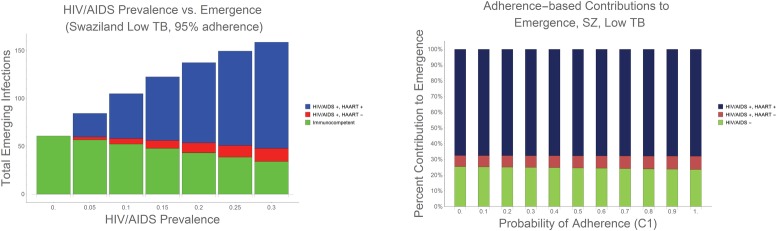

Fig 3. Emergence as a functions of increasing HIV/AIDS prevalence and adherence.

3a. In Using Swaziland’s low TB condition as an example, and assuming 95% antibiotic adherence [25], we found that, as HIV/AIDS prevalence increases from zero to 30%, we observe a corresponding increase in expected population-wide emergence of antibiotic resistance. Our conservative estimate of 20% antibiotic adherence represents a best-case scenario in terms of expected emergence; however, the likelihood of emergence becomes greater as adherence decreases. [26] 3b. Within the developing world, economic, medical and social barriers can limit antibiotic adherence. [26] To measure the impact of antibiotic adherence on emerging resistance within HIV/AIDS prevalent environments, we varied the probability of complete adherence (represented as C1 in the model) from 0–100%, while maintaining the original adherence ratios reported in the literature [25, 27] (see S1 Appendix). We use Swaziland’s low TB condition for purposes of illustration, however, we note that the results for Swaziland’s high TB, as well as both the low and high TB conditions in Indonesia, mirror the results presented: antibiotic adherence has very little impact on the emergence of resistance in HIV/AIDS-immunocompromised host populations, relative to the impact of HIV/AIDS prevalence.