Abstract

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) has been used in addition to radical surgery for primary and secondary pleural malignancies to improve local control, prolong survival, and improve the quality of life. This study was performed to study the indications, methodology, perioperative outcomes, and survival in patients undergoing HITHOC at Indian centers. A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected demographic and clinical data, perioperative and survival data of patients undergoing surgery with or without HITHOC was performed. From January 2011 to May 2018, seven patients underwent pleurectomy/decortication (P/D) or extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) with HITHOC and four had P/D or EPP alone at three Indian centers. P/D was performed in two and EPP in nine patients. The primary tumor was pleural mesothelioma in eight, metastases from thymoma in one, germ cell tumor in one, and solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura in one. HITHOC was performed using cisplatin. Grade 3–4 complications were seen in one patient in the HITHOC group and none in the non-HITHOC group, and one patient in the non-HITHOC group died of complications. At a median follow-up of 9 months, five patients of the HITHOC group were alive, four without recurrence, and one with recurrence. One patient in the non-HITHOC group was alive and disease-free at 24 months, and two died of progression at 18 and 36 months. HITHOC can be performed without increasing the morbidity of P/D or EPP. Most of these patients require multimodality treatment and are best managed by multidisciplinary teams.

Keywords: Pleural mesothelioma, HITHOC, Pleural metastases

Introduction

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) has been used in addition to radical surgery for primary and secondary pleural malignancies to improve local control, prolong survival, and improve the quality of life [1]. The common tumors treated with this modality are malignant pleural mesothelioma, pleural metastases from thymoma and thymic carcinoma, and occasionally metastases from lung and ovarian cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) [2, 3]. With the increasing popularity of HIPEC for the treatment of peritoneal metastases, some surgeons who treat both pleural and peritoneal metastases have started performing HITHOC. This study was performed to study the indications, methodology, perioperative outcomes, and survival in patients undergoing HITHOC at Indian centers.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data was performed. Indian surgeons who are part of the Indian Network for Development of Peritoneal Surface Oncology and perform HITHOC were approached.

The demographic and clinical data, perioperative outcomes including the surgical details and HITHOC methodology, and survival data were collected and analyzed.

Patient Selection and Preoperative Assessment

Patients undergoing pleurectomy/decortication (P/D) or extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) with or without HITHOC for any indication were included. The preoperative workup included, in addition to routine investigations, a CT scan of the thorax and abdomen or a PET-CT scan. Histological confirmation of the primary disease on biopsy and immunohistochemistry where required was performed for all patients.

Patients were excluded in case of bulky mediastinal involvement, extra-thoracic (abdominal) extension of disease, massive infiltration of the lung, or sarcomatoid histology (last two are specific for mesothelioma). Patients with mesothelioma having focal chest wall involvement were included but those with diffuse involvement were excluded from surgery. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical (VATS) was performed to evaluate the disease extent in selected patients. Pulmonary function tests (static and dynamic volumes both) and arterial blood gas analysis were performed for all patients. The cardiac workup included echocardiography. The symptoms of each patient were carefully evaluated: the procedure and its risks and benefits were explained. Patients with a predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in 1 second lower than 50% were excluded from surgery. This prediction is made without the use of a ventilation–perfusion scan.

Surgical Procedures

The surgical procedures performed along with HITHOC included P/D and EPP. A thymectomy was performed for patients with a thymoma or thymic carcinoma with the primary in situ, mediastinal lymphadenectomy for patients with enlarged nodes, and segmental/lobar lung resection in patients with a primary arising from the lung. The extent of pleural resection depended on the indication for the procedure. For secondary metastatic disease, only the involved pleura was removed.

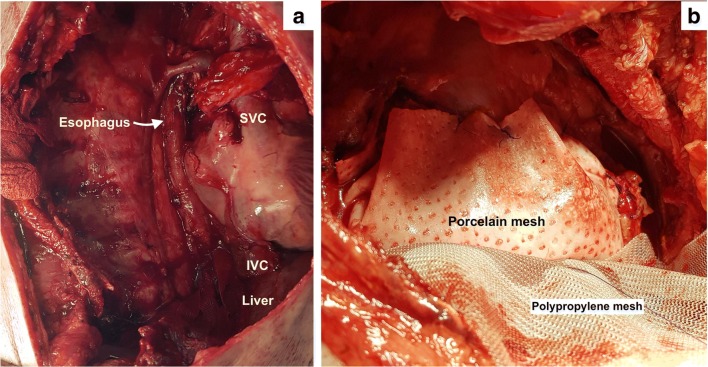

For pleural mesothelioma, the entire parietal pleura is removed and the visceral pleura as much as possible. Where the lung tissue is infiltrated, segmental resection is performed. When the diaphragm is infiltrated, resection of the diaphragm is performed. For patients with multiple sites of visceral pleural involvement, it may be considered impossible to remove all disease sites. In this situation, some surgeons prefer to perform an EPP to completely remove the disease [4]. When disease is found in any region of the visceral pleura, all fissures should be explored for the presence of disease. When multiple lung segments need to be resected, an EPP is indicated. Resection of the diaphragm is part of EPP; however, resection of the pericardium is at the discretion of the treating surgeon. When the pericardium has been removed, it is reconstructed using a porcelain or gortex mesh before performing HITHOC (Fig. 1). Reconstruction of the diaphragm may be performed before or after. Due to the ligaments of the liver, loss of perfusate into the peritoneal cavity does not occur on the right side, though seepage is unavoidable and will not be prevented by reconstructing the diaphragm before the procedure on either side. A gortex or polypropylene mesh is used to reconstruct the diaphragm.

Fig. 1.

a Thoracic cavity after EPP with resection of the pericardium and the diaphragm. b Reconstruction of the pericardium with a porcelain mesh and diaphragm with a polypropylene mesh

Surgical Technique of EPP

EPP involves en bloc resection of the lung, pleura, pericardium, and diaphragm with radical lymph node dissection followed by patch reconstruction of the diaphragm and pericardium [5].

It is performed through a posterolateral thoracotomy. The pleural space is not opened. Resection of one or more ribs may be performed. The apical dissection is performed first followed by identification of the mediastinal structures posteriorly. The azygous vein serves as a landmark for identifying the esophagus. The superior vena cava, aorta, esophagus, and trachea are identified and safeguarded. Involvement of any of these structures is a sign of inoperability. The phrenic nerve is identified and preserved if possible. Focal involvement of the mediastinal fat and involvement of the mediastinal pleura may still be considered for surgery if negative margins can be obtained. The thoracic duct, if identified, is ligated to prevent a postoperative chyle leak. It is not always necessary to look for it, but the surgeon must be cautious in dissection around the lower end of the intrathoracic esophagus on the right side. The two regions that require particular mention are resection of the diaphragm and that of the pericardium. After retracting the tumor and the lung away, the pericardial sac is opened anteriorly. Involvement is determined by palpation. Involvement of the pericardium is not a sign of inoperability but involvement of the myocardium is. The two pulmonary veins, pulmonary artery SVC and IVC, should all be identified before ligating any structure. The pulmonary artery and veins are divided intrapericardially using endostaplers. The junction of vena cava with the right atrium and the hepatic veins that are in close proximity need to be identified and safeguarded. The phrenic veins entering into the IVC should be identified and divided. Failure to do so may lead to inadvertent injury and intra-abdominal bleeding which can become difficult to control.

It is best to begin resecting the diaphragm laterally. It is divided at its lateral attachment to the chest wall with electrocautery and in that region from the peritoneum by blunt dissection. Moving medially, the peritoneum is entered to identify and safeguard the hepatic veins and the IVC as it enters the thoracic cavity. The peritoneum is left widely open. When the diaphragmatic resection reaches the posterior mediastinum, the IVC and esophageal hiatus should be well visualized in the operative field.

Right-Sided Versus Left-Sided EPP

There is a greater risk of thoracic duct injury for a right-sided EPP and greater risk of arrhythmias in a left-sided EPP—especially VF. On the left side, the pleura over the aortic arch and descending aorta are densely adherent and difficult to remove.

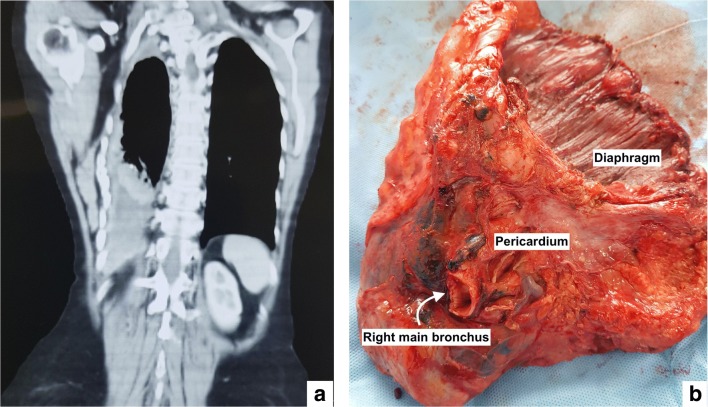

HITHOC

HITHOC is performed using a home-made or custom-made hyperthermia pump keeping the thoracic cavity open or closed (Fig. 2). One or two inflow channels and one or two outflow channels are used to perform the perfusion. The target intrathoracic temperature is 41–43 °C. The perfusion is performed for 60–90 min. Cisplatin is used either as a single agent at 100–150 mg/m2 or in combination with adriamycin 60–100 mg or mitomycin C 15 mg [6–8]. The carrier solution is 1.5% peritoneal dialysis fluid, and the volume of the perfusate depends on the volume of the thoracic cavity which varies greatly depending on the sex and built of the patient but is on average 2–2.5 l. Two to three intrathoracic temperature probes are used to monitor the temperature.

Fig. 2.

HITHOC being performed by the open method. The skin edges are hitched and sutured to a table mounted retractor, and the edges of the thoracic wall are constantly kept submerged in fluid to allow adequate perfusion

Perioperative Management

Preoperative hydration is performed depending on the preference of the treating team using normal saline 1 ml/kg/h for 12–24 h before the scheduled surgical procedure mainly for renal protection.

Unlike HIPEC, there are no guidelines for intraoperative fluid management and most teams prefer goal-directed fluid therapy. The monitoring of blood gases, temperature, and urine output during the HITHOC is similar to that during HIPEC. During chemotherapy perfusion, one lung ventilation is performed keeping the operative side only partially ventilated or a continuous positive airway pressure with a PEEP of 5–10 mmHg is used to allow acceptable oxygenation and sufficient space between the chest wall and pulmonary parenchyma. Continuous monitoring of the core body temperature is performed and if required, active external cooling is done.

There is a risk of intraoperative cardiac events especially when the pericardium has been removed. Defibrillating paddles are deployed in position throughout the procedure to deal with the same. Patients are extubated immediately after surgery as far as possible. Each patient is managed in the intensive care for a minimum of 24 h.

Morbidity and Mortality

Complications are graded using the NCI-CTCAE version 4 [9]. As for HIPEC, the 30- and 90-day morbidity and mortality were both recorded.

Adjuvant Therapy and Follow-up

The decision for adjuvant therapy is taken in the multidisciplinary team. Follow-up is done every 3 months and comprises of clinical examination, blood investigations, and imaging as clinically indicated. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) are calculated from the day of surgery.

Results

From January 2011 to May 2018, seven patients underwent P/D or EPP HITHOC and four had P/D or EPP alone at three Indian centers. Till 2015, only P/D or EPP was performed.

HITHOC Patients

The median age was 48 years (range 24–60 years). Five patients were male and two were female. The primary site was a pleural mesothelioma in five patients, metastases from thymoma in one patient, and a solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura in one patient. Four patients had EPP and three had P/D. Thymectomy was performed in the patient with thymoma by the minimally invasive approach followed by P/D and HITHOC. Further surgical details are provided in Table 1. All patients had HITHOC with cisplatin as a single agent by the open method.

Table 1.

Surgical procedures and morbidity in patients undergoing HITHOC

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/sex | 53/M | 44/M | 56/M | 24/M | 60/F | 40/F | 56/M |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 18 | 18 | 36 |

| Preoperative performance status | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 (improved) | 2 (improved) | 1 |

| Histology | Desmoplastic | Epitheloid | Epitheloid | Thymoma | Biphasic | Epitheloid | Solitary fibrous tumor |

| Prior chemotherapy/NACT | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Surgery | P/D | EPP | EPP | P/D | EPP | EPP | EPP |

| Lung infiltration | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chest wall infiltration | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Mediastinal pleura involvement | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Mediastinal infiltration | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Mediastinal lymph nodes dissected | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Diaphragm resection | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pericardial resection | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Operative time (min) | 260 | 465 | 430 | 240 | 420 | 775 | 420 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 500 | 2300 | 1400 | 700 | 800 | 2500 | 400 |

| Intraoperative complication | No | Yes | No | No | No | no | No |

| Postoperative ventilation | 18 h | No | No | No | 41 h | 42 h | 36 h |

| Grade 3–4 morbidity | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 90-day mortality | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Follow-up (months) | 24 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 24 |

| Progression free survival (months) | 8 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 24 |

| Overall survival (months) | 24 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 24 |

| Site of recurrence/progression | Intrathoracic | Disease free | Disease free | Disease free | Death due to other causes | Chest wall | Disease free |

Three patients required mechanical ventilation for 12–14 h postoperatively. The blood loss ranged from 500 to 2300 ml. The mean operative time was 380 min.

Morbidity

Intraoperative arrhythmias developed in two patients and were treated with IV drugs. No systemic or renal toxicity was observed in any of the patients. One patient had acute coronary syndrome which required return to the ICU and prolonged hospitalization.

Systemic Chemotherapy

One patient received preoperative chemotherapy with cisplatin and pemetrexed and completed adjuvant chemotherapy as well (Table 1). Four others were advised adjuvant chemotherapy of which one patient was not able to undergo chemotherapy, and three completed the full course. One patient received adjuvant radiotherapy and in others, it was not planned.

Survival Outcomes

The median follow-up was 9 months. Four patients were disease-free. Two developed recurrence at 6 and 8 months, respectively, and one patient died of unrelated causes at 6 months. One patient died of progressive disease. At the last follow-up, five others were alive—one with and four without disease. Two patients, who had severe pain before and ECOG status of 3 and 2, experienced an improvement in their symptoms and performance status.

Patients Who Did Not Undergo HITHOC

There were four patients in this group, and it represents the early experience of the first author. Three patients had pleural mesothelioma, and one had a germ cell tumor. The patient and disease characteristics and perioperative and survival outcomes are provided in Table 2. All patients had resection of the pericardium and diaphragm. There was one postoperative death in this group due to ventricular fibrillation. One patient is disease-free at 24 months. One patient developed recurrence at 24 months and died after 36 months of surgery. Another patient died after 18 months of surgery.

Table 2.

Findings in patients undergoing surgery without HITHOC

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/sex | 21/M | 46/F | 60/M | 55/M |

| Surgery | EPP | EPP | EPP | EPP |

| Lung infiltration | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chest wall infiltration | No | No | No | No |

| Mediastinal pleura involvement | Yes | No | No | No |

| Mediastinal infiltration | No | No | No | No |

| Mediastinal lymph nodes dissected | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Diaphragm resection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pericardial resection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Operative time (min) | 540 | 500 | 480 | 470 |

| Intraoperative complication | Ventricular fibrillations | No | No | No |

| Postoperative ventilation | Yes | No | No | No |

| Grade 3–4 morbidity | No | No | No | No |

| 90-day mortality | Yes | No | No | No |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Preoperative performance status | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Histology | Non-seminoma germ cell tumor | Epitheloid | Epitheloid | Epitheloid |

| Prior chemotherapy/NACT | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | No | For recurrence | No | No |

| Follow-up (months) | 0 | 36 | 24 | 12 |

| Progression-free survival (months) | 0 | 24 | 24 | NA |

| Overall survival (months) | 0 | 36 | 24 | 18 |

| Site of recurrence/progression | Disease free | Mediastinal lymph nodes | Disease free | NA |

NA not available

Discussion

Despite the small numbers, out results show that HITHOC can be performed without adding to the morbidity of P/D and EPP. The numbers are very small and follow-up short to comment on survival, but the results correlate with the survival obtained in published reports [10–12].

The physiological changes due to massive third space fluid loss, metabolic derangements, systemic toxicity, and bowel complications that are common in patients undergoing HIPEC are not seen after HITHOC.

The physiology of the thoracic cavity is different from the peritoneal cavity. The systemic absorption of the chemotherapeutic agent from the pleural space is roughly half of what occurs from the peritoneal space, and hence, a much higher dose of cisplatin is used for HITHOC. This was demonstrated in a pharmacokinetic study by Sugarbaker et al. which also showed that approximately 41 ± 3% of the total mitomycin C was absorbed systemically during the 90 min HITHOC, and there was a considerably more rapid clearance of the drug from the abdomen as compared to that from the thorax [13].

And unlike the bowel that is prone to complications following HIPEC, even when the lung is not resected, there is no toxicity specific to the direct application of heated chemotherapy. The morbidity of the surgery is the morbidity of the P/D or EPP. EPP itself can lead to severe medical and surgical complications and requires multidisciplinary expertise for both prevention and management [14]. In a meta-analysis of 21 studies for pleural mesothelioma, the authors found that while surgery may cause complications like bronchopleural fistula, diaphragm rupture, or laryngeal nerve dysfunction, HITHOC itself did not cause such adverse effects [15]. A review of HITHOC performed at German thoracic surgery centers also found a low rate of major complications [16].

Liu et al. have devised a method for performing HITHOC at the bedside, thus making repeated applications possible. In their experience in 1510 such procedures performed in 315 patients, there was no mortality and morbidity in 2% of the patients [17].

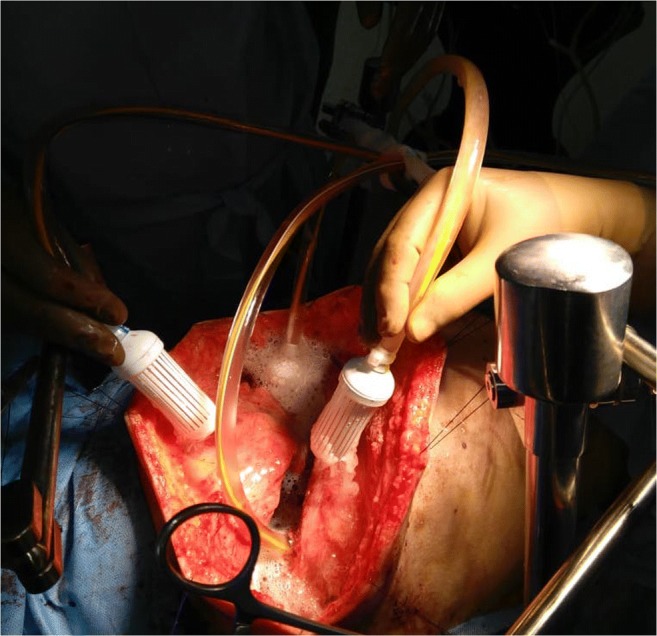

In this series, there was one postoperative death in the non-HITHOC group and none in the HITHOC group and only one patient experienced major morbidity. The patient developed ventricular fibrillations which are more common with left-sided procedures. The HITHOC and non-HITHOC groups are not strictly comparable. In the HITHOC group, two patients with more aggressive disease (like chest wall and mediastinal involvement) were taken up for surgery (Fig. 3). Both these patients were severely symptomatic from the disease and incapacitated due to it. Surgery was performed for symptom control and improvement in the performance status which was achieved in both. However, both developed a recurrence within 6 months of surgery. The median follow-up in the HITHOC group is 9 months compared to 24 months in the other group which makes it difficult to comment on the survival difference.

Fig. 3.

Patient with advanced disease. a CT scan showing crowding of ribs and collapse of the lower half of the lung. b EPP in the same patient with en bloc resection of the pericardium and diaphragm

Looking at each of the diseases individually, the median survival in pleural mesothelioma is dismal. With multimodality treatment comprising of surgery with intrathoracic and systemic chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy, the median survival is still only 15–18 months and the median DFS under 12 months [15]. The therapy itself is intense, and many patients may not be able to withstand this aggressive treatment. This is important when the patient requires an EPP. It should be understood that in most patients, P/D and EPP are not alternatives but the decision to perform one over the other is based on the disease extent and distribution, the general condition of the patient, and the clinical experience of the multidisciplinary team [18]. The exact incidence of pleural mesothelioma in India is not known; however, there is no epidemic as in some other parts of the world and hence, misdiagnosis and mismanagement is still common [19]. Four of the eight patients with mesothelioma underwent surgery over 3 months after diagnosis. More than one treatment modality is needed for all stages of pleural mesothelioma since even a macroscopic complete resection is an R1 resection [20]. Most of the recurrences occur on the same side of the hemithorax [20]. All patients in whom adjuvant chemotherapy was planned were able to start it on time except one patient, and adjuvant chemotherapy was completed by all of them. Only one of the eight patients received adjuvant radiotherapy. The radiation oncologists were not familiar with adjuvant radiation for these patients which also had a bearing and the role of radiotherapy in addition to HITHOC is uncertain. The radiation fields are large after EPP, and probability of toxicity is high due to proximity of important structures. Patients with positive lymph nodes who need mediastinal radiation are the most difficult to radiate [20]. Sugarbaker et al. have proposed that patients who have node-positive disease should be treated with HITHOC, and radiation should be omitted in these patients [20]. The additional benefit of HITHOC over radical surgery alone has been demonstrated in a meta-analysis. HITHOC did not increase the morbidity of surgery and affect the patients’ ability to withstand further therapy. Another approach that has shown good results in some patients is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery and postoperative radiotherapy [21, 22]. Epitheloid histology is a major prognostic factor. In our experience, two patients had a sarcomatoid component in the postoperative histopathological evaluation which can be seen in 10% of the patients undergoing surgery [23].

We had only one patient of thymoma with pleural metastases and none with thymic carcinoma. Resection of pleural metastases with or without HITHOC has shown a survival benefit in thymoma [24, 25]. Patients with synchronous metastases have a better survival compared to those with metachronous disease [25]. The role in thymic carcinomas is less clear. HITHOC has demonstrated a benefit as a palliative therapy in patients with malignant pleural effusion [26].

For other indications, there are anecdotal reports of the use of HITHOC. One patient with a solitary fibrous tumor involving the pleura was taken up for surgery as it is a slow-growing tumor with a good long-term benefit. The benefit in patients with PMP can be extrapolated from that obtained in patients with peritoneal disease. For other indications, the decision should be individualized. Given the rarity of such situations, there will never be robust evidence for many indications. Multidisciplinary evaluation and assessment of risk versus benefit coupled with proper counselling of the same should all be part of the decision-making process.

Surgical treatment of pleural metastases comprises of complex surgical procedures that require specialized training and skill to perform.

Conclusions

HITHOC can be performed without increasing the morbidity of pleurectomy/decortication or extrapleural pneumonectomy in patients with primary and secondary pleural malignancies. Most of these patients require multimodality treatment and are best managed by multidisciplinary teams. In addition to prolonging survival, such therapy may be used for obtaining symptom control in selected patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ried M, Potzger T, Braune N, Neu R, Zausig Y, Schalke B, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy perfusion for malignant pleural tumours: perioperative management and clinical experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43(4):801–807. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro M, Korst RJ. Surgical approaches for stage iva thymic epithelial tumors. Front Oncol. 2014;3:332. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migliore M. Debulking surgery and hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) for lung cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2017;29(6):533–534. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.06.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao C, Tian D, Park J, Allan J, Pataky KA, Yan TD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical treatments for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2014;83:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DaSilva MC et al (2010) Technique of extrapleural pneumonectomy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 15(4):282–293

- 6.Rusch VW, Niedzwiecki D, Tao Y, Menendez-Botet C, Dnistrian A, Kelsen D, Saltz L, Markman M. Intrapleural cisplatin and mitomycin for malignant mesothelioma following pleurectomy: pharmacokinetic studies. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1001–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerza R, Esposito M, Vannozzi M, Bottino GB, Bogliolo G, Pannacciulli I. High doses of intrapleural cisplatin in a case of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer. 1994;73:79–84. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940101)73:1<79::AID-CNCR2820730115>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Department of Public Health and Hu- man Services, NIH, NCI: Common toxicity criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) (2010) National Cancer Institute. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE_Vers._4.03_2010–06-14;_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 31 Oct 2018

- 9.Tilleman TR, Richards WG, Zellos L, Johnson BE, Jaklitsch MT, Mueller J, Yeap BY, Mujoomdar AA, Ducko CT, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ. Extrapleural pneumonectomy followed by intracavitary intraoperative hyperthermic cisplatin with pharmacologic cytoprotection for treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a phase II prospective study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isik AF, Sanli M, Yilmaz M, Meteroglu F, Dikensoy O, Sevinc A, Camci C, Tuncozgur B, Elbeyli L. Intrapleural hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy in subjects with metastatic pleural malignancies. Respir Med. 2013;107:762–767. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Sandick JW, Kappers I, Baas P, Haas RL, Klomp HM. Surgical treatment in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a single institution’s experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1757–1764. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA, Eger C. Pharmacokinetics of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy following pleurectomy and decortication. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:471205. doi: 10.1155/2012/471205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collaud S, de Perrot M. Technical pitfalls and solutions in extrapleural pneumonectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1(4):537–543. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.11.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao ZY, Zhao SS, Ren M, Liu ZL, Li Z, Yang L. Effect of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy on the malignant pleural mesothelioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(59):100640–100647. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ried M, Hofmann HS, Dienemann H, Eichhorn M. Implementation of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (hithoc) in Germany. Zentralbl Chir. 2018;143(3):301–306. doi: 10.1055/a-0573-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L, Zhang N, Min J, Su H, Wang H, Chen D, Sun L, Zhang H, Li W, Zhang H. Retrospective analysis on the safety of 5,759 times of bedside hyperthermic intra-peritoneal or intra-pleural chemotherapy (HIPEC) Oncotarget. 2016;7:21570–21578. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao C, Tian D, Park J, Allan J, Pataky KA, Yan TD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical treatments for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer. 2014;83(2):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao S. Malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung India. 2009;26(2):53–54. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.48900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugarbaker DJ, Gill RR, Yeap BY, Wolf AS, DaSilva MC, Baldini EH, Bueno R, Richards WG. Hyperthermic intraoperative pleural cisplatin chemotherapy extends interval to recurrence and survival among low-risk patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma undergoing surgical macroscopic complete resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:955–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ried M, Potzger T, Sziklavari Z, Diez C, Neu R, Schalke B et al (2013) Extended surgical resections of advanced thymoma Masaoka stages III and IVa facilitate outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 10.1055/s-0033-1345303 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Weder W, Stahel RA, Bernhard J, Bodis S, Vogt P, Ballabeni P, Lardinois D, Betticher D, Schmid R, Stupp R, Ris H, Jermann M, Mingrone W, Roth A, Spiliopoulos A, On behalf of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research Multicenter trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1196–1202. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krug LM, Pass HI, Rusch VW, Kindler HL, Sugarbaker DJ, Rosenzweig KE, Flores R, Friedberg JS, Pisters K, Monberg M, Obasaju CK, Vogelzang NJ. Multicenter phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed lus cisplatin followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy and radiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3007–3013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakas A, Black E, Entwisle J, Muller S, Waller DA. Surgical assessment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: have we reached a critical stage? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1457–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belcher E, Hardwick T, Lal R, Marshall S, Spicer J, Lang-Lazdunski L. Induction chemotherapy, cytoreductive surgery and intraoperative hyperthermic pleural irrigation in patients with stage IVA thymoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12(5):744–747. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.255307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yellin A, Simansky DA, Ben-Avi R, Perelman M, Zeitlin N, Refaely Y, et al. Resection and heated pleural chemoperfusion in patients with thymic epithelial malignant disease and pleural spread: a single-institution experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou H, Wu W, Tang X, Zhou J, Shen Y. Effect of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) on the malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(1):e5532. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]