Abstract

Objectives

The proportion of women engaged in clinical research has increased over time. However, it is unclear if women and men contribute to the same extent during the conduct of research and, if so, if they are equally rewarded by a strategic first or last author position. We aim to describe the prevalence of women authors of original articles published 15 years apart and to compare the research contributions and author positions according to gender.

Design

Repeated cross-sectional study.

Setting

Published original articles.

Participants

1910 authors of 223 original articles published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2000 and 2015.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

Self-reported contributions to 10 aspects of the article (primary) and author position on the byline.

Results

The proportion of women authors increased from 32% (n=243) to 41% (n=469) between 2000 and 2015 (p<0.0001). In 2000, women authors were less frequently involved than men in the conception and design (134 (55%) vs 323 (61%); p=0.0256), critical revision (171 (70%) vs 426 (81%); p=0.0009), final approval (196 (81%) vs 453 (86%); p=0.0381) and obtaining of funding (39 (16%) vs 114 (22%); p=0.0245). Women were more frequently involved than men in administration and logistics (85 (35%) vs 137 (26%); p=0.0188) and data collection (121 (50%) vs 242 (46%); p=0.0532), but they were similarly involved in the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, provision of materials/patients and statistical expertise. Women were less often last authors than men (22 (9%) vs 82 (16%); p=0.0102). These gender differences persisted in 2015.

Conclusions

The representation of women among authors of medical articles increased notably between 2000 and 2015, but still remained below 50%. Women’s roles differed from those of men with no change over time.

Keywords: gender, publication, research, authorship

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used all original articles and reviews published in 2000 and 2015 in a single, widely cited USA-based medical journal that provides a constant and standard format for reporting author contributions in contrast to other medical journals that do not report author contributions in a consistent way over time.

We assessed 10 self-reported contributions of all authors of the selected original articles papers by gender 15 years apart.

We compared the authors’ position on the byline by gender 15 years apart after adjustment for their self-reported contributions.

We did not obtain information on the authors’ age, past experience in research, professorial rank, medical specialty and primary scientific discipline, which may all contribute to gender differences in specific research roles and this may decrease the interpretation of findings.

Introduction

Over the past decades, the proportion of women in medical sciences has increased worldwide.1–5 This demographic change should be associated in theory with a higher representation of women authoring scientific publications.6 In principle, women should make equivalent contributions to research and have the same opportunity to lead research projects as men. Furthermore, we should observe increased numbers of women at academic leadership positions.5 However, the chances of succeeding in research and obtaining a senior position are not the same for men and women with similar competencies.7 Women face also more difficulties than men in finding a mentor to help them manage their careers and facilitate their advancement and productivity.7 8 Finally, women scientists are less likely than men to get funded or to coauthor scientific publications.9 A recent publication demonstrated that the contributionship differed between female and male authors of articles published in journals from the Public Library of Science (PLoS).10

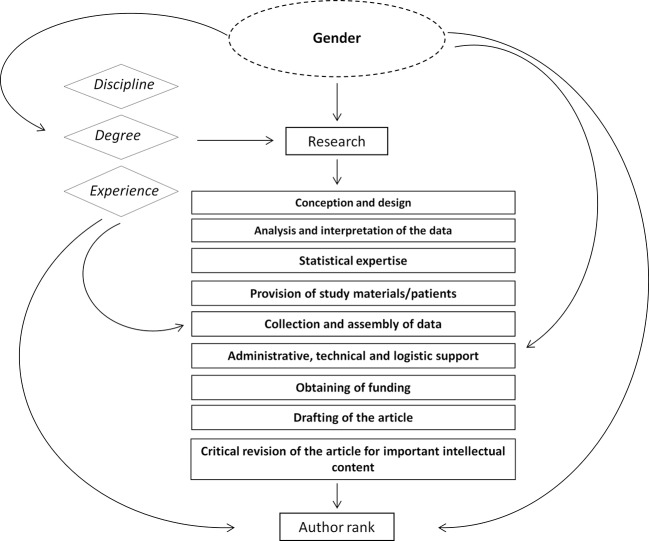

Currently, we do not fully understand how gender differences in indicators of academic achievement occur. One possibility is that men and women researchers do essentially the same things, but are not rewarded equitably by grants, author roles or tenured positions. Alternatively, the roles of men and women researchers may be different due to different trajectories during their training, in which case, the unequal rewards would be merely a consequence of these different skills and contributions (figure 1). It is important to understand this, because remedial actions would not be the same for these two types of gender inequality. Many universities have implemented programmes to facilitate women’s careers in science in the past decades.9 11 The effectiveness of such programmes is usually assessed through the gender ratio of academic promotions. However, promotions reflect only a late outcome and we know little about changes in gender roles during the conduct of research.

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms explaining gender bias in the authorship of scientific publications.

To clarify these issues, we conducted a cross-sectional study of original articles published in the Annals of Internal Medicine 15 years apart. We selected this journal because it applies a standardised description of 10 possible roles of all authors and this description has remained stable over this time span, in contrast to other leading medical journals. Our main objective was to compare the scientific contributions to medical research of female and male authors at both time periods and to determine if gender differences that may have been present in 2000 have narrowed or disappeared by 2015. Our secondary objective was to compare the authorship position of female and male authors with similar contributions to the research project and again to assess if there was a change between 2000 and 2015.

Methods

As the study was only based on a review of data publicly available online, prior approval from our institutional review board was not required for this study.

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study of all original reports and reviews published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in two time periods: (1) from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2000 and (2) from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015. Consensus statements, guidelines, clinical case reports and opinion papers were excluded because the author contributions criteria list does not fully fit these papers. All authors of the original research papers were included in the study population.

Study variables

The main independent variables were the time period and author gender. We determined the gender of each author from their first names. If an author’s gender was unclear to us, we used an internet search to find photographs and/or bibliographical information on the author. If this search was unproductive, we looked up the common usage of the first name.

The main dependent variables were the 10 possible contributions to the research paper as published in the Annals: (1) conception and design; (2) analysis and interpretation of the data; (3) drafting of the article; (4) critical revision of article for important intellectual content; (5) final approval of the article; (6) provision of study materials or patients; (7) statistical expertise; (8) obtaining of funding; (9) administrative, technical or logistic support; and (10) collection and assembly of data. We also retrieved the author’s rank on the byline in five categories: first, second, middle, next-to-last and last positions. If there were four authors, the middle author position was omitted; if there were three authors, the next-to-last position was also omitted; when there were two authors, the second position was omitted. In the case of a joint first author, the second position was not considered. We compared the first, second, next-to-last and last positions to the middle rank.

Other variables collected at the author level were: degrees (MD or other medical degree such as MBBS or DO, with or without an additional Master’s degree or PhD; any PhD or other doctoral degree alone, such as ScD or JD; any Master’s degree alone), home institution (university, including public health schools; medical school or hospital; public agency; industry; foundation or other non-profit; contract research organisation or consulting firm, including individuals who gave only a street address), country/continent of affiliation (USA, Canada, Europe and other). Independent variables at the article level was the type of funding (industry funding and specific non-industry funding) and subject matter (disease, prevention/behaviour/education and research methods/medico-economics/work environment). For each article, variables were collected from the online publication by one of the investigators (AGA, AP or TP) following prespecified rules. Uncertainties were solved by discussion and consensus between investigators.

Sample size estimation

An initial analysis of authorship profiles used all papers published in 2015.12 For this analysis of time trends and gender, we added all papers published in 2000. The study had a >90% power to detect a difference in the prevalence of female authors of 10% (eg, 40% vs 50%), even in the presence of a design effect of 2 due to intra-article correlation of author gender.

Statistical analysis

We described data at the author level and at the article level. We presented the author characteristic, contribution to publication and position on the byline by gender and by year of publication (2000 and 2015). First, we tested if the proportion of women varied between 2000 and 2015 by means of a mixed-effects logistic regression model with author gender as the dependent variable, a random effect at the article level and fixed effect on the year of publication. Then we assessed if every author characteristic (degree, home institution, country/continent of affiliation) was associated with gender using three mixed-effects models as previously described (adding a fixed-effect on the author characteristic) and if each of these associations remained stable over time by including an interaction term between the year and the author characteristic. We compared the proportion of each subject matter between the 2 years using χ2 test.

We assessed the association and its evolution over time between gender and 10 specific contributions to research paper. We built 10 mixed-effects logistic regression models where the contribution was the dependent variable, the article was the random factor and gender was the main fixed factor. In each model, we included the year and an interaction term between the year and gender to assess change over time. Finally, we reassessed these associations after adjustment for academic degrees. We reported both univariate and multivariable ORs and 95% CI by the year of publication.

Finally, to identify if gender was associated with a specific position on the article byline, we performed four conditional logistic regression models where each article defined a cluster, with author position (eg, first vs middle rank) as the dependent variable and gender the main predictor. We included the year and an interaction term between the year and gender to assess if there was a change over time of the associations between gender and author position. Then we adjusted the models for the 10 authors’ contributions to research. We built four models, comparing the first, second, next-to-last and last position to middle position. In these models, articles with four or fewer authors were excluded from the analyses.

All analyses were performed using STATA V.IC 15 for Windows (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (two-sided).

Patient and public involvement

Our study was an investigator-oriented research. Consequently, patients were not involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures, nor in the study design, data collection and conduct of the study. Therefore, we did not attempt to disseminate the results to study participants as the study was based on publicly available data extracted from published articles. However, these results were presented and discussed at an academic level in a Swiss colloquium in internal medicine (SGAIM SSMIG SSGIM 1 June 2018, Basel, Switzerland) and at the European Congress of Epidemiology 2018 (Lyon, France).

Results

We included 223 research papers published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, 104 articles in 2000 and 119 in 2015 (53%). In total, 1910 authors were listed on the 223 papers, 771 in 2000 and 1139 in 2015 (60%). The average number of authors per article was 7.4 (SD 4.3; range 2–30) in 2000 and 9.6 (SD 5.4; range 2–29) in 2015. Thirty-six articles included four or fewer authors. The distribution of each subject matter did not vary between 2000 and 2015: articles related to diseases represented 83.7% of all articles in 2000 (n=87) compared with 80.7% in 2015 (n=96); articles related to prevention, behaviours or education represented 9.6% in 2000 (n=10) versus 7.6% in 2015 (n=9); articles related to research methods, work environment or medico-economic analyses represented 6.7% in 2000 (n=7) versus 11.8% in 2015 (n=14) (p=0.401).

Comparison of characteristics, contributions to research and position on the byline by gender in 2000 and 2015

The proportion of women among authors increased by 10% between 2000 and 2015 (243 (32%) vs. 469 (41%); p<0.0001; table 1). At the paper level, one article was written only by women authors in 2000 (1%) versus three articles in 2015 (3%); 17 articles were written only by men authors in 2000 (16%) versus 12 articles in 2015 (10%), and 86 articles had mixed women and men authors in 2000 (83%) versus 104 in 2015 (87%). In both years, women had an MD and/or PhD degree less frequently compared with men (table 1). Women did not differ from men regarding their home institution in both years. There were some minor differences in the country of affiliation between women and men. We did not find any change over time in the proportions of women and men by author characteristic (p>0.05 for all interaction tests).

Table 1.

Comparison of author and study characteristics by gender, stratified by the year of publication

| Variables | 2000 | 2015 | Change in gender differences over time (P value *) |

||||

| Women (n=243, 31.5%) |

Men (n=528) |

P value | Women (n = 469, 41.2 %) |

Men (n=670) |

P value | ||

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.17 | ||||

| MD | 92 (37.9) | 343 (65.0) | 120 (25.6) | 291 (43.4) | |||

| MD and PhD | 12 (4.9) | 56 (10.6) | 18 (3.8) | 88 (13.1) | |||

| MD and Master | 26 (10.7) | 35 (6.6) | 66 (14.1) | 109 (16.3) | |||

| PhD | 40 (16.5) | 59 (11.2) | 135 (28.8) | 113 (16.9) | |||

| Master | 30 (12.3) | 24 (4.6) | 85 (18.1) | 50 (7.5) | |||

| Other degree or no degree | 43 (17.7) | 11 (2.1) | 45 (9.6) | 19 (2.8) | |||

| Home institution, n (%) | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.66 | ||||

| University | 66 (27.2) | 110 (20.8) | 151 (32.2) | 192 (28.7) | |||

| Medical school or hospital | 132 (54.3) | 334 (63.3) | 221 (47.1) | 372 (55.5) | |||

| Public agency | 20 (8.2) | 31 (5.9) | 48 (10.2) | 55 (8.2) | |||

| Industry | 11 (4.5) | 29 (5.5) | 20 (4.3) | 21 (3.1) | |||

| Foundation or other non-profit | 8 (3.3) | 10 (1.9) | 21 (4.5) | 19 (2.8) | |||

| Contract research organisation or similar | 5 (2.1) | 10 (1.9) | 6 (1.3) | 5 (0.8) | |||

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (0.9) | |||

| Country/continent, n (%) | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.52 | ||||

| USA | 188 (77.4) | 347 (65.7) | 368 (78.5) | 466 (69.6) | |||

| Canada | 12 (4.9) | 23 (4.4) | 32 (6.8) | 58 (8.7) | |||

| Europe | 36 (14.8) | 99 (18.8) | 48 (10.2) | 100 (14.9) | |||

| Other | 7 (2.9) | 59 (11.2) | 21 (4.5) | 46 (6.9) | |||

*P value testing an interaction between each variable listed and the year in the assessment of gender differences.

Association between gender and contributions to research

Women were less likely than men to contribute to the conception and design, critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, final approval of the article and obtaining of funding, both in 2000 and 2015 (table 2). In contrast, women contributed more frequently than men to administrative, technical or logistic support and to the collection and assembly of data both in 2000 and 2015. We did not find any statistical interactions between gender and year of publication for each of the 10 contributions, that is, no evidence of gender roles changing over time. After adjustment for academic degrees (table 3), most gender differences were attenuated, which indicates that training explains part of the gender-related differences, except for statistical expertise. However, this adjustment showed also that women contributed significantly less to statistical expertise than men in 2000 and 2015.

Table 2.

Comparison of author contributions by gender, stratified by the year of publication

| Variables | 2000 | 2015 | Change in gender differences over time (P value *) | ||||

| Women (n=243, 31.5%) |

Men (n=528) |

P value | Women (n=469, 41.2%) |

Men (n=670) |

P value | ||

| Contributions in the paper, n (%) | |||||||

| Conception and design | 134 (55.1) | 323 (61.2) | 0.03 | 223 (47.6) | 372 (55.5) | 0.001 | 0.81 |

| Analysis and interpretation of the data | 176 (72.4) | 362 (68.6) | 0.78 | 342 (72.9) | 496 (74.0) | 0.22 | 0.58 |

| Drafting of the article | 110 (45.3) | 206 (39.0) | 0.35 | 222 (47.3) | 298 (44.5) | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content | 171 (70.4) | 426 (80.7) | <0.001 | 317 (67.6) | 535 (79.9) | <0.001 | 0.94 |

| Provision of materials/patients | 106 (43.6) | 244 (46.2) | 0.75 | 98 (20.9) | 178 (26.6) | 0.05 | 0.29 |

| Obtaining of funding | 39 (16.1) | 114 (21.6) | 0.02 | 66 (14.1) | 134 (20.0) | <0.001 | 0.60 |

| Statistical expertise | 49 (20.2) | 125 (23.7) | 0.24 | 103 (22.0) | 157 (23.4) | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| Administrative, technical and logistic support | 85 (35.0) | 137 (26.0) | 0.02 | 147 (31.3) | 178 (26.6) | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| Collection and assembly of data | 121 (49.8) | 242 (45.8) | 0.05 | 260 (55.4) | 306 (45.7) | 0.008 | 0.90 |

| Final approval of the article | 196 (80.7) | 453 (85.8) | 0.04 | 404 (86.1) | 602 (89.9) | 0.08 | 0.69 |

| Author position, n (%) | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.84 | ||||

| First | 35 (14.4) | 69 (13.1) | 55 (11.7) | 74 (11.0) | |||

| Second | 40 (16.5) | 51 (9.7) | 51 (10.9) | 56 (8.4) | |||

| Middle | 117 (48.1) | 256 (48.5) | 290 (61.8) | 377 (56.3) | |||

| Next-to-last | 29 (11.9) | 70 (13.3) | 40 (8.5) | 77 (11.5) | |||

| Last | 22 (9.0) | 82 (15.5) | 33 (7.0) | 86 (12.8) | |||

*P value testing an interaction between each variable listed and the year in the assessment of gender differences. All p values are obtained from mixed-effects logistic regression models.

Table 3.

Association between female gender and 10 contributions to a research paper by year, univariate (left columns) and multivariable models (right columns) after adjustment for academic degrees

| Contributions | Univariate analysis | Adjusted for degrees | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Conception and design | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.67 | 0.48 to 0.95 | 0.026 | 0.86 | 0.60 to 1.24 | 0.42 |

| 2015 | 0.64 | 0.49 to 0.84 | 0.001 | 0.76 | 0.57 to 1.02 | 0.06 |

| Analysis and interpretation of data | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.95 | 0.64 to 1.39 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.66 to 1.49 | 0.95 |

| 2015 | 0.83 | 0.61 to 1.12 | 0.22 | 0.75 | 0.54 to 1.04 | 0.09 |

| Drafting of the article | ||||||

| 2000 | 1.18 | 0.84 to 1.65 | 0.35 | 1.31 | 0.92 to 1.86 | 0.14 |

| 2015 | 1.07 | 0.82 to 1.39 | 0.61 | 1.16 | 0.88 to 1.52 | 0.30 |

| Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.50 | 0.33 to 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.69 | 0.45 to 1.06 | 0.09 |

| 2015 | 0.51 | 0.38 to 0.70 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.46 to 0.89 | 0.008 |

| Provision of materials/patients | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.94 | 0.64 to 1.37 | 0.75 | 1.57 | 1.03 to 2.40 | 0.04 |

| 2015 | 0.72 | 0.51 to 1.00 | 0.05 | 1.12 | 0.78 to 1.62 | 0.54 |

| Statistical expertise | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.79 | 0.53 to 1.17 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 0.34 to 0.82 | 0.005 |

| 2015 | 0.91 | 0.68 to 1.23 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.42 to 0.83 | 0.002 |

| Obtaining of funding | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.60 | 0.39 to 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.51 to 1.28 | 0.36 |

| 2015 | 0.52 | 0.36 to 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.43 to 0.91 | 0.01 |

| Administrative, technical and logistic support | ||||||

| 2000 | 1.55 | 1.08 to 2.25 | 0.20 | 1.10 | 0.74 to 1.63 | 0.63 |

| 2015 | 1.18 | 0.88 to 1.58 | 0.26 | 1.01 | 0.75 to 1.38 | 0.93 |

| Collection and assembly of data | ||||||

| 2000 | 1.42 | 0.99 to 2.03 | 0.05 | 1.13 | 0.78 to 1.64 | 0.52 |

| 2015 | 1.46 | 1.11 to 1.93 | 0.008 | 1.35 | 1.01 to 1.81 | 0.04 |

| Final approval | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.60 | 0.37 to 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.51 to 1.41 | 0.52 |

| 2015 | 0.69 | 0.45 to 1.04 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.59 to 1.44 | 0.73 |

Association between gender and author position on the byline

Women were more frequently in second position and less frequently in last position compared with men (table 2). Gender differences in author rank did not change over time. After adjustment for author contributions (table 4), the gender difference in last author positions disappeared in both years. Furthermore, women appeared to be more likely to be listed second on the byline (significantly so in 2000) and less likely to be next-to-last (significantly so in 2015).

Table 4.

Association between female gender and position on the byline by year, in univariate analysis (left columns) and after adjustment for research contributions to the project (right columns)

| Author position (vs middle)* | Univariate analysis | Adjusted for contributions | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| First | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.99 | 0.56 to 1.73 | 0.96 | 1.23 | 0.35 to 4.33 | 0.74 |

| 2015 | 1.00 | 0.65 to 1.56 | 0.98 | 1.44 | 0.69 to 3.01 | 0.33 |

| Second | ||||||

| 2000 | 1.55 | 0.89 to 2.72 | 0.12 | 1.94 | 1.05 to 3.59 | 0.03 |

| 2015 | 1.12 | 0.68 to 1.84 | 0.67 | 1.28 | 0.75 to 2.21 | 0.37 |

| Next-to-last | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.63 | 0.34 to 1.17 | 0.14 | 0.73 | 0.39 to 1.36 | 0.33 |

| 2015 | 0.58 | 0.36 to 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.36 to 0.96 | 0.03 |

| Last | ||||||

| 2000 | 0.55 | 0.30 to 1.01 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.32 to 1.98 | 0.62 |

| 2015 | 0.46 | 0.28 to 0.75 | 0.002 | 0.71 | 0.37 to 1.37 | 0.31 |

*36 articles with four or fewer authors were excluded from the analyses.

Discussion

Our main finding is that the contributions to research of women and men authors differ considerably and that these gender roles have remained essentially unchanged between the years 2000 and 2015. At both time periods, women participated less frequently than men in study conception and design, statistical expertise, critical revision of the article and obtaining of funding, but contributed more frequently to collection and assembly of data and to administrative, technical and logistic support. Regarding their place on the article byline, women were less likely to be last authors compared with men, again at both time periods. Nevertheless, the proportion of female authors has increased by 10% between 2000 and 2015. While this reflects progress toward equal gender representation in research, the proportion of women is still well below 50%.

Our study confirmed the trend toward a better representation of women in scientific publications. Under-representation of women in science and in medical fields in particular has been a constant finding over the past several decades.13 This has prompted the launch of national programmes to improve the participation and advancement of women in academic careers.11 The recent increase of female authors in scientific publications may be attributed to these initiatives. Similar to our study, Jagsi et al reported an increase of women with a MD degree among the first and senior authors in six major journals between 1970 and 2004, including the Annals of Internal Medicine.14 Filardo et al described an increase from 28% in 1994 to 38% in 2014 in the proportion of female first authors in six prominent medical journals, also including the Annals of Internal Medicine.15 Improvement in the representation of female first authors was the highest in Europe over the last four decades compared with other regions.16 However, the proportions of female authors reported in scientific publications in the 2000s have remained below 50%. This may be due to women’s preference for clinical and teaching duties over research.17 However, even if this were the case, why women would make such choices is an intriguing question.

An important finding of our study is the gender gap in research roles as captured by author contributions. This confirms the results of Macaluso et al who showed that female authors in the PLoS journals were significantly less likely to be associated with analysis, design, contributing materials or writing of the paper compared with male authors, but that women were more likely to be associated with experimentation.10 We propose here some possible explanations. First, women researchers may be on average younger and less experienced than men. As the increase in the proportion of women in medical sciences is recent, it may be years before women acquire the competencies and acquire the independence leading to more credit and accountability of their research. However, the differences between women and men authors have hardly changed between 2000 and 2015 as we would expect if it was merely a question of catching up. We noted that a larger proportion of female authors had non-terminal degrees and this might explain the higher proportion of non-leadership roles in the research teams. However, once adjusted for the degrees and research topic in the multivariate analyses, we confirmed that the roles in medical research were not the same between female and male authors. Another possibility is that women in science choose different career paths than men, and thus naturally take on different tasks (if so, why this should be the case would deserve exploration).18 Finally, it is possible that the task differentiation reflects to some extent sexist attitudes that are prevalent in society—to caricature, women take care of various chores while men discuss lofty ideas in the smoking room. Some authors have argued that women may have a different self-perception of the tasks they should accomplish or not and may be less reluctant to perform administrative, technical or logistical tasks compared with their male counterparts.19

The author’s position on the article byline depends on cumulative contributions and the type of tasks performed in the research project as well as seniority and responsibilities in the overall work.20 We observed that women were less likely than men to be last authors compared with middle author positions. In their study, Jagsi et al reported an increase in the proportion of women at last positions in scientific papers over a 30-year period.14 As the position on the article byline likely depends on contributions to specific tasks, we adjusted our models on this variable and this masked the association between gender and senior author position. This finding suggests that the contribution to specific roles in the research project is key for achieving a prestigious position among authors.

This study has strengths and limitations. The originality of our study relies on the comparison of contributions reported in a standardised manner 15 years apart. Originally, we intended to include a sample of journals. However, we found out that most journals do not record author contributions in a consistent way over time, unlike the Annals of Internal Medicine, and this forced us to restrict our research to this single journal. However, restriction to a single journal may limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, the 10 contributions to research were self-reported and not verified by the study investigators. A previous study suggested that descriptions of contributions may lack reliability because they are frequently completed by the corresponding author of the paper.21 Whether such errors may have biased the comparison of female and male authors is unclear. Third, we cannot totally exclude misclassification of some authors’ gender. However, we used methods that were previously reported and assessed and believe that such errors should be rare.14 15 Finally, we did not obtain information on the authors’ age, past experience in research, professorial rank, medical specialty and primary scientific discipline, which may all contribute to gender differences in specific research roles (figure 1). Therefore, our ability to explain causes of gender differences remains limited.

Our results highlight that research roles are not distributed equally between women and men researchers and that these differences have remained unchanged over a 15-year period. This may be due to justifiable reasons, such as seniority, specific training and skills in research, or role preferences of the researchers. However, the possibility also exists that the academic research milieu perpetuates sexist attitudes and unequal treatment of researchers based solely on their gender. This issue requires further exploration, and justifies the continuation of local initiatives (such as gender equality commissions in universities, or mentoring programmes) that promote women’s involvement in research and ensure fair career opportunities, regardless of gender.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rosemary Sudan for editorial assistance of the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: AG-A participated in the conception & design; analysis & interpretation of data and she performed the statistical analyses. She contributed to the provision of study materials, collection & assembly of data, and she also provided administrative, technical, or logistic support. She drafted the first version of the manuscript and participated to the critical revision of it for important intellectual content. She has approved final version of the article. AP, TP participated in the conception & design; analysis & interpretation of data. They contributed to the provision of study materials, collection & assembly of data and also to administrative, technical, or logistic support. They participated to the critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. They have approved final version of the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No unrestricted data sharing at this time. Interested parties may contact the corresponding author to gain access to the dataset.

References

- 1. Burton KR, Wong IK. A force to contend with: The gender gap closes in Canadian medical schools. CMAJ 2004;170:1385–6. 10.1503/cmaj.1040354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2006-2007. JAMA 2007;298:1071–7. 10.1001/jama.298.9.1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levinson W, Lurie N. When most doctors are women: what lies ahead?. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:471–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillips SP. The growing number of female physicians: meanings, values, and outcomes. Isr J Health Policy Res 2013;2:47 10.1186/2045-4015-2-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramakrishnan A, Sambuco D, Jagsi R. Women’s participation in the medical profession: insights from experiences in Japan, Scandinavia, Russia, and Eastern Europe. J Womens Health 2014;23:927–34. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G. Career choices of United Kingdom medical graduates of 1999 and 2000: questionnaire surveys. BMJ 2003;326:194–5. 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, et al. . Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:16474–9. 10.1073/pnas.1211286109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1103–15. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, et al. . Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:804–11. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Macaluso B, Larivière V, Sugimoto T, et al. . Is science built on the shoulders of women? A study of gender differences in contributorship. Acad Med 2016;91:1136–42. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ADVANCE: Increasing the Participation and Advancement of Women in Academic Science and Engineering Careers (ADVANCE). https://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=5383 (Accessed on 9 May 2017).

- 12. Perneger TV, Poncet A, Carpentier M, et al. . Thinker, Soldier, Scribe: cross-sectional study of researchers’ roles and author order in the Annals of Internal Medicine . BMJ Open 2017;7:e013898 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Handelsman J, Cantor N, Carnes M, et al. . Careers in science. More women in science. Science 2005;309:1190–1. 10.1126/science.1113252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jagsi R, Guancial EA, Worobey CC, et al. . The “gender gap” in authorship of academic medical literature-- a 35-year perspective. N Engl J Med 2006;355:281–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa053910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Filardo G, da Graca B, Sass DM, et al. . Trends and comparison of femal first authorship in high impact medical journals: observational study (1994-2014). BMJ 2016;352:847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wininger AE, Fischer JP, Likine EF, et al. . Bibliometric Analysis of Female Authorship Trends and Collaboration Dynamics Over JBMR’s 30-Year History. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:2405–14. 10.1002/jbmr.3232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amrein K, Langmann A, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, et al. . Women underrepresented on editorial boards of 60 major medical journals. Gend Med 2011;8:378–87. 10.1016/j.genm.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sidhu R, Rajashekhar P, Lavin VL, et al. . The gender imbalance in academic medicine: a study of female authorship in the United Kingdom. J R Soc Med 2009;102:337–42. 10.1258/jrsm.2009.080378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rudman LA. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: the costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:629–45. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zbar A, Frank E. Significance of authorship position: an open-ended international assessment. Am J Med Sci 2011;341:106–9. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181f683a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ilakovac V, Fister K, Marusic M, et al. . Reliability of disclosure forms of authors’ contributions. CMAJ 2007;176:41–6. 10.1503/cmaj.060687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.