); insurance (173) |

General |

| Proportion of patients receiving bariatric surgery, laparoscopic gastric bypass, when indicated | Racial/ethnic (175) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing tympanostomy tube placement for otitis media | Racial/ethnic (176) | Otolaryngology |

| Proportion of medicare patients undergoing deep brain simulation surgery for parkinson’s disease | Racial/ethnic (177); income (177) |

Neurological |

| Time between diagnosis of pediatric well-differentiated thyroid cancer to intervention | Income (119); insurance (119) |

General |

| Time between diagnosis of gynecological malignancy to surgery | Other - public vs. Private hospital (178) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Time between presentation of pediatric abdominal pain to appendectomy | Racial/ethnic (46); income (46) |

Pediatric |

| Time between diagnosis via sonogram of carotid stenosis warranting carotid endarterectomy and carotid endarterectomy receipt | Racial/ethnic (47) | Vascular |

| Time between clinical presentation of ureteropelvic junction obstruction to urology evaluation/pyeloplasty | Racial/ethnic (179) | Urology |

| Time between abnormal imaging or core biopsy to surgery for breast cancer patients | Racial/ethnic (43–45); insurance (44) |

General |

| Time from polysomnography test recommending adenotonsilectomy for children with sleep disordered breathing to receipt of adenotonsilectomy among pediatric patients | Insurance (180) | Otolaryngology |

| Proportion of adults undergoing knee arthroplasty | Racial/ethnic (37, 38) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of adults over 65 undergoing knee/hip arthroplasty | Racial/ethnic (39) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with peripheral vascular disease receiving lower extremity amputation | Racial/ethnic (181) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients undergoing an elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair per population | Racial/ethnic (40) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients receiving a thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair per population | Racial/ethnic (182) | Vascular |

| Proportion of people receiving stress urinary incontinence surgery per population | Racial/ethnic (183) | Vascular |

| Proportion of people receiving carotid endarterectomy per population | Racial/ethnic (41) | Vascular |

| Outpatient surgery volume per population | Racial/ethnic (184) | General |

| Number of general surgeons per population | Racial/ethnic (184) | General |

| Number of carotid endarterectomy, lumbar spine fusion, knee replacement, aa repair, prostatectomy, hip replacement, aortic valve repair, open & internal fixation of the femur and appendectomy procedures per population | Geography (185) | General |

| Number of laparoscopic appendectomy procedures per population | Racial/ethnic (186); income (186) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with diabetes hospitalized for diabetes-related cardiovascular disease who receive a cardiac procedure (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting) | Racial/ethnic (187) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing angiography and revascularization procedures after myocardial infarction | Racial/ethnic (188); income (188) |

Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients with lumbar spine stenosis who undergo surgery | Racial/ethnic (189) | Orthopedic |

| Ratio of emergency to elective gastrointestinal procedures among pediatric patients | Racial/ethnic (190) | Pediatric |

| Ratio of emergency to elective abdominal aortic aneurysm procedures | Racial/ethnic (40) | Vascular |

| Ratio of emergency to elective thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm procedures | Racial/ethnic (191) | Vascular |

| Ratio of emergency to elective craniectomy procedures for brain tumors | Racial/ethnic (42); insurance (42) |

Neurological |

| Ratio of cumulative emergency to elective biliary, hernia and colorectal operations | Racial/ethnic (192) | General |

| Proportion of patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma who receive a liver transplant | Racial/ethnic (25, 162, 193–195); Insurance (25, 193, 194) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving surgery (local ablation or a liver transplant) | Income (162); insurance (162) |

General |

| Proportion of patients not listed on hepatocellular carcinoma liver transplant list for non-medical reasons | Insurance (194); racial/ethnic (194) |

General |

| Proportion of patients placed on the liver transplant list for end stage liver disease | Education (196); insurance (196); racial/ethnic (196) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with end stage liver disease referred to a transplant center | Racial/ethnic (196) | General |

| Proportion of patients who attend a transplant center if referred for end stage liver disease | Racial/ethnic (196) | General |

| Higher model for end-stage liver disease (meld) score on liver transplant waitlist | Racial/ethnic (197) | General |

| Proportion of patients receiving a liver transplant within 3 years of being listed | Racial/ethnic (197) | General |

| Higher model for end-stage liver disease (meld) score at presentation to a liver transplant center | Racial/ethnic (198) | General |

| Proportion of patients referred early for liver transplant evaluation | Racial/ethnic (198) | General |

| Proportion of patients on the active renal transplant waitlist | Other- linguistic isolation (199) | General |

| Proportion of patients who are referred for a renal transplant | Income (91) | General |

| Proportion of patients who die whilst on renal transplant waitlist | Income (200) | General |

| Proportion of patients on the renal transplant waitlist who received a renal transplant | Income (200) ; racial/ethnic (201) |

General |

| Proportion of patients who attend/present to their first renal transplant evaluation appointment | Racial/ethnic (201) | General |

| Proportion of patients on the renal transplant waitlist who are inactive due to loss of follow up | Racial/ethnic (201) | General |

| Median time from transplant referral to decreased donor transplant | Racial/ethnic (201) | General |

| Time from a patient starting renal dialysis to being placed on the renal transplant waitlist | Insurance (202); income (202); racial/ethnic (202) |

General |

| Proportion of patients who receive a preemptive (pre-dialysis initiation) decreased donor renal transplant | Insurance (203); racial/ethnic (203) |

General |

| Proportion of patients who receive assessment for renal transplantation | Insurance (204); racial/ethnic (204) |

General |

| Proportion of pediatrics patients who receive a preemptive renal live donor transplant | Racial/ethnic (205) | General |

| Proportion of patients with cystic fibrosis who are accepted onto the lung transplant waitlist after their first lung transplant evaluation | Insurance (206); education (206); income (206) |

General |

Receipt of Optimal Care

Receipt of optimal care measures reflect disparities in a patient’s ability to receive the highest quality surgical care. A total of 54 measures examined optimal care disparities, 37 examined surgical care and 14 examined postoperative follow up care (Table 4). These measures included disparities in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction (48–57), the recommended number of lymph nodes removed for conditions like gastric cancer (58) or lung cancer (59), immediate versus delayed cholecystectomy rates (60), and amputation rates for lower extremity open fractures (61). Fifteen measures examined disparities in the utilization of minimally invasive procedures such as laparoscopic appendectomies (62), hysterectomies (63, 64) or cholecystectomies (65), as well as breast-conserving surgery versus mastectomies (18, 19, 21, 66–68). Optimal postoperative follow-up measures examined disparities in emergency stoma reversal rates (69), rates of breast-conserving surgery without receipt of full radiotherapy (43), or failure to complete internal fixation removal for cases of pediatric femoral shaft fractures (70).

Table 4:

Receipt of Optimal Care Measures of Surgical Access Disparities

| Measure of surgical access disparity | Disparity group examined | Surgical specialty |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of early-stage, unilateral breast cancer patients receiving breast reconstruction after mastectomy | Racial/ethnic (48–56); insurance (48, 50, 52, 54–56) ; geography (48, 57); income (50, 54); education (50, 51) |

General |

| Proportion of patients receiving breast reconstruction during the same hospitalization (i.e. immediately) after mastectomy | Insurance (152, 207); racial/ethnic (77, 78); income (77); education (77) |

General |

| Proportion of stage 0 to ii unilateral breast cancer patients receiving contralateral prophylactic mastectomy | Racial/ethnic (208) | General |

| Ratio of mastectomies performed in outpatient vs. Inpatient settings | Racial/ethnic (209) | General |

| Proportion of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who undergo bridging locoregional therapy among all patients who receive an orthotropic liver transplant | Racial/ethnic (210); education (210); insurance (210) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with soft tissue sarcoma who receive limb sparing surgery | Racial/ethnic (211, 212) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with ovarian cancer undergoing bowel resection, peritoneal biopsy/omentectomy | Racial/ethnic (111) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of gastric cancer patients with surgically treated gi malignancy receiving “adequate lymphadenectomy” (more than 15 esophagus, 15 stomach, 12 small bowel, 12 colon, 12 rectum, and 15 pancreas) | Income (58) | General |

| Proportion of lung cancer patients receiving appropriate lymph node resection | Racial/ethnic (59) | Thoracic |

| Stage-adjusted proportion of lung cancer patients receiving appropriate lymph node resection | Racial/ethnic (59) | Thoracic |

| Proportion of ovarian cancer patients who have the recommended number of lymph nodes removed | Racial/ethnic (111) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of breast cancer patients who have the recommended number of lymph nodes removed | Racial/ethnic (76) | General |

| Proportion of patients with gastric cancer who have the recommended number of lymph nodes removed | Insurance (213) | General |

| Proportion of patients localized/regional prostate cancer who have the recommended number of lymph nodes removed | Racial/ethnic (214) | Urology |

| Proportion of pediatric patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain who received abdominal ct imaging to confirm appendicitis | Racial/ethnic (46) ; insurance (46) |

General |

| Proportion of patients with end-stage renal disease who have an arteriovenous fistula at initial hemodialysis | Racial/ethnic (215) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients with acute cholecystitis who receive immediate cholecystectomy | Insurance (60) ; racial/ethnic (60) |

General |

| Proportion of all patients admitted for acute ischemic stroke who receive reperfusion on the first admission day, invasive angiography, and operative procedures including carotid endarterectomy | Income (216) | Neurological |

| Proportion of all carotid endarterectomy surgeries with inappropriate clinical indicators (high comorbidity in asymptomatic patient, operating in a setting of a recent or severe disabling stroke, minimal stenosis, operating contralateral to symptoms, occluded artery) | Racial/ethnic (41) | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients with lower extremity fractures (open tibial/fibular and femoral fractures) who undergo amputations | Racial/ethnic (61) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with graves’ disease who receive a thyroidectomy | Income (217) | General |

| Proportion of patients presenting with blunt injuries with pelvic fractures who receive diagnostic procedures (vascular ultrasound, ct of the abdomen), transfusions, venous pressure monitoring, and arterial catheterization for embolization | Insurance (218) | General |

| Proportion of patients with symptomatic heart failure who receive biventricular pacing | Racial/ethnic (219); income (219); insurance (219) |

Thoracic |

| Proportion of patients undergoing major elective orthopedic surgery who receive autologous blood transfusion | Insurance (220); income (220); racial/ethnic (220) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients receiving laparoscopic vs. Open hysterectomies | Racial/ethnic (63) | Obstetrics & gynecology |

| Proportion of patients receiving laparoscopic vs. Open hysterectomies for the indication of fibroids | Racial/ethnic (64) | Obstetrics & gynecology |

| Proportion of patients receiving laparoscopic vs. Open hysterectomy for uterine cancer | Racial/ethnic (113) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of breast cancer patients who receive breast conservation surgery vs. Mastectomy | Insurance (18, 21); racial/ethnic (19, 66, 67); income (66, 68) |

General |

| Proportion of cumulative open vs. Laparoscopic rates of cumulative colorectal surgery for colorectal cancer, diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease and benign colorectal tumors | Racial/ethnic (221) | Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer who have laparoscopic vs. Open surgery | Income (222) ; insurance (222, 223); geography (223) |

Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of patients undergoing surgery for ulcerative colitis open vs. Laparoscopic surgery | Insurance (224) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing a laparoscopic vs. Open surgery appendectomy, gastric fundoplication or gastric bypass | Racial/ethnic (62) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing acute surgery, minimally invasive vs. Open for appendectomy or cholecystectomy | Racial/ethnic (65); insurance (65) |

General |

| Rates of laparoscopic vs. Open appendectomies for patients ages between 11 and 18. | Racial/ethnic (225) | Pediatric |

| Proportion of patients undergoing an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair via endovascular vs. Open surgery | Racial/ethnic (226, 227); insurance (226) |

Vascular |

| Proportion of patients undergoing a thoracic aortic repair via thoracic endovascular aortic repair vs. Open surgery | Racial/ethnic (228); | Vascular |

| Proportion of patients presenting with critical limb ischemia from peripheral arterial disease undergoing endovascular or open revascularization vs. Amputation | Racial/ethnic (106, 229); income (106); insurance (106) |

Vascular |

| Proportion of patients receiving a non-traumatic amputation as the transfermoral compared to transtibial position | Income (230); insurance (230); Other- sex (230) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with choledocholithiasis receiving ercp vs. Common bile duct exploration | Geography (231) | General |

| Proportion of patients undergoing a radical prostatectomy vs. A minimally invasive radical prostatectomy | Racial/ethnic (232) | Urology |

| Proportion of patients who underwent a breast conserving surgery for breast cancer completing the recommended length of radiation | Insurance (18) ; racial/ethnic (43) |

General |

| Proportion of patients post mastectomy for local-regionally advanced breast cancer receiving local radiotherapy | Geography (233) | General |

| Proportion of patients post endometrial cancer surgery completing the recommended adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy course | Insurance (124) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of women receiving surgery for ovarian cancer who receive the recommended adjuvant chemotherapy post operatively | Income (160) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients discharged post lower limb trauma admission who receive follow up inpatient care | Insurance (234) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patients with cervical cancer who undergo surgery and do not receive the recommended postoperative radiotherapy | Insurance (125) | Gynecologic oncology |

| Proportion of patients who receive a stoma reversal | Racial/ethnic (69) ; insurance (69) ; income (69) |

General |

| Proportion of patients receiving post hospital trauma care | Insurance (235) | General |

| Proportion of people with a colon cancer colectomy who receive the recommended adjuvant chemotherapy | Geography (236) | Colon & rectal |

| Proportion of patients with primary extremity soft tissue sarcoma who receive adjuvant radiation | Racial/ethnic (211) | Orthopedic |

| Proportion of patient who have femoral shaft internal fixation materials removed | Racial/ethnic (70); Income (70) |

Orthopedic |

| Proportion of prelingual patients who receive a cochlear implant undergoing a sequential cochlear implantation on the other side | Insurance (237) | Otolaryngology |

| Proportion of patients who miss a follow up appointment post cochlear implantation | Insurance (237) | Otolaryngology |

| Proportion of patients who fail to arrive at an appointment at a tertiary hand surgery referral center | Insurance (143) | Orthopedic |

Disparity groups

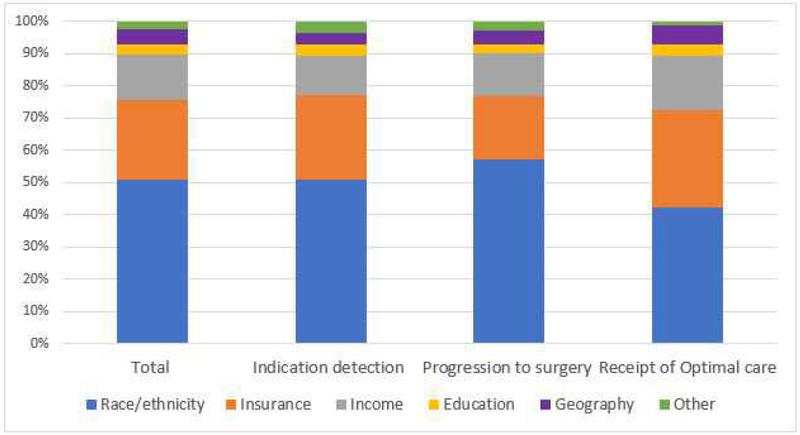

The measures of surgical access were categorized into six disparity domains; racial/ethnic, education, insurance, income, geography, and other (e.g. marital status, sex, immigration status). Figure 3 shows that the proportion of measures in each group remained similar throughout the phases of the conceptual surgical access model.

Fig 3.

Measures of surgical access disparities in each surgical access segment categorized by disparity domain (race/ethnicity, insurance. income. education, geography, and other).

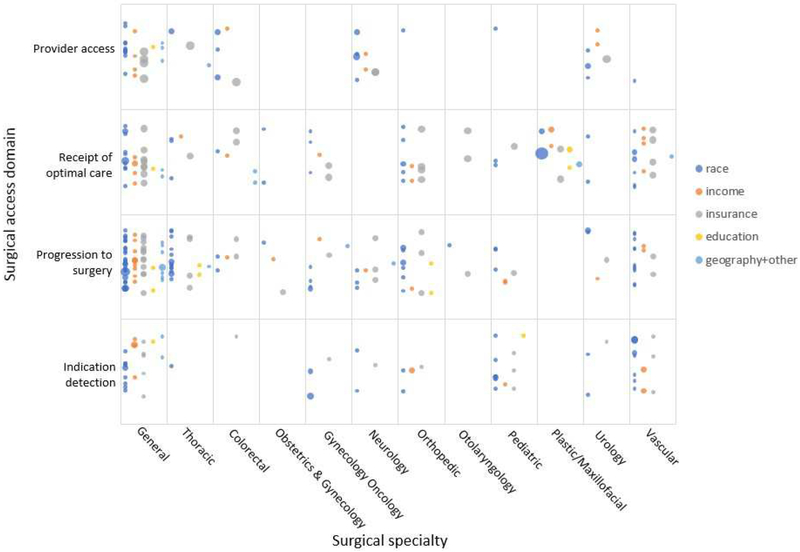

Evidence map

An evidence map illustrating the 223 measures of surgical access disparities in the US, stratified by surgical access domain, surgical specialty and disparity domain is shown in Figure 4. Two surgical specialties (ophthalmic and oral maxillofacial) did not have any measures of disparities identified and were thus not included in the evidence map.

Fig 4.

Evidence map of measures of surgical access disparities in the US. *Bubble size indicates number of studies supporting each measure. Plotting of the bubbles in each cell is systematic to increase readability of the figure. Horizontally, the bubbles are in five rows based on the disparity domain (color). A random placement generator was used to distribute bubbles vertically inside each cell.

Discussion

Measures of surgical access disparities in the US have been broadly applied; our novel conceptual model, illustrates the multiple interrelated strata of disparities. By further compartmentalizing surgical access disparities, more targeted interventions can be developed to accurately measure and address them.

For breast cancer surgical care, as an example, there are various measures in each surgical access domain. Racial/ethnic minority patients are more likely to access care at lower quality providers (71, 72), the indication for surgery is detected later (present at a later stage of diagnosis (18, 19)), progression to surgery takes longer (increased biopsy diagnosis to surgery time (43–45)), and indicated surgical treatment is less likely to occur (43, 73–75). If a surgical procedure is performed, it may not be the optimal procedure for the patient and the patient may not receive the adequate follow-up (less breast-conserving surgery vs. mastectomy (19, 66, 67), less likely to receive the full indicated postoperative radiotherapy course (43), less likely to have recommended sentinel lymph node biopsies (76), lower post-mastectomy breast reconstruction rates (48–56, 77, 78)). This can be simplified to say that racial/ethnic minority populations have less access to breast cancer surgical care, but by addressing each domain, a more thorough understanding is developed.

Each disparity measure in each facet of the surgical access model may have a multitude of causal factors. Etiologies contributing to disparities in surgical access include; healthcare literacy, ability to navigate the healthcare system, mistrust of healthcare providers and hospitals, healthcare affordability, misunderstanding of disease severity and treatment options, and a lack of access to adequate health care facilities and qualified personnel (8, 79–83).

Another factor to consider is implicit bias in the healthcare system towards minority groups (84, 85). Implicit bias is defined as a ubiquitous societal preference for a social group that is both unconscious and automatic informed by an individual’s experiences and perceptions of others (86). Physician implicit bias may negatively impact patient communication, clinical assessments, and decision-making for vulnerable patients (87–89).

The disparity domains examined are co-linear. Race/ethnicity and the various social determinants of health are intricately linked. Some studies adjust for the confounding effects of each determinant. While this allows a category such as race/ethnicity to be examined individually, it may not reflect the true extent of the ‘real-life’ disparity for these groups.

Most of the studies examining surgical access disparities utilized large existing retrospective databases. The disparity domains examined are thus limited to the availability of these variables in the databases themselves. The disparity domain for measures of surgical access disparities were predominately race/ethnicity followed by insurance status and income. Few studies examined other disparity domains such as HIV status (90), immigration status (14), linguistic isolation (91) and residing in a high health risk community (92).

Limitations of this review include that all measures were stratified into one surgical specialty and surgical access domain. Some cumulative disparity measures may include more than one surgical specialty. These were largely classified as general – this may skew the evidence map displaying access disparities towards general surgery. We included only studies quantitatively comparing surgical access measures which found a significant disparity. As such, if the evidence map does not show a measure in each area, it is not known whether this is because there is no research in this area or if there is literature that did not find a significant disparity.

The evidence map illustrates areas for future targeted quality improvement intervention and areas where more research is needed. Cells populated with many measures are areas where disparity improvement initiatives may be targeted. An example of a populated cell is the surgical indication detection domain in vascular surgery. Measures in this cell are largely delays in presentation of peripheral arterial disease or abdominal aortic aneurysms, presentation delays may result in emergent and/or more invasive surgical procedures. Quality improvement efforts to reduce disparities in this area may be warranted. The evidence map also illustrates cells with few or no measures, some of these cells are in surgical fields where there are known disparities in surgical outcomes. These are areas where further health outcomes research examining disparities are warranted.

Conclusion

Two hundred and twenty-three measures of surgical access disparities in the US are available. These measures were categorized using a four-faceted conceptual model for surgical access; Provider Access, Surgical Indication Detection, Progression to Surgery and Receipt of Optimal Care. This model establishes a novel paradigm for conceptualizing surgical access disparities. These measures were illustrated in an evidence map which displays many critical gaps in the literature. It is essential to incorporate measures of surgical access disparities into future surgical improvement initiatives.

Acknowledgments

Support: This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institute of Health under award number: 5RO1MD011695–02. Elzerie de Jager is a Doctor of Philosophy candidate at an Australian university, this research degree is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

References

- 1.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40:52–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:482–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torain MJ, Maragh-Bass AC, Dankwa-Mullen I, et al. Surgical Disparities: A Comprehensive Review and New Conceptual Framework. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:408–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenfeld AJ, Belmont PJ Jr., See AA, et al. Patient demographics, insurance status, race, and ethnicity as predictors of morbidity and mortality after spine trauma: a study using the National Trauma Data Bank. Spine J. 2013:1766–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen GC, Laveist TA, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Race is a predictor of in-hospital mortality after cholecystectomy, especially in those with portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reames BN, Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Ghaferi AA. Socioeconomic disparities in mortality after cancer surgery: failure to rescue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:475–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.In: Millman M, ed. Access to Health Care in America. Washington (DC); 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayanian JZ. Determinants of racial and ethnic disparities in surgical care. World J Surg. 2008;32:509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg JM, Power EJ. Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. JAMA. 2000;284:2100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e316–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr BG, Bowman AJ, Wolff CS, et al. Disparities in access to trauma care in the United States: A population-based analysis. Injury. 2017;48:332–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyrick JM, Kalosza BA, Coritsidis GN, Tse R, Agriantonis G. Trauma care in a multiethnic population: effects of being undocumented. The J Surg Res. 2017;214:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty AL, Bradley SM, Maynard C, McCabe JM. Referral to Cardiac Rehabilitation After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery, and Valve Surgery: Data From the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuistion K, Zens T, Jung HS, et al. Insurance status and race affect treatment and outcome of traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 2016;205:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budnick HC, Tyroch AH, Milan SA. Ethnic disparities in traumatic brain injury care referral in a Hispanic-majority population. J Surg Res. 2017;215:231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiraldi M, Patil CG, Mukherjee D, et al. Effect of insurance and racial disparities on outcomes in traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurological surgery Part A, Cen Eur Neurosurg. 2015;76:224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Churilla TM, Egleston B, Bleicher R, et al. Disparities in the Local Management of Breast Cancer in the US according to Health Insurance Status. Breast J. 2017;23:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen BC, Alawadi ZM, Roife D, et al. Do Socioeconomic Factors and Race Determine the Likelihood of Breast-Conserving Surgery? Clin Breast cancer. 2016;16:93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akinyemiju T, Moore JX, Ojesina AI, et al. Racial disparities in individual breast cancer outcomes by hormone-receptor subtype, area-level socio-economic status and healthcare resources. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;157:575–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukavsky R, Sariego J. Insurance status effects on stage of diagnosis and surgical options used in the treatment of breast cancer. South Med J. 2015;108:258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien B, Koru-Sengul T, Miao F, et al. Disparities in Overall Survival for Male Breast Cancer Patients in the State of Florida (1996–2007). Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15:177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang RL, Newman AS, Lin IC, et al. Trends in immediate breast reconstruction across insurance groups after enactment of breast cancer legislation. Cancer. 2013;119:2462–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulte D, Jansen L, Brenner H. Population-Level Differences in Rectal Cancer Survival in Uninsured Patients Are Partially Explained by Differences in Treatment. Oncologist. 2017;22:351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu JC, Neugut AI, Wang S, et al. Racial and insurance disparities in the receipt of transplant among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:1801–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou H, Zhang Y, Wei X, et al. Racial disparities in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors survival: a SEER study. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivero M, Nader ND, Blochle R, et al. Poorer limb salvage in African American men with chronic limb ischemia is due to advanced clinical stage and higher anatomic complexity at presentation. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:1318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loehrer AP, Hawkins AT, Auchincloss HG, et al. Impact of Expanded Insurance Coverage on Racial Disparities in Vascular Disease: Insights From Massachusetts. Ann Surg. 2016;263:705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien-Irr MS, Harris LM, Dosluoglu HH, Dryjski ML. Procedural trends in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease by insurer status in New York State. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durham CA, Mohr MC, Parker FM, et al. The impact of socioeconomic factors on outcome and hospital costs associated with femoropopliteal revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim LK, Swaminathan RV, Minutello RM, et al. Trends in hospital treatments for peripheral arterial disease in the United States and association between payer status and quality of care/outcomes, 2007–2011. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:864–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ladd MR, Pajewski NM, Becher RD, et al. Delays in treatment of pediatric appendicitis: a more accurate variable for measuring pediatric healthcare inequalities? Am Surgeon. 2013;79:875–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavernia CJ, Villa JM. Does Race Affect Outcomes in Total Joint Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alas AN, Dunivan GC, Wieslander CK, et al. Health Care Disparities Among English-Speaking and Spanish-Speaking Women With Pelvic Organ Prolapse at Public and Private Hospitals: What Are the Barriers? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22:460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riall TS, Townsend CM Jr., Kuo YF, et al. Dissecting racial disparities in the treatment of patients with locoregional pancreatic cancer: a 2-step process. Cancer. 2010;116:930–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiley S, Meinzen-Derr J. Access to cochlear implant candidacy evaluations: who is not making it to the team evaluations? Int J Audiol. 2009;48:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Jarl J, Gerdtham UG. Are There Inequities in Treatment of End-Stage Renal Disease in Sweden? A Longitudinal Register-Based Study on Socioeconomic Status-Related Access to Kidney Transplantation. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2017;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Racial disparities in total knee replacement among Medicare enrollees--United States, 2000–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, et al. Age and racial/ethnic disparities in arthritis-related hip and knee surgeries. Med Care. 2008;46:200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson CT, Fisher E, Welch HG. Racial disparities in abdominal aortic aneurysm repair among male Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Surg. 2008;143:506–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halm EA, Tuhrim S, Wang JJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes and appropriateness of carotid endarterectomy: impact of patient and provider factors. Stroke. 2009;40:2493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curry WT Jr., Carter BS, Barker FG 2nd. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in patient outcomes after craniotomy for tumor in adult patients in the United States, 1988–2004. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013;310:389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosunjac M, Park J, Strauss A, et al. Time to treatment for patients receiving BCS in a public and a private university hospital in Atlanta. Breast. 2012;18:163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bustami RT, Shulkin DB, O’Donnell N, Whitman ED. Variations in time to receiving first surgical treatment for breast cancer as a function of racial/ethnic background: a cohort study. JRSM Open. 2014;5:2042533313515863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang L, Haberland C, Thurm C, et al. Health outcomes in US children with abdominal pain at major emergency departments associated with race and socioeconomic status. PLoS One. 2015;10: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wise ES, Ladner TR, Song J, et al. Race as a predictor of delay from diagnosis to endarterectomy in clinically significant carotid stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauder AR, Gross CP, Killelea BK, et al. The Relationship Between Geographic Access to Plastic Surgeons and Breast Reconstruction Rates Among Women Undergoing Mastectomy for Cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78:324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma K, Grant D, Parikh R, Myckatyn T. Race and Breast Cancer Reconstruction: Is There a Health Care Disparity? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:354–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahmoudi E, Giladi AM, Wu L, Chung KC. Effect of federal and state policy changes on racial/ethnic variation in immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:1285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenberg CC, Schneider EC, Lipsitz SR, et al. Do variations in provider discussions explain socioeconomic disparities in postmastectomy breast reconstruction? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:605–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kruper L, Holt A, Xu XX, et al. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy: patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction in Southern California. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kruper L, Xu X, Henderson K, Bernstein L. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction for DCIS compared with invasive cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3210–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sisco M, Du H, Warner JP, Howard MA, Winchester DP, Yao K. Have we expanded the equitable delivery of postmastectomy breast reconstruction in the new millennium? Evidence from the national cancer data base. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Shickle LM, Lee W. Surgery wait times and specialty services for insured and uninsured breast cancer patients: does hospital safety net status matter? Health Serv Res. 2012;47:677–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shippee TP, Kozhimannil KB, Rowan K, Virnig BA. Health insurance coverage and racial disparities in breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tseng WH, Stevenson TR, Canter RJ, et al. Sacramento area breast cancer epidemiology study: use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction along the rural-to-urban continuum. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1815–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dubecz A, Solymosi N, Schweigert M, et al. Time trends and disparities in lymphadenectomy for gastrointestinal cancer in the United States: a population-based analysis of 326,243 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taioli E, Flores R. Appropriateness of Surgical Approach in Black Patients with Lung Cancer-15 Years Later, Little Has Changed. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, Hutter MM. Influence of Health Insurance Expansion on Disparities in the Treatment of Acute Cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weber DJ, Shoham DA, Luke A, et al. Racial odds for amputation ratio in traumatic lower extremity fractures. J Trauma. 2011;71:1732–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ricciardi R, Selker HP, Baxter NN, et al. Disparate use of minimally invasive surgery in benign surgical conditions. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mehta A, Xu T, Hutfless S, et al. Patient, surgeon, and hospital disparities associated with benign hysterectomy approach and perioperative complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abenhaim HA, Azziz R, Hu J, et al. Socioeconomic and racial predictors of undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy for selected benign diseases: analysis of 341487 hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, Hutter MM. Massachusetts health care reform and reduced racial disparities in minimally invasive surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olaya W, Wong JH, Morgan JW, et al. Disparities in the surgical management of women with stage I breast cancer. Am Surg. 2009;75:869–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akinyemiju TF, Vin-Raviv N, Chavez-Yenter D, et al. Race/ethnicity and socio-economic differences in breast cancer surgery outcomes. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39:745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alderman AK, Bynum J, Sutherland J, et al. Surgical treatment of breast cancer among the elderly in the United States. Cancer. 2011;117:698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zafar SN, Changoor NR, Williams K, et al. Race and socioeconomic disparities in national stoma reversal rates. Am J Surg. 2016;211:710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dodwell E, Wright J, Widmann R, et al. Socioeconomic Factors Are Associated With Trends in Treatment of Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures, and Subsequent Implant Removal in New York State. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36:459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell JE, Janitz AE, Vesely SK, et al. Patterns of Care for Localized Breast Cancer in Oklahoma, 2003–2006. Women Health. 2015;55:975–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of high-volume hospitals and surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Popescu I, Schrag D, Ang A, Wong M. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Differences in Colorectal and Breast Cancer Treatment Quality: The Role of Physician-level Variations in Care. Med Care. 2016;54:780–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Esnaola NF, Knott K, Finney C, et al. Urban/rural residence moderates effect of race on receipt of surgery in patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer: a report from the South Carolina central cancer registry. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1828–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keating NL, Kouri E, He Y, et al. Racial differences in definitive breast cancer therapy in older women: are they explained by the hospitals where patients undergo surgery? Med Care. 2009;47:765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Black DM, Jiang J, Kuerer HM, et al. Racial disparities in adoption of axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphedema risk in women with breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:788–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosson GD, Singh NK, Ahuja N, et al. Multilevel analysis of the impact of community vs patient factors on access to immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy in Maryland. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1076–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Offodile AC 2nd, Tsai TC, Wenger JB, Guo L. Racial disparities in the type of postmastectomy reconstruction chosen. J Surg Res. 2015;195:368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Amaranto DJ, Abbas F, Krantz S, et al. An evaluation of gender and racial disparity in the decision to treat surgically arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gornick ME, Eggers PW, Reilly TW, et al. Effects of race and income on mortality and use of services among Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:791–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Katz JN. Patient preferences and health disparities. JAMA. 2001;286:1506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Voorhees K, Fernald DH, Emsermann C, et al. Underinsurance in primary care: a report from the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices and Partners (SNOCAP). J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21:309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haider AH, Sexton J, Sriram N, et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. JAMA. 2011;306:942–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychol Sci. 2000;11:315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008;46:678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Hinze SW, et al. The effect of race/ethnicity and desirable social characteristics on physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioid analgesics. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1239–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Loehrer AP, Chang DC, Hutter MM, et al. Health Insurance Expansion and Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer: Does Increased Access Lead to Improved Care? J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:1015–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patzer RE, Plantinga LC, Paul S, et al. Variation in Dialysis Facility Referral for Kidney Transplantation Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease in Georgia. JAMA. 2015;314:582–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph GW, Srivastav S, Kandil E. Outcomes in endocrine cancer surgery are affected by racial, economic, and healthcare system demographics. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoehn RS, Hanseman DJ, Dhar VK, et al. Opportunities to Improve Care of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Vulnerable Patient Populations. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chang DC, Zhang Y, Mukherjee D, et al. Variations in referral patterns to high-volume centers for pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:720–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang W, Lyman S, Boutin-Foster C, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Utilization Rate, Hospital Volume, and Perioperative Outcomes After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.SooHoo NF, Farng E, Zingmond DS. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for total hip replacement. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph GW, Srivastav S, et al. Outcomes in thyroid surgery are affected by racial, economic, and healthcare system demographics. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hauch A, Al-Qurayshi Z, Friedlander P, Kandil E. Association of socioeconomic status, race, and ethnicity with outcomes of patients undergoing thyroid surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:1173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mehta RH, Shahian DM, Sheng S, et al. Association of Hospital and Physician Characteristics and Care Processes With Racial Disparities in Procedural Outcomes Among Contemporary Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery. Circulation. 2016;133:124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bao Y, Kamble S. Geographical distribution of surgical capabilities and disparities in the use of high-volume providers: the case of coronary artery bypass graft. Med Care. 2009;47:794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hauch A, Al-Qurayshi Z, Kandil E. The effect of race and socioeconomic status on outcomes following adrenal operations. J Surg Onc. 2015;112:822–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim J, ElRayes W, Wilson F, et al. Disparities in the receipt of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: between-hospital and within-hospital analysis using 2009–2011 California inpatient data. BMJ open. 2015;5:007409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pollack CE, Bekelman JE, Epstein AJ, et al. Racial disparities in changing to a high-volume urologist among men with localized prostate cancer. Med Care. 2011;49:999–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Huang LC, Tran TB, Ma Y, et al. Factors that influence minority use of high-volume hospitals for colorectal cancer care. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:526–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hicks CW, Hashmi ZG, Hui X, et al. Explaining the Paradoxical Age-based Racial Disparities in Survival After Trauma: The Role of the Treating Facility. Ann Surg. 2015;262:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Henry AJ, Hevelone ND, Belkin M, Nguyen LL. Socioeconomic and hospital-related predictors of amputation for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:330–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mukherjee D, Kosztowski T, Zaidi HA, et al. Disparities in access to pediatric neurooncological surgery in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:688–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mukherjee D, Zaidi HA, Kosztowski TA, et al. Variations in referral patterns for hypophysectomies among pediatric patients with sellar and parasellar tumors. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stitzenberg KB, Meropol NJ. Trends in centralization of cancer surgery. Ann Surg Onc. 2010;17:2824–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Ibeanu OA. Racial disparities in ovarian cancer surgical care: a population-based analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu FW, Randall LM, Tewari KS, Bristow RE. Racial disparities and patterns of ovarian cancer surgical care in California. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Armstrong K, Randall TC, Polsky D, et al. Racial differences in surgeons and hospitals for endometrial cancer treatment. Med Care. 2011;49:207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fleury AC, Ibeanu OA, Bristow RE. Racial disparities in surgical care for uterine cancer. Gynecol Onc. 2011;121:571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schroeck FR, Hollingsworth JM, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Differential adoption of laser prostatectomy for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2013;81:1177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nuno M, Drazin DG, Acosta FL Jr.. Differences in treatments and outcomes for idiopathic scoliosis patients treated in the United States from 1998 to 2007: impact of socioeconomic variables and ethnicity. Spine J. 2013;13:116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sun M, Karakiewicz PI, Sammon JD, et al. Disparities in selective referral for cancer surgeries: implications for the current healthcare delivery system. BMJ open. 2014;4:003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Attenello FJ, Adamczyk P, Wen G, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to mechanical revascularization procedures for acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:327–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jacobs AJ, Lindholm EB, Levy CF, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment and survival of pediatric sarcoma. The J Surg Res. 2017;219:43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Garner EF, Maizlin II, Dellinger MB, et al. Effects of socioeconomic status on children with well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2017;162:662–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]