Abstract

Introduction:

Canadian provincial and territorial governments have enacted legislation in response to health risks of artificial ultraviolet radiation from indoor tanning. This legislation, which differs from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, regulates the operation of indoor tanning facilities. The content and comprehensiveness of such legislation—and its differences across jurisdictions—have not been analyzed. To address this research gap, we conducted a systematic, comprehensive scan and content analysis on provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation, including regulations and supplementary information.

Methods:

Legislative information was collected from the Canadian Legal Information Institute database and an environmental scan was conducted to locate supplementary information. Through a process informed by the content of the legislation, previous research and health authority recommendations, we developed a 59-variable codebook. Descriptive statistics were calculated.

Results:

All provinces and one of three territories have legislation regulating indoor tanning. Areas of strength across jurisdictions are youth access restrictions (n = 11), posting of warning signs (n = 11), penalties (n = 11) and restrictions on advertising and marketing targeted to youth (n = 7). Few jurisdictions, however, cover areas such as protective eyewear (n = 4), unsupervised tanning (n = 4), provisions for inspection frequency (n = 4), misleading health claims in advertisements directed toward the general public (n = 2) and screening of high-risk clients (n = 0).

Conclusion:

All provinces and one territory have made progress in regulating the indoor tanning industry, particularly by prohibiting youth and using warning labels to communicate risk. Legislative gaps should be addressed in order to better protect Canadians from this avoidable skin cancer risk.

Keywords: health policy, ultraviolet radiation, skin cancer, melanoma, indoor tanning, suntan, ultraviolet rays, skin neoplasms

Highlights

All Canadian provinces and one of three territories have enacted indoor tanning legislation.

There was a strong emphasis in the legislation on restricting youth access to indoor tanning and advertising and marketing of indoor tanning services to youth.

Other well-covered areas were presence of warning signs and indication of penalties for infractions.

Areas that likely require stronger legislative action include risk information provided to clients, client protection with respect to areas such as eyewear and exposure dose and restrictions on advertising and marketing to the general public.

Very few jurisdictions identified inspection frequency, which may have implications for compliance by indoor tanning businesses.

Introduction

Skin cancer, commonly classified as either melanoma or non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), is the most common type of cancer in Canada.1 The incidence of melanoma, the most fatal form of skin cancer, is increasing steadily—2.1% in males and 2.0% in females1,2 every year between 1992 and 2013. In 2017, it was projected that 7200 Canadians would be newly diagnosed with melanoma and 1250 would die from this cancer.2 Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, including that from tanning equipment, has been demonstrated to increase the risk of skin cancer, including potentially fatal cutaneous and ocular melanomas.3,4 UV radiation has been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a human carcinogen.3

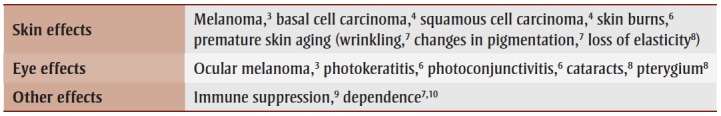

The risk of skin cancer due to indoor tanning is especially pronounced if first use occurs at an early age: there is a 59% higher risk of cutaneous melanoma among people who begin using indoor tanning devices before the age of 35 than among those who have never used tanning beds.5 Studies have also reported increased odds of ocular melanoma if exposure to tanning equipment begins before age 20.3 The use of these devices before the age of 25 can also increase the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer, including basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. 4 Table 1 summarizes the risks associated with UV tanning found in the literature.3,4,6-10

Table 1. Negative outcomes associated with UV tanning.

|

Despite these risks, an estimated 1.35 million Canadians participated in this activity in 2014.11 In addition, though the risk of skin cancer is higher if first use of indoor tanning devices occurs early in life4,5 and melanoma is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in youth aged 15 to 29,12 use of indoor tanning devices is highest among young people, particularly young women.11 These trends may be due in part to the propagation of tanned skin as a beauty ideal, conflicting information on the dangers of indoor tanning in the media13 and misleading claims from the indoor tanning industry.14

Legislation regulating indoor tanning facilities influences the use of these devices, especially by young people. For example, a study in the United States of America (USA) determined that adolescent females in states with indoor tanning legislation were less likely to tan indoors.15 In addition, legislation has been noted as possibly contributing to declines in smoking rates and changes in attitudes toward smoking, as well as reduced incidence of traffic deaths related to impaired driving and absence of seatbelts.16-18 As it has for these issues, health policy may impact indoor tanning behaviours.

In Canada, legislation addressing indoor tanning exists at the federal level as the Radiation Emitting Devices (RED) Act and Regulations.19,20 This legislation regulates certain features of indoor tanning equipment sold in Canada, such as timers and UV bulbs used in the devices, and manufacturers’ labels.20 Health Canada has also developed the voluntary Guidelines for Tanning Salon Owners, Operators, and Users, which contain recommendations for the use of indoor tanning devices.6However, the responsibility of regulating tanning salon operation falls on the provincial and territorial governments, who, along with some municipalities, have enacted legislation in this area. These laws are often described in Acts enacted by provincial legislative assemblies.21 Acts may also designate a person or group to develop additional rules and further guide the Act through pieces of legislation known as regulations.21

Though it is known that provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation does exist, a comprehensive analysis of this policy across provinces and territories has not yet been conducted. Analyses of such legislation in the USA by Woodruff et al. and Gosis et al. have provided useful comparisons in the indoor tanning legislation between states and across several key aspects of tanning facility operation.22,23 They have also highlighted areas of strength and areas for potential improvement in the legislation.22,23 Similarly, analyses of other forms of health legislation covering areas such as tobacco, alcohol and behaviours surrounding obesity have been conducted.24-28 These have provided valuable information on the state and coverage of these health policies.24-28 Analyzing the content of Canadian indoor tanning legislation will therefore allow for the collection of information that may assist in future policy developments in this field. To obtain this information and fill the current gap in the research on Canadian indoor tanning legislation, we collected all provincial and territorial legislative and supplementary information and conducted a content analysis of these laws.

This paper outlines the collection of this legislative information; development of a codebook to conduct the content analysis; and the results and applications of this research.

Methods

Content analyses are a useful approach for studying and comparing legislative content.29 The methodology of this study involved systematically collecting all Canadian provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation; locating any material supplementary to the legislation; developing a codebook to analyze the legislation; and conducting a comprehensive content analysis on all information collected.

Collection of legislation and supplementary information

We located current Acts and regulations in the “Legislation” category of the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII) database using the “Document Text” search function. Search parameters were restricted to one province or territory at a time. Search terms included the disease (“skin cancer”), the activity (“tanning”) and the exposure (“ultraviolet light,” “UV light,” ultraviolet radiation,” “UV radiation”). For each piece of legislation, CanLII provided links to regulations and enabling statutes where applicable. Some pieces of indoor tanning legislation also described additional Acts that address areas such as enforcement. These Acts were collected in CanLII with the name of the legislation as the search term. Table 2 contains all legislative and supplementary information collected, as well as the enforcement status of each law.

Table 2. Canadian indoor tanning legislative and supplementary information collected and status of legislation.

Indoor tanning legislation was not located for Nunavut and Yukon on CanLII. The absence of indoor tanning legislation in these territories was confirmed using each territory’s legislative website.

In many cases, provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation was accompanied by supplementary materials to provide information beyond the legislative contents and to help tanning salon operators and clients interpret the legislation. Common examples of this supplementary information included guidelines for tanning salon operators, copies of warning signs for posting on the premises and webpages provided by provincial or territorial health authorities with more information on areas such as enforcement and inspection.

An environmental scan was used to collect any relevant supplementary information or materials related to each province’s indoor tanning legislation. We obtained this information using the search functions on provincial and territorial health ministry websites. Search terms used on each of these websites included “tanning” and “indoor tanning.” To obtain more information on inspection, we also included the search term “tanning inspection” on all health ministry websites. In Quebec, we also included the search term “bronzage” in order to capture material in French.

Codebook development and application

Once all legislative information was collected, we developed a comparison chart of indoor tanning legislation to highlight common features of Canadian indoor tanning legislation, which we incorporated into the codebook. The codebook was also informed by research and recommendations from major public health authorities. For example, variables sourced from guidelines developed by WHO for tanning salon operators included the refusal of services to clients prone to sunburn and prohibition of misleading health claims in advertisements.8 Some variables sourced from Health Canada’s 2014 Guidelines for Tanning Salon Owners, Operators, and Users included compliance with tanning device manufacturers’ recommended maximum exposure duration and use of protective eyewear.6 These recommendations from WHO and Health Canada served as examples of contents that the ideal indoor tanning legislation may have.

Some variables used in the studies on US indoor tanning legislation, such as enforcement authority,23 proof of operator training22 and provisions for checking client age identification,23 were also incorporated in this codebook. One of these studies did not provide the full scoring tool used in the research; this was obtained by contacting the principal investigator.

We developed the codebook and applied it to the legislation through a consensusbased process. A draft incorporating the information described above was created, and then applied to a sample of provinces or territories while any coding issues were discussed among the research team. We then revised the codebook, and repeated this process until a final version was developed. We applied this final codebook to all legislative contents while regularly discussing the process and any remaining issues. Throughout the codebook development and final coding process, we obtained and incorporated feedback from policy experts and public health professionals in cases where the legislative language was ambiguous.

The final codebook consists of 12 categories, which are subdivided into 59 variables, each aligned to one legislative component. For most variables, coding was dichotomous and on a “presence” or “absence” basis for legislative components. However, some required more coding options to convey more detail about the legislative components. For example, it was necessary to create three coding options in the variable that analyzed indoor tanning prohibitions for youth: these options were “no,” “minimum age to access tanning services is 1–17” and “minimum age is 18 or 19.” When it was important to determine the specificity of the legislative language for a particular variable, coding options were created to reflect this. For example, in the inspection authority variable under the enforcement category, there were three main coding options: “no,” “nonspecific person/group given as inspector” and “specific person/ group given as inspector.” This methodological approach was informed by the scoring tool developed by Gosis et al.23 Other variables required information that was specific to each province or territory, such as the number of warning signs required and details of penalties for violation of the legislation. In these cases, there were no coding options, but the information was entered directly into the data spreadsheet.

Once all materials were coded, we calculated descriptive statistics (frequencies) using SPSS version 25.0 for Mac (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). These statistics included the proportions of provinces and territories that were given each coding option for each variable.

Results

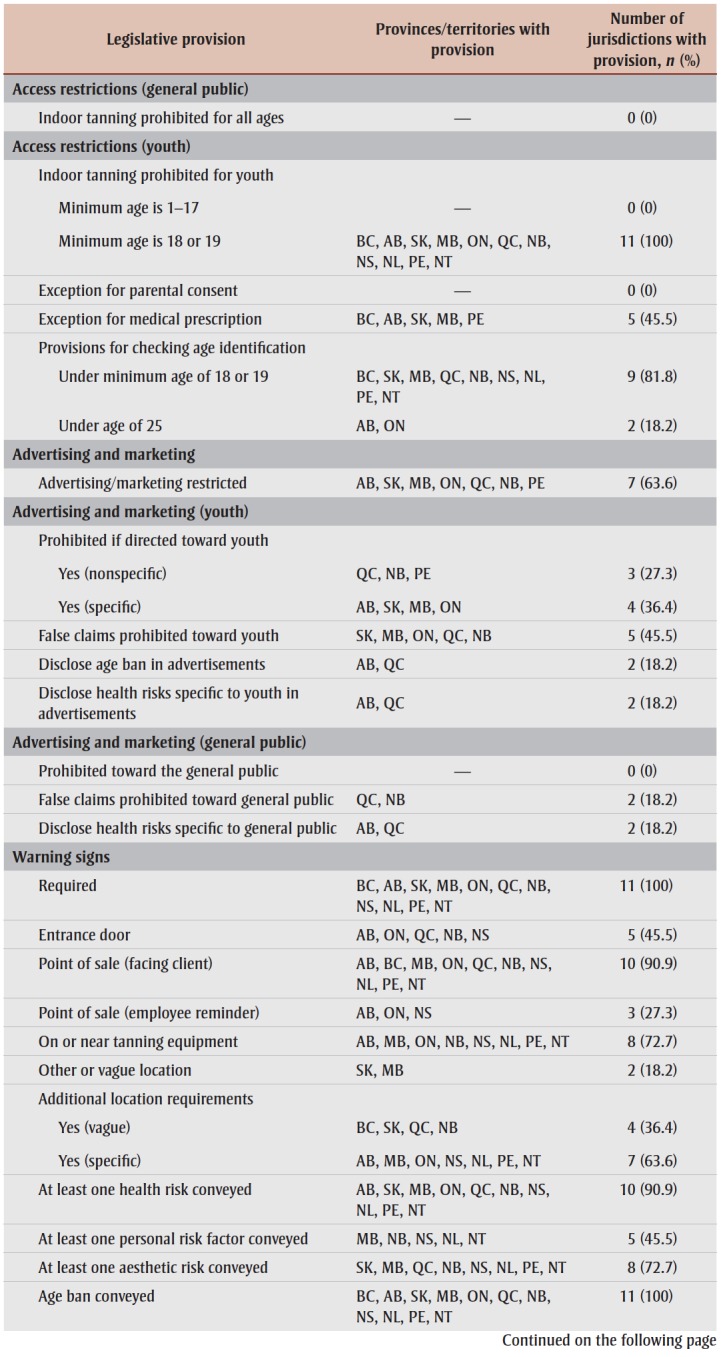

All 10 provinces and one of the three territories in Canada have introduced legislation to regulate indoor tanning; this equates to a national legislative coverage of 85%. Table 3 summarizes the results across all variables for the 11 provinces/ territories that have indoor tanning legislation.

Table 3. Comprehensiveness of indoor tanning legislation in eleven Canadian provinces/territories.

|

Access restrictions

All provinces/territories prohibit youth under the age of 18 or 19 (minors) from accessing indoor tanning services. However, no region has placed such prohibitions on those beyond this age group (i.e. adults are not prohibited from tanning in any jurisdiction). No jurisdiction allows exemptions to these laws for minors who have parental consent. However, five provinces/ territories allow minors who have a medical prescription to access indoor tanning services.

All provinces and territories require salon operators to check the ages of potential clients through photo identification to ensure that they meet the minimum age requirement. Nine have this requirement for persons who appear to be under the minimum age of 18 or 19, and two have this requirement for any potential client appearing to be under the age of 25.

Advertising and marketing

Of the 11 provinces and territories with indoor tanning legislation, seven have some restriction on advertising and marketing of indoor tanning services. All of these prohibit indoor tanning advertisements directed to youth, while none prohibit these advertisements from targeting members of other age groups (i.e., adults). Four provide specific language to explain provisions against youth-oriented advertisements (e.g., prohibitions on advertising in certain locations or media accessed frequently by youth). Five prohibit advertisements with misleading health claims directed to youth, while two prohibit these claims from targeting other age groups. Two jurisdictions with advertising restrictions require advertisements to disclose the minimum age requirements and health risks of indoor tanning with respect to people of all ages.

Warning signs

All provinces/territories with indoor tanning legislation require at least one warning sign to be posted in tanning facilities. The number of unique warning signs to be posted in indoor tanning facilities ranges from one (BC, SK, MB, PE) to four (AB, ON). Warning signs in all jurisdictions inform clients of the minimum age to access indoor tanning services. All but one province/territory require warning signs to indicate at least one health risk of indoor tanning (e.g., “skin cancer,” “serious injury” or “burns”). Eight include warning signs that indicate at least one aesthetic risk of indoor tanning (e.g., “premature aging” or “skin wrinkling”). In addition, about half mandate warning signs to communicate at least one personal characteristic (e.g., certain medical conditions, medications and skin types) that would increase a person’s likelihood of experiencing the adverse effects of indoor tanning.

The number of unique locations for warning signs in a tanning facility ranges from one (BC, SK) to four (AB, ON). The legislation for seven provinces/territories provides specific descriptions of required warning sign locations, such as maximum distance from tanning equipment or cash registers at point of sale. Four provide vague descriptions by stating that signage must be “prominent” or “easily viewed.” In terms of exact locations, five jurisdictions require warning signs to be posted on or near an entrance door to the premises, 10 require a sign to be visible to the client at point of sale, three require a sign to be visible to employees at the point of sale to remind them of the minimum age requirement and eight require a warning sign to be posted on or near tanning equipment. Two describe other or vague locations where warning signs must be posted: in Saskatchewan, the sign must be placed in a prominent or easily viewed location; in Manitoba, there is an option to place one of the required signs in any location where it can be seen by a person entering the facility.

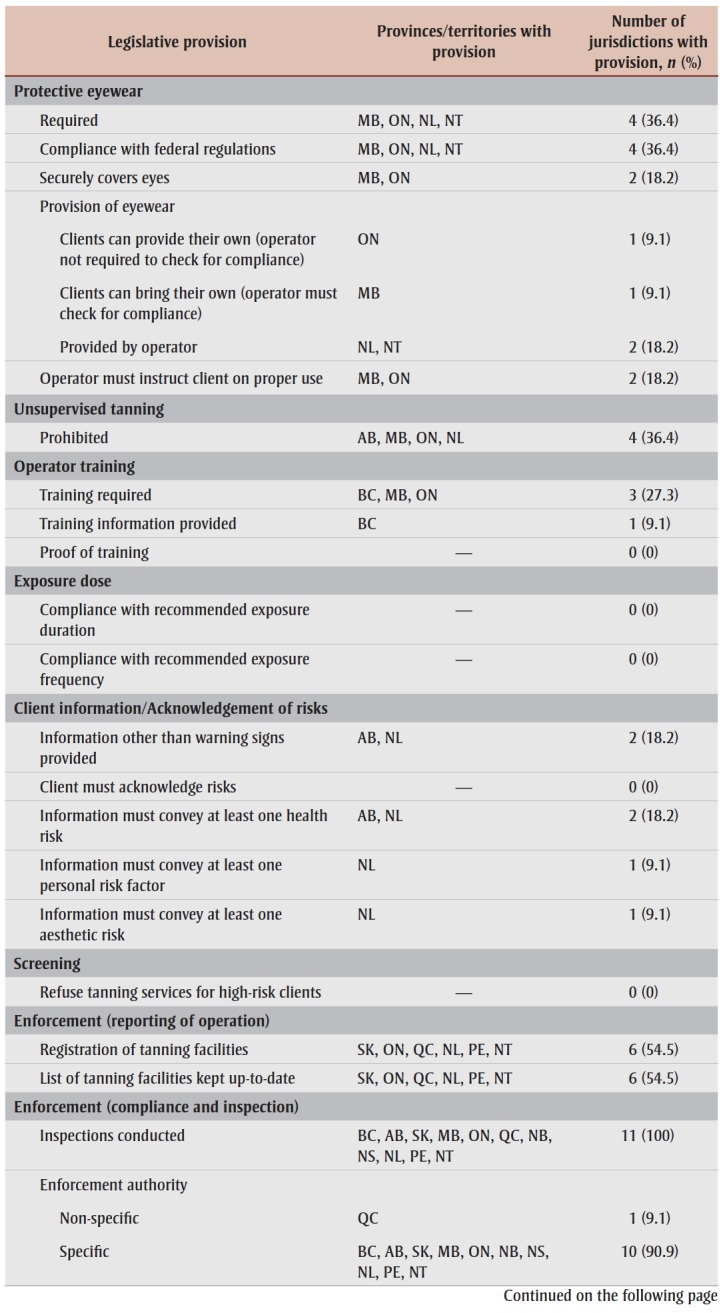

Protective eyewear

In total, four provinces/territories contain provisions for client use of protective eyewear while using indoor tanning equipment. All four also require that this eyewear comply with the specifications laid out in the RED Regulations and two of these provinces/territories state that the eyewear must securely cover the eyes of the user. Requirements for the provision of protective eyewear to clients varied across jurisdictions. One province allows clients to provide their own eyewear for use but does not specify that operators must examine the eyewear to determine compliance with the legislation. Another province states that clients may provide their own eyewear, but the operator must inspect it for compliance, while two other provinces/territories mandate that the tanning facilities provide the eyewear for purchase or use. In addition, two require operators to instruct clients on the proper use of protective eyewear before allowing access to indoor tanning equipment.

Unsupervised tanning

Four provinces/territories prohibit indoor tanning facilities from selling access to equipment that does not require monitoring by an attendant (i.e., coin-operated devices or any other equipment that clients can operate on their own).

Operator training

Salon operator training is mentioned in the legislation of three provinces/territories. One of these jurisdictions provides further information on how this training is to be conducted. None of the collected pieces of legislation state that operators must have proof of training.

Exposure dose

No jurisdiction requires tanning facilities to comply with the maximum exposure times or the minimum interval times between consecutive exposures, as recommended by the manufacturer.

Client information and acknowledgement of risks

Two provinces/territories require risk information be provided to clients in a format above and beyond warning signs. The client information provided by salon operators in both jurisdictions must contain at least one health risk of indoor tanning. However, only one jurisdiction (NL) requires that client information disclose at least one aesthetic risk and at least one personal factor that could increase a client’s risk of adverse effects. No province or territory requires clients to acknowledge verbally or with a signature that they understand the risk information provided.

Screening

No Canadian jurisdiction has made it mandatory for operators to recommend or require that certain high-risk potential clients (e.g. those with type 1 skin [highly sensitive, always burns, never tans]) avoid using indoor tanning devices.

Enforcement

Reporting of operation

Six provinces/territories require indoor tanning facilities to be registered with a health authority. All of these either describe methods of keeping registries of active tanning facilities accurate and upto- date or mention authorities responsible for this task.

Compliance and inspection

All provinces/territories with indoor tanning legislation require inspections of indoor tanning facilities to help ensure compliance. Two jurisdictions (SK, ON) mandate that inspections of indoor tanning facilities occur primarily in response to complaints. The legislation in five jurisdictions also indicates the possibility for proactive inspections (i.e., those that are not in response to complaints). Four provinces/ territories clearly indicate a requirement for these proactive inspections by providing a frequency at which indoor tanning facilities must be inspected: one provides a specific interval (“yearly” in NT) and three give vague frequencies (“regularly” in NL, “from time to time” in NS, “routinely” in PE).

In 10 jurisdictions, the legislation identifies at least one specific person or group responsible for conducting inspections, most commonly environmental health officers/ consultants (n = 5) or public health inspectors/officers (n = 5). It is explicitly stated in the legislation of three provinces/ territories that these inspectors may enter indoor tanning facilities without providing prior notice to owners or operators.

Penalties

Specific penalties are outlined in the legislation for all provinces/territories. Penalties are either described in the indoor tanning legislation or included in general penalties for violations of all provisions within public health acts. All penalties increase in severity for repeated or continued offences, or repeat for each day an offence continues. All provinces/territories describe fines as penalties for offences. However, some public health acts also mention imprisonment as the penalty for an offence. In Nova Scotia, suspensions from providing indoor tanning services are also possible penalties. In Quebec, there is a $100 fine for minors who were found accessing indoor tanning services.

Discussion

Most provinces and territories have introduced legislation to protect Canadians from the health risks associated with artificial tanning, which represents important progress considering no provincial or territorial indoor tanning legislation existed seven years ago. This legislation is very much focused on youth access restrictions. Coverage of warning signs, penalties and advertising directed to youth were also strong. However, there were some gaps across jurisdictions in terms of other forms of risk communication, screening of potential clients, unsupervised tanning restrictions, compliance with manufacturer exposure recommendations and protective eyewear requirements. In addition, while all jurisdictions mandate inspections, the way these provisions are laid out in the legislation may not ensure sufficient enforcement.

Indoor tanning legislation was not present in Nunavut and Yukon, each with a population of 36 000.30,31 An Internet search indicates there are few tanning facilities operating in each territory. We are not aware if these territories have the resources for regulating these issues. However, it may be possible for them to adopt other provincial laws. In addition, an existing bylaw in the City of Whitehorse, Yukon, likely covers the majority of tanning salons in Yukon.32

The fact that all jurisdictions with indoor tanning legislation prohibit the sale of indoor tanning services to minors is likely due to findings that the risks of indoor tanning are especially pronounced in this group, as well as to the legal precedent of restricting alcohol and tobacco to youth. This is an important step, as it was found that female high school students in the USA, for example, were less likely to use these services if they live in states with age restriction laws;15 in Canada, the highest prevalence of indoor tanning is among young women.11 However, although the risk of developing cutaneous melanoma from indoor tanning devices is particularly high in those who first use them before age 35,5 incidence is higher in older Canadians.1 Despite this, no laws in Canada prevent those over 18 or 19 from using indoor tanning beds.

Other high-risk Canadians may also be permitted to undergo harmful exposure to UV radiation under provincial and territorial legislation, since most jurisdictions do not require that clients be screened prior to using indoor tanning devices. For example, 28% of Canadian indoor tanning device users are reported to have skin that is susceptible to sunburn11 while Health Canada recommends that people who always burn and never tan should be advised against indoor tanning.6

Most, but not all, provinces and territories with indoor tanning legislation require that health and aesthetic risks, as well as personal risk factors, of indoor tanning be displayed in warning labels in tanning facilities. This is promising, given the success of tobacco warning labels. However, and of concern, approximately half of indoor tanning users do not consult the posted warning signs each time they tan.11 Thus, there is a need for risk information through other means, such as documents or verbal communication provided by salon operators. However, only two provinces currently require operators to do this, representing a potential area for improvement.

While warning signs are important, the people seeing them are already somewhat committed to the behaviour. Therefore, communicating health risks and preventing misinformation through advertisements is also important. However, most jurisdictions do not require tanning facilities to disclose this risk information when advertising their services. In addition, in most—but not all—provinces and territories, regulation of misleading advertisements directed toward youth was common, while misleading advertisements directed toward the remainder of the public were rarely restricted. The indoor tanning industry is known to downplay the risks of indoor tanning while emphasizing the supposed benefits, and many of their claims have been disproven.14 Limited regulation of these claims may contribute to misinformation about the hazards of indoor tanning. For example, 62% of indoor tanning users aged 12 and over have said that obtaining a base tan—a misleading claim used by indoor tanning salons—as the reason for their usage of these devices.11,33 The potential for misinformation does not end at the age of 18, and thus protection from misleading advertisements for all ages is necessary.

The ocular effects of indoor tanning are important to consider when regulating tanning facilities. Thus, it is a concern that less than half of provinces and territories with indoor tanning legislation require clients to use protective eyewear. The federal RED Regulations require protective eyewear with certain specifications to be included with indoor tanning equipment sold in Canada, but do not contain provisions for client use of this eyewear.20 The provinces and territories must shoulder some responsibility to ensure that clients are adequately protected by eyewear while tanning.

The RED Regulations require tanning device manufacturers to label each piece of equipment with the recommended exposure schedule, yearly maximum exposure time and minimum interval between indoor tanning sessions.20 However, no provinces or territories had legislation mandating that these recommendations must be followed, despite Health Canada’s Guidelines for Tanning Salon Owners, Operators, and Users, which state that the first and maximum exposure times on these labels are not to be exceeded.6 There appears to be a gap between federal and provincial legislative coverage in all jurisdictions, despite evidence suggesting a dose–response relationship between indoor tanning and skin cancer.5,34 The extent to which indoor tanning facilities are following these recommendations is unclear, though 18% of indoor tanning users have reported not following the exposure schedule recommended by manufacturers.11 This is also a concern since only four provinces/ territories prohibit unsupervised use of indoor tanning equipment and only three mention operator training in the legislation. Thus, there may be more opportunities for the misuse of these devices. To reduce risks to clients, WHO advises against the use of unsupervised tanning equipment and recommends the presence of an operator who is trained in procedures such as recognizing clients’ personal risk factors and emergency protocols.8

Legislative impact can only be maximized through comprehensive enforcement protocols by authorities and compliance by salon operators. All provinces and territories require inspections for compliance and outline specific penalties, which may help to deter tanning facility operators from violating the legislation. However, the legislation in most provinces/territories does not mention how often indoor tanning facilities must be inspected for compliance. In those provinces and territories that do state a frequency, only one is specific. In a study of 3647 indoor tanning facilities in the USA, Pichon et al. found that facilities were more likely to comply with youth access restrictions if there were frequent inspections.35 Regular inspections may therefore have an impact on compliance with indoor tanning legislation and should be outlined in more detail in provincial and territorial laws.

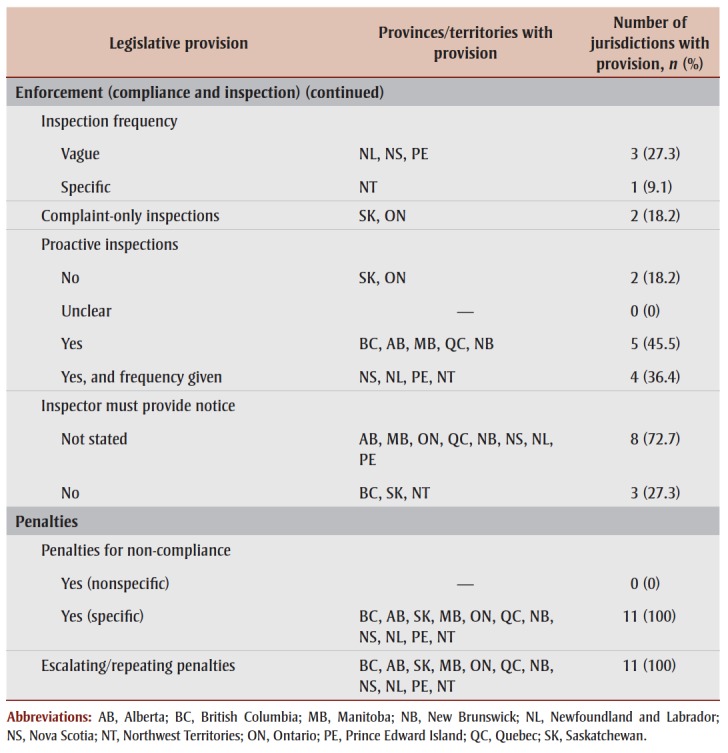

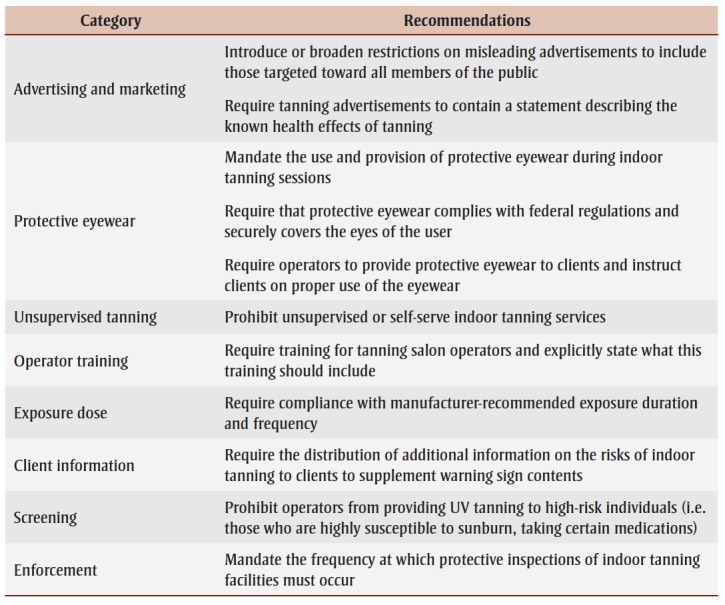

Based on legislative gaps that we have identified in our analysis, we provide recommendations for provincial and territorial governments (Table 4). In addition, we recommend that the federal government issue an evidence-based document to inform provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation. This may help provinces and territories incorporate additional, evidence-based regulations or strengthen existing ones. We acknowledge that additional evidence would make these recommendations more robust.

Table 4. Recommendations for provincial and territorial governments for more comprehensive indoor tanning legislation.

|

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first comprehensive analysis of provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation in Canada. By incorporating laws, regulations and supplementary information, we have conducted a content analysis that is significant in both breadth and depth. This enabled us to highlight areas of strong coverage, as well as limitations within each jurisdiction and across Canada. This research lays the necessary foundation for future comparisons and evaluations and provides policy stakeholders with the information necessary to investigate effectiveness and advocate for improved legislative coverage. It also provides provincial and territorial authorities with detailed information about the landscape of indoor tanning legislation across the country, which may motivate legislative improvements and, ultimately, gold standard legislation.

Though the enforcement content of the legislation was analyzed in this study, the actual enforcement practices were not included because published enforcement data were not readily available at the time of writing. In order for true legislative effectiveness to be examined, future research should investigate the practices of enforcement authorities with respect to indoor tanning legislation. Compliance with the legislation was also not measured in this study. If compliance with the provincial and territorial legislation is low, these laws will not be effective. Indeed, there is evidence from the USA that compliance with some aspects of indoor tanning legislation (labelling, risk communication, false claims) is low.33,36 To accurately measure the effectiveness of indoor tanning legislation, it is important to investigate compliance in each province and territory. For example, mixed results have been found regarding the success of the provincial indoor tanning legislation in Ontario.37

One of the challenges of this research was interpreting the legal language. It has been said that “the law is a profession of words” and, as such, the meaning of words within legal documents is sometimes ambiguous in the same way they can be in other contexts.38 Although we addressed ambiguity in legal language by consulting with public health and policy experts and health authorities in some of the jurisdictions studied, there may be alternative interpretations.

Future research

It would be helpful to have an objective, numerical method for between-jurisdiction comparisons of indoor tanning legislative coverage. The results of this content analysis could inform the development and validation of a scoring tool for Canadian provincial/territorial indoor tanning legislation, similar to those introduced by Gosis et al. and Woodruff et al.22,23 The scores may also be useful in determining whether higher legislative coverage, indicated by a higher score, corresponds to higher levels of compliance and enforcement, and lower prevalence of use, especially among youth.

Though this research focused on provincial and territorial legislation, analyses of indoor tanning bylaws should also be conducted. This will provide valuable information on what is being covered by municipalities and allow for comparisons between these bylaws and provincial and territorial legislation. While collecting legislation for this analysis, we found indoor tanning bylaws in British Columbia (Capital Regional District), Ontario (Region of Peel, Mississauga, Brampton, Oakville, Belleville) and Yukon (Whitehorse). Because the bylaws in these municipalities may contain different provisions than their respective provinces, it is important their content be analyzed in future work.

Conclusion

All Canadian provinces and one of three territories have enacted legislation to regulate the operation of indoor tanning facilities. This represents an encouraging response by governments to the research on the health risks of this activity and related public health recommendations. Most of these laws focus on youth. Legislative coverage of warning sign requirements, penalties, advertising directed toward youth and inspection requirements were also strong. Good first steps have been made in terms of legislation to protect Canadians from skin cancer and other health effects related to indoor tanning, but amendments in some areas could protect the public more effectively. We recommend more legislative attention in the areas of client information, client protection (e.g. protective eyewear, screening of high-risk clients and restrictions on duration and frequency of use), advertising in general (especially health claims) and inspection frequency to ensure that Canadians are well-protected and facilities are following the law.

The results of this study provide policy stakeholders with a detailed overview of the current state of indoor tanning laws across Canada, including how the content of this legislation varies across the country, as well as legislative areas that are receiving high coverage and areas where increased legislative efforts may be needed. Combined with future research needed to determine compliance with, and impact of, indoor tanning legislation, this research contributes to a clearer picture of indoor tanning legislation and activity in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific funding. SG is supported through the University of Guelph’s OVC MSc Scholarship and Graduate Tuition Scholarship, as well as a Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions and statement

Both authors contributed substantially to the design of the research study, the acquisition and analysis of the data and writing the paper. SG contributed most significantly to data acquisition and drafting the paper. JEM contributed most significantly to the study design and analysis, and in revising the paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. Toronto(ON): 2014. Canadian cancer statistics 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Toronto(ON): 2017. Canadian cancer statistics 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Lyon(FR): 2012. A review of human carcinogens part D: radiation. [Google Scholar]

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, Han J, Qureshi AA, Linos E, et al. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012:e5909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniol M, Autier P, Boyle P, Gandini S, et al. Cutaneous melanoma attributed to sunbed use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012:e4757. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2014. Guidelines for tanning salon owners, operators, and users. [Google Scholar]

- Lim HW, James WD, Rigel DS, Maloney ME, Spencer JM, Bhushan R, et al. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation from the use of indoor tanning equipment: time to ban the tan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64((4)):e51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair C, et al. Artificial tanning sunbeds: risks and guidance. Sinclair C. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich SE, et al. Mechanisms underlying UV-induced immune suppression. Mutat Res. 2005;571((1-2)):185–205. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays D, Atkins MB, Ahn J, Tercyak KP, et al. Indoor tanning dependence in young adult women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26((11)):1636–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qutob S, O’Brien M, Feder K, et al, et al. Tanning equipment use: 2014. Qutob S, O’Brien M, Feder K, et al [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Toronto(ON): 2009. Canadian cancer statistics 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McWhirter JE, Hoffman-Goetz L, et al. Skin deep: coverage of skin cancer and recreational tanning in Canadian women’s magazines (2000-2012) Can J Public Health. 2015;106((4)):e236–e243. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman JM, Fisher DE, et al. Indoor UV tanning and skin cancer: Health risks and opportunities. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21((2)):144–9. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283252fc5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GP Jr, Berkowitz Z, Jones SE, et al, et al. State indoor tanning laws and adolescent indoor tanning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104((4)):e69–74. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert A, Cornuz J, et al. Which are the most effective and cost-effective interventions for tobacco control. Gilbert A, Cornuz J. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Mackay J, Eriksen MP, et al. Myriad Editions. Brighton(UK): 2002. The tobacco atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Achievements in public health, 1900-1999 motor-vehicle safety: a 20th century public health achievement. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. :369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radiation Emitting Devices Act, R.S.C. C. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/R-1/ [Google Scholar]

- Radiation Emitting Devices Regulations, C.R.C., c.1370. Government of Canada. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.%2C_c._1370/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Province of Manitoba. Winnipeg(MB): Manitoba Laws (Internet) Available from: http://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/index.php. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff SI, Pichon LC, Hoerster KD, Forster JL, Gilmer T, Mayer JA, et al. Measuring the stringency of states’ indoor tanning regulations: instrument development and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56((5)):774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosis B, Sampson BP, Seidenberg AB, Balk SJ, Gottlieb M, Geller AC, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of indoor tanning regulations: a 50-state analysis, 2012. Gosis B, Sampson BP, Seidenberg AB, Balk SJ, Gottlieb M, Geller AC. 2014:620–27. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joossens L, Raw M, et al. The Tobacco Control Scale: a new scale to measure country activity. Tob Control. 2006:247–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, et al, et al. A new scale of the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46((1)):10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Wechsler H, et al. The state sets the rate: the relationship among state-specific college binge drinking, state binge drinking rates, and selected state alcohol control policies. Am J Public Health. 2005;95((3)):441–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanney MS, Nelson T, Wall M, et al, et al. State school nutrition and physical activity policy environment and youth obesity. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38((1)):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Perna FM, Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Weight status among adolescents in states that govern competitive food nutrition content. Pediatrics. 2012;130((3)):437–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slapin JB, Proksch S, Martin S, Saalfield T, Strom KW, et al. Words as data: content analysis in legislative studies. Slapin JB, Proksch S. Available from: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199653010.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199653010. [Google Scholar]

- Census Profile. Ottawa(ON): Nunavut (Territory) and Canada (Country) (table) Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=62&Geo2=&Code2=&Data=Count&SearchText=Nunavut&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=62. [Google Scholar]

- Census Profile. Ottawa(ON): Yukon (Territory) and Canada (Country) (table) Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=60&Geo2=&Code2=&Data=Count&SearchText=Yukon&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=60. [Google Scholar]

- City of Whitehorse Personal Services Bylaw 95-56 (14 Nov 1995) City of Whitehorse. Available from: https://www.whitehorse.ca/home/showdocument?id=88. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SK, Haas AF, Pletcher MJ, JS Jr, et al. Compliance by California tanning facilities with the nation’s first statewide ban on use before the age of 18 years. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69((6)):883–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Qureshi AA, Geller AC, Frazier L, Hunter DJ, Han J, et al. Use of tanning beds and incidence of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30((14)):1588–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon LC, Mayer JA, Hoerster KD, et al, et al. Youth access to artificial radiation exposure: Practices of 3,647 U.S. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145((9)):997–1002. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouse CH, Basch CE, Neugut AI, et al. Warning signs observed in tanning salons in New York City: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8((4)):A88–1002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadalin V, Marrett L, Cawley C, et al, et al. Assessing a ban on the use of UV tanning devices among adolescents in Ontario, Canada: first-year results. Can J Public Health. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellinkoff D, et al. Little, Brown & Co. Boston(MA): 1963. The language of the law. [Google Scholar]